Eva Barto

Speculative Clues

When you walk into an Eva Barto exhibition, it’s like venturing into an uncertain area filled with false friends, traps, utilitarian and administrative objects either displaced, replicated or damaged, filled with a mysterious aura, at times paranoid, and figures of forgers, big-time gamblers and cheats. There is definitely a whiff of swindle and imposture. In the show, paradox and ambiguity are shrewdly cultivated. Nothing spectacular or decorative here. Eva Barto prefers a task of exposing to the introduction of a comfort zone, a task fuelled by the need to explore the mechanisms of an exhibition, while at the same time becoming more and more detached from the need to become involved in such a mode of appearance. She blurs the horizons of the spectator’s expectation and brings in the possibility of a failure, of passing by the proposition or, on the contrary, of plunging fully into the situation from which she weaves the slender scenario, in a serious and offbeat way.

The typology of the forms produced by Eva Barto conveys an interest in objects with an undefined presence and status, as for a rough treatment of space: ashtrays and stubbed-out cigarette butts letting a smell of cold tobacco waft across, nicked and burnt plasterboard walls, duplicata of budgetary and legal documents, empty display cases, T-shirts drenched in oil, inked stamps, a plastered ticket office, clothing rails, a replicated bike abandoned in the street, a counterfeit coin… All so many familiar objects, damaged, devalued or transformed, attesting to a ghostlike activity, a negotiation or a transaction, and which end up—in the manner of clues to be deciphered and at times exhumed (some of them are hidden between two partitions, in the possession of the mediator or presented outside the gallery)—at the heart of a series of arrangements and a networking of meanings. In this painstaking investigation where it is all about details, some elements may potentially elude the visitor, while others, on the contrary, foreign to the artist’s intervention, may appear for what they are not. They function like autonomous organisms playing and reacting with the environment and the topography of the exhibition space, while forming a constellation, the different nerve centres of an overall discourse.

In trying to shed light on the roots of a paradigm of the clue in the human sciences, the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg evokes the hunting forays of our ancestors who had learnt how to “recreate the shapes and movements of invisible prey based on imprints left in mud, snapped branches, excrement, tufts of hair, plucked feathers, and stale smells”.1 In the decoding of these traces which link man to his surroundings, he reveals the hypothesis of the appearance of the narrative—“the hunter would have been the first person ‘to tell a story’ because he alone was capable of reading a coherent series of events in the silent (if not imperceptible) traces left by prey”2—seeing in them the premises of the slow historical process leading to the invention of writing. Like the symptoms revealed by Freud, or the clues picked up by Sherlock Holmes, these at times imperceptible signs make it possible to grasp a deeper reality. In Eva Barto’s work we find this muddle of tracks, fictions to be woven, and underlying reality which, if we gradually get rid of the slightly invasive image of the police investigation, tends less to describe a “that’s how it was” than propose a zone of speculation or, to use the words of the artist Victor Burgin, “an occasion for interpretation rather than consumer objects”.

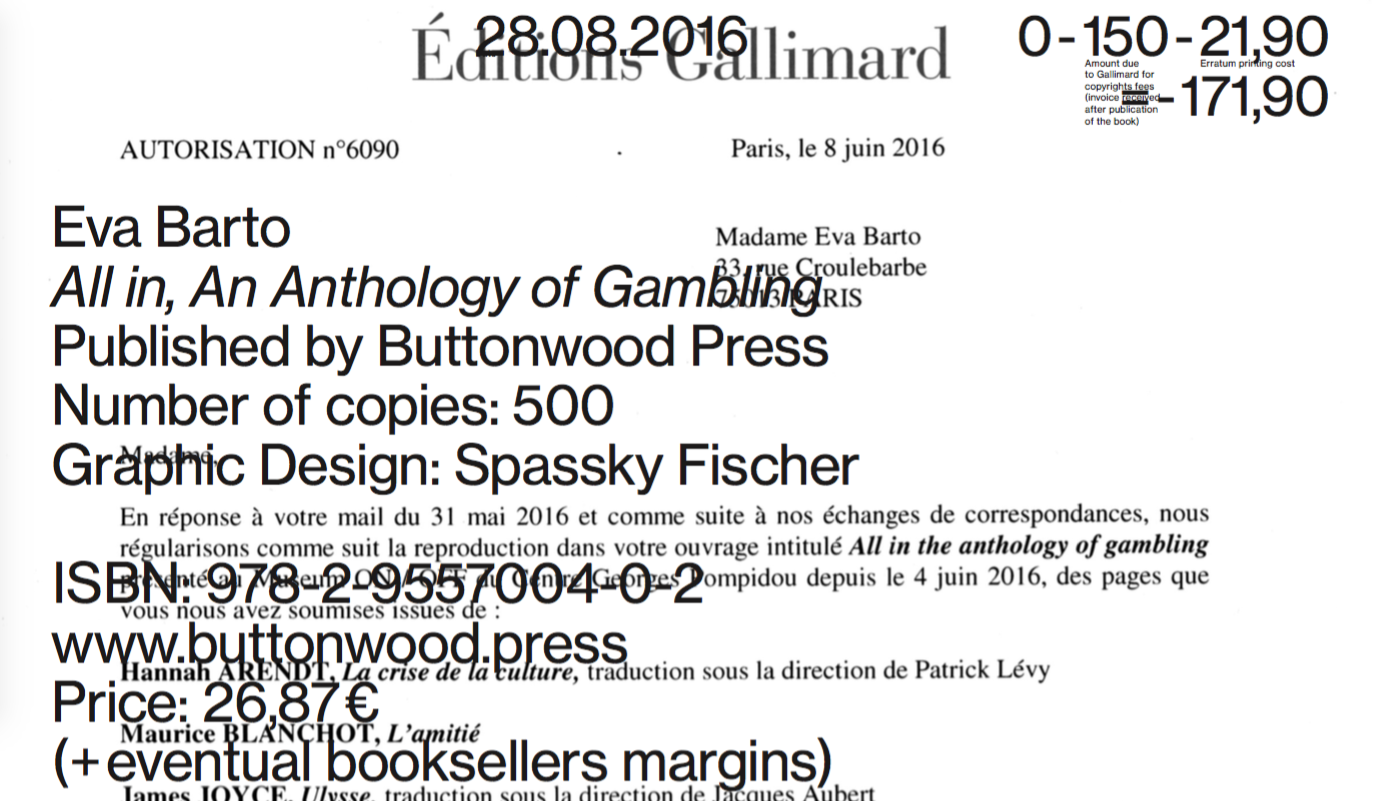

Speculation should not only be understood here in terms of fiction, but above all from the viewpoint of economics, nothing if not Eva Barto’s favourite subject. In an approach inherited from institutional criticism, she grapples with questioning and perverting the logical systems of finance, production and circulation (exchange, traffic, transit) which govern our society, just as they do the art world. By making reference to the stock exchange, alchemy, plagiarism, betting and collectors, she is forever presenting the bait of profit and the thirst for ownership. But speculation is a two-edged game, ushering in the probability of a failure, and the situation turning around. It remains a matter of contingency. It is not surprising, from now on, that the artist gambles in a casino with the money of a patronage grant with a view to producing an edition titled All in, an Anthology of Gambling, retracing the sums wagered, and her wins and losses.

Her recent exhibitions are developed from historical figures possessed by gambling, or the desire to acquire an ultimate knowledge, and fictitious or operative structures, imagined for the occasion. “The Infinite Debt”3 at the Gb Agency gallery drew inspiration from the gold digger and outlaw Cisiai Zyke who, in the 1980s, systematically re-gambled his profits until he found himself in a situation of constant indebtedness. We also discovered in it a shell company suddenly rendered visible, Trust (a cardinal value of the capitalist system, if ever there was), whose identity was overlaid on that of the gallery, in the atmosphere of a shop going out of business, evoking a reality of the economic life of Paris galleries, consisting in renting out their space for Fashion Weeks.

With “:to set property on fire”4 at the Villa Arson, she brings back to the surface the story of Pierre-Joseph Arson, Nice’s first consul, who squandered his fortune with the mathematician Josef Hoëné-Wronski, who was meant to lead him to the secret of the absolute.5 With its deserted stock exchange look, the exhibition gives rise to a line of thinking about finance and the place of the financier, with the artist playing in particular with transparency by, for example, putting online all the expenses attaching to the project. In the Villa Arson’s gardens, she plants a plane tree, a wink at the one beneath which the Buttonwood agreement was signed, which was the origin of the creation of the Wall Street stock exchange, and in it embedded 25 metal hallmarks bearing the initials of the agreement’s various signatories, as well as those of the Villa Arson, in its capacity as an investor.6 This ground-breaking episode in modern economic history also lent its name to the Buttonwood Press publishing house created for the occasion, whose first publication, L’Histoire de grands fourbes et du coupable absolu, reverts, through a cut-up of literary sources, to a purely economic relation which linked Arson and Hoëné-Wronski. The entrance ticket acts as a page marker and the dust jacket as a room plan, whose details make it possible to fully appraise the interactions between the different works of the exhibition and the place in them allotted to language as a catalyst transposing the nature and meaning of the work. The role given to the mediator is also quite special: approaching the visitor, holding a plastic bag, he proposes that he acquire the edition for a symbolic euro, with his function as go-between between the artist and the public turning into that of a businessman or dealer engaged in a transaction.7

In “:to set property on fire”, things thus circulate between exhibition and edition, interior and exterior, reality and fiction, between the spectator and all the available data. As for the omnipresence of references to fire—the phoenix being Arson’s emblem—, this relates to the fire in which big-time gamblers burn their wings, but also to the fire through which a system can end up going up in flames. It is not for nothing, where this title is concerned, that the artist has reproduced on a T-shirt placed in a corner of the exhibition the famous work of Ed Ruscha, Los Angeles County Museum on Fire.

1 Carlo Ginzburg, “Signes, traces, pistes. Racines d’un paradigme de l’indice”, Le Débat, n°6, Paris, Gallimard, 1980, p. 11.

2 Ibid., p. 12.

3 “The Infinite Debt”, gb agency, Paris, from 4 February to 19 March 2016.

4 “:to set property on fire”, Villa Arson, Nice, from 5 June to 29 August 2016, curated by: Eric Mangion.

5 Pierre-Joseph Arson supposedly inspired Balzac for the character of Balthazar Claës, who, in The Quest of the Absolute (1834), led his family to ruin in order to satisfy his devouring passion for alchemy.

6 If the tree is to be presented in another exhibition context, a hallmark will be added to mention the new investor.

7 The edition is meant to be the first point of contact with the spectator for the mediator, who must nevertheless be in a position, in a second phase, to shed light on each one of the works in the show. He also carries with him L’Arnaqueur [The Swindler], a wooden thrower for playing heads or tails with two coins on which he inscribes each book sale.

- From the issue: 79

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Nora Turato, Julien Creuzet, Ismaïl Bahri, Flora Moscovici,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset