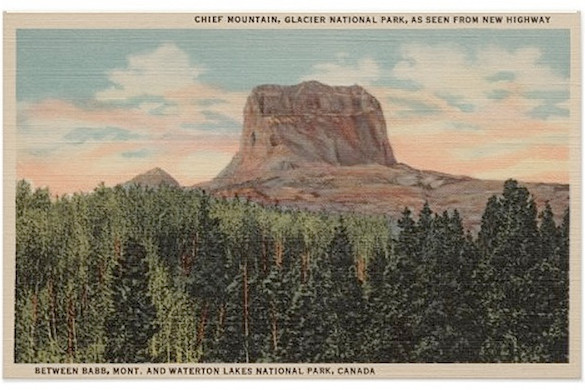

Quand mon cousin a quitté la maison à dix-sept ans, il n’a pas disparu très loin. On peut même penser que ça ne valait pas la peine de disparaître, si c’était pour aller à Lethbridge. Je m’y suis rendu plusieurs fois au cours de mes années d’université à Medicine Hat, parce qu’il fallait bien aller voir ailleurs de temps en temps. Heureusement Donald avait déjà quitté la ville, ce qui m’a évité de le croiser par hasard et d’être terriblement déçu par la destination de sa fuite. Les deux villes sont sensiblement pareilles : des agglomérations sans caractère posées le long d’une rivière dans la Prairie, qui ne doivent leur existence qu’à un sous-sol généreux et à la résignation des Canadiens. La seule vraie différence, c’est qu’à Lethbridge on aperçoit les premiers contreforts des Montagnes Rocheuses. Après des milliers de kilomètres de plat, à peine rythmés de tremblements, l’horizon se relève brusquement au sud de la frontière du Montana, comme un hoquet géologique. C’est le réveil de la croûte terrestre endormie. Et la première forme que dessine ce soulèvement, c’est Chief Mountain.

Tout le temps que mon cousin a passé à Lethbridge, même s’il ne s’agit que d’un an et demi, deux ans grand maximum, il a eu cette proéminence sous les yeux. Et pour quelqu’un qui n’a connu jusque là que les subtiles variations de la plaine, ce pic dressé comme un château a dû rapidement tourner à l’obsession. L’omniprésence de ce volume hirsute représentait une sorte de provocation. L’envie de monter dessus était en tout cas justifiée. La première fois qu’il a essayé d’y aller, il a sûrement été fasciné par la façon qu’a cette montagne de changer de forme, à mesure qu’on s’en approche et qu’on tourne autour. C’est à cause de son relief faussement monolithique, des anomalies de sa structure et des différentes façons dont le soleil éclaire ses flancs. À plusieurs reprises, il a dû vérifier sur la carte que c’était bien la même. Il n’avait jamais vu de vraie montagne, et les collines sont beaucoup plus accommodantes sur leur image.

Pour accéder au versant praticable de Chief Mountain depuis le Canada, il faut passer la frontière et traverser une réserve indienne. Un permis d’accès doit être obtenu, contre dix dollars. Trop de promeneurs laissent traîner leurs déchets, profanent le site avec des beuveries, volent les offrandes qui parsèment le pied de la montagne. On doit aussi donner la raison de sa visite.

Donald connaissait bien le caractère sacré de Chief Mountain. Il savait que, jusqu’à un passé récent, son sommet était voué au rite de passage à l’âge adulte des jeunes Blackfoot. Après la diète et la cérémonie dans la hutte de sudation, la tradition voulait que l’adolescent se rende seul en haut de la montagne, nu et porteur d’un crâne de bison. Cette relique devait être déposée face au soleil levant, pour servir d’oreiller et guider la quête de la vision qui aiderait le jeune à orienter sa vie d’adulte. Et Donald s’était dit intéressé par ces crânes de bisons. On lui avait donc refusé l’accès. Il y avait de bonnes raisons de rire au nez d’un Canadien de dix-neuf ans, étudiant en archéologie, qui convoitait des objets rituels. Dans sa grande naïveté, Donald avait insisté sur l’importance qu’il y avait à recenser et dater ces objets, pour valider leur caractère traditionnel et surtout définir l’origine de cette pratique.

La deuxième fois il était donc revenu avec une lettre d’un de ses professeurs, attestant que les étudiants de premier cycle étaient astreints à un travail de recherche. Il s’était aussi muni d’un appareil photo sensé prouver qu’il s’était résigné à ne rien prélever sur le site. À nouveau, on lui fit savoir qu’il n’était pas le bienvenu. Pour plaisanter on lui dit qu’il ferait bien de se soumettre lui-même au rite de passage : c’était de son âge, et ça lui permettrait peut-être de définir un peu mieux les buts de sa vie. Il n’était pas attendu que Donald soit absolument partant. On lui fit savoir que les dernières générations de Blackfoot ne se livraient plus vraiment à ces pratiques et que, pour une personne extérieure, le prix d’une telle cérémonie s’élèverait à mille dollars. Donald négocia jusqu’à six cent, somme que représentait l’appareil photo de l’université. Il lui suffirait ensuite de le déclarer volé. C’était un des premiers modèles numériques du marché, une nouveauté qui permettait d’enregistrer les fichiers-images directement sur disquette. C’est cet avantage qui fit pencher la balance.

Donald commença immédiatement le jeûne de purification et campa sur place, au pied de Chief Mountain. Les Blackfoot lui avaient proposé un canapé dans un de leurs mobil-homes, mais il préférait se mettre en condition tout seul. En attendant la cérémonie il faisait des promenades dans la réserve, pour observer les offrandes déposées sur des amoncellements de pierres, au pied des arbres ou dans leurs branches. Il s’agissait de morceaux de tissus colorés, de paquets de cigarettes, de clochettes, de coquillages.

Aidé par deux hommes, il coupa et élagua les troncs de douze jeunes saules, qu’il avait d’abord fallut remercier et auxquels on avait expliqué à quoi ils allaient servir, et que d’autres pousseraient bientôt à leur place. Ces troncs furent disposés de façon à supporter un toit fait de bâches et de couvertures, et former ainsi une hutte, dont l’entrée était à l’est. Le lendemain on alluma tôt le matin un grand feu, qui servit à chauffer une quantité de gros galets. On porta ces pierres à l’intérieur de la hutte. De l’eau fut versée dessus. Dehors, Donald tout nu avait été frotté avec des feuilles de sauge et aspergé de terre. Il avait ensuite tourné trois fois autour et pris place dans la hutte, d’un côté du foyer de galets, en face d’un chaman. L’homme agita un bouquet de sauge au-dessus de la vapeur. L’odeur était puissante et il faisait sombre. La peau de Donald ruissela vite de sueur. Le chaman entonna un chant, en frappant sur un tambour les yeux fermés. À intervalles irréguliers il s’arrêtait pour psalmodier, recommençait. Plusieurs fois, d’autres galets brûlants furent ajoutés au foyer. L’éclair du jour par la tente ouverte faisait l’effet d’un lent stroboscope. Le tambour battait aux tympans. À un moment le bouquet de sauge posé sur une pierre commença à se consumer, et l’air devint irrespirable. Personne ne lui avait dit quand il fallait sortir, et mon cousin ne se souvenait ni quand ni comment il avait quitté la hutte. Le soir tombait, il marchait dans une pinède clairsemée, sans chemin. Il était toujours nu, enroulé dans un couverture. Quelqu’un lui avait enfilé ses baskets mais ses lacets étaient défaits. Entre les troncs Donald visait le grand chapeau de Chief Mountain, sans avoir aucune idée de la voie qui le mènerait au sommet. Un instant ça avait l’air facile, l’autre il s’était perdu. Il suffisait de marcher tout droit, par là. Non, demi-tour. Les choses changeaient de place comme si elles s’amusaient. Autour de lui les offrandes suspendues aux branches s’agitaient dans le vent. La montagne se volatilisait et réapparaissait tout près. Ses pas étaient décidés mais son corps hésitant. Il devait aussi s’arrêter souvent pour vomir.

Après avoir dormi, il s’était senti mieux. Le jour se levait et les falaises de Chief Mountain rougeoyaient déjà. Il trouva un passage qui paraissait le mener par la main vers le sommet. Porté par les séquelles de son état second, Donald progressa rapidement. Il voyait des visages dans les formes et les ombres des rochers, des figures graves ou bienveillantes. Il voyait le paysage se rallonger. Il voyait le dos et le dessus des ailes des oiseaux, qui planaient en contrebas et projetaient leur ombre sur les pentes d’éboulis. Le soleil était très haut quand Donald arriva sur la crête. Elle s’étendait en terre-plein accidenté, aride et lunaire. Un peu partout et à différents stades de décomposition, Donald trouva une grande quantité de crânes de bisons. Il passa un moment à errer sur le plateau, zigzaguant de crâne en crâne, fasciné par cette foule d’orbites creuses et de cornes cassées. Il en avait finalement choisi un au hasard et s’était couché, terrassé par la faim et la fatigue. La tête posée sur cet oreiller rituel, il s’était endormi en plein soleil et réveillé sous la lune. Sa bouche était horriblement sèche et ses lèvres gercées. Étendu sur sa couverture, son corps était découvert. Le vent soufflait, Donald avait froid. En remuant pour se couvrir il avait senti une horrible friction irradier sa peau. Son visage, sa poitrine, son sexe et ses cuisses brûlaient d’un immense coup de soleil. Parcouru des premiers frissons de fièvre il s’était calmé en fixant les étoiles le plus longtemps possible. Son corps s’enfonçait dans le sol, pressé par le flux de leurs rayons. Certaines s’étaient mises à vibrer excessivement, mais c’était normal : des piliers devaient être définis. Ils plongeaient doucement du cosmos, comme d’immenses stalagtites lumineuses. Ce qui était plus inquiétant c’était que les étoiles-commandantes discutent comme ça entre elles, des chuchotis incompréhensibles, des secrets qui concernaient forcément Donald. Petit à petit, il devenait clair qu’elles avaient à son égard de grandes exigences. Ça ne servait à rien d’essayer de leur parler, elles ne se laisseraient jamais convaincre.

Le lendemain mon cousin se réveilla à l’aube, ce qui lui permit de soulager son insolation avec des pierres froides. Il lécha aussi toute la rosée qu’il put. Pendant le reste de la matinée il resta assis à l’ombre d’une tourelle rocheuse, mâchonnant des herbes pour distraire sa faim. Il dormit une bonne partie de l’après-midi, d’un sommeil malade. En fin de journée il fit le tour du plateau. Les crânes de bisons s’avérèrent décevants : à part leur disposition régulière face à l’est, leur piteux état de conservation ne permettait de tirer aucune conclusion. En revanche, Donald était ébahi par l’ampleur des points de vue. Le spectacle étranger des Rocheuses, la totalité de la chaîne Lewis, Duck Lake et Goose Lake, le tracé des rivières et des routes. La Prairie était évidemment là, mais à cette hauteur il ne la reconnaissait pas aussi bien qu’il aurait dû. Vue d’ici, son étendue avait quelque chose de catastrophique. Très loin vers l’est, au-dessus d’un cours d’eau qu’il identifia comme la Milk, des éclairs intranuageux clignotaient en silence. La menace d’un orage sur une crête si exposée le rendit impatient de partir. Convaincu par son état de faiblesse plus que par la quête des visions, il passa quand même encore une nuit au sommet. Mais cette fois, plutôt que d’insister avec les crânes de bisons, il s’arrangea un oreiller avec ses baskets.

Le troisième jour, comme personne n’était encore venu le chercher, mon cousin redescendit tout seul de la montagne. Arrivé au parc des mobil-homes il demanda à voir le chaman pour obtenir une interprétation de son expérience, mais on lui dit qu’il était en séance au bureau des affaires indiennes et serait absent pour la journée. Donald récupéra ses habits chez l’un des hommes qui l’avaient aidé à construire la hutte. L’homme lui proposa de prendre une douche et de le rejoindre dans la cuisine, où il lui prépara des œufs. En mangeant un paquet entier de pain de mie, Donald discuta avec lui de sa vision, des piliers célestes et des étoiles qui complotaient. L’homme estima que les signes n’étaient pas très clairs, et lui conseilla sobrement de poursuivre sa quête.

(Cette fiction de Jérémie Gindre est publiée à l’occasion de Camp Catalogue, l’exposition de Jérémie Gindre à La Criée, Rennes, du 12 juin au 16 août 2015, produite en collaboration avec la Kunsthalle de Mulhouse (FR) et Kiosk, Gand (BE))

When my cousin left home at the age of 17, he did not go very far. One might even be forgiven for thinking that it was not really worth the trouble of disappearing, if it was just to go to Lethbridge.

I went there several times during my university years at Medicine Hat College, because it was important to see somewhere else from time to time. Luckily Donald had already left the city, which meant I would not bump into him by chance, and be terribly disappointed to discover his destination. The two cities are quite alike: characterless built-up areas lying along a river in the Prairie, which owe their existence to nothing more than a generous subsoil and the resignation of Canadians. The only real difference is that, in Lethbridge, you can glimpse the first spurs of the Rockies. After thousands of flat miles, barely punctuated by tremors, the horizon rises up abruptly south of the Montana border, like a geological hiccup. This is the awakening of the slumbering earth’s crust. And the first shape that this upheaval forms is Chief Mountain.

Throughout the time my cousin spent in Lethbridge, even if it was only a year and a half, two at the most, he had this protuberance before his eyes. And for someone who, up until then, had only known the subtle variations of the plains, that peak soaring skywards like a castle must quickly have become an obsession. That hirsute omnipresent volume represented a kind of provocation. The desire to climb up it was in any case justified.

The first time he tried to go there, he was certainly fascinated by the way that mountain can change shape, as you approach it and go round it. This is due to its falsely monolithic relief, anomalies in its structure, and the different ways the sun lights up its slopes. On several occasions he had to check on the map that it was indeed the same mountain. He had never seen a real mountain, and hills are much more obliging with their image.

To reach Chief Mountain’s accessible side from Canada you have to cross the border and go through an Indian reservation. You have to get a permit, which costs $10. Too many hikers leave their rubbish behind, desecrate the site with drinking binges, and steal the offerings scattered at the foot of the mountain. We should also explain the reason for his visit.

Donald was well aware of the sacred character of Chief Mountain. He knew that, until quite recently, its summit was sacred in the coming-of-age rite of passage of young Blackfoot men. After the fasting and the ceremony in the sweat lodge, tradition dictated that the adolescent should climb alone to the top of the mountain, naked and carrying a bison’s skull. This relic had to be placed facing the rising sun, acting as a pillow and guiding the quest for vision which would help the young man to give direction to his adult life. And Donald had expressed an interest in those bison skulls. As a result, he had been refused access. There were good reasons for laughing in the face of a 19-year-old Canadian, studying archaeology, who coveted ritual objects. In his great naivety, Donald had gone on about the importance of listing and dating those objects, to confirm their traditional character and, above all, define the origin of that practice.

So the second time he returned bearing a letter from one of his professors, certifying that first year students had to have a field research. He also had a camera with him, which was meant to prove that he agreed not to remove anything from the site. Once again, they let him know that he was not welcome. As a joke, they told him it would be a good idea if he underwent the rite of passage himself: he was the right age, and that would perhaps help him define the goals of his life a bit better. They did not expect Donald to be so completely game. They told him that the last few generations of Blackfoot no longer really got involved in those practices, and that, for someone from outside, the price for such a ceremony was $1000. Donald got them down to $600, the price of the university’s camera. All he would have to do was say it had been stolen. It was one of the first digital models on the market, a novelty that made it possible to record image-files straight on a floppy disk. It was that advantage which tipped the scales.

Right away, Donald started the purifying fast and camped on the spot, at the foot of Chief Mountain. The Blackfoot offered him a sofa in one of their mobile homes, but he preferred to prepare himself on his own. While he waited for the ceremony, he took walks in the reservation, noting the offerings placed on small piles of stones, at the foot of trees, or in their branches. The offerings were bits of coloured fabric, packets of cigarettes, small bells, and shells.

Helped by two men, he felled and pruned twelve young willows, which he had first had to thank, explaining what they were going to be used for, and that others would soon grow where they had stood. Those trunks were arranged in such a way as to support a roof made of tarpaulins and blankets, thus creating a hut, with its entrance to the east. Early next day, a large fire was lit, and used for heating many large stones. Those stones were carried inside the hut. Water was poured over them. Outside, stark naked, Donald had been rubbed with sage leaves and sprinkled with earth. He had then spun round three times, and taken his place inside the hut, beside the hearth of stones, facing a shaman. The man waved a bunch of sage above the steam. The smell was strong and it was dark. Donald’s skin was soon dripping with sweat. The shaman started chanting, beating on a drum, eyes closed. At irregular intervals he stopped to drone, and then started chanting again. Several times, more burning stones were added to the hearth. The daylight coming through the door had the effect of a slow stroboscope. The drum hurt his eardrums. At one moment, the bunch of sage placed on a stone started to burn, and the air became stifling.

No one had told him when to go outside, and my cousin could not remember when or how he had left the sweatlodge. Night was falling as he walked through a sparse pine wood, where there were no paths. He was still naked, wrapped in a blanket. Someone had put his sneakers on for him, but the laces were undone. Between the tree trunks Donald could see the great hat of Chief Mountain but he had no idea what trail would take him to the top. One moment it looked easy, the next he felt lost. All he had to do was walk straight ahead, that way. No, he retraced his steps. Things changed places as if they were having fun. Around him offerings hanging from branches swung in the wind. The mountain vanished and then re-appeared, very close. His steps were resolute, but his body was hesitant. He also often had to stop to vomit.

After sleeping, he felt better. The day was dawning and the crags of Chief Mountain were already turning red. He found a path which seemed to pull him by the hand towards the summit. Borne along by the after-effects of his daze-like state, Donald advanced fast. He saw faces in the shapes and shadows of rocks, figures which were solemn, or kindly. He saw the landscape lengthen. He saw the backs and the tops of the wings of birds gliding below him, casting their shadows on the scree-filled slopes. The sun was very high when Donald reached the ridge. It stretched away through a hilly expanse, arid and lunar. Here, there and everywhere, and in differing stages of decomposition, Donald found a large number of bison skulls.

For a moment he wandered over the plateau, zigzagging from skull to skull, fascinated by that throng of hollow eye sockets and broken horns. He finally chose one at random and lay down, overcome by hunger and tiredness. With his head on that ritual pillar, he fell asleep in the sun, and woke up beneath the moon. His mouth was horribly dry and his lips chapped. Lying on his blanket, his body was uncovered. The wind blew, Donald was cold. As he moved about to cover himself, he felt a nasty rubbing sensation spread across his skin. His face, chest, genitals and thighs were all scorched by sunburn. After the first feverish shivers, he calmed down by staring at the stars for as long as possible. His body sunk into the ground, squeezed by the flow of their rays. Some of them had started fiercely vibrating, but that was normal: pillars had to be defined. They dived slowly from the cosmos, like huge glowing stalagtites. What was more disconcerting was that the stars in command should talk like that among themselves, incomprehensible whisperings, secrets which had to do with Donald. Little by little it became obvious that they had great demands in his regard. It served no purpose to try and talk to them, they would never let themselves be persuaded.

Next day my cousin awoke at dawn, which meant that he could relieve his sunstroke with cold stones. He also licked up all the dew he could. For the remainder of the morning he stayed sitting in the shade of a turret of rock, chewing grass to relieve his hunger. He slept for much of the afternoon, a sick sleep. At the end of the day he walked round the plateau. The bison skulls turned out to be disappointing: apart from their regular arrangement facing east, their pitiful state of conservation meant that no conclusions could be made. On the other hand, Donald was astounded by the range of viewpoints. The strange spectacle of the Rockies, the entire Lewis Range, Duck Lake and Goose Lake, the courses of rivers and roads. The Prairie was obviously there, but at that height he did not recognize it as well as he should have. Seen from here, the expanse of it could make one think of a disaster. Far off to the east, above a river that he identified as the Milk, there were silent flashes of lightning between the clouds. The threat of a storm on such an exposed ridge made him impatient to leave. But all the same he spent another night at the summit, persuaded to do so by his weak state more than the quest for visions. But this time, rather than insisting on bison skulls, he made a pillow for himself with his sneakers.

On the third day, since nobody had as yet come looking for him, my cousin climbed back down the mountain on his own. When he reached the mobile home park, he asked to see the shaman for an interpretation of his experience, but he was told the shaman was at a meeting at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and would be away the whole day. Donald retrieved the clothes he had left with one of the men who had helped him make the lodge. The man invited him to have a shower and join him in the kitchen, where he cooked eggs. While he scoffed a whole pack of white bread, Donald told him about his vision, the celestial pillars and the stars plotting. The man thought that the signs were not very clear, and soberly advised him to continue his quest.

(This short story by Jérémie Gindre is published on the occasion of Camp Catalogue, the solo show of Jérémie Gindre at La Criée, Rennes, from June 12 to August 16 2015, produced by La Criée centre for contemporary art, in partnership with La Kunsthalle, Mulhouse (FR) and Kiosk, Gent (BE))

articles liés

Iván Argote

par Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

par Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

par Vanessa Morisset