New Enumerations

New Enumerations

Enumeration has strange powers. It feeds into that erudite (and slightly suspicious) passion for learned accumulation: “this reference, that reference, that reference…”. In a more refreshing way, it awakens the memory when an Oulipian constraint brings back places from a forgotten youth, in a progressive reconstitution: “a pillow, a bedroom, the sounds of a schoolyard, an impasse, the weather on that day…”. When it comes to our monetisable personal information, it indicates characteristics of an “identity” which is becoming ever more atomised: “age, gender, habits, likes and dislikes…”, not to mention (irrational) biases which guide our clicks. What is the point of these verbal enumerations, as varied as they may be? The much-desired totality of everything belonging to us? Perhaps. A steady stream of new sources of enjoyment? Not exactly. These enumerations may not be seeking anything specific, since they mainly exist within the continuity of reporting, barely keeping under wraps the anxiety arising from the fear that something might escape this encyclopedic aim, or quite simply, that this act of listing might come to an end.

There are other ways of enumerating besides verbally; there is also object-based enumeration, not only by addition but through detachment, through constellations, multi-directionally. This type of enumeration is more difficult to put in order, and can be seen in recent models of the collection of recycling and in new reading technologies. It goes beyond the linearity of a phrase, reaching deeper, not necessarily in a less anxious way, but it allows us to access time differently, often soliciting reactions of incredulity; the world is really quite predictable in its attachment to a fear of the end. Nevertheless, we must stand in contradiction to this world. Other worlds must become embedded in this world (by celebrating the 100th anniversary of the publication of Ulysses, for example), and, moreover, other measures of time must be introduced, therefore releasing a bit of hope, in the midst of “time getting away from us and dragging us along with it” (Boileau).

Ecological Depositions

Who forgot to clean up this time? In the exhibition Sporal at Palais de Tokyo, it is no longer Daniel (Spoerri), but Mimosa (Échard) whose “painting traps” are spread around creating complications: things getting caught up in mosquito nets, specifically, or immerged in toad saliva, nothing too offensive, really; more tangy than sour. Among the ingredients for this magic potion are: “plastic balls, silk cord, rubber bands, false pistils, blue pea flowers (Clitoria ternatea), gelcaps, kapok, or silk cotton, wool, paper lanterns, mosquito nets, cherry stones, plastic eggs, glass beads…”.

In other words: “I want to put practically everything in, to saturate, but through transparency” (Virginia Woolf). Sometimes beaded necklaces tumble downward like a stream of fluorescent glue frozen underneath a star. By falling it indicates a small maelstrom forever frozen at the bottom of a washbasin into which it was decided to throw a lot of random stuff on an impulse, just to see what happens. This form of half-way believing in uncertain recipes, magical for no reason, is an accompaniment to an ecology of art (a child-like one?), one which would reinvent a tact and an attention toward what is being put forth, despite an apparent exhaustion; an inventive attention, which amazes and even surpasses the act, sneaking up on it.

How to create something out of next to nothing—not just something, but something incredible—by solemnly mimicking the ceremonial enumeration of ingredients found in an old spell book which does not exist; partially because the act of writing can no longer be distinguished from a work in progress. And so there would be an ecology of art in the style of an ecology of storytelling which expands our world as mediated by epic tales or fantasy novels, opening up an entire archaic avant-world, of dragons and magicians, in which ours would be nothing but the shrunken realistic one, soulless and dedicated to economic instrumentalisation. In Valet Noir (Black Valet) – Towards an ecology of storytelling (Corti edition), Jean-Christophe Cavallin discusses fantastic and mythical narratives which fulfill the function of “augmenting our context” in order to ensure the survival of a world of powers which have disappeared or forgotten cyclical temporalities, which have recently made a comeback in the midst of fears of ecological disaster. Which is not to say that these magical or terrifying legends should be believed, simply that they have a potential to create a feeling of openness leading to new directions in thought, as well as for the imagination. They also create new possibilities for the expression of fears and promises which are worthy of collective experience through narration. A contextual narration, dating from another time, one we cannot quite grasp; whose equivalent in painting would be the power to enumerate, between two traditional elements, the existence of species which have yet to be identified, juxtaposing natural with supernatural, real with surreal, the outdated with what has yet to materialise. And yet, with the awakening of an object-based imaginative realm comes a developing sense of concrete practicality; a careful, imaginative way of approaching things (archaic and futuristic, child-like and ageless) that are innocently laying about, with no particular meaning in and of themselves, yet elicit the desire to create meaning for a fleeting moment, the time it takes to tell a story, or to reinvent something which already exists, a bit hidden but sufficiently iridescent to draw attention to themselves. E.g. the freshly-made path of a snail in the grass, an old plastic toy from the 1990s beneath a coating of dust. What will become of these things in your larger-than-this-world story? What desires will they serve, what will be harvested through them?

A bit further on, on the floor inside the exhibition “Reclaim the Earth”, shards of broken glass bottles appear, having become porcelain shells filled with an impossible fluorescent colour, (Kate Newby), or plants made of bronze spread out on a sheet (Abbas Akhavan). Having fallen there in silent unison, they attract the gaze in a communion of sorts. The aforementioned plants evoke the consequences—ecological among other types—of the war in Iraq initiated in 2003 and helmed by American forces (George W. Bush has recently condemned the flagrant illegitimacy of this war in an incredible Freudian slip, where he confused Ukraine with Iraq, lightheartedly excusing himself with an “I’m 75!”). Perhaps in every collection there is recollection, or reverence, in memory of other worlds, other less fatal patterns, other ways of functioning that would have resulted in a completely different outcome for these already fossilised debris. In addition, in every collection there is a Deposition (let us believe in legends for once), and the phosphorescent possibility of a Resurrection. For example, in a children’s game when one is open to the diversity of the surrounding world, to places and times yet to come.

Scroll Vertigo

Scrolling up on a mobile screen is an archeology of the personal. Just like with a text, we go back in time, only without the hiccup of the turn of the page slowing us down, in a book where we have skipped a passage or the complicated name of one in a long list of characters. In this case, scrolling is nothing but pure, continuous elevation, an inversed archeology, that rises up instead of digging down into the deep. Only a thumb is necessary to enumerate (recount, rehash) series of received and sent messages, towards whatever is most interesting or what was misunderstood at the time “Oh, hmm, so it turns out…”. A checking that is disappointing, comforting, inspiring, or worse: happy. And sometimes, a few years out: stupefying. Because we read (felt, lived, got mixed-up) differently then than we do now. A disconnect smack in the middle of introspection, only not while reading a journal, but when faced with our own reaction to someone else, now unknown to us, as well.

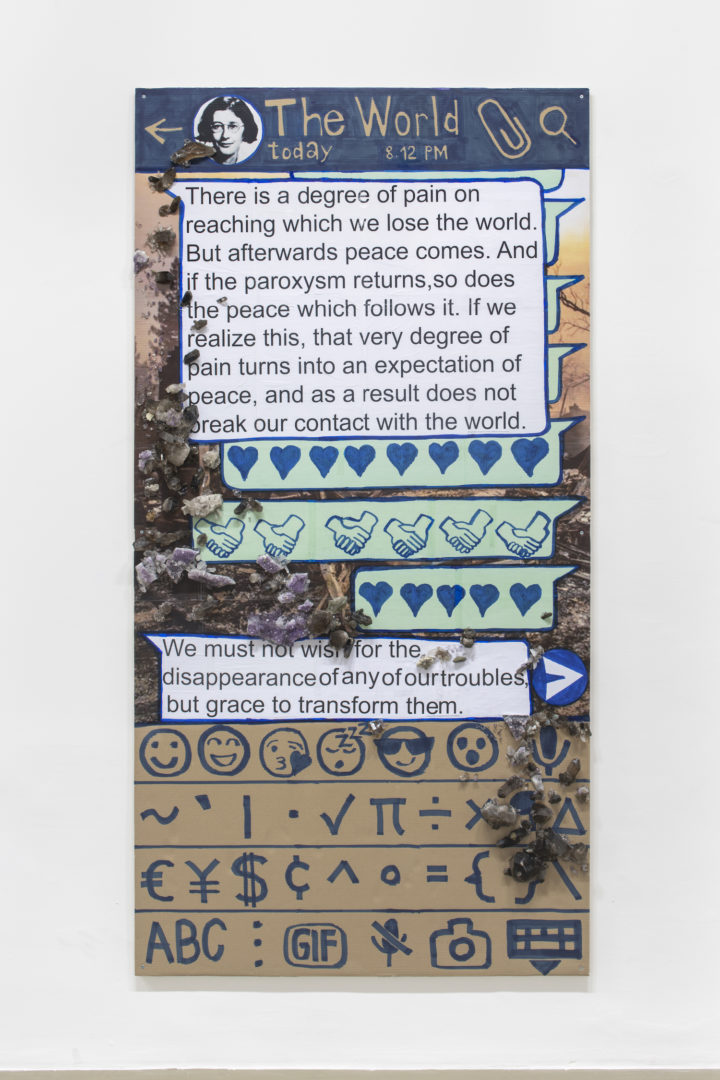

And so instant messaging is a form of personal archeology, but also a geology of a much larger historical scale. For instance, what would happen if we were to scroll all the way back to before instant messaging technology was invented (unimaginable for the younger generations), and a message were to appear, nonetheless—a fantastical tale suddenly becomes unsettling. In his Chats-posters (2020), Thomas Hirschhorn places a few crystals on the surface of Whatsapp chatscreen enlargements, glued onto cardboard, fake, humble, child-like, Brechtian. As we move backward through the geological strata of time, we see a fragment of a message from Simone Weil (1909-1943), for example: “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” The letter addressed to the poet Joë Bousquet which dates from Spring 1942, just a year before the death of the young philosopher who had recently joined la France Libre in London goes on to say: “Very few souls have the occasion to discover that things and beings exist. Ever since I was a child I have hoped for one thing—to receive the entire revelation before I die.” Juxtaposed with recent images of debris resulting from bombardments, in a decidedly non-chronological handmade collage, these messages resonate from someplace far away with the imperative “Ever since I was a child”, with an attention to things as they exist. Attention in the form of desire, which appears out of nowhere, between destructions occurring in two different centuries, towards an Elsewhere which is also a Here and Now—a shard of crystal, for example, whose facet is intensified when seen from this angle. This is a childhood which raises the following questions: how to make a conquest, or even a gift (a “generosity,” as Simone Weil put it), out of an attention to things as they exist, in their varying mineral or living forms? How to make not just a furtive selfie out of a fragment of crystal, but also a wider attention span; one which is long-lasting?

240 x 123 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo. © Thomas Hirschhorn/ADAGP, Paris (2022).

In the work of Rabih Mroué, messages exchanged in a digitalised and fragmented correspondence give rise to the collective strata of an alternative history of war. The Lebanese artist projects a series of visual strata—collages of newspaper clippings which leave no space for the eye to rest—onto a towering screen in smartphone format, rising up over the equivalent of two levels of the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. Rubble left behind after a bombardment, protests, explosions, deserts, more debris (Images Mon Amour, Images My Love, 2021). A monument for the crisis of memory, for a history frozen in time, this visual enumeration could go on forever (like those pre-cinematographic devices that made a series of drawings spin around a cylinder, looping the same scene over and over). Before and after, cause and effect, all of the (chrono-)logical parameters we have available in order to understand history are useless when faced with this new parade, which is also a litany: it amounts to stating what is no longer, or has not yet been, articulated. The gaze is drawn upward, sliding over this mobile ladder without ever really taking a firm hold of a world in ruins, but this large-scale scroll seems to bring a principle of repetition to life that we do not know how make analytical, historical sense of—one example is the case of Lebanon and its perpetual inter-national and inter-community conflicts, recently reactivated during the Syrian crisis.

Faced with this unpalatable layer cake of time, between the crushing gravity which brings images crashing down, and our attentions which travel upwards amongst them, constantly searching for singularity, which will win? We will need to begin by relearning how to enumerate by operating with a double-faced memory, towards the past and towards the future at the same time, resisting stupefying paralysis, even before we relearn how to analyse things in terms of chains of cause-and-effect, even before we start to ask questions about the future. Art as a modest complication of Time, a way of testing differing forms, temporally and spatially, in order to introduce understanding (and our desire to understand, or our desire, full stop) to movement.

Head image : Thomas Hirschhorn, The World (Chat-Poster), 2020. Cardboard, wood, prints, marker, adhesive, crystals

240 x 123 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo. © Thomas Hirschhorn/ADAGP, Paris (2022).

- From the issue: 101

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Some white on the map, Matter in Suspense, Describe, Lighten,

Related articles

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret

An exploration of Cnap’s recent acquisitions

by Vanessa Morisset