Jack Warne

Sound waves from a surround sound system fill the ICA’s concert hall as the audience finds itself immersed in semi-darkness; meanwhile, the performer has just dived underneath a pile of threadbare carpets, where he will stay hidden during the entire concert in order to stay “connected” to his “turntables”. Layers of sound unfurl themselves over the course of 45 minutes, alternating between techno beats and sung passages, noise, sudden explosions and light ambient passages, which appear briefly in order to release us from the grip of excessive sound swirling above our heads. 36 speakers are installed in the ceiling of the London art centre—the source of this apocalypse of sound. As the audience leaves the concert hall, still a bit dizzy from the immersive and total experience which leaves no respite for our eardrums nor for our imagination, we are caught up in this polyphonic net which takes us on a tour of a multitude of musical horizons, reflecting street scenes where background noises evaporate, far-away storms rumble, pickaxes drill into our ears, all of this punctuated by lively conversation.

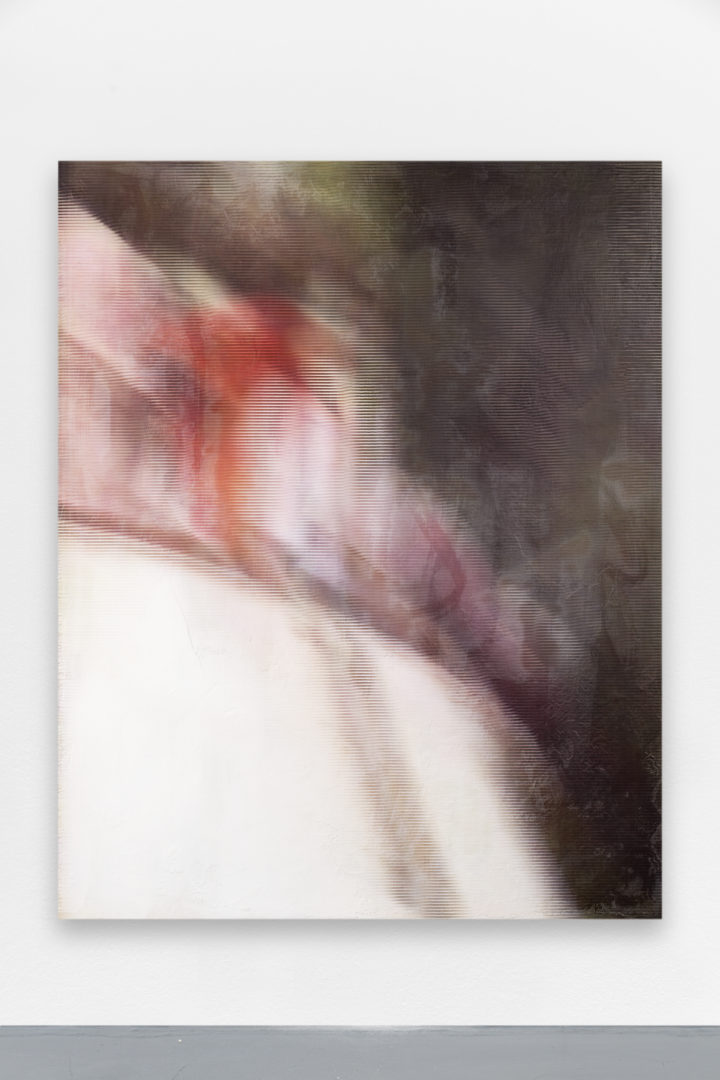

The performance the audience has just seen in this temple for contemporary art and music that is the ICA—the beating heart of a London scene which has witnessed many experimental scenes over the years—is a first for Gaunt, Jack Warne’s stage name. Earlier that afternoon, we were given a tour of the billboards bearing the young artist’ flamboyant paintings in which silhouettes can vaguely be discerned beneath colour fields, in an effort to create an effect which was used in all of the images belonging to this series of sign paintings.

Back in the East End, a new series of Jack’s works was on display, similar to those which were shown at the Spiaggia Libera gallery in Paris. The London space was located in a concrete bunker which was chosen especially for the purpose of providing a backdrop for the artist’s work by the two curators of the show. The drip marks made from the concrete as it dried dialogued nicely with the incidental surface markings of the artist’s paintings. In one corner of the gallery, a cluster of vaguely anthropomorphic speakers hung from the ceiling, emitting sounds which were not unfamiliar. On the wall here and there hung sheets of paper yellowed by time which offered only the faintest glimpse of indecipherable scribbles on the reverse, while on the right side QR codes could clearly be seen which everyone scrambled to scan. This allowed us to go deeper into Jack Warne’s universe, where our perception of the object-painting—residing as ever, on a surface level—represents only the first stage in a voyage of the senses which goes far beyond our usual way of experiencing a painting, enriching as this already may be.

The title gives us an inkling of what to expect from this exhibition; “Blind at The Age of Four” is not a mere poetic or esoteric formulation, it references the artist’s childhood and the illness which afflicted him at a very early age, leaving him partially blind and causing him to develop a particularly well-honed sense of hearing, as well as a sensibility geared toward music. This rare condition also caused him to become hyper-attuned to relationships with his family members and the “family music” which he never lost track of while studying art, at which point his eyesight was restored. Once connected to the Wi-Fi at the gallery, smartphone in hand, the visitor has only to aim the captor at the paintings in order to see them miraculously spring to life and play short Instagram videos from the artist’s page which “augment the reality” of the paintings. This converts them into a window beyond their mere surface, crashing through this layer in order to transport the viewer to a head-spinning dimension of visual sensations and sounds. The source of the videos are photographs and films made at a time whilst the artist was still in the grips of his illness. Although not particularly evident, these images are charged with emotion. The colours seem to dance to the music, adding to the potential levels of interpretation and aesthetic approaches these augmented paintings conjure.

Something somehow magical and unprecedented happens through this technological manipulation—it also seems perfectly logical given the digital technology available to us, which has gained access to all areas of our consciousness as well as our existence in the world, with even our emotions becoming monetized. With the involvement of artificial intelligence in every debate concerning the possible dispossession of what lies at the heart of humanity these days, along with its capacity to invent counter-narratives which resist the homogenisation of technology, Jack Warne’s use of this technology seems to reconcile us with the latest available tools. For Anna Longo, who recently wrote Le jeu de l’induction. Automatisation de la connaissance et réflexion philosophique (The Induction Game: The Automation of Knowledge and Philosophical Thinking), artists and philosophers are the only ones able to provide us with alternatives to the funnelling effect AI has on us, leading us to exclusively utilitarian and commercial ends.

Faced with this rupture, the question we can legitimately pose is the following: what does augmented reality add to our “usual” perception of a painting? It is worth noting that Jack Warne’s practice is already physically “augmented”, since it is the product of a multitude of techniques which are updated within an object-palimpsest which can consist of up to five different layers. The aluminium frame, covered in either moss or carpet depending on the project, is covered in a layer of plaster in which a piece of curtain is buried, before the ensemble becomes a supporting structure for a U.V. print produced by the artist using experimental methods. Perhaps someday he may add real touches of acrylic paint, as the artist does not have anything against a painter’s canonical gesture. The presence of the curtain, with its loud motifs, is of prime importance for the artist, who makes a particular effort to include vernacular elements in his works. These fragments of everyday life, just like the worn carpets which made up the “flying carpet” which hid him from the audience’s view or the yellowing sheets of paper bearing scribbles and printed QR codes. Jack Warne’s inclusion of curtains in his paintings adds an almost Proustian dimension to his works, they are a memorable and thus emotional occurrence…

Jack Warne’s work can only be seen from the perspective of a world in which digital technology is widespread and AI becomes just one more tool, and not an end in and of itself. Also, can we not compare it to the paintbrush strokes the artist has chosen to embrace? The notion of the avatar—which the artist produces via technology—becomes a vector between the visual arts world and the music world, both of which he participates in actively. Gaunt is more than just a stage moniker, it is also a digital phantom which takes on the form of a medieval suit of armour which ranges from stage costume to symbolic and metaphorical protection which references the fragility of a childhood impacted by impairment and the dangers of a double exposure when on stage. Gaunt is also the symbol of an identity which is more and more often defined virtually, divorced from its corporeality, a spectral doppelgänger the artists sends out to scout the limbo of virtual reality. Coming from the land of Shakespeare, somehow it makes sense…In Paris, the artist references the Elizabethan, whom he “asks” to compose a new sonnet via ChatGPT. Literary treason, ultimate taboo—to disturb the most illustrious literary and poetic figure—or attempt to resuscitate his poetry?

1 “Alors, je ferme les yeux”, Spiaggia Libera gallery, Paris, 7.6 – 29.7.2023

2 Eva Illouz (dir.), Les marchandises émotionnelles. L’authenticité au temps du capitalisme, Paris, Premier Parallèle, coll. « Collection générale », 2019.

3 Anna Longo, Le jeu de l’induction. Automatisation de la connaissance et réflexion philosophique, Sesto San Giovanni, Éditions Mimésis, coll. « Art, esthétique, philosophie » ; 2022 ; cf. See interview with the writer by Clémence Agnez in the current issue of 02.

______________________________________________________________________________

Head image : Jack Warne’s Billboards, London, 2023. Courtesy of DIABOLICAL part of BUILDHOLLYWOOD.

- From the issue: 104

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Tohé Commaret, Alun Williams, Ben Thorp Brown, Mircea Cantor, David Horvitz,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset