Yoga for the institutions

Isabelle Alfonsi is co-director of the Marcelle Alix gallery, which she founded seven years ago with Cecilia Becanovic; she is also an associate researcher at the Dijon School of Fine Arts, and is currently preparing a book on the genealogies of queer contemporary art. Emilie Renard has been running La Galerie art centre at Noisy-le-Sec since 2013. Both are deeply involved with the question of feminism as crystallizing the issues of commitment within contemporary art. A commitment which they see not only from the angle of the lack of representativity—which, in their view, is simplistic—but in a wider way, by incidentally entertaining a line of thinking on seemingly immovable stances in the art world. Because one line of thinking leads to another, this interview which aimed at comparing activities whose goals, on the face of it, differ—the market, public service—, leads to a re-visitation of practical methods and models with regard to their structures, the idea being, for example, to re-think fragmented exhibition sequences for the art centre, and lean towards something much more organic for the gallery—and thus reinvent professions and trades which we would be wrong to think of as immutable. QED.

You are both very busy people, extremely involved in your respective areas, which makes you attentive observers of the art world and its development: don’t you have the feeling that things have shifted a great deal in art circles over the past twenty years or so? I’m thinking more particularly of the place of women, whom we are now seeing regularly at the head of institutions, art centres, and galleries, even if they are still in a minority at the head of major institutions, even when these positions are perhaps less positions of ‘power’ than they have been in the past. As for artists, aren’t we witnessing nothing less than a boom in the presence of women artists in galleries and art centres, even if, here again, we need to qualify such a statement?

It seems to us that the question you’re raising is part of what we’ve been hearing for ages about feminist commitment: you get the impression that the situation is improving and that we’re minimizing the need to stay alert and mobilized (a way of discouraging those who might be attracted by such an involvement). The fact is that the qualifications you introduce into your idea are quite right: the glass ceiling is still very present, when you consider the highest placed jobs in the cultural sector. The ‘boom’ impression about the presence of women must not only be associated with a question of power but above all with a change of economic context: there is much less money available in culture than twenty years ago (and culture has lost all strategic importance for politicians); so it’s not nearly as hard to ‘fob off’ certain management jobs to women. As a result, they are the first to be recruited in contemporary art centres where things are quite difficult. We can’t sideline the hypothesis that, in such a context, the recruitment of these women is being made on the basis of a certain number of preconceived ideas connected with the way in which the difference between men and women is still operating: women are more organized, they keep more closely to their budgets (they are ‘good pupils’), and they will put up less opposition in the event of disagreements (they are ‘soft’). What’s more, your question invites another precision: the challenge of representativity is not the only one to be taken into account. Needless to say, as the feminist historian Griselda Pollock underscores, we need “woman artists to like, and we need them to find a space and a cultural identification for ourselves, a way of expressing ourselves—in order to produce an alternative to the present-day systems which exploit sexual differentness to make a denial of our humanity, our creativity and our security”. It’s important that female art students today know that you can be a woman and an artist. For the time being, these models are not always obvious. For some, ‘carving out a career’ involves personal choices which are not required for men, and this is still a brake for many women. So we must carry on the struggle so that more women have access to visibility, and so that they feel less hobbled than men.

But we can’t limit ourselves to this ‘quantitative’ approach to representation which is broadly that of a feminism with reactionary tendencies. Marine le Pen calls herself a feminist, to a certain degree, doesn’t she? If she’s elected, we’ll be able to say that she’s the first woman president of the Republic: so you can see the limit of this approach! Our struggles do not just have to do with representation. If we want to improve the situation in art circles which are still mainly a white boys’ club (and thus so removed from the world), we must also bring about a change of method in the way we work, the way we address each other, the way we see our programmes. Being feminist is not just counting the number of women present here and there, it’s also questioning the relations of power which underpin our ways of operating, personal and professional alike, still largely based on ideologies of differentness, be it sexual, racist or to do with physical and mental validity. This is what will enable us to act in such a way that we can live in a world that resembles us.

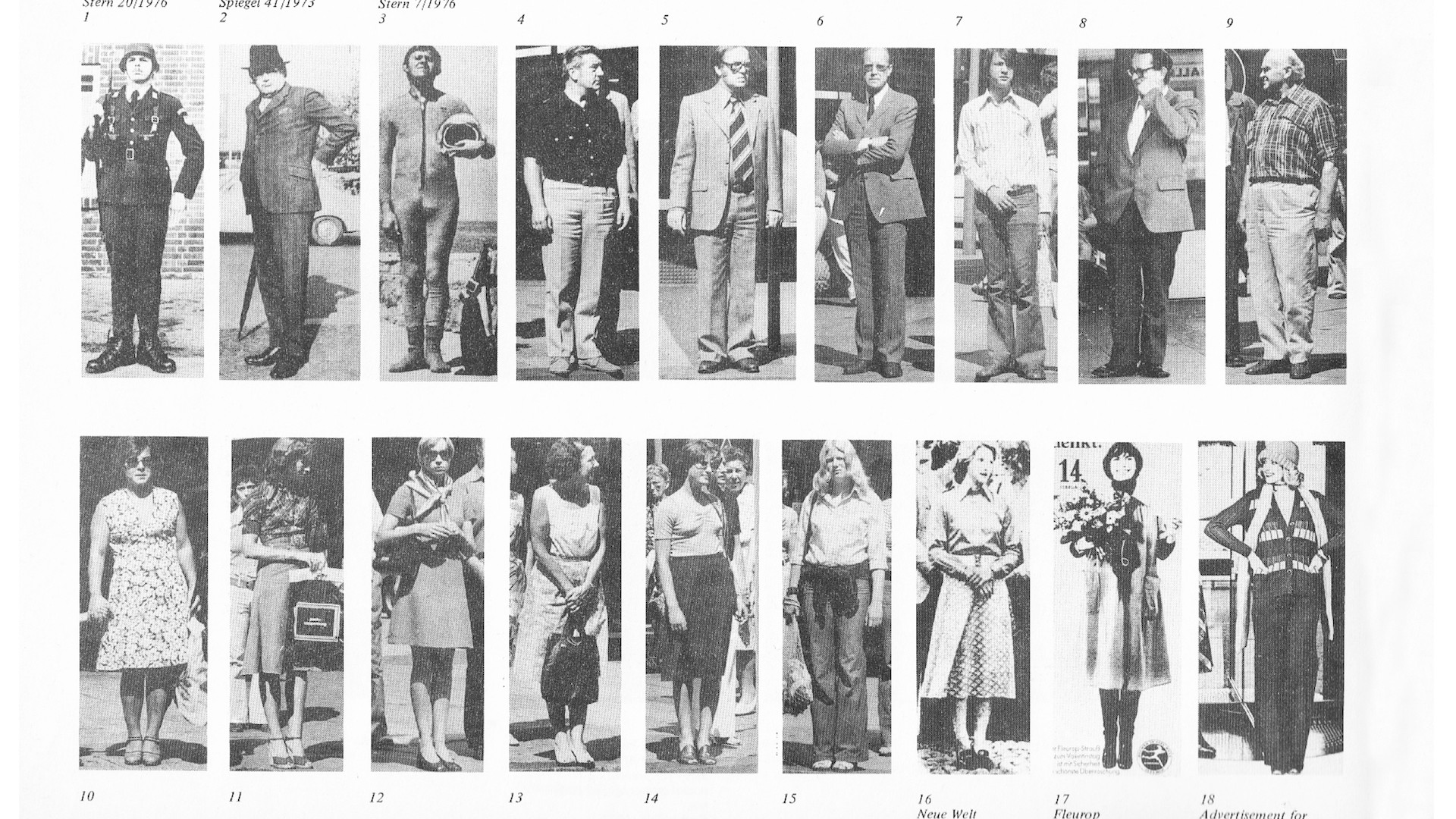

Toutes les images :

Marianne Wex, «Female» and «Male» Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures, 1972-77. Detail. Photo : Felix Grünschloss

It’s clear that the female issue and the issue of the situation of women crystallize a certain number of dysfunctions (to wallow in euphemism) within the art world. This also leads to a question about your respective programmes: be it in an art centre or a gallery, does this matter of representativity have a direct influence on your choices of what to programme?

Our feminist commitment is obviously visible in our respective programmes because we are working, evolving and talking about things with a large number of people who share our thinking, whether they are artists, authors, critics, curators, philosophers, and so on. So these intellectual affinities can be seen in the exhibition terrain where we work with women, people from minority groups, but not exclusively. It seems important to us to specify that a programme isn’t limited to a list of artists, there is also the matter of a working method within it. A feminist approach—of an art centre or a gallery or any other institution—involves an overall way of thinking about these organizations; this way of thinking applies to methods of governance, to the social roles of our professions, to working conditions, to the economy of art, and artists, and to how to address the public (in terms of mediation and communication). This kind of feminism links up in many ways with social and political struggles that have been waged for a long time now, and it can thus be seen in many parts of our organizations other than the terrain of exhibitions and art. For us, representing artists who deal with these political issues necessarily means constructing exhibition formats and ways of operating which have an effect on our organizations and resist the present-day conditioning of the art world and of the world,—for example the ever faster pace of exhibitions, especially in galleries, and the procession of events which punctuate them, especially in art centres, are part of a phenomenon of ‘event creation’ in art, which we can counter with different paces. This coherence between programming and governance is probably what may set us apart from a catching-up effect in certain institutions which are realizing (but it’s never too late) to what degree they have managed to ignore women and minorities in their programmes, without this having any more fundamental effect on how they operate and on their work reflexes. Once again, it is not just a matter of ‘representing’ and staying with the image and quota, but one of questioning ourselves about the structures of domination which undergird the operation, in our case, of a gallery and an art centre.

What’s more, it also seems to me that the politicization introduced by the female issue—emblematic of discriminatory situations—may also clash with a market logic which does not especially involve bringing such positions to the fore, because it is mainly guided by a liberal way of thinking and speculative principles which may be regarded by some as the source of or factor responsible for these inequalities and dysfunctions. This, needless to add, raises the issue of the responsibility of art and artists, their possible ‘engagement’, along with that of people involved with art, such as yourselves. Do you think that, in this regard, the situation has markedly evolved since the 1990s, that the seemingly immoveable gap between art and politics has once and for all won the battle, and that, to don the mantle of being ‘bankable’, art must do away with all the rough edges of protest which are a bit too conspicuous?

You are certainly aware that one of the major features of the neo-liberal capitalist system which governs us is to end up by retrieving within it everything that was first created on its edges, and pass it through the mill of commercialization (on the whole it succeeds). Nothing remains unsellable for very long (what you call the ‘political’ art of today, which is shunned by the market, becomes the ‘bankable’ art of tomorrow)… So women are starting to be in vogue, because everyone is realizing that many of them have worked in the shadows and put together colossal bodies of work, and that there are accordingly whole swathes of the history of art which are still little visited. Some studios are crammed with works which nobody wanted for 40 years—what a windfall! These are new stocks to be mined for galleries, new heart-throbs for museums, new events to be created! Everyone is looking for their ‘woman artist’ to be (re-)discovered, but it’s better to choose her very elderly so that she longer poses any threat, which is to say that she doesn’t have the bad taste to want, in addition, to make claims or protest, talk about things which irk, get away from the context, or just quite simply exist a little bit too much. When Carol Rama received the Lion d’Or at the 2003 Venice Biennale, she said that it was “too late”. She was 85. She died before she was able to visit the retrospective of her work that was held at the Paris Museum of Modern Art in 2015.

Women and minority people are often punished for having wanted to express too forthrightly a particular viewpoint, which does not seem ‘universal’ to the majority. This ‘engagement’ you talk about is the desire to make an unusual viewpoint visible: all art is political as soon as you veer away from the system in which it is born, in which it does not blend in with the mass. What we are trying to suggest, especially in the way we talk about our respective activities, is that nobody talks from a neutral place, from a position that “overflies, from nowhere, from simplicity”, to paraphrase Donna Haraway. This probably doesn’t make us very ‘bankable’ for the time being, but it makes us happy, and that’s already something.

In a text you published on Le Monde.fr1, you ask yourselves the question of knowing what the word ‘gallerist’ means to people. I would like to ask you the same question: what do you think the words ‘gallerist’ and ‘art centre director’ mean for people in 2016?

We’re not particularly worried about the ordinary representations of our professions, but we want to incarnate these roles in a way that’s personal, but also partial and open to other functions. For us it’s more a question of doing things in such a way that our functions include many other aspects of who we are, and to be probing and militant, too, for example. For us, being a gallerist or an art centre director is above all having positions from which we can act within very flexible organizations where social roles can be redefined. In the end, we benefit from the relatively small size of a gallery or the relative weakness of an art centre like the one at Noisy-le-Sec, because these structures can evolve forever, nothing in them is played out far ahead, and because they enable us to construct precise working relations with artists. With a small number of artists, a gallery develops long and hands-on relations, while an art centre is meant to renew itself by moving from one exhibition to the next, and gropingly building a history made up of many moments all added together.

At La Galerie in Noisy-le-Sec, we’re trying to inject a well-paced programme which constructs different forms of continuity. It’s a project that runs counter to the idea to do with breaks and discontinuities, which divide and carve up history, but also the art centre’s spaces and its different briefs. We’re trying to link everything to a common project, and create bonds and even shifts in the roles of those who form it—the teams, the artists and the public. For example, works can stay from one exhibition to the next, and even ‘linger’ for several years, because they are also functional (a curtain, stands and pedestals, benches…), and artists who were in residence can go on being supported by La Galerie… Constructing slow cycles, accepting to let go, and not control everything, giving artists and teams the chance to act in different parts of the art centre, this is the whole challenge of the exhibition now on view which we have devised together with Vanessa Desclaux: it’ll last for one year, and develops throughout the entire art centre, it’s a bit like a technique which makes current categories more flexible, a kind of yoga practiced on the institution. Marcelle Alix operates a bit in the same way: we’re not really trying to ‘bring things off’ or make a splash, or develop strategies, but rather extending the work time with the artists, constructing things slowly and organically, so that they seem right to us, with Cecila Becanovic. We try not to do anything violent to ourselves, and bear in mind what we like about the ‘gallery tool’. Perhaps when it seems no longer functional and when we can no longer conduct things the way we feel like because the conditions around us have changed, perhaps then we’ll change tools. We’re less and less attached to the fact that the gallery should make gallerists of us; what attaches us to the gallery is the fact that it’s the best tool for offering the conditions of our freedom.

1 http://elles-defient-le-temps.lemonde.fr/art/marcelle-alix-la-galerie-defricheuse_a-20-54.html

- From the issue: 80

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Claire Le Restif, Bouchra Khalili, Sophie Legrandjacques, Sophie Lévy, Christine Macel,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton