David Horvitz

Do you have to be a visionary to imagine such an endeavour to turn off the city lights?

Eridanus, the project which led David Horvitz to Paris in 2017, echoed the proposal made by Italo Calvino who, in Invisible Cities, projected the sky’sconstellations over Andria, one of the invisible cities.1 After selecting thirty lampposts in order to reproduce the design of the Eridanus constellation, the artist obtained their keys and quite simply turned them off, thereby producing a negative double of the starry river which illuminates the night sky in the southern hemisphere. Needless to say, a thoroughly poetic dimension came into that project, which mixes countless possible resonances, like those which poets have with the stars, a source of daydreaming and contemplative rapture in the face of the infinite. If that piece can be conceived as an extension of the psychogeographical peregrinations of the Situationists, it also focused the gaze on more worrying contemporary phenomena. As Stefanie Hessler observes in an interview with the artist2: “We have all been robbed. Losing layers and layers of air. The sky above us has lost its depth, depriving us of glimpse of infinite perspective”. David Horvitz’s project was conceived on the basis of reports gathered among Parisians who “lamented that the stars can no longer be seen at night ever since the installation of public lighting”. Not that we should take this de-installation to be a literal ecological plea, but rather, in addition to the consequences of global warming and other forms of pollution implicit in the thoughtless illumination of our cities, that we should envisage the lost possibility of grasping the infinite with the naked eye, with no technological go-betweens, as 20th century city-dwellers were still able to do, without having to travel thousands of miles to be in deserts as far-flung as the Atacama Desert in Chile.

One of the possible ways of reading David Horvitz’s work is to understand it as a poetics of resistance to a whole host of dramatic consequences due to the speeding-up of the pace of our civilization and the exponential growth of our capacity to produce consumer “goods”. One of the works on view at La Criée in Rennes, Nostalgia, is quite akin to Eridanus, if not form-wise, then at least project-wise: in Nostalgia, the artist proposes getting rid of the thousands of photos he accumulates during his wanderings, mainly from beside the sea which he is especially fond of. The digitized photographs are thus projected one last time before being irrevocably destroyed. In this nothing if not romantic process, whose title clearly displays the psychological atmosphere in which it occurs, Horvitz tacks once again against the current of a history—ours—which tends rather to encourage the endless storage of visuals of every sort, reflecting an exaggerated accumulative reflex. In this sense, the artist’s sacrificial gesture is considerably more effective in its self-destructive symbolism than many a critical discourse about the compulsive consumerism of imagery in our day and age, and the anguish about loss that goes hand-in-hand with it.

Here again, however, it would not be fair to reduce Horvitz’s work to a gesture of resistance to or awareness of the various societal and climatic phenomena threatening us. The key work in the show, Lullaby for a landscape, fills the art centre’s main room and consists in the elliptical alignment of a series of chimes hanging from the beams. Each wrought brass bell produces a unique sound which calls for handling one of the pieces of flotsam available to the public, these sticks having been brought back from one of the many Breton beaches that the artist walked along while preparing the exhibition. Going round these acoustic cylinders, and moving them one after the other in the right direction is tantamount to performing the tune of the Breton lullaby. In this instance, it is not a matter of paying some demagogic tribute to a local public, but rather of paying real attention to the traditions and languages of host territories. This attention is also clearly visible in a recurrent piece produced by the artist, Proposals for Clocks, for which he has translated into Breton one of the usual statements, as he also systematically does into the language of the region in which the art centre or gallery showing his work is located: a gesture of acknowledgement, homage to a popular tradition by a Californian artist keen to respect minority cultures. Lullaby for a landscape is disconcertingly simple, which likens it at first glance to a minimalist or serial gesture, before the irregularity of the chiming tubes and the informal look of the accompanying sticks dispel that initial feeling. There subsequently emerges an impression of finding yourself inside a huge organ which it is possible to “play” from within. Visitors are incidentally offered a free hand to make these instruments vibrate, without respecting the direction they move in, which, alone, makes it possible to produce the melody. On the other hand, the merry cacophony that comes from these monotubes struck by inexpert hands seems to thoroughly suit the artist, who has clearly produced a work intended for the public, who are, for once, invited to take it out on it.

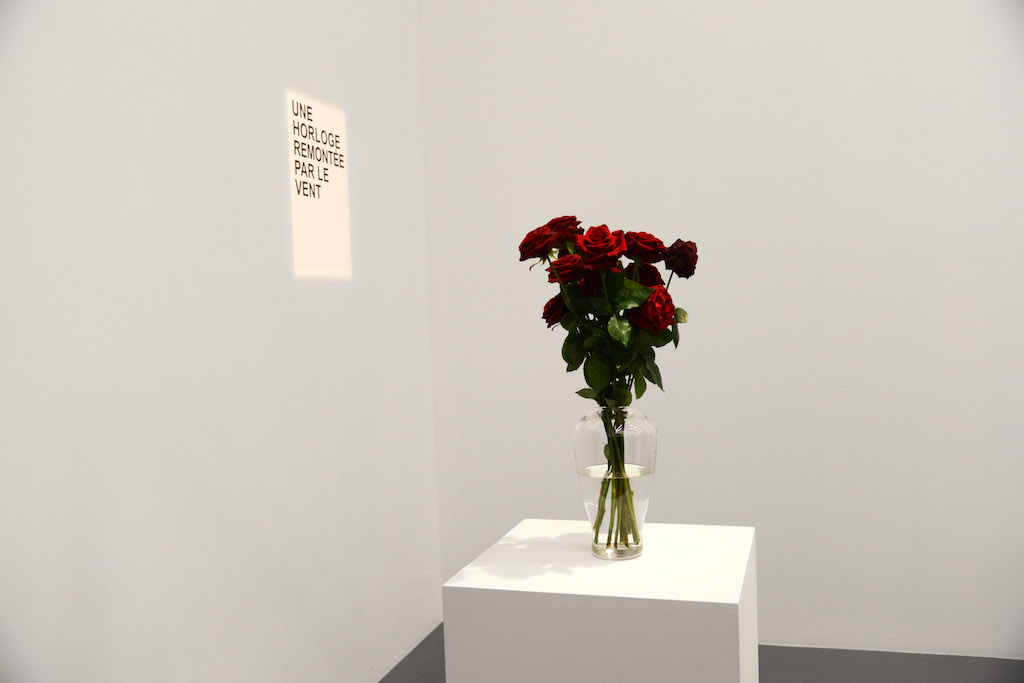

The Proposals for Clocks installed inside La Criée, but also scattered throughout the city on municipal hoardings, ring out with one of the artist’s ongoing concerns with the matter of time. Here, his proposals appear in the form of poetic declarations whose meaning seems bent on thwarting the relentless logic of time passing: we find once again the romanticism already at work in Nostalgia, but, precisely where the artist preferred to destroy the traces of time’s flow, here the “vanitas” is displayed in a radically different way, as if cocking a snook at the inexorable. These joyous and deliberately anachronistic statements, like this “clock asleep on its feet”, seem to want to both ward off and foil the passage of time, as if what were involved was a huge joke. This relation to time’s flow may well pass through more disorienting positions, like wanting to open an exhibition at the moment when your daughter is born…3 This quest also links up with some of the artist’s other recurrent preoccupations, like those to do with going beyond the brutal mechanical nature of time-measuring instruments, in order to connect with oceanic rhythms, with the nature from which we have come, but which we find it harder and harder to refind, and even with the cosmos, as suggested by Eridanus.

David Horvitz’s nomadism can be translated in various ways, and it corroborates this liking for the immaterial and the ephemeral which hallmarks his work: a few years ago, he posted on Wikipedia a series of pictures of him taken on a beach to illustrate the article Mood Disorder. Those pictures, which are not copyrighted, like all Wikipedia images, found themselves freely surfing the Internet. The artist explains that he did not try to get them to circulate, but that they did so all on their own: Margot Norton, interviewing him, is fond of comparing them to seeds carried along by the wind which will sow other territories.4 At La Criée, he has re-used a piece which he likes reenacting, involving a floral cartography consisting in a regularly renewed bouquet made up of the same flowers picked the same day, but in different places he is especially fond of (Map of Brittany from a Wednesday); in Venice he is planning to set up guided visits in the footsteps of Stravinsky when he visited the City of Doges, which is now his resting-place, proposing to Biennale visitors and mere strollers to momentarily catch their attention by offering them impromptu concerts (3 Easy Pieces). So Horvitz’s nomadism is above all a nomadism of dispersal, or even of disappearance, like those posters scattered throughout the city of Rennes and doomed to be inexorably erased by bad weather. There is something of an abandonment and a letting-go in his work which perfectly matches a renewed relation to the vanitas, a vanitas that is not melancholic, a vanitas which, like all forms of vanitas, certainly puts our endeavours down here on earth into perspective, but which, in this case, is rather trying to withstand the asphyxia caused by the thousands of artefacts that are inundating us, the stupefying effect of futile gesticulations, and the bedazzlement of the light from the street lamps which deprives us of being able to contemplate night skies.

1 Italo Calvino, Les villes invisibles (Le citta invisibili), Andria, p. 180, 2013, Folio Gallimard for the French translation.

2 David Horvitz, Eridanus, 2018, Los Angeles, Steck, texts by: Stefanie Hessler, David Horvitz, Lucy Hunter, Alexandra Pedley.

3 The opening of the two simultaneous exhibitions at Jan Mot’s and Dawid Radziszewski’s galleries was in fact dictated by the birth of his daughter, a matter, he says, “of complicating gallery schedules by taking his girlfriend’s biological (and lunar) rhythms into account…”

4 Conversation between David Horvitz and Margot Norton, Cura, n°26, Oct. 2017.

3 Easy Pieces, Venice Biennale, different venues, May 2019

The Shape of a Wave Inside of a Wave, La Criée, Rennes, 19.01–10.03.2019

Metaphoria III, le 104, Paris, 6.10–11.11.2018

Image on top: David Horvitz, Proposals for Clocks, 2016-2019. Posters in French and Breton displayed across the city. Production : La Criée centre d’art contemporain, Rennes. Courtesy David Horvitz ; ChertLüdde, Berlin ; Yvon Lambert Libraire & Éditeur. Photo : Benoît Mauras.

- From the issue: 89

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Jack Warne, Alun Williams, Ben Thorp Brown, Mircea Cantor, Olivier Mosset, Jean-Baptiste Sauvage,

Related articles

Julien Creuzet

by Andréanne Béguin

Anne Le Troter

by Camille Velluet

Sean Scully

by Vanessa Morisset