Walid Raad, Inside Information

« Préface », Carré d’Art, musée d’Art contemporain de Nîmes, 23.05-14.09.2014, commissariat / curated by : Jean-Marc Prévost

« Postface », University Museum of Contemporary Art, University Massachusetts Amherst, 11.09-7.12.2014

« Prefazione », MADRE, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina, Naples, 11.10.14-19.01.15, commissariat / curated by : Alessandro Rabottini et Andrea Viliani

À venir en 2015 / Upcoming in 2015 : Museum Of Modern Art, New York

On peut voir dans la démarche de Walid Raad, artiste libanais aujourd’hui installé entre Beyrouth et New York, de nombreuses accointances avec ces artistes chercheurs, à la frontière entre historiographie, archéologie, sociologie et anthropologie, ceux qui tentent de réécrire l’histoire, d’en offrir une version alternative, par l’exhumation d’informations et de documents oubliés, négligés ou mal interprétés. Toutefois, une seconde lecture dévoile un processus de travail extrêmement précis et bien plus complexe. Walid Raad mêle à ses investigations et recherches une pratique du storytelling, de la mise en récit, qui donne toute sa singularité à son œuvre. Son projet le plus connu, intitulé The Atlas Group (1989-2004), revient sur l’histoire tourmentée de son pays d’origine. Cette archive, accumulée au fil des années et désormais achevée, même s’il se réserve le droit d’y adjoindre sporadiquement de nouveaux éléments, explore les dimensions sociales, politiques, psychologiques et esthétiques des guerres au Liban. The Atlas Group se veut également une réflexion sur le statut même des documents compilés et sur la transmission de l’Histoire, la manière dont celle-ci peut parfois être manipulée et l’impossibilité d’un récit unique, définitif. Balayons d’emblée la dichotomie fiction / réalité, maintes fois évoquée au sujet de l’Atlas Group, puisque Walid Raad lui-même n’a jamais caché l’inclusion d’éléments totalement inventés dans ses installations. Il s’est emparé de ce procédé pour capter l’attention du regardeur, attiser sa curiosité pour qu’il se renseigne sur la provenance de ce qui lui est donné à voir, les modalités de dévoilement des informations qui lui parviennent. Si les documents de l’Atlas Group ne reflètent pas toujours fidèlement la réalité, c’est bien qu’elle est elle-même suspecte et qu’il n’existe de fait pas une seule version de l’Histoire. En jouant du spectaculaire et de notre propension à l’empathie – chaque série est accompagnée d’un texte qui la contextualise et nous indique sa source –, il parvient à modifier sensiblement notre manière d’aborder ces documents et nous entraîne à rester vigilants au flux permanent d’information.

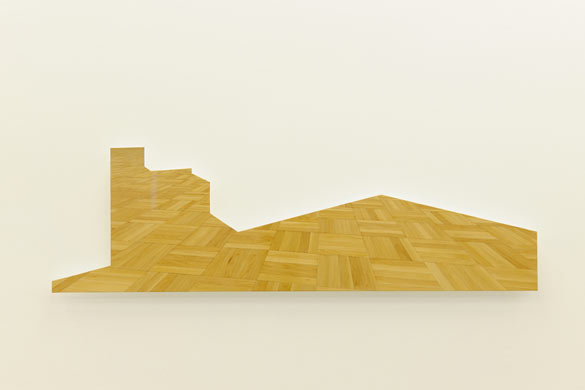

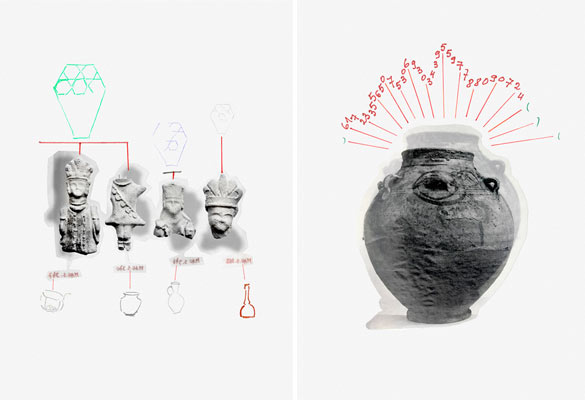

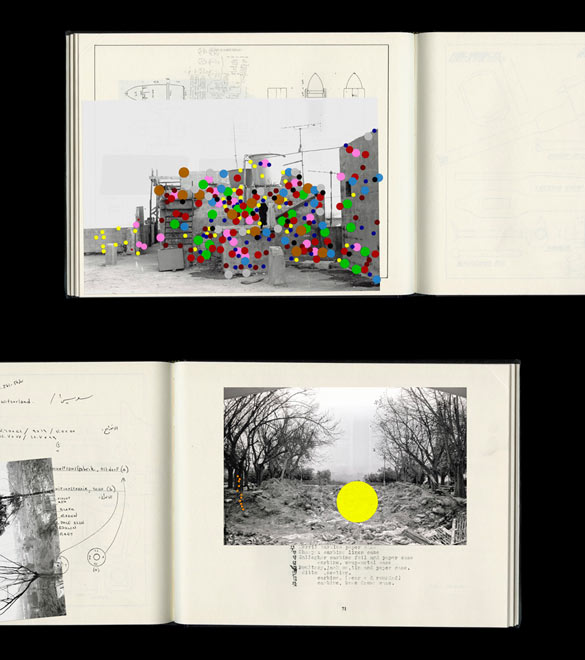

Walid Raad. Preface to the fifth edition _ Plate XII, 2014. Impression jet d’encre (encres archive et papier) / Inkjet print (Archival inks and paper), 41 x 31,2 cm / Preface to the second edition_Plate I, 2012. Impression jet d’encre (encres archive et papier) / Inkjet print (Archival inks and paper), 150 x 200 cm.

Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, le projet sur lequel il travaille depuis 2007, approfondit les recherches engagées avec The Atlas Group et procède du même modus operandi. Mêlant considérations historiques, idéologiques, mais aussi politiques et financières, Walid Raad aborde ici les modes d’apparition d’une nouvelle économie artistique – avec notamment l’émergence du tourisme culturel comme instrument de croissance et de pouvoir économique – et l’implantation prochaine de musées d’envergure internationale dans le monde arabe. Pour ce faire, il convoque de nombreux éléments très disparates qu’il mêle et assemble pour mieux dévoiler les liens ténus entre les sphères culturelle, financière et politique, souligner les nombreux bouleversements qu’entraîne la création de ces « super-structures » culturelles, et s’interroger sur la globalisation du monde de l’art telle qu’elle s’opère aujourd’hui. Walid Raad s’est appuyé sur les écrits de Jalal Toufic, artiste, vidéaste et écrivain libanais d’origine irakienne et palestinienne, qui a développé le concept de « retrait de la tradition suite au désastre démesuré », soit une réflexion sur la manière dont les désastres affectent les traditions. En effet, selon Toufic, « […] la question de savoir si un désastre est démesuré (pour une communauté – elle-même définie par sa sensibilité au retrait immatériel qui résulte d’un tel désastre) ne saurait être tranchée par le nombre de morts ou de blessés, l’intensité des traumatismes psychiques ou l’étendue des dégâts matériels, mais plutôt par ce que l’on rencontre ou non dans son sillage des symptômes de retrait de la tradition. [1] »

I Might Die Before I Get A Rifle_TNT, 1989. Impression jet d’encre (encres archive et papier) / Inkjet print (Archival inks and paper), 160 x 212 cm.

S’emparant de la collection d’art islamique du Musée du Louvre [2] , Walid Raad a littéralement imaginé et mis en forme ce retrait, cette résistance de la part même des œuvres, prêtes à fusionner entre elles pour mieux disparaître. Il a donc créé à l’aide d’imprimantes 3D des objets hybrides, de simples chimères qui se dévoilent à peine, se soustraient à notre regard pour « protester » et témoigner des bouleversements qu’entraîneront la présence de telles institutions dans le paysage culturel et politique moyen-oriental. De même, en soulignant le choix d’architectes occidentaux renommés – parmi lesquels Jean Nouvel, Frank Gehry ou Norman Foster – pour réaliser ces nouveaux musées que sont le Louvre ou le Guggenheim Abou Dabi, Walid Raad revient sur la portée symbolique de telles décisions. N’eût-il pas été plus intéressant de confier ces réalisations à des architectes d’origine arabe, plutôt que de reproduire ce qui a été fait auparavant dans le monde occidental ? N’était-ce pas là l’opportunité d’inventer un nouveau modèle, au lieu de répéter des schémas de pensée que l’on juge aujourd’hui obsolètes ?

Poursuivant son implacable démonstration, Walid Raad se penche également avec Scratching on Things I Could Disavow sur le public potentiel auquel s’adresseront de tels établissements. Dans Section 88: Views from outer to inner compartments_Act VI. 1-5 (2011-2012), il imagine ainsi l’impossibilité pour un autochtone de pénétrer au sein d’un musée fraîchement inauguré, par le biais d’un récit d’anticipation : « Il a simplement l’impression que s’il entre, il va se cogner au mur à tous les coups. Il va littéralement se cogner au mur. Il fait demi-tour sur place pour affronter le flot du public et hurle : “Arrêtez ! N’entrez pas ! Faites attention !” En l’espace de quelques secondes, les agents de sécurité arrivent. Ils le frappent violemment, lui passent les menottes et l’envoient dans une clinique psychiatrique. Le lendemain, j’ouvre le journal, je vais à la page six et je regarde en bas à droite. Je lis ce titre : “Un déséquilibré perturbe l’inauguration. Il prétend que la terre est plate.” [3] »

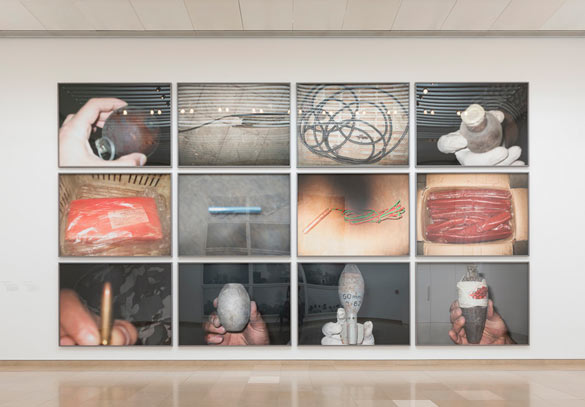

The Atlas Group (1989-2004). I might die before I get a rifle, 1989-2008. Série de 12 impressions jet d’encre / 12 inkjet prints, 160 x 212,5 cm chacune / each. Collection Caixaforum, Barcelona. Photo : David Huguenin © W. Raad.

I Might Die Before I Get A Rifle_Device I et II 1989. Impression jet d’encre (encres archive et papier) / Inkjet print (Archival inks and paper), 160 x 212 cm.

Ce faisant, il laisse à penser qu’avant d’être des initiatives culturelles et humanistes, ces grands chantiers procèdent de décisions politiques dans lesquelles les œuvres ne sont que de simples prétextes et sont instrumentalisées. On pourrait énumérer ainsi les multiples pierres d’achoppement que révèle l’artiste : de l’Artist Pension Trust [4] – ce fonds de pension pour artistes créé il y a maintenant dix ans par un homme d’affaires israélien, à propos duquel l’artiste émet de nombreux doutes – à la collection du musée de Doha, considérée comme la plus grande collection d’art moderne arabe, en passant par la prospérité économique des Émirats Arabes Unis ou la générosité et la philanthropie supposées des cheikhs et cheikhas d’Abou Dabi et du Qatar à l’origine de ces grands projets… Autant d’informations dont s’empare Walid Raad pour témoigner fort justement des dérives de tels investissements, et plus généralement des incertitudes du monde de l’après-11 septembre, nous obligeant à repenser en profondeur certains équilibres géopolitiques.

Le display des deux œuvres évoquées ici, tel qu’envisagé par l’artiste dans sa récente exposition au Carré d’Art de Nîmes, est d’ailleurs particulièrement éloquent. À l’ordonnancement extrêmement rigoureux d’une archive constituée et désormais établie comme celle de l’Atlas Group, proposant une présentation très documentaire et didactique, répond l’énergie du work in progress qu’est Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, soit un ensemble encore fluctuant, déstructuré et amené à évoluer. Rien n’est encore résolu, sur le fond comme sur la forme, mais une telle entreprise semble absolument nécessaire, tant elle soulève de questions sur la légitimité de tels chantiers. S’il est impossible à l’heure actuelle de tirer la moindre conclusion sur ce qu’apporteront ces nouvelles infrastructures, on peut tout de même légitimement s’interroger sur l’opportunité de leur construction. Pour l’heure, parallèlement à Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, l’artiste a entrepris un geste plus directement politique et effectif, en initiant avec d’autres intellectuels la campagne de protestation Gulf Labor [5], afin de dénoncer les conditions de travail déplorables des ouvriers employés sur ces différents chantiers titanesques. Une étape supplémentaire dans l’engagement radical de cet artiste indispensable.

- ↑ Jalal Toufic, « Générique compris », in Le retrait de la tradition suite au désastre démesuré, Paris, Les prairies ordinaires, 2011, p. 11-12.

- ↑ Le Musée du Louvre a invité Walid Raad à une collaboration sur trois années consécutives, qui a débuté en 2013.

- ↑ Walid Raad, « Livre C_ Section 88 : Vue des compartiments internes à externes », in Walkthrough, Londres, Black Dog Publishing, 2014, p. 10.

- ↑ Walid Raad, « Livre B.1_ Les arts de la retraite à Dubaï », op. cit., p. 15.

- ↑ gulflabor.org

Walid Raad, Inside Information

In the approach adopted by Walid Raad, a Lebanese artist who divides his time nowadays between Beirut and New York, it is possible to see numerous connections with those research-oriented artists on the borderline between historiography, archaeology, sociology and anthropology, people trying to re-write history and offer an alternative version of it, by exhuming forgotten, overlooked and poorly interpreted data and documents. However, a second reading reveals an extremely precise and much more complex work process. Walid Raad mixes a storytelling and narrative praxis with his investigations and research, and this lends his work its extremely special character. His best-known project, titled The Atlas Group (1989-2004), returns to the tormented history of the country of his birth. This archive, put together over the years and now complete—even if he reserves the right to sporadically add new elements to it—explores the social, political, psychological and aesthetic dimensions of Lebanon’s wars. The Atlas Group is also intended as a way of thinking about the actual status of the documents compiled and the transmission of History, the way in which this latter can at times be manipulated, and the impossibility of a one-off, definitive narrative. Let us immediately sweep aside the fiction/reality dichotomy, many times referred to in relation to the Atlas Group, because Walid Raad himself has never covered up the inclusion of totally invented factors in his installations. He has appropriated this procedure to catch the onlooker’s attention and attract his curiosity, so that he will inform himself about the provenance of what is being presented to him, and the methods of unveiling the information reaching him. If the documents of the Atlas Group do not always faithfully reflect reality, this is indeed because reality is itself suspect, and because a single version of History does not in fact exist. By playing with the spectacular and with our inclination to empathy — each series is accompanied by a text which contextualizes it and indicates its source for us —, he manages to considerably alter our way of broaching these documents, and prompts us to keep a keen eye on the permanent flow of information.

Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, the project which he has been at work on since 2007, further develops the research embarked upon with The Atlas Group, and proceeds from the same modus operandi. By mixing not only historical and ideological but also political and financial considerations, Walid Raad here broaches the ways in which a new artistic economy is appearing—with in particular the emergence of cultural tourism as an instrument of growth and economic power—and the upcoming establishment of museums of international scale in the Arab world. To do this, he brings in many very disparate elements which he mixes and puts together, the better to reveal the tenuous links between the cultural, financial and political spheres, underscore the numerous upheavals entailed by the creation of these cultural “super-structures”, and raise questions about the globalization of the art world as it is operating today. Walid Raad has relied on the writings of Jalal Toufic, a Lebanese artist, video-maker and writer of Iraqi and Palestinian origin, who has developed the concept of “withdrawal of tradition in the wake of surpassing disaster”, i.e. a line of thinking about the way in which disasters affect traditions. In fact, according to Toufic, “[…] whether a disaster is a surpassing one (for a community— defined by its sensibility to the immaterial withdrawal that results from such a disaster) cannot be ascertained by the number of casualties, the intensity of psychic traumas and the extent of material damage, but by whether we encounter in its aftermath symptoms of withdrawal of tradition. [1] ”

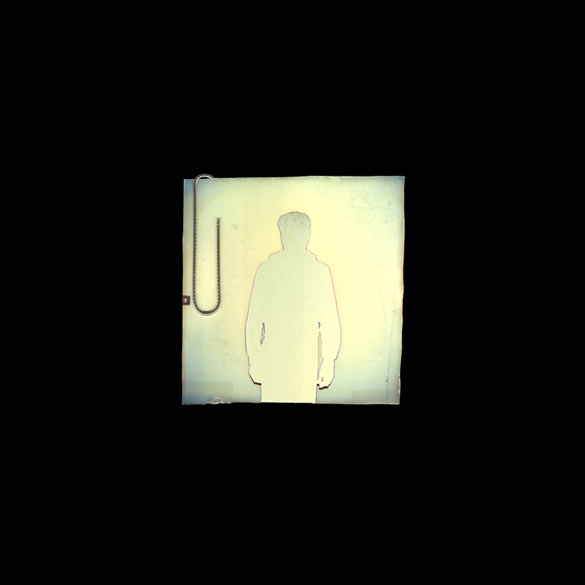

Hostage: The Bachar polaroids _ Plate II, 2001. Impression jet d’encre (encres archive et papier) / Inkjet print (Archival inks and paper), 20,4 x 20,4 cm.

Using the collection of Islamic art of the Musée du Louvre [2], Walid Raad has literally imagined and given form to this withdrawal, this resistance on the actual part of the works, ready to blend together, the better to vanish. With the help of 3D printers he has thus created hybrid objects, simple chimaeras which are barely unveiled, and evade our gaze in order to “protest against” and attest to the upheavals which will result from the presence of such institutions in the cultural and political landscape of the Middle East. Likewise, by emphasizing the choice of renowned western architects—including Jean Nouvel, Frank Gehry and Norman Foster—to build these new museums called the Louvre Abu Dhabi and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Walid Raad reverts to the symbolic scope of such decisions. Would it not have been more interesting to entrust these edifices to architects of Arab origin, rather than reproduce what has already been done in the western world? Was this not an opportunity to invent a new model, instead of repeating patterns of thought that we believed were obsolete today?

Pursuing his relentless demonstration, with Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, Walid Raad also focuses on the potential public which these establishments will address. In Section 88: Views from outer to inner compartments-Act VI. 1-5 (2011-2012), he thus imagines the impossibility for an indigenous person to find his way into a newly inaugurated museum, by way of an anticipatory narrative: “He simply feels that if he walked in, he would certainly “hit a wall”. That he would litterally hit a wall. On the spot, he turns to face the onrushing crowd and screams : “Stop. Don’t go in. Be careful!” Within seconds, the security services arrives. They beat him severely, handcuff him, and send him to a psychiatric facility. The very next day, I open the newspaper, turn to page six, and look at the bottom right-hand corner. I read the following headline: “Demented man Disturbs Opening : Claims World Is Flat. [3] ”

Let’s be honest the weather helped: USA, 1998. Impression jet d’encre (encres archive et papier) / Inkjet print (Archival inks and paper), 46,8 x 72,4 cm / Let’s be honest the weather helped: Switzerland, 1998. Impression jet d’encre (encres archive et papier) / Inkjet print (Archival inks and paper), 46,8 x 72,4 cm.

In so doing, he suggests that before being cultural and humanist initiatives, these great construction projects issue from political decisions in which the works are mere pretexts, and exploited as such. We might thus list the many stumbling blocks revealed by the artist: from the Artist Pension Trust [4] — that pension fund for artists created ten years ago now by an Israeli businessman, about which the artist expresses many doubts — to the collection in the Doha museum in Qatar, regarded as the largest collection of modern Arab art, by way of the economic prosperity of the United Arab Emirates and the presumed generosity and philanthropy of the sheikhs and sheikhas of Abu Dhabi and Qatar at the root of these grand projects… All data which Walid Raad uses to quite rightly illustrate the aberrations of such investments, and more generally the uncertainties of the post-9/11 world, forcing us to deeply re-think certain geopolitical balances.

What is more, the display of the two works mentioned here, as envisaged by the artist in his recent show at the Carré d’Art in Nîmes, is especially eloquent. The extremely rigorous arrangement of a now established archive like that of the Atlas Group, proposing a very documentary and didactic presentation, meets the energy of the work-in-progress represented by Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, which is an ensemble that is still fluctuating, de-structured and bound to evolve. Nothing has yet been resolved, in terms of both content and style, but such an undertaking seems absolutely necessary, because of all the questions it raises about the legitimacy of such construction projects. If it is impossible right now to draw the slightest conclusion about what these new infrastructures will usher in, we can nevertheless legitimately wonder about the advisability of their constructions. For the time being, in tandem with Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, the artist has made a more directly political and effective gesture, by initiating with other intellectuals the Gulf Labor [5] protest campaign, aimed at speaking out against the deplorable working conditions of the workers employed in these various colossal building sites. An additional stage in the radical involvement of this indispensable artist.

- ↑ Jalal Toufic, “Credits Included”, in The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster, Forthcoming Books, 2009, p. 11-12.

- ↑ The Musée du Louvre has invited Walid Raad for a collaborative project over three consecutive years, starting in 2013.

- ↑ Walid Raad, “Book C_ Section 88 : Views from inner to outer compartments”, in Walkthrough, London, Black Dog Publishing, 2014, p. 6.

- ↑ Walid Raad, “Book B.1_ Pension Art in Dubai”, op. cit., p. 1.

- ↑ gulflabor.org

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : Leonor Antunes, Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, Rossella Biscotti, History Repeating, Sterling Ruby, Rosa Barba : Universal Cinema,

articles liés

Iván Argote

par Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

par Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

par Vanessa Morisset