The Absent Museum

Wiels, Brussels, 20.04—18.08.2017

Everything here gravitates around a museum which does not exist. We have already known museums that are ghostlike, impossible to find, imaginary, odd, or questioning institutions. A case in point: there was Daniel Buren’s Le Musée qui n’existait at the Centre Pompidou in 2002, with hidden works; further back in time, there was Marcel Broodthaers’s fictitious and parodic museum of the Département des Aigles, created in 1968; and even earlier, the infinite collection of André Malraux’s Musée imaginaire, an essay penned in 1947. But unlike those museums, the exhibition at the Wiels talks about an absent museum, i.e. a missing museum: a museum which we miss.

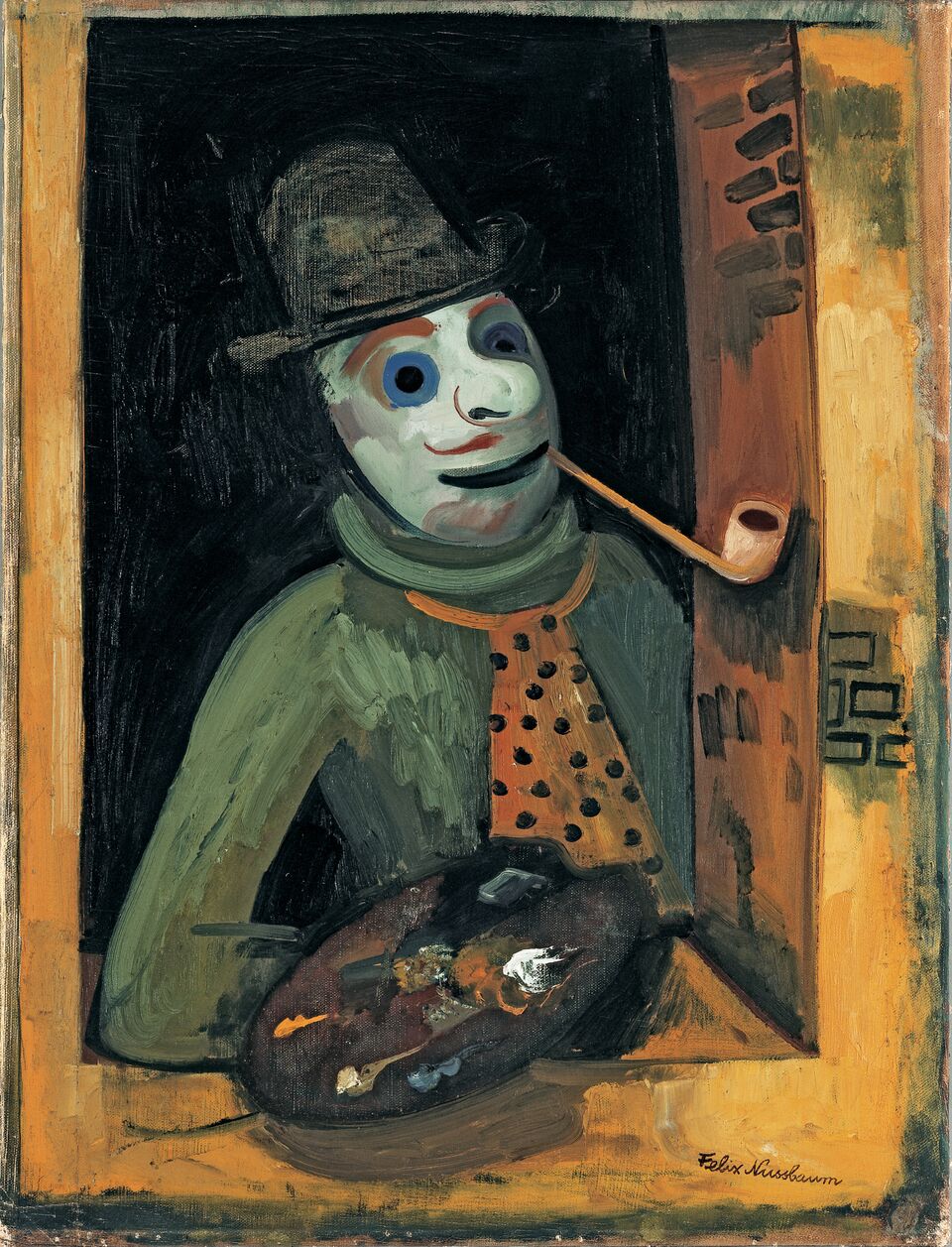

Felix Nussbaum, Maler mit Maske, c. 1935. Oil on canvas, 62 × 47.5 cm. Private collection. © Felix-Nussbaum-Haus Osnabrück.

In Brussels, there is no museum of modern and contemporary art, unlike in most major capitals and metropolises. Thus presented, the fact is not, if the truth be told, alarming: why should every large city have its museum of recent art? To what end? The question is raised all the more because the world’s great museums all end up looking like one another, with their successions of artists arranged in movements and periods. No, the fact to be retained is that in Brussels, as Europe’s capital, there is no museum of modern and contemporary art. Installed in an old Art deco-style industrial brewery—a five-storey building constructed in the early 1930s—the Wiels is the reference in terms of contemporary art in Brussels and, with “The Absent Museum”, it sees itself becoming this missing European museum. But this is well removed from the hagiographical and conventional arguments in favour of Europe. Like a think tank, the exhibition helps us rather to understand how we, Europeans, are linked through an aesthetic, social, political history, at times positive, at others negative, but undeniable. In a nutshell, the exhibition goes beyond the field of artistic knowledge and confronts us with the role and political commitment of a museum, today, in Europe.

If there is an unavoidable issue for such a museum, it is indeed that of the place of European culture in the world as it has evolved over the past few years, thanks to post-colonial awareness. How is the end of western supremacy translated in art history and, consequently, in the choice of works to be shown? In the exhibition’s entrance, a huge banner by Thomas Hirschhorn broaches the subject starting with the relation to the other. An inscription simply declares that in order to construct together, we must presuppose an equality between oneself and the other, a principle that must thus also be applied in the art world. In one of the first rooms, an installation by the Colombian artist Oscar Murillo, Human Resources (2016), heads in the same direction. On wooden tiers, characters made of papier mâché and cloth, on a human scale, seem to be waiting for us, observing us, and even asking us to account for ourselves. They are clad in work clothes, workers, farm labourers, exploited, and looking as if they have come to arrest us. Right beside them, a set of three oils on canvas by Luc Tuymans titled Doha (2016), depicts a museum in the capital of Qatar, where the artist had been invited. Like a museum within a museum, Middle East versus Europe, these paintings conjure up the determined policies of the Arab Emirates in cultural matters—here Qatar, but one thinks, too, of the island of museums in Abu Dhabi—which, rather than giving rise to sarcasm, should challenge us: who is wagering the most on culture?

The exhibition also proposes more defined themes such as the shared legacy of the war years. A wall text in Flemish, English and French by Francis Alÿs, 1943 (2017), poetically sums up the situation, but just as effectively. Through a repetitive form, it spells out what the great European artists were doing in 1943. It begins thus: “I am thinking of Morandi painting at the top of a hill surrounded by fascism”. Immediately afterwards: “I’m thinking of Picabia finding inspiration in pornographic magazines on the French Riviera”. And again: “I’m thinking of Cartier-Bresson escaping from a German work camp”, and: “I’m thinking of Félix Nussbaum hiding from his neighbours in Etterbeek.” Presented in the same room as one or two paintings by this German artist who was deported to a camp after a stay in Brussels, Alÿs’s melancholic rearward gaze assumes its full meaning. We are all heirs of those dark years. Lastly, certain works deal in particular with Belgian history and art, but are perceived here in a metonymic relation to Europe, with wit added.

Jef Geys, Gleichheit, Fraternité, Vrijheid, 1986. Martin Kippenberger, Untitled, 1988 © Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Gisela Capitain, Cologne. Photo: Kristien Daem.

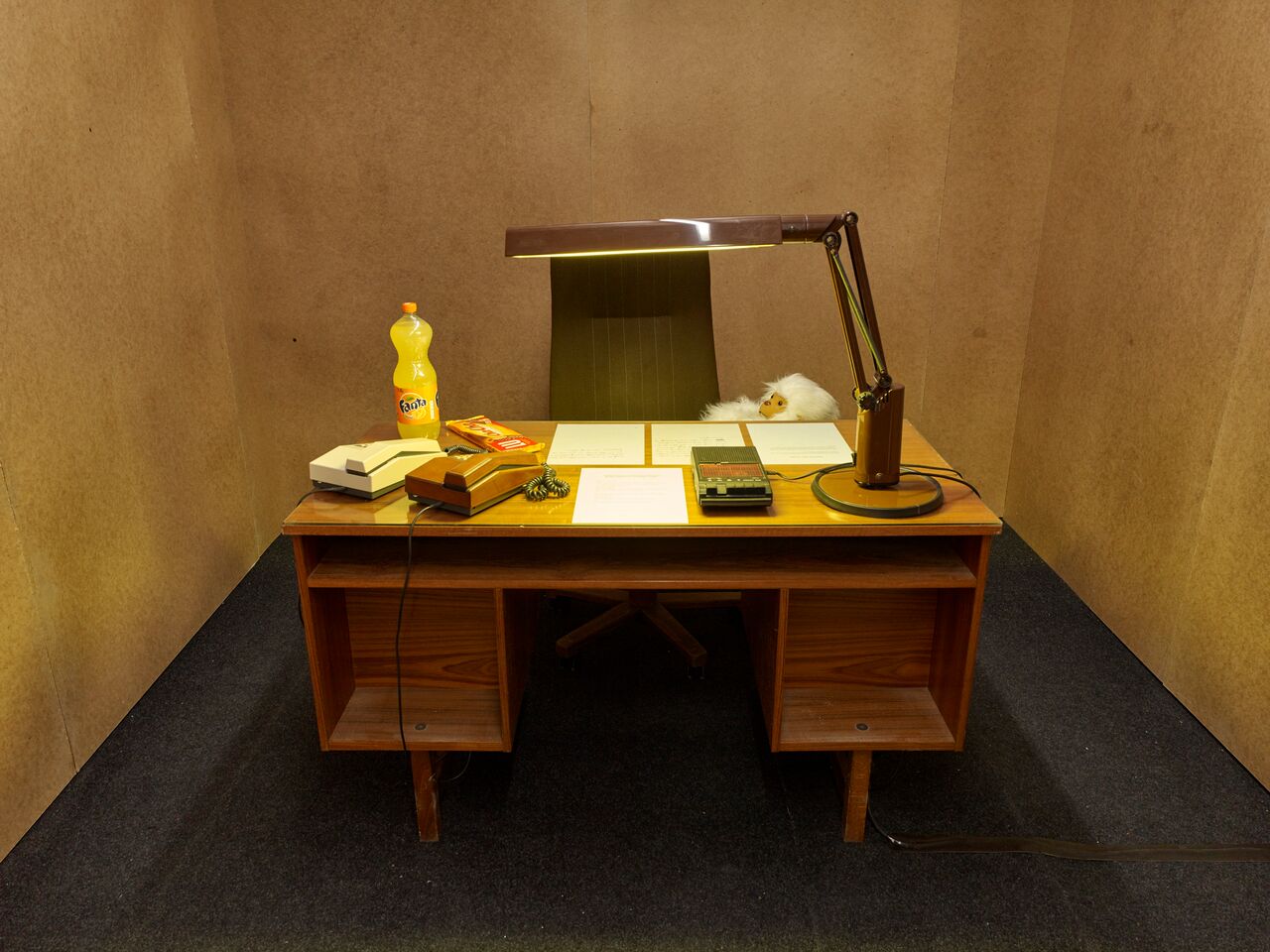

So it is with Jef Geys’s out-of-service door of 1986, on which the word “Fraternity” is written in German, French and Flemish. Direct and irrefutable, it refers us to our own inability to apply the bases of our political creeds. Another example, in the basement of Le Métropole, an erstwhile administrative building in the now disused brewery where the exhibition is continued (and likewise alongside, in Le Brass, a place where beer used to be colled), the twosome Jos de Gruyter & Harald Thys has installed a work of political fiction, Kaiser Ro (1993). Photos, videos, objects and documents are brought together as in a history museum, retracing the brief dictatorship of the Emperor Ro, a distant cousin of king Ubu, who allegedly came to Belgium in 1990. After a coup d’état, he spread terror in the land, in particular by entrusting a torture centre to a sports teacher and creating so-called formidable fantasy weapons. Phony historical period, phony relics, phony museum, this work uses black humour to deal with an anxiety that is essentially thoroughly real, that of letting Europe topple into the hands of authoritarian, not to say fascist-oriented, regimes, causing us to re-plunge into the darkest periods of the continent’s history, unless we beware.

Harald Thys & Jos De Gruyter, Keizer Ro: Het verslag van een staatsgreep in onze gewesten, 1993. Courtesy Harald Thys & Jos De Gruyter. Photo : Kristien Daem.

(Image on top: Oscar Murillo, Human Resources, 2016. 8780 × 9830 cm. (Deetail). View of the exhibition «Flying Moths»,

Condo, Carlos/Ishikawa London. Courtesy Oscar Murillo ; Carlos/Ishikawa London.)

- From the issue: 82

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Alias at M Museum, Leuven, Jérôme Zonder at Casino Luxembourg, Nathaniel Mellors, ELNINO76, Yannick Ganseman*,

Related articles

Streaming from our eyes

by Gabriela Anco

Don’t Take It Too Seriously

by Patrice Joly

Déborah Bron & Camille Sevez

by Gabriela Anco