The Story That Never Ends

The Story That Never Ends, The ZKM Collection

5 avril – 20 août 2025

ZKM, Karlsruhe

The ZKM, Zentrum für Kunst und Medien (Centre for Art and Media) in Karlsruhe has been a key venue on the German and European art scene for over thirty years, occupying the multifaceted field of digital arts research, conservation, restoration and exhibition. At a time when digital technologies are becoming increasingly important in contemporary creation – but also more broadly in everyday life – the ZKM’s perspective on the challenges of these cutting-edge technologies and their relationship to our weltanschauung, to use a German term that is particularly appropriate in this context, takes on its full significance. ‘The Story That Never Ends. The ZKM Collection’ is a retrospective look at a collection that has been built up over the past thirty years, featuring works from the 1950s to the present day and highlighting iconic works that have rarely been shown due to their fragility or because they required extensive restoration work, such as gems like Yoko Ono’s performance videos or Rebecca Horn’s extraordinary piece (Memorial Promenade, 1990); works that are as much markers of technological advances (the intrusion of portable video or the automation of systems) as they are of behavioural and political changes in our societies.

Objet cybernétique ; bois, verre acrylique, moteurs, composants électroniques, lampes à incandescence, amplificateur (aujourd’hui : mixeur), tourne-disque (aujourd’hui : lecteur multimédia numérique), microphone / Cybernetic object; wood, acrylic glass, motors, electronics, incandescent lamps, amplifier (today: mixer), record player (today: digital media player), microphone.

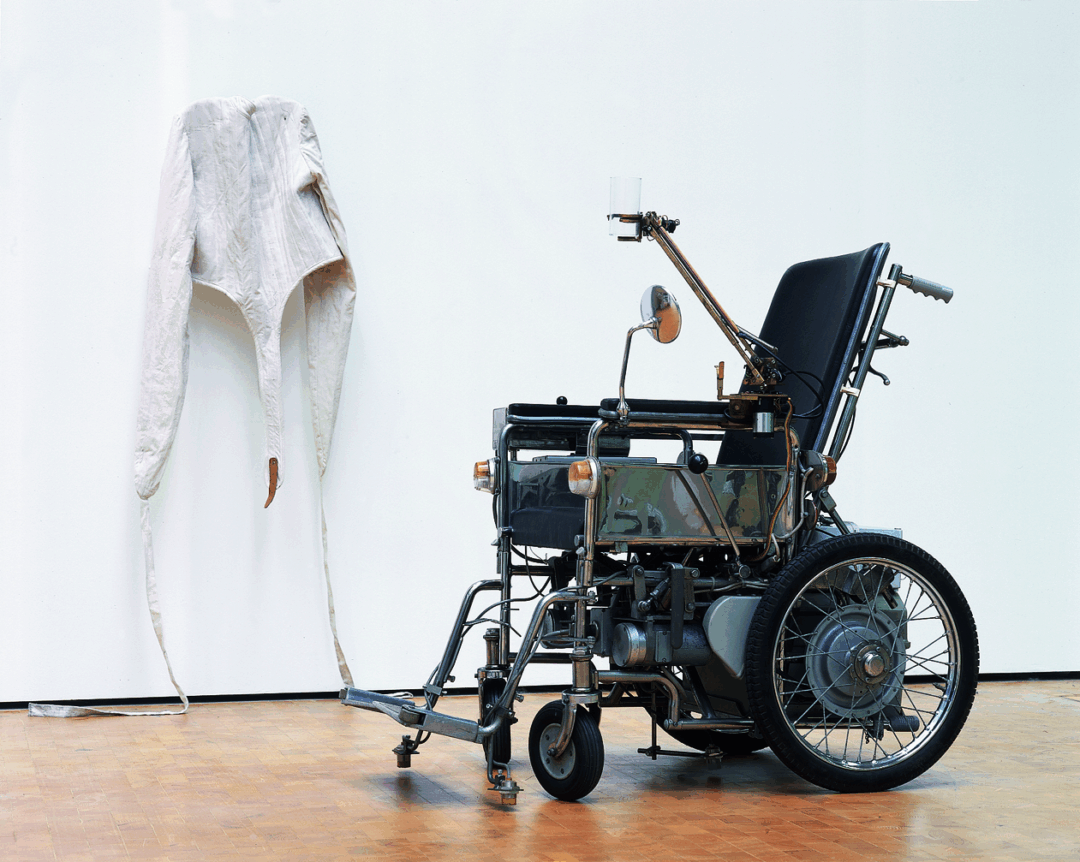

The ZKM is a unique structure, neither quite a museum, nor quite a collection, nor just a school or research and restoration centre. It brings together all these orientations in an organic structure carefully maintained by the curators who have succeeded one another at its helm. The latest director, Alistair Hudson, is no exception to this rule, which seeks above all to place art at the heart of societal questions: ‘The Story That Never Ends. The ZKM Collection’ can be understood as a fresco that begins in the mid-20th century and ends with the latest works created using artificial intelligence. One thing is clear: between the piece by French pioneer Edmond Couchot (Sémaphora III, 1960), with its incredible tangle of wires hidden behind a makeshift panel where coloured bulbs and neon tubes light up alternately, giving the whole thing an incredibly rudimentary appearance, and the work by Hanna Haaslahti (Captured, 2019-2022), which reacts almost in real time to the approach of viewers, incorporating them into the video that self-generates before their eyes, we have the impression of a fantastic rupture that testifies to a spectacular acceleration in technological progress. But this impressive leap also makes us aware of the loss of the ‘readability’ of tools and the now extreme opacity of their functioning and understanding. This observation is not foreign to the field of experimentation and research that the ZKM pursues within its structure, which consists of recording and analysing the risks that this dispossession of tools poses to users, i.e. to ourselves. Beyond all these philosophical and societal concerns, with which the ZKM’s management team has strong ties, originating in the contributions of seminal philosophers such as Gilbert Simondon, Bernard Stiegler and, closer to home, Yuk Hui, the exhibition presented at the ZKM manages to escape this imposed ‘subject’ of art’s increasing dependence on digital technologies and the possible influence it may exert in return on the latter in terms of awareness, offering us a particularly enjoyable journey, where iconic works follow one another in spectacular fashion. The first example is Bill Viola’s Stations (1994): in this canonical work, the American artist develops one of his favourite themes, that of the meaning of existence, the feeling of floating that we can experience at times when faced with the mystery of destiny, transposing it “literally” by displaying four video tableaux in which submerged bodies appear lifeless, floating in what could symbolise foetal life in amniotic fluid, in a highly symbolic shortcut. An entire room, plunged into darkness as it should be, has been dedicated to this major work by Viola. In the centre of the large hall, a circle delimits a space in which a wheelchair waits to be activated: this is the work by Rebecca Horn mentioned above, also highly symbolic of a condensed vision of existence, which is eloquent to say the least… This first part of the work is complemented by its counterpart, a gaunt mannequin that comes to life at times, triggering the movement of the wheelchair within the circle that delimits its path. Earlier, we were delighted to discover Paul Garrin’s legendary installation, Yuppie Ghetto with Watchdog (1989), undoubtedly one of the first ‘interactive’ works in history, in which the viewer’s approach to the screen triggers increasingly loud barking from a dog whose mouth becomes more and more threatening; This work also used one of the first computers to be integrated into a video installation. Marie-Jo Lafontaine’s monumental installation, Les Larmes d’acier (1987), is another example that deconstructs the figure of the heterosexual male in all his caricatural splendour. There are many more examples of iconic pieces presented in the exhibition that we have all heard of without necessarily having seen them, such as Canopus (from the Planetarium series, 1990) by Nam June Paik, another key figure in media art. This brings us to the second observation of the exhibition: the question of the conservation of these fragile works, which require constant maintenance and ad hoc storage conditions. This question, which is indirectly raised by the exhibition “The Story That Never Ends. The ZKM Collection”, is not a marginal one – it involves necessary logistics, something of which the ZKM, as a restoration facility, is particularly aware – but rather that of the conservation of these works and their inestimable heritage value.

Fauteuil roulant électrique avec bras mécanique, lampes, miroir, verre à whisky, moteur, détecteur infrarouge / electric wheelchair with mechanical arm, lamps, mirror, whisky glass, motor, infrared detector : 109 × 79 × 117 cm ; rayon d’action env. / radius of action approx. 600 cm, ZKM | Centre d’art et de technologie des médias de Karlsruhe, ZKM | Centre for Art and Media Karlsruhe © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014.

Head image : Nam June Paik, Canopus, (de la série / from the serie : Planetarium), 1990.

Sculpture vidéo monocanal ; vidéo LaserDisc (couleur, muette, 29 min, transférée sur carte CF), 6 téléviseurs CRT, lecteur LaserDisc (aujourd’hui : lecteur multimédia numérique), enjoliveur, construction en aluminium, lampe à incandescence / Single-channel video sculpture; LaserDisc video (color, silent, 29 min., migrated to CF card), 6 CRT televisions, LaserDisc player (today: digital media player), hubcap, aluminum construction, incandescent lamp.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Global Fascisms, Geister, Modern Love at musée d'art contemporain d'Athènes, Interview Anne Bonnin, Chris Sharp,

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Thomias Radin

by Caroline Ferreira