Printemps de l’art en Russie

Partir en Guerre

Paru récemment, Partir en Guerre d’Arthur Larrue [1] est à la fois une nouvelle mettant en scène son auteur et un essai sur les actions du groupe d’artistes de Moscou et de Saint-Pétersbourg Voïna (la guerre en russe). Le lecteur y découvre le mode de vie de ses membres, leurs convictions et la description de certaines de leurs actions, l’auteur les ayant côtoyés durant quelques mois par un hasard de la vie aussi improbable que poétique faisant se rencontrer un Français esthète hédoniste amoureux d’une Russe et une tribu de Khazars. « Quand les uns rencontrent des difficultés dans leur couple, les autres ont décidé de risquer leur vie pour bousculer la politique d’un État. » Voïna – la guerre donc – a réalisé une douzaine d’actions entre 2007 et 2011, année à l’issue de laquelle deux de ses membres furent condamnés à la prison puis s’exilèrent. L’essai d’Arthur Larrue est fidèle au mode de vie des membres de Voïna : ils vivent de peu, du vol à la tire, s’habillent de vêtements trouvés, volés, donnés, il en est de même de leur nourriture ; ce sont des ours. Mais des ours libres ! De manière significative, le regard de l’auteur est celui d’un Français qui relève du « style » dans l’accoutrement et l’attitude des membres du groupe, là où un Russe ne verrait que nécessité. Définitivement, les Voïna sont des bêtes, rustres et sauvages. Méfiants, irrévérencieux et amoraux. Le critique et commissaire russe Andrey Erofeev les compare d’ailleurs à la tradition orthodoxe des Fols-en-Christ : des illuminés va-nu-pieds errant, s’exprimant et agissant de manière incongrue et immorale, mais ayant une position marginale incontestée leur permettant d’énoncer des vérités sur tout et sur tous. Dernier point au sujet du livre : certains personnages paraissent improbables, ou trop sympathiques pour être vrais, tel le sergent Komarov du centre anti-extrémisme censé leur faire la peau. Néanmoins, le récit de cent vingt-huit pages, bien que romancé, a le mérite de décrire quelques unes de leurs actions avec vivacité et humour.

Arthur Larrue – Partir en Guerre, Paris, Allia, 2013.

Cinq ans de guerre

Quelques exemples, rétrospectivement et chronologiquement. Le 25 août 2007 à minuit, le groupe dresse un véritable banquet dans une rame de la ligne circulaire du métro moscovite en mémoire du poète russe Dmitri Prigov (1940-2007). L’action (La fête) est répétée simultanément sur trois lignes du métro de Kiev le 10 février 2008 lors de la censure de l’exposition « Common space » dans laquelle la vidéo de la performance moscovite est présentée. Manger et communier publiquement en l’honneur du poète non-conformiste est pour eux un hommage à la permissivité et à la transgression comme principes de vie.

Le 29 février 2008, deux jours avant l’élection de Dmitri Medvedev dont la victoire est prédéterminée, ils performent une orgie dans la salle du secteur « métabolisme, énergie, nutrition, digestion » du Musée national d’Histoire naturelle de Moscou. Tout cela en soutien affiché au futur président : « Baisons pour l’héritier : le petit Ours de Medvedev ! ». Le mot medved en russe signifiant « ours » et le symbole du parti Russie Unie étant un ours, l’idée d’une copulation consanguine des représentants du pouvoir et celle, ancrée, d’une Russie bestiale et primitive, l’identification au chef de meute et la reproduction de l’espèce étaient savamment et scandaleusement mélangées au travers, notamment, de slogans et de calicots.

Le 7 juillet 2008, un membre de Voïna endossant un costume improbable composé à la fois d’une soutane et d’un uniforme de la police pénètre dans une épicerie, remplit cinq sacs de produits alimentaires, d’alcool et d’un numéro du magazine Maxim puis, impunément, ressort du magasin sans payer. Les employés et les services de sécurité du magasin, fascinés sans doute par cette hydre bicéphale du pouvoir russe représentant à la fois l’Église orthodoxe et la police, ne l’arrêtent pas. Voïna commentera l’événement dans la presse : « Il n’y a pas de pouvoir du Capital en Russie. L’argent renforce le rôle de la corruption et des clans. C’est pourquoi nous refusons entièrement d’utiliser l’argent. »

Mais leur action la plus connue est bien entendu celle qui, dans la nuit du 14 au 15 juin 2010, a consisté à peindre un phallus gigantesque de soixante-cinq mètres de haut sur le pont basculant qui se dresse face au QG du FSB (ex-KGB) à Saint-Pétersbourg. Avec une peinture phosphorescente et indélébile cela va sans dire. L’année suivante, Voïna reçoit pour Dick Captured by KGB le Prix Innovatsya, l’une des deux récompenses honorifiques les plus prestigieuses du monde de l’art en Russie, décernée par une institution d’État ; principalement grâce au soutien des commissaires membres du jury, parmi lesquels se trouvaient Ekaterina Degot et Andrey Erofeev. Il s’est ensuivi un scandale phénoménal mais, bon an mal an, l’attribution du prix a été maintenue, n’épargnant pas à Oleg Vorotnikov et Leonid Nikolayev trois mois et demi de prison sous le chef d’inculpation d’« hooliganisme par haine contre un groupe social » pour avoir renversé des véhicules de police lors d’une autre action en septembre 2010. L’artiste britannique Banksy payera leur caution.

Voïna – Dick Captured by KGB, action, 14-15 juin 2010, Saint-Pétersbourg.

Entre 2007 et 2011, à travers une douzaine d’actions, Voïna aura soutenu la cause de la révolte, mais également Andrey Erofeev par un lancer de blattes de Madagascar lors de son procès en 2009, et aura largement contribué à changer l’état d’esprit apathique des Russes qui leur faisait dire à leurs débuts et à propos de l’une de leurs premières actions : « En Russie, il n’y a pas de jeunes courageux, avec un esprit sensible et révolté. Nous avons décidé de réaliser une action indisciplinée, et non l’illustration d’une idéologie. En Russie, le problème n’est pas idéologique, mais réside dans l’absence totale de vie et de volonté de faire respecter ses principes. » Depuis, la situation a changé. Les Pussy Riot leur ont emboîté le pas en chantant « Mère de Dieu, Sainte Vierge, débarrasse-nous de Poutine ! » le 21 février 2012 dans la cathédrale du Christ-Sauveur de Moscou. Deux d’entre elles sont depuis en prison, dont Nadezhda Tolokonnikova qui fut un temps membre de Voïna et qui participa à l’action du Musée national d’Histoire naturelle avant que le groupe ne se scinde en deux factions, l’une restant à Moscou et l’autre s’expatriant à Saint-Pétersbourg.

Actionnisme russe

En Russie, l’année 2012 a représenté un point culminant pour les mouvements de contestation mais aussi pour toute la société civile. Elle fut l’année des plus importantes manifestations depuis le début des années quatre-vingt-dix, l’année du retour prémédité au pouvoir de Vladimir Poutine et d’un durcissement du système, l’année des répressions sans précédent, et l’année des Pussy Riot. Une année marquante pour les artistes héritiers du mouvement que l’on nomme Actionnisme russe des années quatre-vingt-dix. Car ce mouvement, bien qu’ayant récemment reçu un surcroît de visibilité, a une histoire.

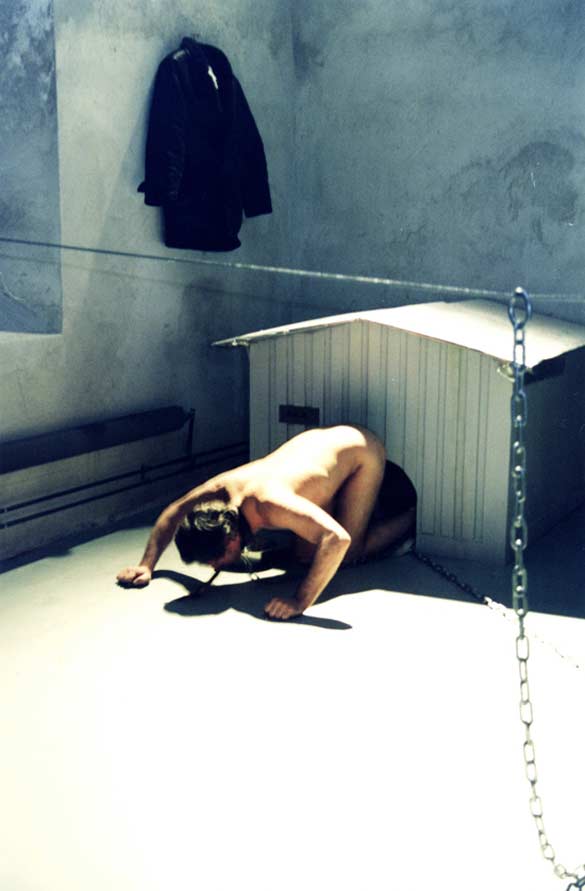

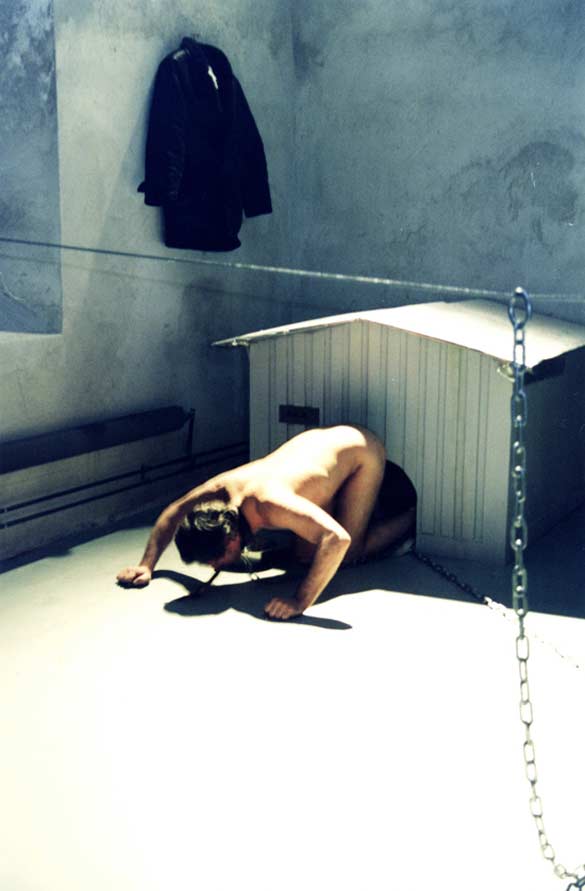

Au début des années quatre-vingt-dix, dans un contexte de totale absence d’institutions artistiques, des artistes initient des actions publiques plus ou moins violentes, dans un esprit proche de celles des Viennois des années soixante, alliant jeux théâtraux cathartiques et provocations. À titre d’exemple, le 19 mai 1994, lors du vernissage de l’exposition « L’artiste à la place de l’œuvre » à Moscou, Alexandre Brener s’impose dans l’exposition à laquelle il n’est pas invité en hurlant : « Pourquoi ils m’ont pas pris dans cette exposition ? ». Oleg Kulik, quant à lui, jouera longtemps le rôle du chien méchant. En 1996, lors de l’exposition « Interpol » du curateur Viktor Misiano présentée à Stockholm [2], Alexandre Brener détruit l’œuvre de l’artiste chinois Wenda Gu et Oleg Kulik, dans son rôle du chien, attaque et mord un visiteur, puis est arrêté par la police suédoise. Ces actions a priori contestables constituent une réponse pleine de sagacité à la déficience de communication entre les artistes — le travail de communication entre ces artistes de l’Est et de l’Ouest, qui devait donner son sens au projet, ayant échoué en amont de l’exposition du fait d’un malentendu culturel général et d’une incapacité, ou d’un refus parfois, des artistes à se comprendre. Le scandale qui en découlera, orchestré par Olivier Zahm, qui accessoirement est arrivé la veille du vernissage et ne sait rien des deux années de projet écoulées en amont, représentera le profond symptôme des différences et différends culturels, mais aussi des mécanismes et des interprétations liés à la violence [3]. Les Russes sont « des fascistes » (cf. Zahm), point. Selon Slavoj Žižek, ne pas savoir apprécier la « violence immédiate » est en soi une violence passive, par inertie, reposant sur la négation des fondements de la violence systémique et des formes de coercition subtiles inhérentes à un système. C’est rejeter le bien-fondé et la possibilité même de toute révolte. « La violence n’est pas un accident de nos systèmes, elle en est la fondation » dit-il [4]. L’actionnisme russe des années quatre-vingt-dix s’est développé dans un esprit révolutionnaire promouvant des valeurs antagonistes, démocratiques, par le bouleversement permanent, le rouleau répété d’une mer en ébullition.

Cependant, deux des principales différences entre les actions récentes et l’actionnisme de ces années sont, d’une part, leur profonde politisation et, d’autre part, leur utilisation des médias. Tant et si bien que le mouvement est parfois aujourd’hui nommé Média-activisme. Le sens même de ce qui est discuté ne réside ni dans l’objet ni même dans l’action mais dans sa médiation. Le meilleur exemple étant celui des Pussy Riot qui n’ont pas réellement chanté leur concert dans la cathédrale mais qui ont réalisé une vidéo en post-production, que nous connaissons tous. Or, c’est sur la base de cette vidéo, dont les propos ont été jugés insultants, qu’elles ont été condamnées, et non sur celle de leur performance initiale. Mais chacun fait avec ses armes.

Oleg Kulik Dog House, performance lors du vernissage de l’exposition / performance at the opening of “Interpol”, 2 février – 17 mars 1996, Färgfabriken, Stockholm. Photo : Viktor Misiano.

Rhétorique

Saisir la rhétorique du gouvernement en place est une chose fondamentale pour comprendre à la fois les non-dits et les prérequis nécessaires à l’appréciation des actions artistiques souvent jugées « trop directes » par un œil occidental ; saisir l’« absurdisme » du dialogue (simulé) entre l’État et la société civile ; saisir le double langage et la double pensée qui donnent au geste et à l’objet un caractère de second plan, ou la simple consistance d’une mue. « Mettre l’État en danger », « inciter à la haine », « insulter l’identité religieuse » sont quelques labels promptement estampillés par les autorités gouvernementales ou ecclésiastiques à chaque fois qu’une action non conforme se produit, autrement dit assez souvent. En ceci réside toute la force de la série d’Avdey Ter-Oganyan Abstractionnsime radical (2004) qui reprend et détourne des violations édictées par la Constitution pour en commenter ses dessins néo-abstraits : « Cette œuvre représente un viol de l’emblème national et du drapeau de la Fédération de Russie », « Cette œuvre représente un appel au changement par la force de la structure constitutionnelle de la Fédération de Russie », etc. Tout ceci ne doit pas se lire au premier degré, tel un manifeste ou une revendication. À l’inverse, tout réside dans le jeu latent d’une rhétorique kafkaïenne instrumentalisée par l’arbitraire. Coup d’éclat : en 2010, l’État russe, dans son aveuglement et son incapacité à sortir de cette logique autoritaire, tombe dans le panneau et interdit l’exposition des œuvres au Louvre [5]. Cette réaction de l’État comme réponse à une invitation au dialogue de sourds absurde est précisément ce qui constitue l’œuvre. Avdey Ter-Oganyan en conviendra, sans cela il n’y aurait eu que du papier plus ou moins coloré et un travail d’autiste. L’artiste ne fait qu’initier le projet et, malgré lui, l’État est souvent le co-auteur de l’œuvre.

Ainsi, face au pouvoir, les artistes emploient une violence nécessaire et équivoque, n’ayant rien d’évident ni de direct. Les artistes russes dans la mouvance de l’actionnisme se sont affranchis de l’objet de manière beaucoup plus souterraine que – par comparaison – les interventionnistes des années deux mille en Europe et aux États-Unis. Vingt ans de capitalisme en Russie n’ont pas effacé la culture et le regard non spéculatifs que les artistes ont porté au XXe siècle et portent encore sur l’objet. Il en est de même du geste et de l’action ; de même de ce que nous appelons « la violence ». Une violence que nous n’aimons pas voir, que nous préférerions oublier. Mais, en fin de compte, la violence suprême ne réside-t-elle pas dans le déni, le silence et l’oubli ?

- ↑ Arthur Larrue, Partir en Guerre, Paris, Allia, 2013.

- ↑ Du 2 février au 17 mars 1996, Färgfabriken, Stockholm, Suède.

- ↑ Voir le site de Moscow Art Magazine : xz.gif.ru ainsi que : Interpol: The Art Exhibition Which Divided East and West, Eda Čufer et Viktor Misiano (Ed.), Ljubljana, IRWIN et Moscow Art Magazine, 2001.

- ↑ Slavoj Žižek, Violence. Six réflexions transversales, Vauvert, Au Diable Vauvert, 2012.

- ↑ Contrepoint, l’art contemporain russe – De l’icône à l’avant-garde en passant par le musée, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 14 Octobre 2010-31 Janvier 2011.

Art Spring in Russia

Off to War

Arthur Larrue’s recently published book Partir en Guerre [1] is at once a short story written in the first person and an essay about the actions of the Moscow- and St.Petersburg-based group of artists, Voïna (which means “war” in Russian). In this book, readers discover how the group’s members live, along with their convictions and a description of some of their actions—the author rubbed shoulders with them for several months through one of those coincidences which is as unlikely as it is poetic, whereby a French aesthete and hedonist in love with a Russian woman met a tribe of Khazars. “When some people have problems with their couple, others have decided to risk their lives to jostle the politics of a State.” Voïna—so, war—carried out a dozen actions between 2007 and 2011, at the end of which year two of its members were sentenced to prison terms, and then went into exile. Arthur Larrue’s essay is accurate about the life style of Voïna members: they live on next to nothing, pickpocketing, wearing clothes they have found, stolen, or been given, and the same applies to how they feed themselves—they are bears. But free bears! In a significant manner, the author’s eye is that of a Frenchman who finds “style” in the trappings and attitude of the group’s members, precisely where a Russian would see just necessity. No doubt about it, the Voïna people are beasts, rugged and wild. Suspicious, irreverent and amoral. The Russian critic and curator Andrey Erofeev incidentally compares them to the orthodox tradition of the Fools-for-Christ, roaming barefoot visionaries, expressing themselves and acting in an incongruous and immoral way, but enjoying an undisputed fringe position enabling them to utter truths about everything, and everyone. The book’s final point is that some characters seem improbable, or too sympathetic to be true, one such being sergeant Komarov of the anti-extremism centre, supposed to destroy them. Nevertheless, and though novelistic, the 128-page narrative has the merit of describing some of their actions in a lively and witty way.

Five years of war

One or two examples, with hindsight, and chronologically. On 25 August 2007, at midnight, the group set up a banquet, no less, in a Moscow metro train in memory of the Russian poet Dmitri Prigov (1940-2007). The action (The Party) was repeated simultaneously on three metro lines in Kiev on 10 February 2008, during the censorship of the exhibition “Common Space” in which the video of the Moscow performance was screened. For them, eating and communing in public in honour of a non-conformist poet is a tribute to permissiveness and transgression as life principles.

On 29 February 2008, two days before the election of Dmitri Medvedev, whose victory was pre-ordained, they performed an orgy in the “metabolism, energy, nutrition, digestion” room at the Museum of Natural History in Moscow. All that in blatant support of the future president: “Fuck for the Heir: Medvedev’s little Bear!” The word medved in Russian meaning “bear” and the symbol of the United Russia party being a bear, the idea involved a consanguine copulation between the representatives of power, and the established copulation of a bestial and primitive Russia; the identification with the head of the pack and the reproduction of the species were shrewdly and scandalously mixed together, in particular through slogans and banners.

On 7 July 2008, a Voïna member wearing an unlikely costume consisting of both a priest’s cassock and a police uniform walked into a grocery, filled five bags with food, alcohol and an issue of the magazine Maxim, and then, with impunity, walked out of the shop without paying. Probably fascinated by this two-headed hydra of Russian power, representing both the orthodox Church and the police, the shop’s employees and security service did not arrest the thief. Voïna had this to say about the event in the press: “ There is no power of Capital in Russia. Money reinforces the role of corruption and clans. This is why we totally refuse to use money.”

But their best known action, needless to say, is the one which, during the night of 14-15 July 2010, consisted in painting a gigantic phallus, 215 feet high on the bascule bridge opposite the headquarters of the FSB (which used to be the KGB) in St. Petersburg. It goes without saying that the paint was phosphorescent and indelible. In the following year, for Dick Captured by KGB, Voïna was awarded the Innovatsya prize, one of the two most prestigious honorary prizes handed out by the art world in Russia, awarded by a State institution—mainly thanks to the support of curators on the jury, including Ekaterina Degot and Andrey Erofeev. A phenomenal scandal duly erupted but through it all the award held good, although Oleg Vorotnikov and Leonid Nikolayev were given three-and-a-half-month prison sentences after being indicted for “hooliganism through hatred for a social group”, for having upturned some police vehicles during another action in September 2010. The British artist Banksy paid their bail.

Pussy Riot Sainte Marie, Mère de Dieu, débarrasse-nous de Poutine ! / Mother of God, Holy Virgin, drive away Putin!, 21 février 2012, cathédrale du Christ-Sauveur, Moscou / cathedral of Christ the Savior, Moscow. http://freepussyriot.org

Between 2007 and 2011, through a dozen actions, Voïna put its weight behind the cause of revolt, as well as supporting Andrey Erofeev, by throwing Madagascan cockroaches during his 2009 trial, and considerably contributed to altering the apathetic state of mind of Russians which caused them to remark, in their early days, and with regard to one of their first actions: “In Russia, there are no brave young people, with sensitive minds and up in arms. We have decided to carry out an unruly action, and not the illustration of an ideology. In Russia, the problem is not ideological, but lies in the total absence of life and any desire to have one’s principles respected.” The situation has since changed. Pussy Riot followed in their footsteps singing: “ Mother of God, Holy Virgin, drive away Putin!” on 21 February 2012 in the cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow. Two members of the group have since been in prison, including Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, who was once a Voïna member and took part in the action at the National Museum of Natural History before the group split into two factions, one remaining in Moscow, the other moving away to St. Petersburg.

Russian Actionism

In Russia, the year 2012 represented a high point for protest movements, as well as for the whole of civil society. It was the year which saw the largest demonstrations since the early 1990s, the year of Vladimir Putin’s premeditated return to power, and the year which saw the system toughening its stance, the year of unprecedented acts of repression, and the year of Pussy Riot. So it was a decisive year for artists who are heirs of the 1990s’ movement that was called Russian Actionism. For although this movement has recently received excessive visibility, it does have a history.

In the early 1990s, in a context of total absence of art institutions, artists started to stage more or less violent public actions, in a spirit akin to the actions of Viennese artists in the 1960s, combining cathartic theatrical games and provocations. By way of example, on 19 May 1994, during the opening of the exhibition “The Artist instead of the Work in Moscow”, Alexander Brener took the floor in the show to which he had not been invited, shouting: “Why didn’t they include me in this exhibition?” Oleg Kulik, for his part, would for a long time play the role of the dangerous, biting dog. In 1996, during the exhibition “Interpol”, organized by the curator Viktor Misiano and held in Stockholm, [2], Alexander Brener destroyed the work of the Chinese artist Wenda Gu, and Oleg Kulik, in his canine role, attacked and bit a visitor, and was then arrested by the Swedish police. These at first sight disputable actions offer an extremely sagacious response to the lack of communication between artists— the work of communication between these artists from the East and the West, which were meant to give the project its meaning, having foundered ahead of the exhibition because of a general cultural lack of understanding and an inability, or at times a refusal, on the part of the artists to understand one another. The scandal which would then ensue, orchestrated by Olivier Zahm, who arrived, as it happened, on the eve of the opening and knew nothing about the two years already spent on the project, represented the deep-seated symptom of the various differences and cultural disagreements, but also of the mechanisms and interpretations associated with violence. [3]. The Russians were “fascists” (cf. Zahm), period. According to Slavoj Žižek, not knowing how to appreciate “immediate violence” is in itself a passive form of violence, through inertia, based on the negation of the foundations of systemic violence and forms of subtle coercion inherent in the system. It is to reject the validity and the very possibility of any revolt. “Violence is not an accident of our systems, it is their foundation”, he says. [4]. The Russian Actionism of the 1990s developed in a revolutionary spirit promoting antagonistic, democratic values, through permanent upheaval, the repeated wave in a stormy sea.

However, two of the main differences between the recent actions and the Actionism of those bygone years are, on the one hand, their deep politicization and, on the other, their use of the media. To such a degree that the movement is sometimes nowadays called Media-activism. The actual meaning of what is discussed resides neither in the object nor even in the action, but in its mediation—its media coverage. The best example being that of Pussy Riot, who did not really sing their concert in the cathedral, but who made a post-production video, which we are all acquainted with. It is actually on the basis of this video, whose ideas were deemed insulting, that the young women were found guilty and sentenced, and not on the basis of their initial performance. But everyone makes do with what they have, whatever their weapons.

Rhetoric

Grasping the rhetoric of the government in power is fundamental for understanding both what is left unsaid and the prerequisites necessary for the appreciation of artistic actions often deemed to be “too direct” by a western eye; grasping the “absurdism” of the “simulated” dialogue between the State and civil society; grasping the double language and the double thinking which lend the gesture and the object a background character, or the simple consistency of a slough. “Endangering the State”, “inciting hatred”, “insulting religious identity”, these are some of the labels promptly trotted out by government and ecclesiastical authorities whenever a non-conformist action occurs, otherwise put, quite often. Herein resides all the strength of Avdey Ter-Oganyan’s series Abstractionnsime radical (2004) which takes up and hijacks violations decreed by the Constitution to provide commentary for his neo-abstract drawings: “ This work represents a rape of the national emblem and flag of the Russian Federation”, “This work represents a call for change through force of the constitutional structure of the Russian Federation”, etc. None of this should be taken literally, like a manifesto or a challenge. Conversely, everything resides in the latent interplay of a Kafkaesque rhetoric exploited by the arbitrary. A great feat: in 2010, in its blindness and its inability to get away from this authoritarian logic, the Russian State fell into the trap and banned the exhibition of these works in the Louvre [5]. This State reaction as a response to an invitation to an absurd dialogue of the deaf is precisely what constitutes the work. Avdey Ter-Oganyan would agree, for without that there would simply have been more or less colourful paper and the work of an autistic person. The artist is only initiating the project, and, despite itself, the State is often the co-author of the work.

So in the face of power, artists employ a necessary and ambiguous violence, which has nothing evident or direct about it. The Russian artists in the Actionist movement have freed themselves from the object in a much more underground way—by comparison—than the Interventionists of the 2000s in Europe and the United States. Twenty years of capitalism in Russia have not done away with culture, or the non-speculative eye cast by artists on the 20th century, and still cast by them on the object. The same goes for gesture and action; just as it does for what we call “violence”. A violence which we do not like seeing, which we would prefer to forget about. But, in the end of the day, does the supreme violence not reside in denial, silence, and oblivion?

- ↑ Arthur Larrue, Partir en Guerre, Paris, Allia, 2013.

- ↑ From 2 February to 17 March 1996, Färgfabriken, Stockholm, Sweden.

- ↑ See the website of Moscow Art Magazine : xz.gif.ru as well as : Interpol: The Art Exhibition Which Divided East and West, Eda Čufer and Viktor Misiano (Ed.), Ljubljana, IRWIN and Moscow Art Magazine, 2001.

- ↑ Slavoj Žižek, Violence. Six Sideways Reflections, London, Profile Books Ltd, 2008.

- ↑ Contrepoint, l’art contemporain russe – De l’icône à l’avant-garde en passant par le musée, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 14 October 2010-31 January 2011.

articles liés

Le marathon du commissaire : Frac Sud, Mucem, Mac Marseille

par Patrice Joly

Pratiquer l’exposition (un essai scénographié)

par Agnès Violeau

La vague techno-vernaculaire (pt.2)

par Félicien Grand d'Esnon et Alexis Loisel Montambaux