Madison Bycroft

Octopus notes

“My mother, the medusa, wants me to be the way I am. So I throw a fit […]. I’m incapable of knowing anything. I don’t have any human contacts. I’m incapable of understanding their language.”

Kathy Acker, Great Expectations, 1983

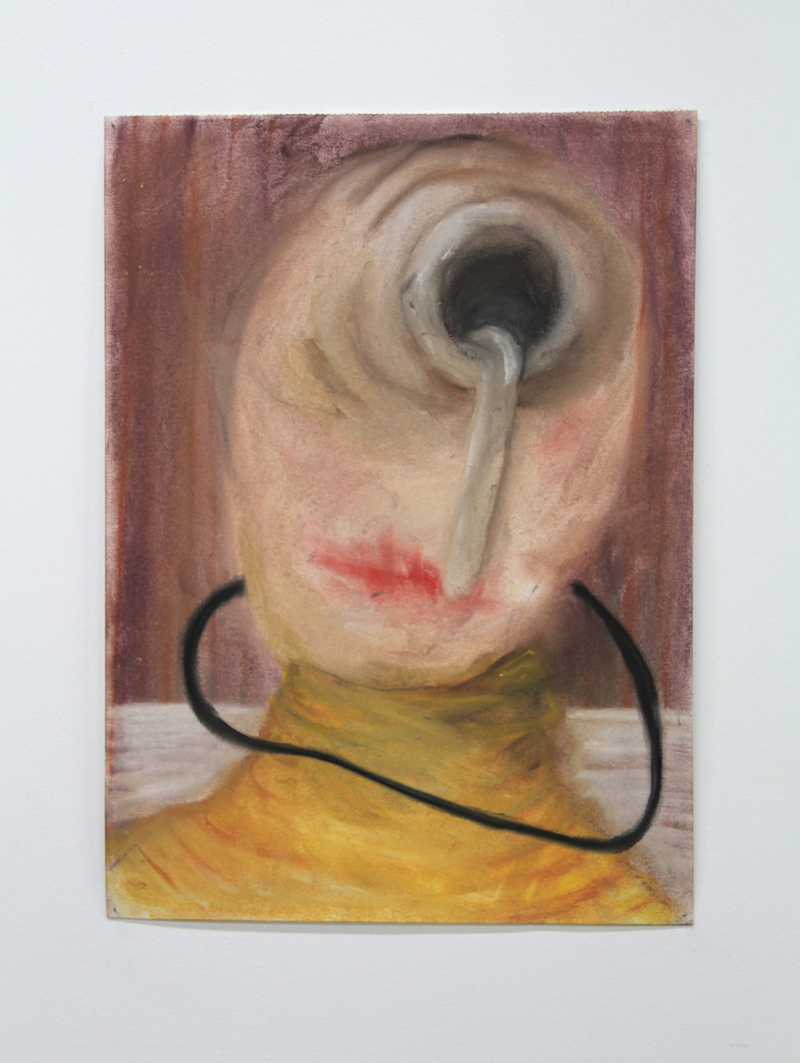

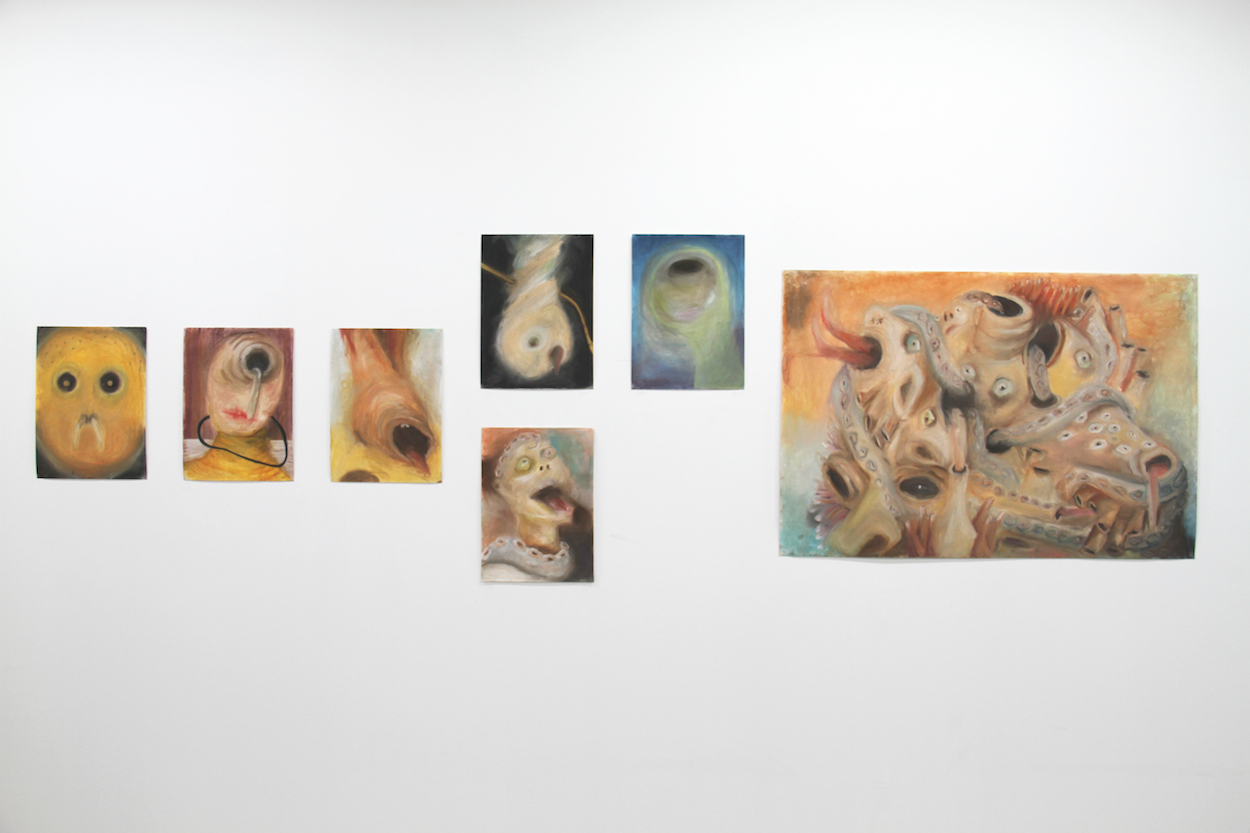

She says she drew them when she didn’t manage to accomplish her daily artist’s tasks like answering her emails, filming herself and submitting applications. Her work doesn’t usually involve such things as sketching portraits of soft-headed creatures with crayons. At the end of August, they were affixed to the walls of an exhibition venue in Marseille which has the same name as the Australian hills in which Madison was born: Adelaide. The drawings rubbed shoulders with a block of plaster frozen in an embrace with an office chair and a video in which the images crumple each other and move from pipe to pipe. We invariably end up reverting to these monsters pulling faces as they stare at us. Some have tentacles which they wear like braids or crowns. A lot of them have a big mouth and suckers, unless they’re eyes, which seem to be fluttering in search of a contact. You get closer to their gaping mouths to look at the dark throats they offer us. Let’s go down.

Go down right to the bottom of the email. A shoal of cuttlefish floats beneath Madison’s automatic signature. The artist’s distorted face is imprinted on their translucent skin. In a video found on the Internet, I’ve seen Madison, still a student, covering her head with an inert octopus, after cutting off her hair with a pair of scissors. The sober quality of this performance, during which she gets ready to have contact with the cephalopod, no longer has much to do with the fluorescent-coloured animations of her latest videos. In them, the deep-sea creatures seem to come more from a Windows screen-saver than from a fish market, but it has to be said that there is still an affinity with the invertebrate. It is at once a research subject, an interlocutor with whom the artist tries to establish communications, and a figure whose rubbery features represent an illustrative repertory which she wittily expresses in her various pieces. But what is involved above all is an additive with which to mull over issues to do with attention to the other, empathy, and, who knows, perhaps love and suffering.

What’s love got to do with it?

Many people have found the love life of cephalopods extremely interesting. In 1967, Jean Painlevé made Les amours de la pieuvre [The Octopus’s Love Life], a documentary film with surrealist overtones shot in an aquarium, in which one can observe, in particular, scenes where two members of the species approach each other and engage. More recently, Chus Martinez published a text titled “The Octopus in Love”1 in which, before displaying an institutional model inspired by the octopus, she described a childhood memory linking a young boy with an octopus which he regularly talked with in the cove of a harbour. In both cases, learning things from the octopus meant plunging into an affective scenario, and an anthropomorphic fiction. Madison raises the issue in a different way. To put herself in the octopus’s place, isn’t it first necessary to question our so-called human form? And is it possible to use the soft body which acts as our tongue to do this?

She recently spelled out these issues during a cycle of performances held in Beirut and Amsterdam, to try and establish a mollusk theory. The first stage (Mollusk Theory: Soft Bodies) begins with a bearded Bycroft wearing boxer shorts, slouched in front of a microphone. At the same time as she details one or two things she knows about cuttlefish, she goes back over the branches of her own species and relates her genealogy. Madison was not born in a shell, but she is the fruit of a love story that began on rocks. The form that came into being through that union is being forever disguised by her throughout the performance, bartering her male trappings for a wig of long blond hair and an impressive cuttlefish costume. The artist’s outlines are softened.

In the last section to date of this cycle, In Lieu of the Limpets Limits, she makes way for a performer who, equipped with a light on his forehead, sinks like a winkle into a sort of membrane, and reads a text out loud. In the manner of a Diogenes in his barrel, the mollusc becomes a teacher and tries to deliver information about how it feels and loves. It ends up rejecting us; it is perhaps from our mutual incommunicability that lessons must be learnt.

Corps corpus corporate

Madison reads a lot of theory. To accompany her performances, she has cut out and put together a certain number of texts, ranging from Jacques Derrida’s L’Animal que Donc je Suis to the humid texts of Clarice Lispector, to form a corpus which she hands out to the audience. The term “corpus” here takes on its full sense because it really does involve forming one body with these writings, and experiencing them. An idea which echoes the thinking of another deep-sea creature. The Laugh of the Medusa, published in 1975 by Hélène Cixous, is a manifesto for the incorporation of the female body in the writing in which she says scoldingly: “We’ll show them our sexts”. And it is under the aegis of the author that another swathe of Bycroft’s reflections opens up.

While undertaking research in the Richelieu Library in Paris, Madison came upon a text by Hélène Cixous referring to a mythological female figure almost as feared as Medusa. L’Après Médée is eleven pages long, and impossible to read for the artist, who doesn’t speak French. So how is this thinking to be incorporated, thinking that is as cryptic as that of an octopus? How is it to be translated? Once again, it is important to multiply. As a two-headed creature, first of all, as was already the case in The Bureau of Neutrality and the Half Sung (2016). The video consisted in particular in a dialogue embarked upon between two modelizations of Madison’s face which, in commenting on a Caravaggio picture in a certain cacophony, brought out the fact that the artist qualifies as a “middle voice”, a voice situated halfway between the subject, its reflection and its object. The discovery of the Cixous text pushes this logic a bit further. During several workshops held in Athens, Marseille and Rotterdam, Madison brought several people together around the essay with the aim of trying to translate it page by page (Translating Medea). Helped by the figure of the octopus, this is a form of tentacular thinking which is introduced around the text. The goal is obviously not to produce an English version which would help to understand precisely what it contains. What is involved, rather, is several people performing actions that incorporate thought and, in a sense, taking care of Cixous. Because, as theoreticians of language such as Gayatri Spivak1 have declared, the exercise of translation puts to work the muscles of solicitude and empathy for what is decidedly alien to us.

Madison is aware of the capitalist economy within which these issues of systems of attention and care are rooted. So it is amusing to see how the sea bed sometimes encounters a continent where solicitude is a commodity which is merchandized in a thoroughly corporate spirit. The artist perfectly incarnates its representatives, from the figure of the coach, Rayleen, a mellow-voiced trainer at the bottom of the aquarium in the video Separations Inc., to that of Hugh, who, in Mollusk Theory, boasts to a shoal of attentive performers the merits of a “human resources” department, with regard to which we may wonder what it might have to offer to invertebrates.

We could carry on going down. And perhaps on the Marseille coast we might find the artist who says she does diving training every day.

1 Chus Martinez, “The Octopus in Love”, e-flux journal #55, May 2014.

2 Damien Tissot, “L’universel et l’éthique du care en traduction”, Les Ateliers de l’Éthique, Volume 10, No. 3, Autumn 2015, p. 122-148.

(Image on top: Madison Bycroft, Separations Inc.™, 2017. Video.)

Madison Bycroft will be part of the exhibition“Desk Set” to be held at the CAC Brétigny from 10 February 2018.

- From the issue: 84

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Merlin Carpenter - "What’s so elastic about you ?", Corentin Canesson, Jacqueline de Jong, Celia Hempton, Charles Atlas,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset