Derniers usages de la littérature

La rencontre entre l’art et la littérature est un serpent de mer qui ne cesse de resurgir avant de replonger dans les replis de l’indifférence jusqu’à ce qu’un écrivain fictionnalise un artiste dans un de ses romans ou qu’un artiste reprenne un bouquin sur une étagère et décide de le réécrire ou de l’incorporer à son travail. Bien sûr, la matière littéraire et l’objet livre ne sont pas tout à fait du même tonneau qu’une planche de contreplaqué ou qu’un morceau de placoplâtre : le livre résiste à l’assimilation, quant au texte, il est volatil. Si « l’exploitation » de l’objet livre dans des installations ou des oeuvres complexes n’est pas nouvelle, elle s’est vue récemment revisitée par des propositions radicales de jeunes artistes qui s’essaient à prolonger ou à « augmenter » le sens de l’oeuvre, sans pour autant vouloir rouvrir le débat du modernisme et encore moins celui de la transdisciplinarité. Ces initiatives se démarquent toutefois de celles de curateurs qui, eux, se placent dans l’orbite d’oeuvres littéraires majeures, allant jusqu’à en emprunter les titres pour les donner à leurs expositions. Il s’agit alors autant de se plonger dans l’univers des écrivains que de tenter de reconstituer des ambiances où les disciplines dialoguent et se répondent ou de transcrire des préoccupations esthétiques d’une discipline vers l’autre ; à ce propos, la difficulté d’une véritable correspondance entre littérature et arts visuels reste entière : peut-on traduire des émotions littéraires, des visions intérieures comme l’univers de la littérature en est seul a priori capable, dans celui des arts plastiques ?

Matérialité insaisissable

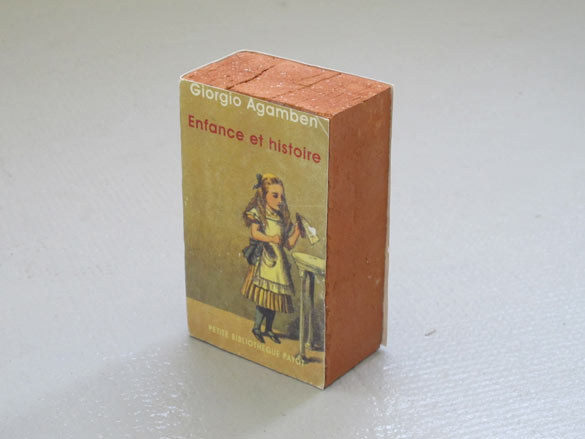

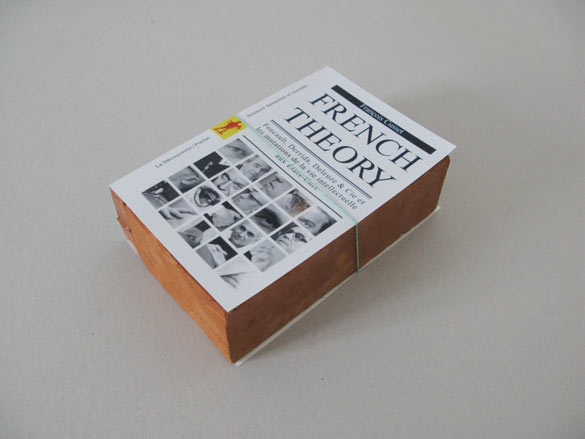

Les Brickbats de Claire Fontaine sont de véritables briques recouvertes de couvertures de livres célèbres – que le langage populaire désigne familièrement par le nom de pavé – dont les « rééditions » se succèdent allègrement depuis leur première apparition au début des années deux mille, parsemant foires et expositions de leur présence choc. Si cette pièce est un best seller c’est qu’elle combine la matière artistique et la matière littéraire en se jouant du signifiant pavé via une formule particulièrement efficace. Son succès tient également au fait qu’elle prolonge la vie de ces livres qui, tous, d’une manière ou d’une autre, ont marqué leur époque : le choix des ouvrages n’est pas anodin, Enfance et histoire, French Theory, etc. et leur transformation en leur pendant sculptural intervient dans le prolongement d’une réflexion où les mots ont du poids. Le travail de Claire Fontaine sur ces derniers ne nie pas l’énoncé, il le surligne en lui donnant une plasticité explosive, brûlante, faisant ainsi advenir une performativité enfouie : ainsi de ce « Strike » en lettres de néon qui s’illumine brusquement à l’approche des spectateurs. Il en va tout autrement des « pavés » dont la force performative demeure légèrement en sommeil, prête cependant à se réaliser à tout moment. La dimension sociale est également très présente dans ce travail qui pointe « l’illisibilité » de ces ouvrages et la distance qu’ils instaurent envers un lecteur non lettré : les artistes cherchent ainsi à réduire cet écart en en permettant une réappropriation par tout un chacun, d’autant plus forte que la symbolique du pavé comme arme de la rébellion populaire est ici réaffirmée. Quand bien même il ne s’agit pas de fusion totale entre littérature et arts plastiques, les divers détournements de sens et d’usage que le duo imprime à ces volumes permettent de « corriger » la littérature en lui donnant littéralement plus de poids mais, d’une certaine manière, plus de légèreté.

Chez Thu Van Tran, il entre un peu de ce désir de « rectification » dont il est question dans les Brickbats de Claire Fontaine ; l’objet livre est très présent dans le travail de la jeune artiste franco-vietnamienne et particulièrement l’ouvrage de Conrad, Au coeur des ténèbres, doublement repris et prolongé. Pour Sans tache, elle a plongé le livre dans une encre noire qui dégorge sur le plâtre d’un socle immaculé. L’intention apparaît d’emblée : il s’agit de rendre immédiatement « lisible » la densité et le côté sombre du récit. Le choix de ce dernier permet également de faire émerger les connotations post-coloniales d’un auteur qui n’est pas censé faire partie des références habituelles, Conrad n’étant pas spécialement associé à une posture émancipatrice. Un traitement similaire avait déjà été envisagé pour le livre de Duras, Écrire, du moins en ce qui concerne l’acte de plonger l’objet dans un liquide colorant : avec Écrire Duras, Thu Van Tran réintègre dans son travail de plasticienne une technique qui consiste à verser du bleu de méthylène sur les livres pour les rendre illisibles. Le matériau de destruction massive se transforme alors en pigment, composante indispensable de la pratique du peintre ; le livre devient réceptacle, les pages monochromes. Mais plus que dans Sans tache où, somme toute, il est avant tout question de détourner l’usage d’un objet, c’est la pièce Au plus profond du noir qui s’avère être la plus fusionnelle avec l’oeuvre d’un grand écrivain, puisque l’artiste s’en prend ici au corpus littéraire lui-même et à ses voies de diffusion à partir de son socle langagier, à savoir la traduction : Thu Van Tran a écrit sa propre version du récit conradien, dans une langue simple, avec ses mots à elle. Le désir d’appropriation se double ici d’une volonté de franchir les barrières de l’érudition et de la distinction habituellement associées au chef-d’oeuvre.

Claire Fontaine. Enfance et histoire brickbat, 2007. Brique, fragments de briques, impression numérique sur papier haute qualité, élastique (optionnel) / Brick, brick fragments and digital archival print with optional elastic band. 170 × 110 × 58 mm. Courtesy Claire Fontaine ; Galerie Air de Paris, Paris ; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo : Claire Fontaine.

Daniel Gustav Cramer. Untitled (Moby Dick), 2013. Livre / Book. Courtesy BolteLang, Zürich ; Sies & Höke, Düsseldorf ; Vera Cortes, Lisboa ; Daniel Gustav Cramer. Photo : La Kunsthalle, Mulhouse.

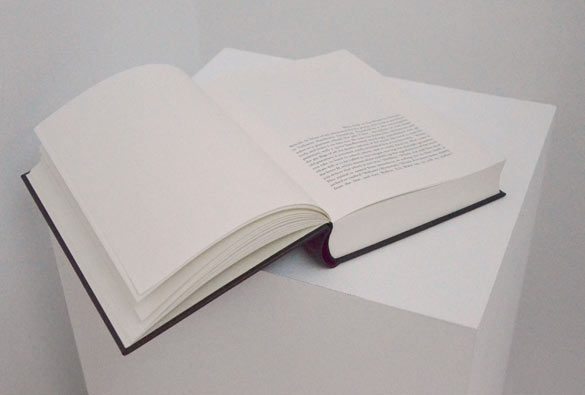

Untitled (Moby Dick) de Daniel Gustav Cramer n’est pas très éloigné de cette démarche même s’il n’y est ni question de briser la logique du récit ni de remettre en cause l’autorité de la traduction : le texte est ici frappé au kilomètre en faisant disparaître pagination, paragraphes et autres ordonnancements graphiques. Le récit est perturbé dans son mode d’apparition : en s’affranchissant du rythme des paragraphes et des césures, en supprimant tout effet, l’artiste allemand met en lumière l’interdépendance du graphisme et de la lisibilité, de l’esthétique et de l’autorité du « grand récit » qui s’en trouve soudain altéré. Il résulte de cette violence un monstre qui rend toute lecture impossible, privé de ses apprêts et du confort que lui procure le « traitement de texte » : le passage à la plasticité cette fois-ci se fait au détriment de l’acte de lecture, le sculptural ayant définitivement achevé le littéraire.

Dans les exemples ci-dessus, on assiste à un regain d’intérêt pour le livre – texte autant qu’objet – que les artistes envisagent comme une matière première pas tout à fait comme les autres. Dans l’hommage ambivalent adressé à cet objet dont la matérialité ne peut s’appréhender qu’à la lumière de l’immatérialité dont il est le support, se mêlent le désir de transgresser l’autorité de l’oeuvre littéraire et la tentation d’utiliser la forme livre débarrassée de son contenu, le récit « premier », afin de le faire rentrer dans le champ de leur propre sensibilité… Pour ce qui est de la relation des curateurs et des grandes oeuvres de la littérature, il n’en va pas forcément de même, le respect semble cette fois-ci de mise, l’idée étant plus de chercher des correspondances et des passages entre deux disciplines a priori irréductibles l’une à l’autre.

Joyce, Roussel, Sebald…

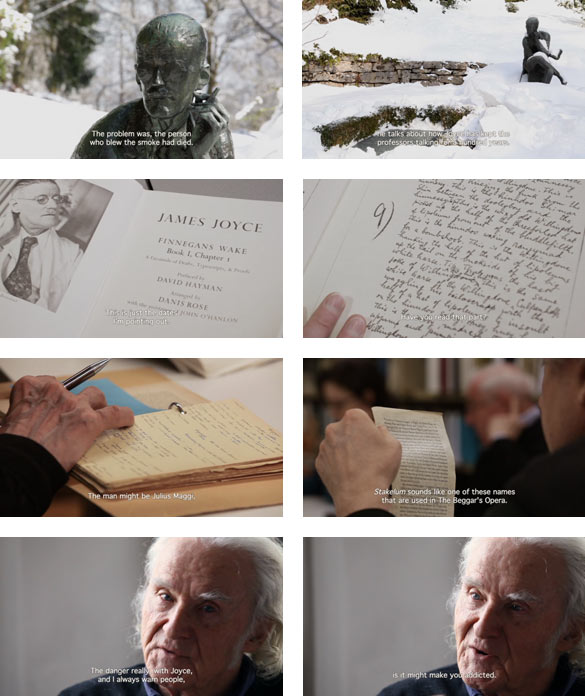

Joycean Society est un documentaire sur la société éponyme fondée il y a une trentaine d’années dans le but de déchiffrer le texte censément le plus énigmatique de James Joyce, Finnegans Wake. La caméra de Dora Garcia s’est introduite dans l’une des réunions qu’elle enregistre en temps réel. Le film commence par un aparté autour de l’artiste Damien Hirst que les membres ne semblent pas spécialement apprécier, et que la baisse de sa cote, financière s’entend, ne paraît ni réjouir ni affecter outre mesure, puisqu’ils ont l’air de considérer qu’il n’est pas en phase avec la société actuelle et que son art est déconnecté de la réalité. Plus la séance avance et plus l’incipit a priori hors sujet semble se justifier, au fur et à mesure que l’interprétation érudite mais joyeuse, pleine d’humour et tâtonnante des sociétaires, nous ouvre les arcanes d’un texte réputé insaisissable pour les béotiens. Le décryptage savant fait grandement appel à l’intuition des participants – charmant aréopage de vieillards affutés doté de quelques jeunes gens aussi muets que remplis d’admiration pour leurs aînés – mais laisse cependant beaucoup d’énigmes inexpliquées. L’oeuvre apparaît totalement en dialogue avec son temps, puisant aussi bien dans les registres portuaires de la ville de Dublin que dans l’Encyclopædia Britannica – le wikipédia de l’époque – dans laquelle le grand écrivain pioche sans vergogne pour alimenter son épopée, copie-colle des listes impressionnantes de substantifs et de noms propres qu’il reconstruit à l’envi, en jouant à n’en plus finir avec le langage.

Ce documentaire peut apparaître à certains égards comme un conte un brin manichéen opposant des artistes obnubilés par le succès à des hommes de bonne volonté, tel l’écrivain irlandais dont l’oeuvre continue d’inspirer des lectures et de fédérer des enthousiasmes soixante-dix ans après sa mort. La société littéraire qu’il dépeint n’apparaît pas très éloignée d’une société idéale où la parole des (vieux) sages est enfin reconnue et entendue, où le mélange des générations se fait par le biais de purs échanges intellectuels et dans un souci commun de la littérature : une espèce de public rêvé qui semble laisser rêveuse la réalisatrice. On pourrait presque y discerner une indicible jalousie pour une attention portée à l’endroit de la littérature, comme si cette dernière, à la différence des arts plastiques, continuait à susciter une incomparable empathie.

Est-ce pour cette raison que l’on assiste à une floraison d’expositions qui convoquent des auteurs majeurs de la littérature, de Sebald à Joyce [1] en passant par Roussel ? Pourquoi donc se réclamer de ces oeuvres emblématiques ? Est-ce la nostalgie d’une époque encore pleine des illusions du modernisme qui les rend si désirables ? Est-ce le rejet d’un matérialisme omniprésent qui colonise les foires et les galeries d’art, creusant chaque jour un peu plus le fossé entre la valeur spirituelle de l’oeuvre d’art et sa marchandisation à outrance qui anime ces démarches ? Il ne semble cependant pas qu’un unique dessein moral se cache derrière le recours à ces oeuvres mais une multiplicité de raisons qui sont autant de l’ordre de la captation d’une époque – pour laquelle la littérature semble plus adaptée – que de l’analyse du potentiel fertilisateur de ces gens d’exception que sont les grands auteurs.

Thu Van Tran. Au plus profond du noir, 2013. Traduction du récit de Joseph Conrad « Heart of Darkness », livres sur palette en bois d’hévéa / Translation of Joseph Conrad’s novel “Heart of Darkness”, books on hevea pallet. Courtesy Galerie Meessen De Clercq, Bruxelles. Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view « La 18e place », Villa du Parc. Photo : Isa Meunier-Fleury.

Mike Kelley. Kandor 10B (Exploded Fortress of Solitude), 2011. Courtesy Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. © Estate of Mike Kelley. Tous droits réservés / All rights reserved. Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view « Nouvelles Impressions de Raymond Roussel ». Photo : André Morin.

François Piron, dans son texte d’introduction à l’appareil critique qui accompagne l’exposition « Nouvelles impressions de Raymond Roussel », se défend d’avoir voulu faire une « exposition d’écrivain » [2]. À la lecture des différentes contributions qui composent cet ensemble, on comprend un peu mieux ce qui a présidé à la conception d’une exposition autour de la figure de Roussel. Loin d’être seulement écrivain, ce dernier est avant tout un inventeur qui s’est essayé à de nombreuses expérimentations, en commençant par le théâtre auquel il a voué dès son enfance une vénération qui ne s’est jamais démentie. L’identité roussellienne s’est apparemment constituée sur le mode d’une admiration sans bornes pour l’oeuvre de Pierre Loti qu’il plaçait au sommet de l’Olympe littéraire ; fait étrange pour un écrivain qui est resté célèbre dans le monde des lettres pour avoir créé une écriture pour le moins désincarnée, « plate », et dédiée à la description minutieuse des choses plutôt qu’à celle des hommes. Roussel a profondément influencé l’oeuvre de Duchamp et rien que pour cela il mériterait d’être célébré comme un pionnier de l’art contemporain. Pourquoi vouloir aujourd’hui réinvestir la figure d’un écrivain disparu à la fin des années trente, au-delà d’une réévaluation largement justifiée de son importance réelle ? Son ascendance sur la scène française du début du xxe siècle étant déjà grandement reconnue, l’un des mérites des « Nouvelles impressions… » est justement de montrer l’influence de l’auteur de Locus Solus hors des frontières nationales et dans sa très grande contemporanéité. Dès le début, la précision portée à son paroxysme de l’écriture roussellienne intéresse fortement ses contemporains. Duchamp en premier, pour lequel ce qui prime chez Roussel, c’est la capacité de son écriture à intervenir sur le terrain même de l’image : il est conquis en « voyant » les Impressions d’Afrique au théâtre – et non pas en lisant ses livres, comme le rappelle Bernard Marcadé [3] – elles l’influenceront plus tard dans la réalisation du Grand Verre qu’il qualifie lui-même de peinture de « précision et de minutie ». À quelques décennies d’intervalle, ce sera cette fois-ci « une mystérieuse utilisation du temps que Mark Manders a su le mieux extrapoler de l’univers de Roussel [4] », référant de la sorte les anachronies et les asynchronismes de son travail à l’oeuvre roussellienne. Avant cela, le français expatrié à Los Angeles Guy de Cointet avait été impressionné par « la technique roussellienne de fabrication à partir de mots trouvés et par homophonie » [5] dont s’inspirent en droite ligne ses premières interventions scéniques. Un autre angelino, natif des USA celui-là, Mike Kelley, avoue avoir été attiré par l’écrivain et ses jeux sur le langage ; ses premières performances rappellent de Cointet dans sa manière d’assembler des objets-phonèmes pour construire des phrases grammaticalement correctes mais dénuées de sens. On y retrouve encore cette minutie du langage de Roussel qui, à force de description microscopique, quasi scientifique, finit par perdre de vue son objet pour devenir… poésie. On le voit, les suites rousselliennes sont multiples et concernent des dimensions de la création ayant peu de rapport entre elles, allant des décalages temporels à la structure du langage qui intéressera en son temps l’OuLiPo. À tel point qu’il est difficile de déceler une quelconque unité à l’intérieur de ce paradigme d’inspiration. Toujours est-il que ces « bombes à retardement » dont parle Bernard Marcadé [6] produiront leurs effets bien après la disparition de Roussel et l’on attend encore leurs dernières déflagrations.

Winfried Georg Sebald est mort au tout début de la décennie deux mille et son oeuvre n’a depuis cessé de résonner dans le champ de l’art contemporain : Nicolas Bourriaud, en plein travail de préparation de ses expositions « Strates » à Murcie et « La consistance du visible » à la Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, insiste sur la place que l’écrivain allemand occupe au sein de ses préoccupations. Sebald illustre parfaitement les thèses de l’ancien directeur du Palais de Tokyo qui partent du principe que l’Histoire, ses faits, ses événements, ses bifurcations, composent un grand livre ouvert et que la faculté d’y errer à loisir peut tenir lieu de principe fédérateur pour toute une génération d’artistes [7]. Cette « spatialisation » de l’Histoire, ainsi qu’il le formule, se retrouve effectivement au coeur de l’équation sebaldienne : ce dernier se livre dans l’ensemble de ses ouvrages à une déambulation tous azimuts qui entremêle l’Histoire à ses propres histoires, les faits de première importance à ses anecdotes de voyage, n’hésitant pas à superposer les diverses strates du récit, revenant sur les traces de ses prédécesseurs, puisant dans sa propre mémoire au même titre que dans la mémoire collective. L’exposition présentée au Mudam jusqu’à la fin de l’été et qui reprend le titre de l’ouvrage de Muriel Pic, L’image-papillon, fait référence à la technique que Sebald a utilisée dans ses derniers ouvrages [8] consistant à insérer des images dans le flot du texte. Ce procédé est foncièrement dialectique, comme l’analyse Muriel Pic, puisque d’un côté, il fige la mémoire, empruntant à la méthode scientifique sa dimension de collecte et d’archivage, et de l’autre, il rejoint la propension de l’esprit à virevolter de manière imprévisible et empathique d’un souvenir à l’autre. Le propos de l’exposition de Christophe Gallois est là encore de s’inspirer d’une oeuvre littéraire empreinte d’une grande complexité. L’exercice est plutôt concluant dans la mesure où ce dernier réunit des artistes qui se rapprochent fortement des préoccupations de l’écrivain. Cependant, il semble que le caractère révolutionnaire de l’écriture de Sebald ne soit pas complètement rendu car ce dernier va bien plus loin qu’enchevêtrer les récits et mixer les différents registres mémoriels, il se livre à une véritable rupture ontologique, son écriture n’est pas seulement écriture, elle brise le tabou de la coprésence du texte et de l’image et pointe « l’incomplétude du texte. » Se faisant, Sebald déborde le champ de l’écriture pour se poster à la frontière du cinéma, à travers le montage, comme le fait remarquer encore Muriel Pic [9]. De fait, comme en son temps Roussel avait influencé Duchamp, Sebald possède ce magnétisme de l’écrivain qui ose dépasser les limites de l’écriture pour aller ensemencer le champ de l’art en venant à nouveau sur le terrain de l’image. Mais l’oeuvre de Sebald est aussi traversée par la vision d’une humanité profondément auto-destructrice, sa littérature tout entière est orientée vers cette quête unique qui lui fait rechercher à travers tout type de document les preuves de cette intuition [10]. L’édifice sebaldien repose intégralement sur la poursuite de cette obsession morale qui le pousse à repousser les limites du « roman. » La pente mélancolique de son oeuvre n’est peut-être pas pour rien dans la séduction qu’il exerce auprès des artistes et des curateurs mais aussi d’une population fidèle de lecteurs.

- ↑ Voir notamment l’exposition « Slow Season » du collectif Mahony au centre d’art la Criée de Rennes et sa chronique dans ce même numéro de 02, en réponse directe à la thématique générale du Frac Bretagne ayant choisi comme emblème la figure d’Ulysse pour célébrer les trente ans de l’institution. De nombreuses propositions se sont emparées de la figure de l’Ulysse de Joyce, l’entremêlant à celle du héros de Homère(FRAC Bretagne).

- ↑ Palais n˚17, printemps 2013, p. 77, article introductif de François Piron.

- ↑ « La vision – il faudrait dire la vue – des Impressions d’Afrique convainc définitivement Duchamp de s’éloigner des références picturales avec lesquelles il était jusqu’ici empêtré (Cézanne, le cubisme, Matisse…) », Palais, op.cit., p. 98, article de Bernard Marcadé, « Duchamp / Roussel : quelques points de coïncidences et de tangences. »

- ↑ Ibid., page 125, « Mark Manders : une expérience pour multiplier le présent », article de Lorenzo Benedetti.

- ↑ Ibid., page 110, article de Marie de Brugerolle, « Roussel in California : Cointet, Leavitt, Fisher, Kelley… ».

- ↑ Ibid., page 105, article de Bernard Marcadé, « Duchamp / Roussel : quelques points de coïncidences et de tangences. »

- ↑ Cf. entretien avec Aude Launay, 02 n˚47 : interview avec nicolas bourriaud

- ↑ Il s’agit de Vertiges, Les Émigrants, Les Anneaux de Saturne et Austerlitz.

- ↑ « L’invention littéraire de Sebald relève du montage, méthode littéraire que Benjamin développa au niveau cognitif et dont le matérialisme cède la priorité aux traces. » « Grâce au montage, Sebald livre une vision du passé qui s’émancipe de la logique chronologique puisque les récits se construisent par collisions et associations, anachronies. » in Muriel Pic, L’image papillon, Presses du réel, 2009, p. 13.

- ↑ « Rendre compte des réalités, de la destruction, faire prendre conscience de la logique du désastre qui gouverne l’histoire de l’humanité est la seule raison valable de faire oeuvre littéraire. » Muriel Pic, op.cit., p. 11.

- Claire Fontaine, « Exposition / Exhibition Prix Marcel Duchamp 2013 », Musée des Beaux-arts de Libourne ; 25.05 – 15.09.2013.

- Thu Van Tran, « La 18e place », Villa du Parc, Annemasse ; 17.05 – 13.07.2013.

- Daniel Gustav Cramer, « Ten works », La Kunsthalle, Mulhouse ; 31.05 – 25.08.2013.

- Dora Garcia, The Joycean Society (commissariat / curated by : Abdellah Karroum / Fondation Prince Pierre de Monaco), Biennale de Venise, Punch Space, Giudecca, Venise, 30.05 – 24.11.2013 ; Sélection officielle / Official Selection FID Marseille, 2 – 8.07.2013 ; Transcinema, Lima, 4 – 14.07.2013 ; ProjecteSD, Barcelone, 13.09.2013 ; Centro José Guerrero, Grenade (commissariat / curated by : Yolanda Romero), 27.09 – 8.12.13 ; DMZ Korean International Documentary Film Festival, Gyeonggi-do, 17 – 23.10.2013 ; Kunsthaus Bregenz (commissariat / curated by : Eva Birkenstock), 19.10.2013 – 12.01.2014.

- « Nouvelles Impressions de Raymond Roussel », Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 27.02 – 20.05.2013, commissariat / curated by : François Piron.

- « L’Image papillon », Mudam, Luxembourg, 23.03 – 08.09.2013, commissariat / curated by : Christophe Gallois.

The Last Uses of Literature

The encounter between art and literature is an old chestnut, forever showing up again, before plunging back into the recesses of indifference, until a writer fictionalizes an artist in one his novels, or an artist takes a book down from a shelf and decides to re-write it, or incorporate it in his work. Needless to say, literary material and the book as object are not altogether of the same ilk as a sheet of plywood and a piece of sheetrock: the book resists assimilation, while the text is volatile. If the “exploitation” of the book as object in installations and complex works is nothing new, it has recently been re-visited by radical proposals made by young artists trying to prolong or “augment” the meaning of the text, though without wishing to re-open the debate on modernism, and even less the subject of cross-disciplinarity. These initiatives are nevertheless distinct from those of curators who, for their part, put themselves in the orbit of major literary works, even going so far as to borrow their titles for their own shows. What is thus involved is both delving into the world of writers and trying to re-create atmospheres where disciplines dialogue and answer each other, or transcribe the aesthetic concerns of one discipline to another. In this respect, the difficulty of a real liaison between literature and visual arts remains total: is it possible to translate literary emotions and inner visions, as only the world of literature is seemingly capable of doing, into the world of the visual arts?

Elusive Material Qualities

Claire Fontaine’s Brickbats are real bricks covered with covers of famous books—which popular language familiarly describes as doorstops—whose artistic fortune has been enduring, with “re-issue” merrily following “re-issue” since their first publication in the early 2000s, filling fairs and exhibitions with their surprise presence. If this piece is a best seller, this is because it combines artistic material with literary material by involving the doorstop as signifier via an especially effective formula. Its success also has to do with the fact that it prolongs the lives of these books which have all marked their day and age in one way or another. The choice of books is not for nothing — Enfance et histoire, French Theory, etc — and their transformation into their sculptural counterpart is part of the extension of a line of thinking where words mean something. Claire Fontaine’s work on these latter does not deny the statement, it underscores it by lending it an explosive, fiery plastic quality, thus ushering in a buried performativeness. So it is with this “Strike” in neon lettering which suddenly lights up when spectators get near. It is quite different with the “doorstops” *, whose performative power remains slightly dormant, but ready to be executed at any moment. The social dimension is also very present in this work, which pinpoints the “illegibility” of these tomes and the distance they introduce in relation to people who are not well-read: artists thus try to reduce this gap by permitting a re-appropriation of it by all and sundry, and all the more powerful because the symbolism of the doorstop as a weapon of rebellion is re-asserted here. All the same, when it is not a matter of total merger between literature and visual arts, the various hijackings of meaning and use that this twosome imbues these volumes with make it possible to “correct” the literature by literally giving it more clout, but, in a way, more levity, too.

Claire Fontaine. French Theory Brickbat, 2009. Brique, fragments de briques, impression numérique sur papier haute qualité / Brick, brick fragments and archival print. 190 × 125 × 65 mm. Courtesy Claire Fontaine. Photo : Claire Fontaine

With Thu Van Tran, we find something of this desire for “rectification” which is at issue in Claire Fontaine’s Brickbats; the book as object is very present in the work of this young Franco-Vietnamese artist, in particular Conrad’s novel The Heart of Darkness, which is re-used twice over, and extended. For Sans tache [Spotless] she has dipped the book in black ink which spills over onto the plaster of a flawless pedestal. The intent comes over right away: it is a question of making the density and the sombre side of the narrative immediately “readable”. The choice of this latter also makes it possible to bring out the post-colonial connotations of an author who is not meant to be part of the usual references, Conrad not being especially associated with an emancipatory stance. A similar treatment had already been envisaged for Duras’s book Écrire, at least with regard to the act of plunging the object into a dye: with Écrire Duras, Thu Van Tran reincorporates in her visual artist’s work a technique which consists in pouring methylene blue over books, making them illegible. The material of massive destruction is thus transformed into pigment, that vital component of the praxis of painting; the book becomes a receptacle, the pages monochrome. But more so than in Sans tache, where, when all is said and done, what is at issue is appropriating the use of an object, it is the piece called Au plus profond du noir [In the Depths of Black] that turns out to be the most intensely linked with the work of a great writer, because the artist here tackles the literary corpus herself, plus its methods of distribution based on its linguistic base, namely: translation. Thu Van Tran has written her own version of Conrad’s narrative, in a simple language, with her very own words. The desire for appropriation is here combined with a wish to overcome the barriers of erudition and distinction usually associated with the masterpiece.

Dora Garcia. The Joycean Society, 2013. Vidéo HD, 53′, version anglaise sous-titrée en anglais ou en français / HD video, 53’, English and French subtitles. Courtesy Dora Garcia ; galerie Michel Rein, Paris.

Daniel Gustav Cramer’s Untitled (Moby Dick) is not far removed from this approach, even if, in it, there is no question either of shattering the logic of the narrative or of calling into question the authority of the translation: the text here is keyed straight out, doing away with page-numbering, paragraphs and any graphic arrangement. The narrative is disturbed in the way it appears: by freeing himself from the pace of paragraphs and word-breaks, and by doing away with all effects, the German artist sheds light on the interdependence between graphic design and readability, between aesthetics and the authority of the “great narrative” which is suddenly altered. What results from this violence is a monster which makes all readings impossible, without the “priming” and the comfort obtained by word processing. This time around, the shift to plasticity happens at the expense of the act of reading, the sculptural element having once and for all destroyed the literary.

W. G. Sebald. Austerlitz, Hanser, Munich, 2001. Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view « L’Image papillon » Photo : Rémi Villaggi.

In the examples given above, we find a renewed interest in the book—as text and object alike—which artists see as raw material which is not quite like other forms of raw material. In the ambivalent homage paid to this object, whose material quality can only be grasped in the light of the immaterial quality for which it acts as medium, there is a mixture of the desire to transgress the authority of the literary opus and the temptation to use the book form without its content, the “primary” narrative, in order to fit it into the field of their own sensibility. As far as the relation between curators and great works of literature is concerned, the same does not necessarily apply. Respect, this time around, seems appropriate, the idea being more to seek liaisons and passages between two disciplines on the face of it impervious to each other.

Joyce, Roussel, Sebald…

Joycean Society is a documentary about the eponymous society founded some thirty years ago with the goal of deciphering James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, deemed to be his most enigmatic work. Dora Garcia’s camera is introduced into one of the meetings which she records in real time. The film starts with an aside about the artist Damien Hirst whom the members do not seem to particularly appreciate, and whom declining ratings—meaning financial—do not seem either to delight or unduly affect, for they seem to consider Hirst is out of sync with present-day society and that his art is disconnected from reality. The more the session advances, the more the seemingly irrelevant opening words seem to be explained, as, little by little, the erudite but joyous interpretation, full of wit and feeling out the society members, shows us the arcana of a text renowned to be elusive for philistines. Scholarly decipherment calls squarely on the intuition of the participants—a delightful gathering of keen-brained seniors, plus a few rather reticent young people full of admiration for their elders—but nevertheless leaves lots of enigmas unexplained. The work seems to be totally attuned to its day, drawing as much from Dublin’s harbour logs as from the Encyclopaedia Britannica—the Wikipedia of that day and age—in which the great writer shamelessly digs to fuel his epic saga, and cuts and pastes impressive lists of nouns and proper names which he reconstructs as he pleases, playing endlessly with language. In some respects, this documentary may seem like a tale that is a tad Manichaean, contrasting success-obsessed artists with people of good will, like the Irish writer whose oeuvre still inspires readings and enthusiasm 70 years after his death. The literary society he depicts does not seem very removed from an ideal society where the words of (old) sages are finally recognized and heard, and where the mix of generations occurs by way of pure intellectual exchanges, with a shared concern for literature: a kind of dream public which seems to leave the director in a dreamy state. One might almost discern here an inexpressible jealousy for an attention paid to literature, as if this latter, unlike the visual arts, was still arousing incomparable empathy.

Is this why we are witnessing a boom in exhibitions involving major literary authors, from Sebald to Joyce [1] by way of Roussel? So why invoke these emblematic works? Is it nostalgia for a time still full of the illusions of modernism which makes them so desirable? Is it the rejection of a ubiquitous materialism which is colonizing art fairs and art galleries, each day deepening a bit further the ditch between the spiritual value of the work of art and its excessive commercialization, that is informing these approaches? But there would not appear to be a single moral design lurking behind the recourse to these works, but a whole host of reasons that are to do with the harnessing of a period—for which literature seems better adapted—as much as the analysis of the fertilizing potential of those outstanding people we call great writers.

In François Piron’s introductory essay to the critical apparatus accompanying the exhibition “New Impressions of Raymond Roussel”, he defends himself against the charge of having wanted to put on a “writer’s exhibition”.[2]

On reading the different contributions making up this volume, we understand a little better what governed the conception of an exhibition gravitating around the figure of Roussel. Far from being just a writer, this latter is above all an inventor who tried his hand in many experimental areas, starting with theatre, which, since his boyhood, he venerated in way that never diminished since. The construction of the Roussellian identity is apparently formed in the manner of a boundless admiration for the oeuvre of Pierre Loti, whom he set at the pinnacle of the literary Olympus; a strange fact for a writer who has remained famous in the world of letters for having created a style of writing that is, at the very least, disembodied, “flat”, and dedicated to the detailed description of things rather than people. Roussel had a profound influence on the work of Duchamp and for this alone he deserves to be celebrated as a pioneer of contemporary art. Why become re-involved in the figure of a writer who died in the late 1930s, over and above a re-appraisal broadly justified by his real significance? His rise in the early 20th century French scene has already been roundly recognized, and one of the merits of “Nouvelles impressions…” is precisely that it shows the influence of the author of Locus Solus beyond national borders, and in its very considerable contemporaneousness. From the outset, the precision of Roussellian writing, brought to a summum, greatly interested his contemporaries. Duchamp first and foremost, for whom what counted most in Roussel was the capacity of his writing to intervene on the very terrain of the image: he was won over by “seeing” the Impressions of Africa at the theatre—and not by reading his books, as Bernard Marcadé recalls [3]. They would influence Duchamp later on when he was making The Large Glass, which he himself described as painting of “precision and meticulousness”. A few decades apart, this time around it would be “a mysterious use of time that Mark Manders has best been able to extrapolate from Roussel’s creative universe” [4], thus referring the anachronisms and asynchronisms of his work to the Roussellian oeuvre. Prior to this, Guy de Cointet, the French expatriate in Los Angeles, had been impressed by “the Roussellian technique of production, using found language and homophony” [5], from which his early stage interventions drew direct inspiration. Mike Kelley, another denizen of L.A.—this one born and raised an American— admits he was attracted by the writer and his games with language; his first performances call de Cointet to mind in his way of assembling phoneme- objects to construct sentences that are grammatically correct, but devoid of meaning. Here again we find the meticulousness of Roussel’s language which, by dint of microscopic, almost scientific description, ends up by losing sight of its object and becoming… poetry. As we can see, Roussellian sequels are many and varied and have to do with dimensions of creation with little relation to each other, ranging from temporal discrepancies to the structure of language that would, in its day, interest the OuLiPo **. To such a degree that it is hard to make out any kind of unity within this paradigm of inspiration. The fact remains that these “time-bombs” which Bernard Marcadé talks about [6] would produce their effect well after Roussel’s death, and we are still awaiting their final explosions.

Mark Manders. Mind Study, 2011. Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view « Nouvelles Impressions de Raymond Roussel » Photo : André Morin.

André Maranha, Pedro Morais, Jorge Queiroz & Francisco Tropa. 3 Moscas, 2012. Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view « Nouvelles Impressions de Raymond Roussel » © ADAGP, Paris 2013. Photo : André Morin.

Winfried Georg Sebald died at the very beginning of the first decade of the 21st century, and ever since his oeuvre has resounded in the field of contemporary art. Nicolas Bourriaud, in the thick of preparing his exhibitions Strates in Murcia, and La consistence du visible at the Ricard Foundation, emphasizes the place occupied by the German writer within his concerns. Sebald perfectly illustrates the theses of the former director of the Palais de Tokyo, which start from the principle that History, with its facts, its events and its bifurcations, forms a big open book, and that the ability to wander around it at will may act as a unifying principle for a whole generation of artists. [7] This “spatialization” of History, as formulated by Sebald, actually lies at the heart of the Sebaldian equation: in the body of his work, this latter involves a comprehensive stroll which intermingles History with its own (hi)stories, and facts of prime importance with his travel anecdotes, never hesitating to overlay the various strata of the narrative, going back over the traces of his predecessors, and drawing both from his own memory and the collective memory. The exhibition on view at the Mudam in Luxembourg until the end of summer, which borrows the title of Muriel Pic’s book, L’image-papillon [The Butterfly- Image], refers to the technique which Sebald used in his last books [8], consisting in inserting images into the flow of the text. This procedure is basically dialectical, as analyzed by Muriel Pic, because, on the one hand, it freezes the memory, borrowing the scientific method’s dimension of collecting and archiving, and, on the other, it links up with the mind’s inclination to pirouette, in an unpredictable and empathetic way, from one memory to the next. The idea behind Christophe Gallois’ exhibition is, here again, to draw inspiration from a literary work imbued with a great complexity. The exercise is quite conclusive insofar as it brings together artists who closely share the writer’s preoccupations. It would seem, however, that the revolutionary character of Sebald’s writing is not completely rendered, for he goes a lot further than entangling narratives and mixing different chords of memory. He brings in nothing less than an ontological break; his writing is not just writing, it shatters the taboo of the joint presence of text and image, and pinpoints “the incompleteness of the text”. In so doing, Sebald goes beyond the field of writing and positions himself on the frontier of film, through “montage”, as Muriel Pic again notes. [9] In fact, just as Roussel, in his day, influenced Duchamp, so Sebald has that writer’s magnetism which dares to exceed the limits of writing, and sows the field of art by once again treading on the terrain of the image. But Sebald’s oeuvre is also permeated by the vision of deeply self-destructive humanity, and his whole literature is oriented towards this unique quest which has him searching through every type of document for the proof of this intuition. [10] The Sebaldian edifice is entirely based on the pursuit of this moral obsession which prompts him to push back the boundaries of the “novel”. The melancholic pitch of his work lies perhaps not for nothing in the seductive power he wields among artists and curators, as well as a faithful population of readers.

- ↑ See in particular the exhibition “Slow Season” of the Mahony collective at La Criée Art Centre in Rennes, and the report in this issue of 02, as a direct response to the general theme of the Frac Bretagne, having chosen as its emblem the figure of Ulysses to celebrate the institution’s 30th anniversary. Many propositions have used the figure of Joyce’s Ulysses, mixing him with Homer’s hero (FRAC Bretagne).

- ↑ Palais n˚17, spring 2013, p. 77, introduction by François Piron.

- ↑ “The vision — or rather the sight — of Impressions of Africa finally convinced Duchamp to move away from the pictorial references in which he had become bogged down (Cézanne, Cubism, Matisse…) », Palais, op.cit., p. 98, article by Bernard Marcadé, “Duchamp / Roussel: various coinciding and tangential points.”

- ↑ Ibid., p. 125, article by Lorenzo Benedetti, “Mark Manders: an experiment in multiplying the present”.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 110, article by Marie de Brugerolle, “Roussel in California: Cointet, Leavitt, Fisher, Kelley…”.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 105, article by Bernard Marcadé, “Duchamp / Roussel: various coinciding and tangential points.”

- ↑ Cf. interview with Aude Launay, 02 n˚47 : interview avec nicolas bourriaud

- ↑ Vertigo, The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz.

- ↑ “Sebald’s literary invention stems from montage, a literary method which Benjamin developed at the cognitive level, whose materialism gives priority to traces”. “Thanks to montage, Sebald offers a vision of the past which is free from chronological logic, because the narratives are constructed through collisions and associations, [and] anachronisms.” in Muriel Pic, L’image papillon, Presses du réel, 2009, p. 13.

- ↑ “Describing realities and destruction, creating awareness about the logic of disaster which governs the history of humankind, is the only valid reason for producing literary work”. Muriel Pic, op.cit., p. 11.

- * Doorstop does not, however, have the nice ambiguity of French pavé, which also means cobblestone, and has distinct overtones of revolution and barricades, as in May ’68.

- ** Standing for Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle, or Workshop of Potential Literature, a loose gathering of (mainly) French-speaking writers and mathematicians, founded in 1960, seeking to create works using writing techniques based on constraints, defined by the group as “new structures and patterns which may be used by writers in any way they enjoy.”

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : Le marathon du commissaire : Frac Sud, Mucem, Mac Marseille, Que sont mes revues devenues ?, Tous migrants ?, Derniers usages de la littérature II, Les chemins de l’émergence 3 : les lieux indépendants,

articles liés

Paris noir

par Salomé Schlappi

Du blanc sur la carte

par Guillaume Gesvret

« Toucher l’insensé »

par Juliette Belleret