Julien Creuzet

From Caen to Turin, Paris to Dakar and Lyon to Chicago, Julien Creuzet’s work has in recent years enjoyed conspicuous visibility, tacking from A to B by developing a line of thinking that is steeped in movement and relations. If this artist’s titles have an essential place, Opéra-archipel acts as a programmatic statement. From opera, channelling the spectre of the total artwork, he retains the profusion and collision of media, the links that are woven between voice, sculpture, body and music, in a logic no longer of the closed totality but of the fragment and of scattering, preferring addition to absorption. Enter the key notion of archipelago, hallmarking a discontinuous geographical space, a string of islands emerging here and there from the waves to form a network formed by dotted lines, but no less coherent for all that. It also refers, needless to add, to the Antilles, where the artist grew up (in Martinique, to be precise), and to their literary and cultural sphere, and in particular to Edouard Glissant and his “archipelagic thinking”, including the concepts of “Tout-Monde/Whole World”, “relation” and “creolization”, developed as a reaction to the concepts of globalization and universality, which run through the entirety of Creuzet’s work. He is obviously not the first artist to summon such principles, but with him they seem to find a form of transparency and even literalness, and introduce a compatibility between plastic, affective and theoretical challenges.

Opéra-archipel, which was started in 2015 during a residency at La Galerie, the contemporary art centre in Noisy-le-Sec (F), encompasses videos, sculptures, texts and performances, with each fragment being provided with a subtitle which makes it autonomous, while at the same time incorporating it within a shifting cluster, corresponding less to a logic of TV series episodes than to a logic involving a constellation. Based on sources such as Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Indes Galantes and the magazine Toutes nos colonies, published in the 1930s, this multi-facetted project focuses on exploring the mechanisms which, in the West, have fashioned an imagination associated with a fantasized faraway place, and one to be detected in our feeding and clothing habits, in our gestures and dances, in the architecture and vegetation of cities, and in the surviving examples and new faces of this exoticism. It probes these at times threshold and potentially friction-prone zones where the elsewhere and the here, the past and the present, and the private and the collective all meet. Through his works, Julien Creuzet plays with exoticism in an ambiguous way. He is not trying to get rid of it, but rather to shift it by grasping it in terms of circulation and relation.

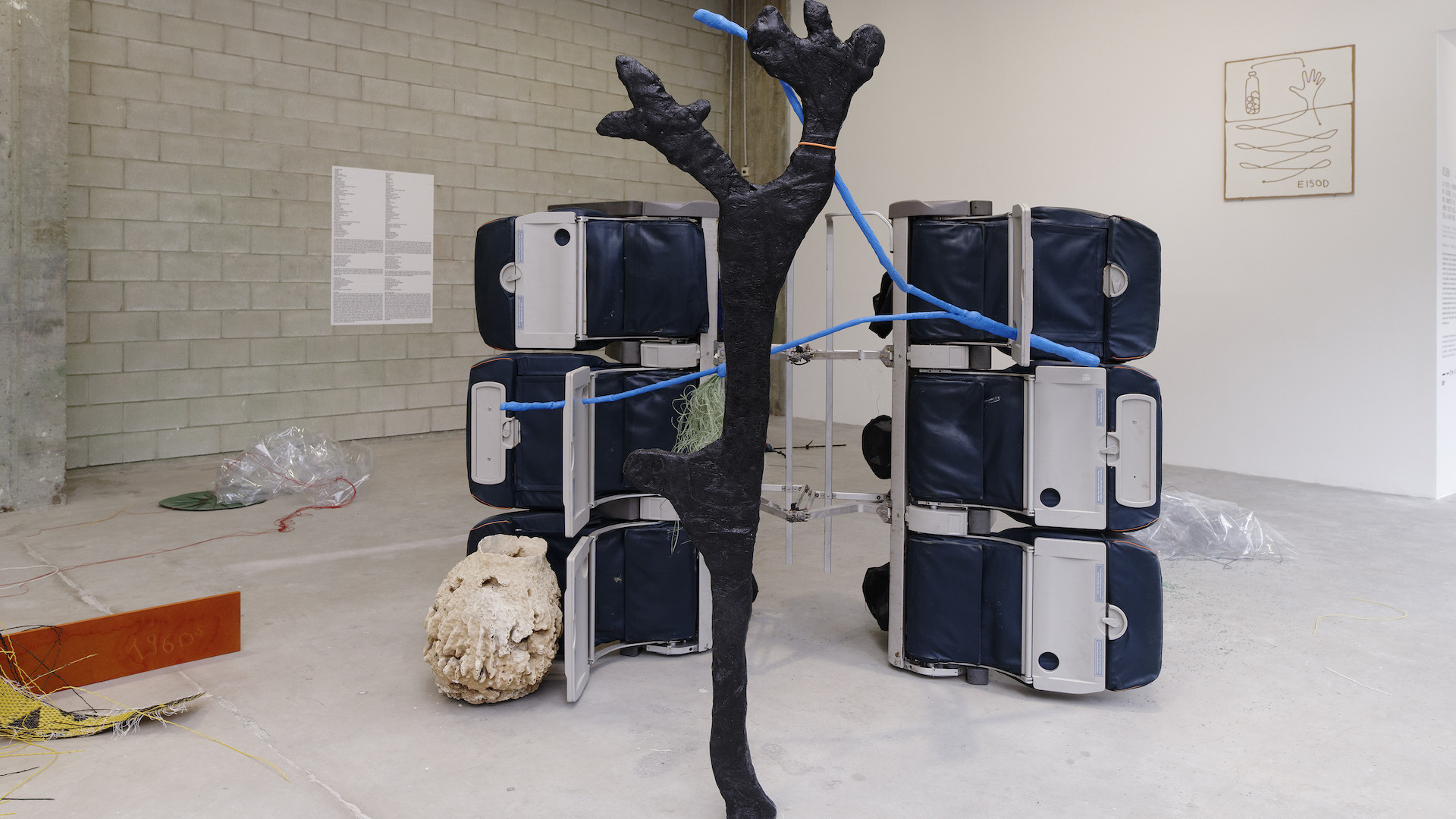

Julien Creuzet, La pluie a rendu cela possible depuis le morne en colère,

la montagne est restée silencieuse. Des impacts de la guerre, des gouttes missile. Après tout cela, peut-être que le volcan protestera à son tour. — Toute la distance de la mer (…), 2018.

Photo : Auélien Mole / Bétonsalon – Centre d’art et de recherche.

These issues of migration and identity lie at the heart of the double exhibition which the artist is putting on in tandem, under the aegis of Mélanie Bouteloup, at the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard and at Bétonsalon, in Paris. Like the two sides of the same coin, each chapter-like venue has a disproportionately lengthy title, already acting as a narrative, taken from a poem which gives structure to and binds together the whole proposition: “The rain made it possible, in the wake of the angry Morne, the mountain has been silent. Impacts of war, of missile drops. After all this, perhaps the volcano will protest in turn.—All the sea’s distance (…)”, for Bétonsalon, and “All the sea’s distance, so that the oily filaments of the manchineel trees stop our heartbeats.—The rain made it possible”, for the Fondation Ricard. Through this loop, this to-and-fro made by the association of the two titles, where water invariably plays a central and ambiguous part, we understand the degree to which the exhibition represents for Julien Creuzet an opportunity to introduce fictions from which, without him seeking to explain their ins and outs, there emerge histories of movements (of peoples and cultural goods alike, vegetal and animal), of shipwrecks and hurricanes, tropical plants and poisonous sea creatures, of colonial repression and ecological catastrophe, economic trade and the finiteness of the human species. So many narratives of flux and stream on which is set the flow of the person who, for a moment, imagined becoming a rapper, and whose song, backed by a female musician, rings out in the space (a soundtrack dedicated to each venue), accompanying the viewer as he strolls about and holding together the different links in the narrative weft created by the show. The words have no discursive significance. They do not play the part which is that of a caption for a picture, but function more as a presence which shares and connects, in the manner of the storyteller’s voice, who, as Walter Benjamin wrote, has “the ability to exchange experiences”,1 based on his own or on those that have been transferred back to him, without ever trying to intermingle explanations.

Julien Creuzet, Toute la distance de la mer, pour que les laments à huile des mancenilliers nous arrêtent les battements de cœur. — La pluie a rendu cela possible (…), 2018.

Photo : Aurélien Mole / Fondation d’entreprise Ricard

With regard to the formal dimension of Julien Creuzet’s work, it is tempting to compare the figure of the Benjaminesque storyteller and the bricoleur or improviser, cobbling things together, whom Claude Lévi-Strauss describes in The Savage Mind as building up “structured sets, not directly with other structured sets but by using the remains and debris of events: in French ‘des bribes et des morceaux’, or odds and ends in English, fossilized evidence of the history of an individual or a society”.2 And it seems quite logical that, through this archipelagic thinking which informs the artist, assemblage and collage practices have a special place. His works are in fact devised on the basis of eclectic materials gleaned and picked up here and there, manufactured objects and items of everyday life like natural elements, which interest him for their symbolic and cultural content, as if they held “messages […] which have to some extent been transmitted in advance”.3 In this way, plasma screen and cellphone, cabin and airplane seat, fossil and shell, secondhand clothing and wooden statuette, orange blossom and rose water all supply a formal repertory that is always in motion. If they are sometimes exhibited as readymades, these different components are usually the object of manipulations which give rise to new images and meanings. An African mat which he unweaves and associates with a piece of jean or an MDF plank, just like tubular forms made from melted coloured plastic—in which various artefacts at times appear absorbed as if in a phenomenon of concretion—might, for example, depict a plant or a piece of seaweed, and trigger a whole host of interpretative avenues. At the Fondation Ricard and at Bétonsalon, petroleum, which is ubiquitous mainly by way of plastic but also because of the food dye with which the artist covers certain surfaces, seems to spread through the various areas. Like an echo of the toxicity figures referred to by the titles (the manchineel tree and the Portuguese galley), it might equally refer to the ups and downs of the world economy and the geological nature of the seabed. Despite the subjects broached and certain gestures (burning, hollowing, undoing, etc.), the archipelagos set up by Creuzet are nevertheless not seeking to collide or clash with the spectator; on the contrary, what results is a paradoxical tranquillity.

Julien Creuzet, Toute la distance de la mer, pour que les laments à huile des mancenilliers nous arrêtent les battements de cœur. — La pluie a rendu cela possible (…), 2018.

Photo : Aurélien Mole / Fondation d’entreprise Ricard

It is, incidentally, not easy to include his work within a precise referential field. If the symbolic use of certain objects may call to mind the procedures of artists who have worked on African-American identity and post-colonial issues—figures such as David Hammons, Rashid Johnson and Kapwani Kiwanga—, Creuzet’s practice of assembling more or less rough and ready sculptural works, consumer goods, video, poetry and fiction tends to liken him, in certain respects, to artists whose concerns are, on the face of it, well removed from his—such as David Douard, Sarah Tritz and Paul Maheke. Whatever the case may be, and without trying to make decisions about liaisons, Julien Creuzet patiently unfolds his complex narratives by applying a theoretical and formal apparatus which is endlessly seeking to produce the unexpected, as in any creolization process.

[1] Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller: Observations on the Works of Nikolai Leskov”, 1936.

[2] Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind, University of Chicago Press, translated from the French by George Weidenfield and Nicholson Ltd.

[3] Ibid, p.34.

(Image on top: Julien Creuzet, La pluie a rendu cela possible depuis le morne en colère,

la montagne est restée silencieuse. Des impacts de la guerre, des gouttes missile. Après tout cela, peut-être que le volcan protestera à son tour. — Toute la distance de la mer (…), 2018. Photo : Aurélien Mole / Bétonsalon – Centre d’art et de recherche.)

- From the issue: 85

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Nora Turato, Ismaïl Bahri, Flora Moscovici, Eva Barto,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset