Jacqueline de Jong

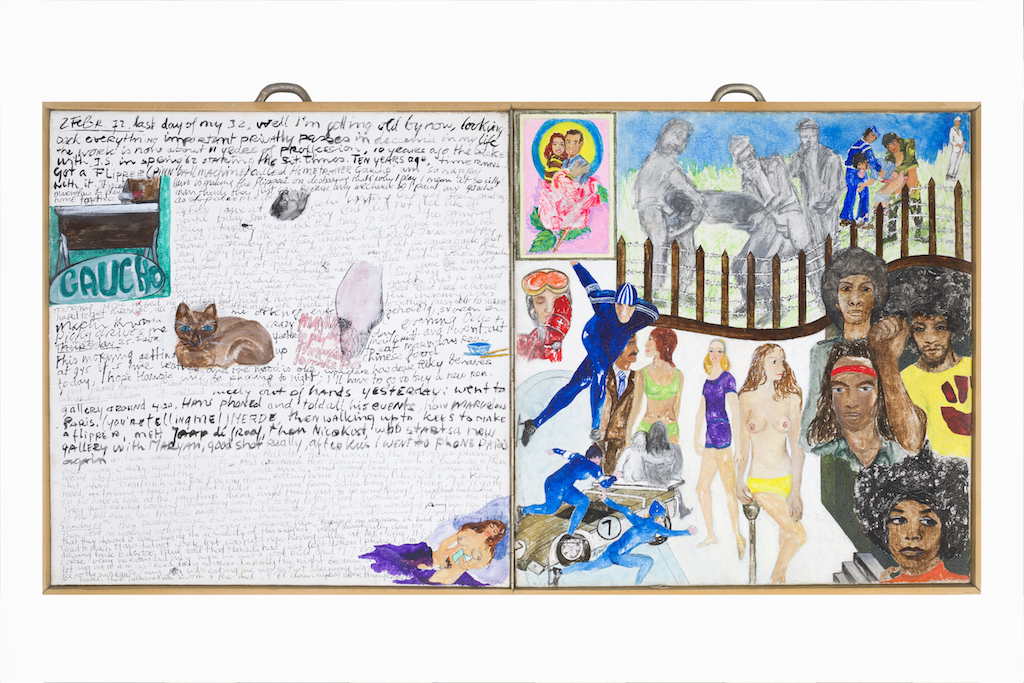

On 2 February 1972, Jacqueline de Jong bought a pinball machine which she nicknamed “Gaucho”. Playing it gave her wonderful and idiotic sensations. She drew it between the lines of the diary which she kept on a suitcase made of two wooden boards. She was about to be 33. “Well, I’m getting old by now, looking back everything important passes in [decades] in my life”. On 24 February, she grumbled about her cat, and said that even if she hadn’t written anything in the last few weeks, she had been painting. At the very bottom of the wooden board, a woman is masturbating while she reads a book, and on the other side of the hinge skaters are hurtling about in the midst of bare-breasted women, orgy scenes, and Black Panthers.1

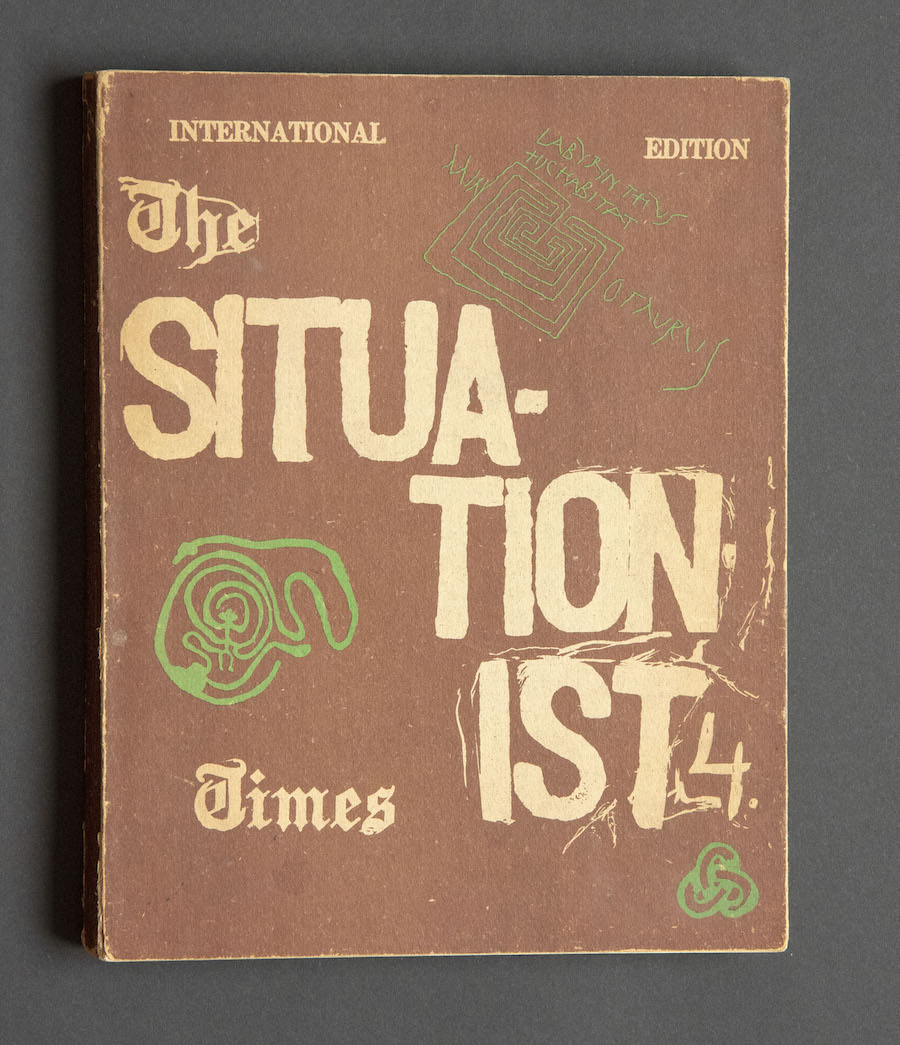

In 2016, Jacqueline de Jong was 77; I am seeing that small painted suitcase and her work for the first time, like other people, no doubt. I realize that if, in February 1972, she had that sensation of growing old, she would nevertheless have to wait quite a few years before seeing her œuvre appreciated, from a critical and institutional viewpoint. As Griselda Pollock has written, women artists born in the first half of the 20th century “only succeeded as dead beauties or old ladies”.2 Yet it is mainly her early years that commentators recall, those years that she was already contemplating with hindsight back in 1972, and which led her from Amsterdam to Paris. Ten years that are described through the alliances she made first with Asger Jorn (who was her companion for ten years), and then Constant Nieuwenhuys and other CoBrA members who introduced her to the Gruppe SPUR and their magazine. Then she rubbed shoulders with Guy Debord and the Situationists, and the New Figuration movement in Paris, encounters which thus ended up enshrining her career within a European history of avant-gardes. These affinities crowd her biography, but the artist, for her part, appears neither in books about CoBrA, nor in reference writings about SPUR. It is incidentally interesting to note that she came up with her most significant contribution to the Situationist movement after having been barred from the Internationale by Guy Debord in 1962. Up until 1967, she thus edited six issues of the magazine The Situationist Times, the only English language publication associated with the movement, trying out a drift among freely associated illustrative motifs, such as an atlas devoted to knots (no3) and one devoted to mazes (no4). She who said that “she had not suffered from that largely male environment”3 only appears very rarely in group photographs. But she created her own photograph, in the form of a collage (1960) in which are featured the faces of the painter Jean Martin, her own face, and those of the Situationists Jorgen Nash and Guy Debord, along with Dieter Kunzelmann’s (SPUR). Despite the visibly urbane aspects of her life, and her many friends and acquaintances, J. de Jong seems to be—to borrow the terminology of Paul B. Preciado—a “phantom limb” 4 of art history, with all the issues today involved by her “rediscovery” by a young generation of gallery owners and critics. Like many 20th century women artists, J. de Jong has been “historicized not through her œuvre, but through her relation with “her” male artists, who were, to boot, “hegemonic”.6 This is illustrated by the number of articles which, caught in this “endless biographical spiral”, forget to see her praxis as a painter, thereby avoiding any confrontation with the complex variety of her work, at times oddly expressionist, at others irritatingly realistic. It is precisely this multifaceted aspect that is highlighted by her recent retrospective show at Les Abattoirs in Toulouse.7 Without calling the contextual importance of those alliances into question, the exhibition enables us to take a closer interest in what the small suitcase has to say: both the artist’s geographical and formal wandering and the intimacy which is created in it through the association of eroticism and violence, the accidental and the grotesque.

Accidental painting

In 1973. J.G. Ballard published Crash!, a novel about two men’s fascination with car crashes, and the sexual arousal they derive from in them, gradually leading them to cause accidents, the better to enjoy them. The destructive “endless variations” of accidents and the “erotic delirium”8 which they give rise to is something Jacqueline de Jong knows about. Back in 1965, she painted Celle qui préfère les voitures as part of a series titled “Accidental Paintings”. A ruddy-faced, toothy, bare-breasted woman is handling with her clumsy fingers what seems to be the wreck of a crashed car, from which a bloody hand emerges. In Ballard’s novel and in this series, dented wheels and bodies cling to one another on one and the same chaotic plane, which is “dense and flat”.9 What amuses the artist is the drama at work, and what different modes of representation, what twisted compositions, its contained tension can create. The damaged figures caused by road accidents were thus followed, in the early 1980s, by the Série Noire, a set of pictures inspired by a thriller literature full of murder scenes and grey raincoats. It is in an alternately pop and narrative figuration-like vein that J. de Jong then explores the stiff lines of victims either prone or hanging by a foot (QuasyModo and Queen Kong, 1981), and perspectives overarching slouched bodies (30 maart 1981). But it is not just the question of drama that emerges from the “accidental” terminology she used in the 1960s. Chance also criss-crosses her œuvre, not as an active principle (although, for the autodidact she is, the shift from one pictorial style to another is seen as a ‘challenge’ which she tosses out, with all that that implies in terms of uncertainty and beginner’s luck), but as a motif, or situation. So games have a special presence in her work, especially in the Billards series. Like murder scenes, the challenge is situated in the intent of the framing, serried on the green table, or constrained by the angle formed by the cue and the arm holding it. The tension of the presentation resides less in the outcome of the game than in the claimed sexual interplay which, once again, passes by way of an object, the provocation of chance. What are the characters in Crash! doing, if not, as in a 1978 canvas, grabbing the devil by the tail?

“Potato balls”

If the accident is an incentive for painting, it is also a lens for manhandling the human body, dislocating it, and turning it inside out until it is unrecognizable or ambivalent. Jacqueline de Jong seems to have experimented with this crisis of human outlines with some mischief over the decades. Thus it is that a grotesque tone and at times terrifyingly ugly absurdity emerge from the painted works on view at Les Abattoirs in Toulouse. In the 1980s, she produced a large format series in which half-human half-animal figures have fangs which protrude from their mouths, and sharp feet, sometimes with claws, sometimes with toes. The artist presents them in huge compositions where they are so entangled that it is hard to know whether they are devouring or embracing each other (Chemin Perdu de la Chasse Frustrée). Other physical changes are at work in the large painted tarpaulin that she produced in 1992, The Backside of Existence. On either side of the floating surface, winged creatures and figures with exaggerated postures are caught in a dynamic of attraction and repulsion which seems to distort them even more. The scene, which has been likened to an apocalyptic struggle between good and evil, might be part of a tradition of the grotesque incarnated by the mediaeval Flemish painters Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. If you like take a close look at The Fall of the Rebel Angels (1562), all that seems to exist in J. de Jong’s work is monstrous and hybrid angels, those who, at the bottom of the picture, show their entrails and their tongues.

The experiments undertaken by the artist over the last few years with potatoes extend the question of the grotesque and human deformation within the plant kingdom. Collecting tubers germinated in the darkness of her cellar, she involves them like so many characters in a series of photographs transferred to canvases (Potato Blues) and a book, a wink at the Situationists, Psychogéographie des pommes de terre (2017). She is amused by the vegetable’s shrivelling and what it grows by way of protuberances, likening them to heads and “potato balls”. This expression, with which she covers certain images, reminds us that J. de Jong’s pictorial grotesque is often redoubled by the use of a thoroughly deformed language. So the titles of her works only rarely seek to describe them, they tend rather to have fun with false leads and clumsy spelling. The artist is a polygot and her pictures, from Salo et les Salopards (1966) to Tournevicieux cosmonaute (1967), express as much in an oddly hybrid way.

In 2003, to mark Jacqueline de Jong’s first retrospective, the CoBrA Museum of Modern Art described the artist as a secret agent (“Undercover in de kunst”). If this title ill-advisedly fictionalized the reasons why people had not known about her art hitherto, it nevertheless describes the ongoing duplicity in which J. de Jong operates. And this “flipside of existence” which she criss-crosses could well be the grotesque lining of the reality in which animals, potatoes, human beings and machines all merge together, where time can be suddenly dented, where form is always brought back into play, like a pinball.

1 Op het land waar het leven zoet is, 1972, was shown by the Château Shatto gallery at Paris Internationale in 2016. In it we can read “2 Feb. 1972: last day of my 32, well I’m getting old by now, looking back everything important privatly passes in deccenia (sic) in my life”.

2 “Women artists have, until the YBA phenomenon, done well as only dead beauties or old ladies.” Griselda Pollock, “Old Bones and Cocktail Dresses: Louise Bourgeois and the Question of Age”, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 22, No. 2, Louise Bourgeois (1999), p. 73-100.

3 Telephone interview with the artist, January 2019.

4 Paul B. Preciado, “ The phantom limb: Carol Rama and the history of art”, The Passion According to Carol Rama, MAMVP / MACBA, 2015.

5 Ibid., p. 20., P. B. Preciado of course emphasizes the colonial history of the notion of discovery which we must keep our distance from: discovering is “naming with the language of power”.

6 Ibid., p. 22

7 From 28 September 2018 to 13 January 2019. This was her first retrospective in France.

8 J. G. Ballard, Crash !, 1973.

9 David Cronenberg on his first impression of Crash ! which he adapted as a film in 1996 https://www.lesinrocks.com/1996/07/17/cinema/actualite-cinema/entretien-david-cronenberg-crash-0796-11233431/

Image on top: The Backside of the Existence, 1992. Courtesy J. de Jong; Château Shatto, Los Angeles.

- From the issue: 89

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Merlin Carpenter - "What’s so elastic about you ?", Corentin Canesson, Celia Hempton, Madison Bycroft, Charles Atlas,

Related articles

Céleste Richard Zimmermann

by Philippe Szechter

Julien Creuzet

by Andréanne Béguin

Anne Le Troter

by Camille Velluet