Tohé Commaret

« Vous voyez, le temps que vous pouvez passer dans le passé commence au moment où Kazu a versé votre café et se termine juste avant que le café ne refroidisse. La raison la plus courante de vouloir retourner dans le passé est de refaire quelque chose. Mais comme rien de ce que vous faites dans le passé ne peut changer le présent, tout le monde a envie de dire “alors, à quoi bon revenir en arrière ?” »

Toshikazu Kawaguchi, Before we forget kindness. Série Before the coffee gets cold, Picador Books, 2023.

For the first time in her young career, Tohé Commaret (born in 1992) has created a joint work with her brother Grichka as part of their duoshow ‘Miss Recuerdo’ at the Fondation Ricard.

The video Palma (2025) captures, with a few differences that only a trained eye can discern, most of the codes and atmospheres described by the young filmmaker: first, the setting of a Parisian suburb, which both of them know perfectly well having grown up there; second, a particular focus on the young women who live in this suburb and who feature in most of the videographer’s latest films; and finally, a form of light fantasy that seeks to break free from an overly burdensome everyday life that the possibility of a magical re-enchantment would lighten. At the Fondation Ricard, Grichka Commaret’s minimalist black and white paintings respond to the video artist’s tight shots of mustard-coloured corridors and cosy interiors, while the inventive scenography of the duo CluelesS multiplies unexpected points of view and disrupts our habits of film viewing.

My Hood Will Not Be Brought Down

Most of Tohé Commaret’s films are set in the suburbs near Paris, in the Vitry-sur-Seine estate where the artist grew up and which she continues to explore. Her view of its architecture, its streets, its passageways and the land that was once called ‘wastelands’ is completely renewed; she no longer lingers to lament the dilapidation of neighbourhoods ravaged by the abandonment of institutions and municipalities. Tohé Commaret’s suburbs are far from glamorous, but it no longer gives off that sordid impression that we used to see all the time in films shot there, with its lots of tags and graffiti ‘decorating’ stairwells filled with rubbish, car parks where stripped cars lie in the middle of various debris. The architecture of this suburb is barren, without any particular aesthetic quality; you pass through it without even glancing at it. Tohé Commaret’s camera lingers on deserted corridors before alternating with scenes of groups of young people hanging out, girls with girls and boys with boys. The genders rarely mix. The long scooter rides in the film 8 (2022) take them along deserted streets where the façades follow one after the other and all look the same, before opening out onto playgrounds full of busy children. For young women, life is often elsewhere, in the interiors of these buildings where they meet up to share their love stories, their strategies for finding a partner or simply to invent better futures for themselves in order to escape the torpor that seems to have seized these suburban dwellers. As for the young men, they tend to be outside, confirming a sociology of the suburbs that we thought had evolved differently. In the opening shot of the film 8, a young man in the midst of his friends proclaims his vital need for money (‘money!’), a radical and definitive slogan, thus describing a real obsession that says a lot about the imperatives of life and the implacable realism of a population of young suburban adults.

Still shots and sequence shots

The director is not a fan of tracking shots or complicated movements; she prefers extended still shots, sequence shots that can even last the entire film, as in Chips (2020), where the heroine seems to have forgotten the presence of the camera. However, it is not a question of acting as if it does not exist: her actresses are more than aware of the presence of the camera, constantly looking at it, sometimes even staring at it resolutely. The cinematographic model, in which the aim was above all to ignore the lens in order to accredit the idea of fiction, seems to be a thing of the past. In fact, Tohé Commaret’s videos are closer to documentaries, even though the video artist does not claim any ethnographic position. Her films are not scripted: floating and syncopated, they are populated by parallel narratives with no apparent connection to the main one, but always end up ‘scripturally landing on their feet’. The director achieves a subtle balance between improvisation and ‘directing actresses’ that gives the impression of letting go or rather of a non-authoritarian, non-hierarchical production. Hence the feeling that these screenplays are the result of a collective project, of co-authorship. The uninhibited play of the ‘actresses’ reflects a real mastery of image and shooting, symptomatic of an era in which young people have appropriated the camera tool through the use of smartphones and Instagram or Tik Tok videos, which have formed a spontaneous generation of actors and directors. While the camera movements are sometimes simple, even static, the complexity lies more in the scenarios, which are endlessly complicated, where one gets lost in the narrative mazes, in the untimely jumps from one register to another, with no narrative coherence at first glance, except that in the background, it is always about filming the suburbs and their inhabitants, their micro-dramas and their vanished hopes.

Horizontality

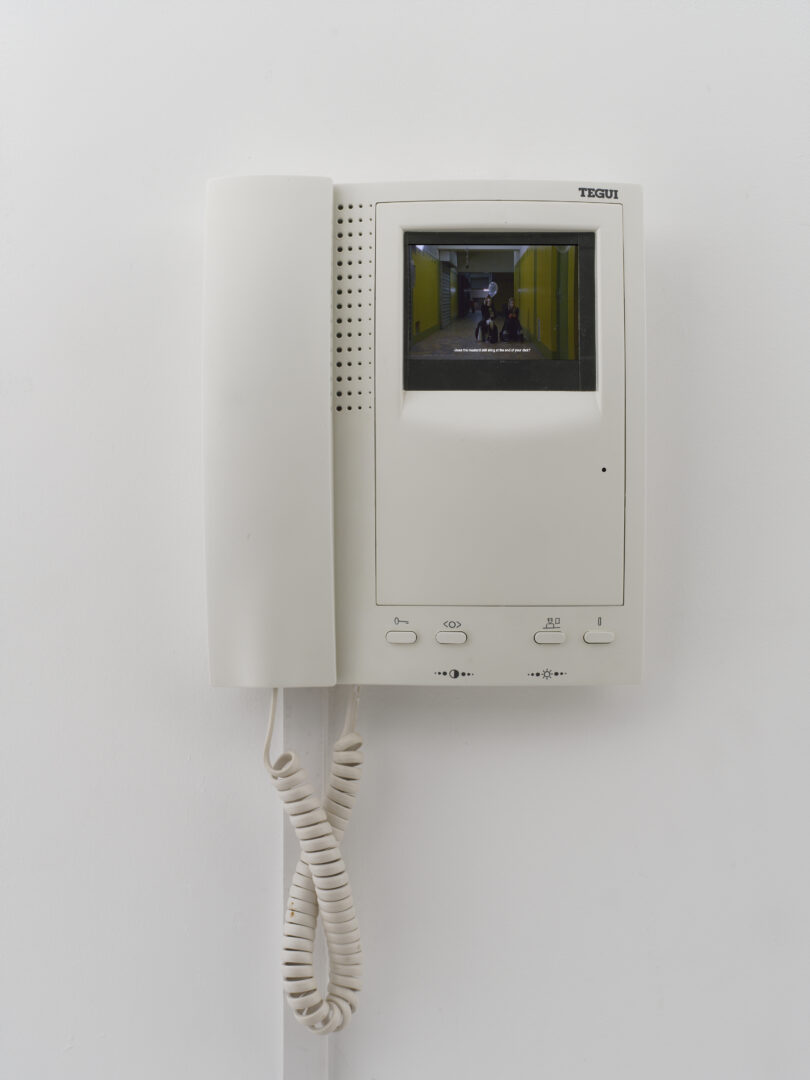

Tohé Commaret is on the same level of social belonging as his ‘actresses’. The overbearing relationship that can exist between the director of a film and his or her actors disappears in a horizontality that is evident at all levels of the production: in the ‘letting it be filmed’ aspect of directing, in what appears to be constant improvisation, but also in the dialogues and language borrowed from the daily lives of her actresses. Mustard (Interphone) (2023), cleverly presented on the screen of an intercom that gives it its title, unfolds a scene that is comical to say the least, with more than risqué exchanges between the young women and the ‘target’ of their sarcasm, a naive young man who willingly submits to the crudeness of their mockery and to a totally assumed verbal sadism. The language is that of youth, of a suburb where slang language (suburban argot that ends up infiltrating all strata of society) is mixed with more vernacular speech. The various passages in 8 give us fairly clear insights into this colourful, whirling language, where verbal tics such as the word ‘genre’ that punctuates all the heroine’s sentences sometimes take on the appearance of an ultra-expressive pidgin that expresses both the radicality and the subtlety of real situations.

Stories of young women

Tohé Commaret mainly films young women who resemble her in their dress code, their way of speaking, etc.; there is a very close relationship, a deliberate absence of distance with his ‘actresses’ who seem to play no other roles than their own. There is therefore no composition, but rather an extension of scenes from their daily lives that they transport in front of the ‘lens’ of a camera that is more domestic than intrusive, which has become more of a banal than exceptional object that would intimidate them. The young women filmed by Tohé Commaret are often confronted with the violence or indifference of their partner: in Because of (U) (2024), the heroine finds herself being picked on by her partner, who is complaining about a billion things. She remains silent in the face of a flood of words that she does not even try to counter, already tired by impossible justifications that she knows from the outset are inaudible, grappling with recurrent reproaches; in the long static shot that lasts almost half the film, the female character gives the impression of living eternally in a situation that seems unlikely to change. A weariness emanates from the characters, stemming from a mixture of incomprehension and astonishment in the face of behaviours and attitudes that are the product of a paternalism from another age and which appear to be profoundly out of step with their obvious adaptation to the pitfalls of everyday life, which they seem for the most part to face head-on. In this context, the apartment is more than ever the refuge where the friends meet, the words are free, the censorship disappears, the laughter explodes and all the fantasies are allowed. Situational inventiveness is given free rein, as in 8, where the young woman gives a long monologue on the effect of the green laser and the idea of ‘eating the light’, which she literally performs live. The artist’s favoured setting is, in fact, the closed space, a setting that can be as easily the semi-open space of a corridor (Mustard) as the more conventional spaces of a bedroom (Chips) or the living room of an apartment (8).

The magical escape

In Tohé Commaret’s films, daydreaming is seen as an antidote to the heaviness of everyday life. This search for a magical escape is a recurring theme, found in the actions of children who cling to it stubbornly (Pukyu) or in those of young adults who see it as a way of overcoming an unsatisfactory everyday life, incapable of arousing any form of investment in an emancipatory future: In Palma, the intrusion of an extraordinary invention by a Japanese surgeon who, by micro-incisions in the lines of the hand and by redrawing their path, transforms the future of his patients, is reminiscent of cosmetic recipes that promise women to boost their potential for seduction via various cosmetic stratagems. A magical thought to which the young heroine of the film surrenders herself, just like the little girl in Pukyu who refuses to give up on the story of a fontanelle that never closed, which would allow spirits to communicate with each other, a kind of natural telepathy from Quechua legends… Each time, the dream is shattered by adult realism, the child’s mother in Pukyu, the heroine’s girlfriend in Palma, who appears much more committed to a logic of normality with a job that nevertheless seems to bring her only meagre subsidies and an insistence on pushing her friend to take care of her hair in order to give her an appearance more in line with what society is supposed to expect from a young woman looking for a job.

Has the spirit of rebellion left the suburbs?

Tohé Commaret’s films paint a mixed picture of a suburb where past emancipatory impulses seem to have been ground down by the mill of disillusionment, the only escape from the heaviness of a disenchanted everyday life being to escape through daydreaming or belief in miraculous solutions. However, the light-hearted fantasy atmosphere that she brings to most of her films tempers this heaviness, just as the young women’s freedom of speech and their caustic humour loosen a situational vice that seems unlikely to open any time soon.

Head image : Tohé Commaret, Because of (u), 2024. Film 10 min, extrait du film / extract from the film.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Jack Warne, Alun Williams, Ben Thorp Brown, Mircea Cantor, David Horvitz,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset