Lili Reynaud Dewar

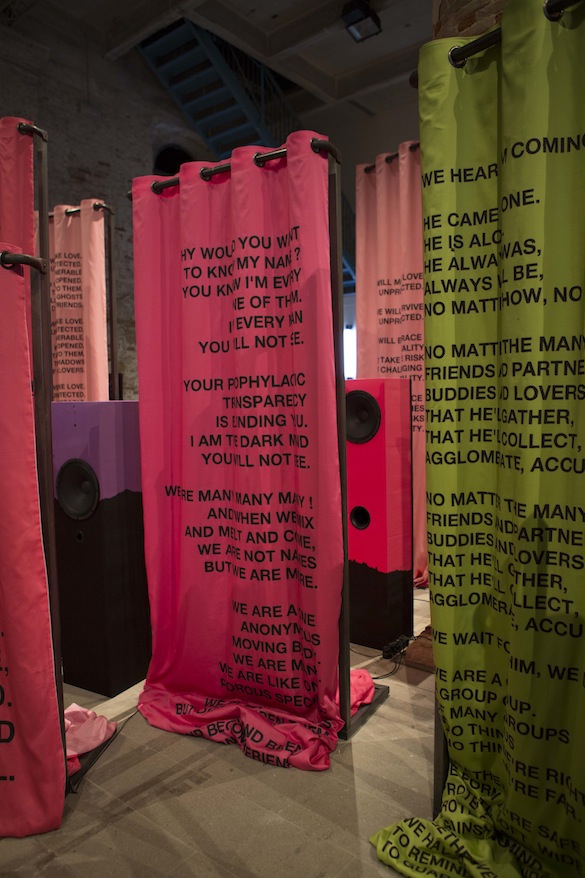

Lili Reynaud Dewar, My Epidemic (Small Modest Bad Blood Opera), 2015. Installation. Fabric, ink, paint, metal, speakers, amplifiers, videos, LED screens, audio track, 29 min 58 s. «All the World’s Futures», Arsenale, 56e Biennale de Venise, 2015. © Lili Reynaud Dewar. Photo : Fabrice Seixas Courtesy C.L.EA.R.I.N.G., New York/Bruxelles ; Emmanuel Layr, Vienne ; kamel mennour, Paris. With the support of Institut français ; Fondazione Querini Stampalia.

The “opera” that Lili Reynaud Dewar has just put on at the Venice Biennale takes up many of the concerns she already broached during her thus far short but very busy career. Although opera seems to be slightly anachronistic in an age that prefers fast checking works on Instagram, this art form nevertheless represents a natural extension for an artist who has always been interested in “all-encompassing” matricial arrangements, like the Black Maria which, in its day, was a veritable crucible in which the first performances of all time were undoubtedly recorded, and whose name she borrowed for one of her shows. Opera is an optimal form insomuch as it associates almost all the artistic praxes—song, music, dance, writing (libretto), and sculpture (décor, set design)—to which the artist has added an art “of our day and age”: video. Reynaud Dewar’s “machines” do not just represent a way of thinking about the evolution of contemporary art formats; they are also used to take an in-depth look at the society we are living in: by once again highlighting the extremely virulent discussions about Aids in the 1990s, Lili Reynaud Dewar is re-invigorating the social debate by re-posing the question of artistic responsibility. The form of her installations, from her very earliest exhibitions on, offers a renewed look at the exclusionary phenomena of minority cultures and deviant figures: her grasp of the stage object situates her in the direct line of illustrious predecessors who, like Mike Kelley, managed to raise anew the issue of the incarnation of the art object, and shed light on the various kinds of discourse hidden behind the appearance of neutrality; her “visitation” as a skipping black angel to the cult sites—and/or places of worship—of contemporary art in her latest filmed performances is nothing less than a way of cocking a snook at the art establishment.

Performance is the Matrix

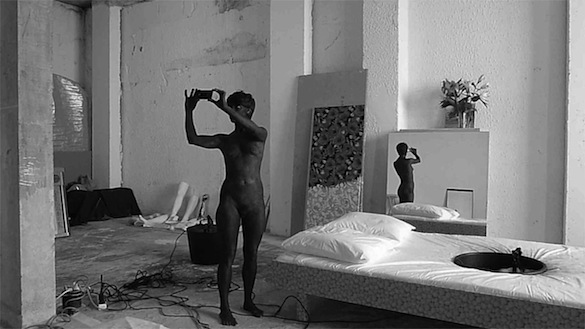

Lili Reynaud Dewar, I Am Intact and I Don’t Care, 2013. 12e biennale de Lyon. Courtesy Lili Reynaud Dewar ; Clearing

Lili Reynaud Dewar, Live Through That?! (New Museum, New York), 2014. Video (mute) Courtesy Lili Reynaud Dewar ; kamel mennour, Paris

In 2006, in “The Center and the Eyes1”, one of the first major exhibitions of Lili Reynaud Dewar’s œuvre, most of the significant elements of the artist’s work were there in embryonic form, including the installation of a stage-like arrangement devised with the purpose of accommodating performers. Performance was in fact the central factor of this matricial system which made it possible to introduce interaction among the many different issues running right through the artist’s work: gender, minorities, origins, high and low culture, the status of objects; performance is the conceptual cauldron which helps to merge all these references, and rekindle the synaesthesia dear to modernism. So it is hard to talk about a body of work which borrows from all the dimensions of art, from poetry to music, by way of design, video and literature. The one big thing missing is perhaps painting, unless we regard Lili Reynaud Dewar’s praxis as the production of something unique formed by a whole host of artistic contributions which are undoubtedly aloof from one another, but, in the end of the day, do have a real plastic unity, like a tableau vivant or living picture, in a way… The true major reference is perhaps that of the Florentine festival of the Renaissance which, on the pretext of paying tribute to the figure of the prince, consisted in associating the greatest number of “trades” in the production of a total form, a concentrated firework in a short-lived paroxysmal production, “an Italian festival which, according to Jacob Burckhardt as quoted by Aby Warburg, at its higher degree of civilization, really does create a shift from life to art”,2 a theatrical festival which represented a climax in the collusion of praxes, and in a way anticipated postmodernism when modernism invariably tried to refine forms in an impossible convergence. The major difference with those large stage machines of the 16th century, which revolutionized the way spectacles were presented, is that Reynaud Dewar’s performances are filled with demi-gods and eccentric creatures, rebels avoiding any full recognition because they refuse the codes of celebrity by upsetting the established order and conservatism, while Renaissance festivals were intended to magnify the figure of the patron. The characters presented by Lili Reynaud Dewar in her shows form a pantheon of anti-heroes, the most emblematic among them being Guillaume Dustan and Sun Ra, both figures who are, to say the least, controversial, and who have remained on the sidelines of the main distribution circuits, in Sun Ra’s case, while a character such as Dustan fairly and squarely became the pariah of French literature, prior to a late-in-the-day recognition that has given rise to a recent re-publication of his writings.3

Lili Reynaud Dewar, Black Mariah (The Woman’s Performance Objects and films), 2009. Wood, mirrors, leather, paint, costume, posters and video. View of the installation, Centre d’art du parc Saint Léger, Pougues-les-Eaux, 2009. Photo : Aurélien Mole. Courtesy Lili Reynaud Dewar ; kamel mennour, Paris

The exhibition, simply titled “Black Mariah”, which was held in 20094 at the Parc Saint Léger leaves no doubt as to the homage being paid to that very first ‘black box’ in history. Built at the end of the 19th century with the goal of optimizing the potential of Thomas Edison’s latest inventions, that box became, de facto, the very first studio producing moving images. Over and above historical anecdote and the almost supernatural character attributed to the Black Maria productions, it was the incredible procession of characters of every shape and form—including that group of Indians who were part of the Buffalo Bill Show tour and, for the occasion, executing what might be described as one of the first filmed performances in history—which helped to create the legend of that unbelievable machine. In the arrangement which the artist set up at Pougues-les-Eaux, she tried, in a fragmentary way to be sure, to reinstate that twofold function of stage direction and recording, by making a continuous video production in the exhibition spaces of the art centre. In that show, Lili Reynaud Dewar went back to the spatial issues of her 2006 exhibition, in which the stage objects played a quintessential part. At once sculptures, parts of a set, props, and fetishes, her stage objects issue from many different layers of intent, which certainly jostle the usual reflexes to do with understanding artworks: in “The Center and the Eyes”, the spectator was faced with the possibility of a frontal and spatial discovery of the sculptures, which gave him/her the impression of being in a fourth dimension;4 at Pougues, in responding to the sophistication of the Black Maria capable of following the sun’s curve in the sky, Reynaud Dewar created a space capable of carrying out many different successive and simultaneous missions: filming location co-existing with upstream storage areas, a mezzanine where films made in situ would be screened and, lastly, an area where exhibition visitors could move about, with the whole thing keeping the same stage objects throughout the whole process.

Lili Reynaud Dewar Live Through That?!, 2014. Installation view New Museum, New York. © Lili Reynaud Dewar Photo : Benoit Pailley Courtesy Lili Reynaud Dewar ; kamel mennour, Paris ; C.L.E.A.R.I.N.G, New York & Brussels ; New Museum, New York. With the support of Fondation d’entreprise Ricard.

The Prime Prop

The public at Lili Reynaud Dewar’s exhibitions thus finds itself in a paradoxical position: unlike the “classical” performance, which calls for dismantling everything at the end of the show—panels, props, screens, notices etc. —, here the objects stay where they are, and then revert to their more classical status of sculpture.

The artist’s position, as far as the objects connected with the performance are concerned, overlaps with the reflections of her predecessors, by re-charging them with an undeniable vitality. One of the solutions offered by Guy de Cointet for the question of the status of the stage object was that this object should, as far as is possible, conserve a utilitarian dimension, by returning it to where it belongs once its use on stage is over. The complexity of the links that de Cointet had with objects cannot, however, be summed up in their reversion, at a given moment, to their status of functional object, and, throughout his career, the artist has got them to play the most diverse of roles, proceeding as they do from prop status to the condition of the phoneme, taking part in a structured whole that refers to the way language functions. Lili Reynaud Dewar’s relationship to objects seems closer to the connection that Mike Kelley highlights in his text Playing with Dead Things:5 the American artist refers to the items placed in the tombs of ancient Egyptian dignitaries to accompany them on their journey to the hereafter. The reference to ritual voodoo objects made by Reynaud Dewar can also be read as a criticism of western art objects, objects whose activation reaches its height when they are included in the performance scenario, but which, once the excitement of the spectacle is over, fall back into their awful lethargy.

Lili Reynaud Dewar, Untitled, 2013. Book, wood, fabric. Courtesy Lili Reynaud Dewar

Contrasting ritual objects with modern and contemporary sculptures, as Reynaud Dewar allusively does, is to broach the postcolonial issue by way of the fine arts system which represents the quintessence of the West’s cultural superiority: it actually involves introducing minority representations straight into the conventional exhibition system, which imposes an extremely well signposted organization of the gaze, and consequently disturbing this organization. The artist would incidentally take a zigzagging itinerary where this subject is concerned, right to this very latest phase of the danced performances. In the meantime, she returned to a production of objects with more pop outlines. The reference to Italian designers like Ettore Sottsass nevertheless marked both her hesitation about going back to a more usual version of sculpture and her reluctance to abandon the object’s functional dimension. The show at the Parc Saint Léger presented several volumes in the form of numbers and letters, as if the conversion to pop sculpture could only be made at the price of a concession made to this latter’s utilitarian dimension, or at the very least to any “reading” of it. A new turnaround took place with the dance performances which the artist put on in 2011 in the middle of her works, almost abandoning that careful finish, and temporarily returning to a more modest series of objects in the way they are made—in whose continuity Untitled (2013) see arranged on a stand covered in fabric with African motifs Brian O’Doherty’s famous book White Cube, whose cover and inside pages are soiled by black imprints which stand out clearly from the whiteness of the paper: there is scarcely any doubt about the meaning of its message, the symbolism of the denunciation of the reign of Western-centrism is direct and immediately readable. What a Pity You Are an Architect, monsieur ! You’d Make a Sensational Partner (2011) marks an abrupt break with the previous episodes: in it, the artist is naked, completely coated with a layer of black pigment, dancing in the middle of those same pieces. The actors making up the small troupe have disappeared: from now on the artist performs on her own. The distancing peculiar to video accentuates reification; the works tend to be part of a devitalized décor. The tone she gives to the emblematic places which play host to the filming of these performances, which she would increase in number from 2011 on—art centres, large museums, as well as artist-run spaces—, remains problematic because, having been wittingly chosen by the artist for their recognized programming, they are “re-visited” by the mocking and merry spirit of a mini-Josephine Baker, which is tantamount to saying, once again, that people of colour only gain access (have never gained access) to the temples of western culture by way of the authorized route of dance and the burlesque.

Lili Reynaud Dewar, My Epidemic (Small Modest Bad Blood Opera), 2015. Installation. Fabric, ink, paint, metal, speakers, amplifiers, videos, LED screens, audio track, 29 min 58 s. «All the World’s Futures», Arsenale, 56e Biennale de Venise, 2015. © Lili Reynaud Dewar. Photo : Fabrice Seixas Courtesy C.L.EA.R.I.N.G., New York/Bruxelles ; Emmanuel Layr, Vienne ; kamel mennour, Paris. With the support of Institut français ; Fondazione Querini Stampalia.

Staging literature/in pursuit of a diffracted identity

Lili Reynaud Dewar has quite a passionate interest in literature: certain authors have pride of place in her personal pantheon, with Marguerite Duras and Guillaume Dustan clearly standing apart from the rest. The inclusion of literature in his/her œuvre is nothing less than a puzzle for an artist trying to implant a literary opus in the depths of a plastic intent, but not content to draw inspiration from the themes developed by the author. It is one thing to be inspired by a literary atmosphere and translate it into the world of visual arts, and it is quite another to really get seemingly irreconcilable forms to merge, and it is, incidentally, this seeming irreconcilability which seems to be one of the most fertile areas of contemporary art. In so doing, Reynaud Dewar wavers between these two tendencies, between a desire to formally merge the fields and the more ordinary desire to be in a state of very marked empathy with a line of thinking, a relation to existence whose translation proceeds via an extremely “classical” utilization of the text. But as with her praxis as a whole, the artist tries out different positions and effects permanent back-and-forths, shifting from a metaphorical approach to literature, and thus from a somewhat imagery-rich transcription of what the reading of one her favourite authors managed to give her, to a quite different style. I am intact and I don’t care (2013)6 can, for example, be understood as a fairly probing allegory of writing: a bed with a hole in the middle of it, from which a small spout of ink escapes. It is easy to re-make the meaningful puzzle ourselves, and see therein a psychoanalytical and more or less traumatic interpretation, if we want to be satisfied with a psychologically-oriented reading of the work (is it her reading of Duras that led her to create this work with its deleterious spirit, or rather her reading of Dustan, for whom existence is filled with similar wells of creative darkness?). As far as the second tendency is concerned, it so happens that Reynaud Dewar uses texts in a very literal way, brandishing them like so many banners bearing more or less provocative slogans. So when Live Through That?!7 was shown at the New Museum, it filled the museum’s ground floor with large hangings on which Guillaume Dustan’s writings appeared very distinctly, introducing a close collaboration between text and set. At the Venice Biennale,8 we find very much the same procedure, but with just the basic difference that the texts presented on the curtains are by the artist herself: they are part of a more complex arrangement in which we find videos of performances filmed in Venice, as well as numerous other scenographic elements. Other aspects of the installation evoke the effects of writing, one such being this capillarity which makes the ink move upwards over the stage objects and panels which stop us seeing the monitors: it is the metaphorical aspect which predominates here, the aspect involving the contamination of everything by writing. Here we rediscover one of the artist’s favourite procedures: the introduction of matricial arrangements which, like the Black Maria, make it possible to combine praxes, and get them to be part and parcel of a general movement. My Epidemic (small modest bad blood opera) is an opera—and, for Italians, opera is the ultimate art form, combining song, music, décor and theatre with writing—, an opera that is nothing if not tragic, presenting the character of Guillaume Dustan, and delving deeply into the arcana of a disquieting work that has suffered the wrath of associations like Act Up, which accused him of spreading propaganda in favour of an attitude that was irresponsible because it endangered the lives of his partners during unprotected sexual relations. Dustan himself had always advocated a totally unfettered sexuality: his literature resembles him, a radical, straightforward literature, repetitive and as anti-novelistic as you can get, a literature which explores his own desire and challenges proximity with danger, a combative literature of introspection, which incidentally drew him close to the one of Marguerite Duras, whose ability to lay herself bare he admired.

In tandem with the work that she developed for the Arsenal, Reynaud Dewar took her HEAD students from Geneva to Venice to follow that nomadic seminar that she has been working on for several years, and which consists in discussing/debating her favourite subjects as a small group in her hotel room—subjects which often revolve around gender issues but also around all kinds of literature and poetry. With her students in Venice, it goes without saying, she read texts by Dustan, but also writings of Douglas Crimp9,Eileen Myles and Samuel Delany, trying to re-visit the context of the anathema that Dustan underwent in the light of new approaches, re-questioning personal commitment and artistic responsibility within a far larger questioning, at the hub of which the issue of the subject rises to the surface, along with its fragmentation and the reconstruction strategies of this latter by contemporary art, and by literature…

View of the exhibition «The Center and the Eyes», Zoo galerie, Nantes, 2006. Courtesy Lili Reynaud Dewar.

1 “The Center and the Eyes”, Zoo galerie, Nantes, from 19 October to 19 November 2006.

2 Philippe Alain-Michaud, Aby Warburg et l’image en mouvement, Macula, 1998.

3 Guillaume Dustan, Œuvres I, preface by Thomas Clerc, Paris, P.O.L., 2013.

4 “Black Mariah”, Parc Saint Léger, Pougues-les-Eaux, from 29 March to 24 June 2009.

5 “In the Zoo galerie space, divided at its centre by a series of columns, Lili Reynaud Dewar has arranged two series of three sculptural elements placed successively in the space. A mouth, a nose, then two eyes thus form, in a perfect symmetry, a black griot and a white griot, tribal figures of the rastafari culture, regarded as trustees of the oral tradition. […] We discover the exhibition both frontally and spatially, aware that it thus presupposes “crossing” the plane and undergoing the experience of the cut (the mouth, nose and eyes are thus dissociated so as to be considered on just an individual basis), which confronts the viewer with the experience of the fourth dimension, that of time”. Claire Jacquet, “Si A = B en art comme en science alors vers quel monde allons nous ?” 02 n°40, winter 2006-07, p. 30.

6 Cf. Marie de Brugerolle “From book to stage prop : theater, actresses, doctors, camp”, in Guy de Cointet, JRP Ringier, 2011, p.76 ff.

7 I am intact and I don’t care, shown in particular at the 21er Raum-Belvédère, Vienna, from 20 March to 14 April 2013 ; in the exhibition, “Enseigner comme des adolescents”, Le Consortium, Dijon, from 3 May to 16 June 2013 ; in the exhibition for the 15th Prix Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, “La vie matérielle”, Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, Paris, from 6 September to 2 November 2013, where the artist was awarded the prize; and at the Lyon Biennale, from 12 September 2013 to 5 January 2014.

8 “Live through that ?!”, New Museum, New York, from 15 October 2014 to 25 January 2015.

9 56th Venice Biennale, “All the World’s Futures”, Arsenal, from 6 May to 22 November 2015.

10 The reference to Douglas Crimp is quintessential, because is puts the discussion on the level of the extreme moralization of the 1990s in the wake of the positions taken up by associations fighting against Aids in particular. The guiltiness and stigmatization of “careless” positions were also in the line of fire: this also led to the issue of privacy and the boundaries of the private space. (Cf. Interview with Lili Reynaud Dewar published in Francis Dommergue’s blog hosted by Médiapart : http://blogs.mediapart.fr/blog/bertrand-dommergue/060515/lili-renaud-dewar-contamine-la-biennale-de-venise-en-chantant).

- From the issue: 74

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Tohé Commaret, Jack Warne, Alun Williams, Ben Thorp Brown, Mircea Cantor,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset