Modern Love at musée d’art contemporain d’Athènes

In the space of just one year, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens has become a fixture in the contemporary art system in the Greek capital. The opening has been in the works for the past fifteen years and opened only recently; with Katerina Gregos at its helm it would seem the museum has now hit cruising speed. Modern Love gathers together over twenty international artists in a thematic exhibition which, as its name indicates, presents an exploration of todays methods of finding love; particularly with regard to the influence that new technologies— with their various forms, tools and economy—have had on providing new ways of meeting potential mates. The exhibition does not, however, limit itself to a stocktaking of new practices; it also points out the effects technology has had on love itself: the title was borrowed from an essay by Éva Illouz, Love in the Age of Cold Intimacy which seems to indicate that technology has had a cooling effect on romantic partnerships. With love at the centre of the exhibition, the curator has deliberately chosen a subject which has often been sidelined due to its being regarded as not serious enough for consideration within the arts—too anecdotal and therefore subject to much off-topic pseudo-sentimental romanticism. Here, love is presented as a foundational energy and the cement which holds society together. Furthermore, the director and curator of the museum underscores the need to avoid allowing economic strategies which use so-called relationship-based methods to replace the possibility for more conventional, “in-person” meetings to take place, leaving room for chance and the unknown. These types of meetings also allow the possibility for people to get to know the Other; with all of the profound implications the complexity of a slow unveiling of an ego implies; a kind of anecdote to the algorithm and other AI inventions which make more and more decisions as to the relevance of our romantic choices.

Our Cold Loves, 2022 (video still)

Single channel video projection, colour, sound, 32’ 31’’

Courtesy of the artist and Michel Rein Paris | Brussels

Modern Love opens with a work that immediately confronts the viewer with the supposed heteronormativity of romantic love: Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity (2022), a roundabout reproduction of the ruins of the temple of Olympian Zeus, a queer reference in the 1980s, when it served as a rallying point at a time when male homosexuality was still kept mostly beneath the radar—especially in a city like Athens where sexual diversity and the tolerance of LGBTQ+ was far from what could be found in places like New York or Berlin and mores were still largely conservative. Andreas Angelidakis’s installation directly references Greek and Roman architecture through the use of some of its characteristic markers—columns and pilasters which the artist has mollified to allow them to be moved and sat or lain upon—which is also a reference to the erotic traditions of ancient Greece. Same-sex relationships at the time were far from prohibited, the Greek artist therefore also delves into his own “sexual archeology” through this work, consulting sources from the queer underground such as the Athens review, Kraximo.

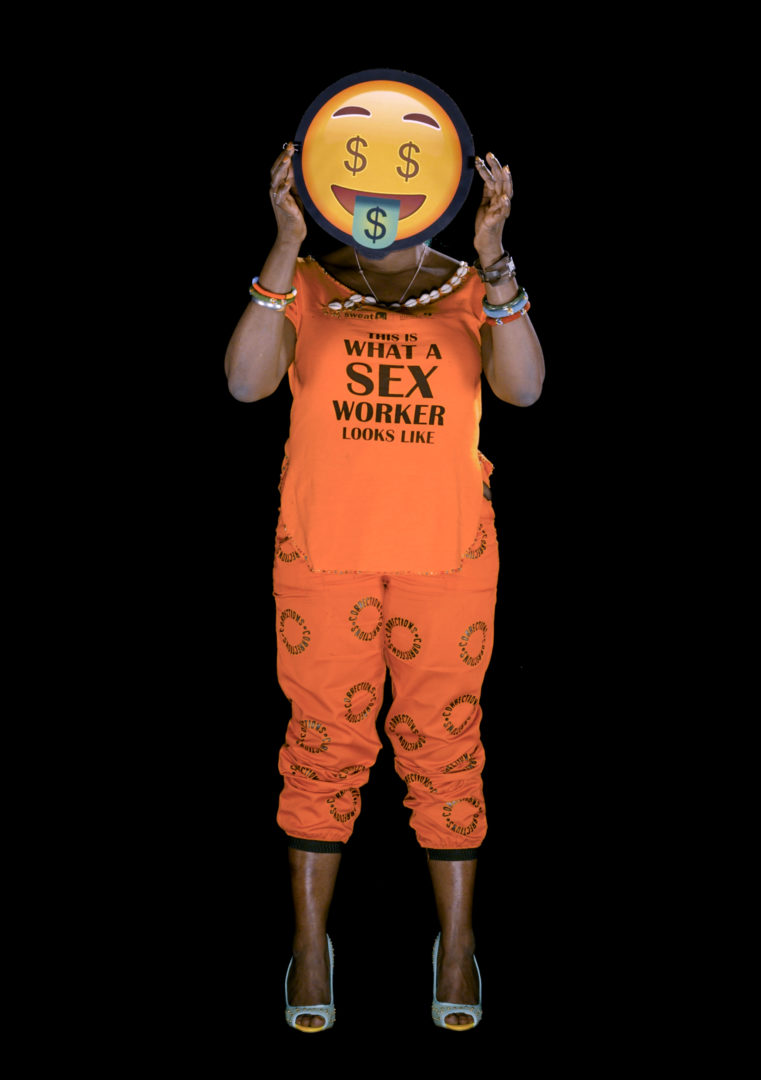

Katarina Gregos’ exhibition is far from a condemnation of the influence of new technologies: it is something more like a state of affairs of contemporary practices in romantic partnership—an incredible upheaval has occurred with the appearance of the internet, making a new type of encounters possible, which had thus been available mainly to a restrained number of savvy individuals, stigmatizing another type in one fell swoop. In a sense, the digital turn has democratised practices which had once been limited to a select few, while it accelerated the emancipation of certain members of society, such as those identifying as LGBTQ+, yet this development toward a new openness came at a price—one of a relative disenchantment and a consumerist slant which was accentuated by the use of algorithms for the sake of matchmaking. Katarina Gregos’ choice of artists reflects an ambiguousness—between a vision which recognises the unbearable omnipresence of AI, for example, which tends to supplant spontaneous decisions in order to subject them to a crippling rationality (Ariane Loze’s hilarious video, If You Didn’t Choose A, You Probably Chose B, 2022) and the powerfully freeing potential of applications like Grindr, which became a political space for the affirmation of the at-risk construction of identity in Egypt in the 2010s (Mahmoud Khaled, Do You Have Work Tomorrow?, 2013). Overall, things are not particularly looking up for romance these days. Marijke de Roover focuses on the heteronormative aspect of viral memes posted anonymously online and which are hostile toward queer identifying individuals; Niche Content for Frustrated Queers, 2019-2020 nonetheless attempts to propagate a completely different sort altogether. Yorgos Prinos’ works turn their attention toward intensely distressed people in candid photographs taken by the artist. While this series cannot be attributed to the rise of the digital era, it does call attention to the intense isolation of unmoored members of society and a sense of reduced community in a society which is increasingly hyper focussed on the optimisation of individual productivity. Laura Cemin depicts herself reuniting with loved ones following long periods of extended isolation due to the confinement; a type of challenge for the artist who developed a phobia which involved the intense fear of physical contact which the steady use of screens only intensified (In Between, The Warmth, 2017-2020). Candice Breitz has one of the strongest works in the show, which bears witness to the difficulties of a group of sex workers: African emigrés in a country they believed would be the land of Cockayne, South Africa, but which turns out to be less welcoming than they had hoped, are pushed into paid sex work in order to stay afloat (TLDR, 2017). These videos steer clear of any hint of shamefulness; instead of hiding themselves, the participants seize the occasion to criticise the terrible living conditions and attitudes migrants are faced with, not without some hope of enjoyment in the future.

Focus Wear, 2020 (installation view)

Various textiles, steel (180 x 50 x 45 cm and 170 x 55 x 45 cm)

Courtesy of the artist

Photo: Pinelopi Gerasimou

On the other hand, the work of Peter Puklus testifies to a clear evolution of societal norms: in some forward-thinking societies, parental roles are moving ever more closely toward a more equal redistribution. In Portrait of Man With Child, this very real revolution within modern romantic partnerships becomes visible, showing how fortunately it is no longer shocking to see men change a diaper or simply care for their children. The installation, The Hero Mother, (2016) takes things one step further, making modifications to objects in order to allow for further liberation.

Modern Love does not, however, seek to downplay the situation by wallowing in desperation, as even many of the works which lean toward negativity are nonetheless lightened by humour, such as Ariane Loze’s works mentioned above, or those by Hannah Toticki which envision clothing and jewellery designed to combat certain addictive habits which characterise our digital era, like the anti-keyboard rings or the screen de-activating headsets; these solutions which are equally vain as they are hilarious prevent the user from spending hours on end in front of a screen. Maria Mavropoulou imagines screens which have taken the place of people themselves (The Lovers, 2018), while David Haines creates a propaganda film destined for homosexuals trying to rid themselves of their hurt by making techno music videos, flipping the script to the point of absurdity (Dereviled, 2013).

Regardless, Modern Love does not take a clear-cut stance with regard to the influence of new technology on romantic partnership—the exhibition does denounce the commodification of feelings and the exponential emodities market, deploring a cooling-off of relationships due to the rationalisation induced by AI and other algorithms—it is rather an opportunity to explore new trends in romantic love in an audacious way in Athens, a city which is known for its overall conservatism.

1 Or emotional merchandise, a term coined by Eva Illouz to refer to the co-production by diverse industries ranging from tourism to psychotherapy for the benefit of self care.

TLDR, 2017 (video still)

13-Channel Video Installation

Commissioned by the B3 Biennial of the Moving Image, Frankfurt am Main

Courtesy of the artist

______________________________________________________________________________

Head image : Maria Mavropoulou, The Lovers, from the Family Portraits series, 2018. Light box, 100 x 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist

- From the issue: 104

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Interview Anne Bonnin, Chris Sharp,

Related articles

Streaming from our eyes

by Gabriela Anco

Don’t Take It Too Seriously

by Patrice Joly

Déborah Bron & Camille Sevez

by Gabriela Anco