Florian Pugnaire et David Raffini, Théâtre des Opérations

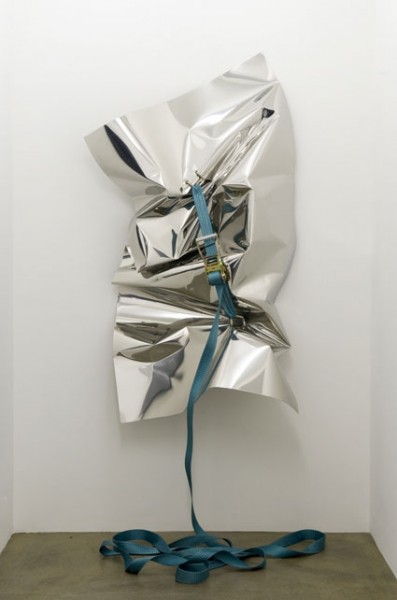

Toiles lacérées à la sangle, voitures et machines à l’épreuve de la compression : la mécanique de destruction à l’œuvre chez Florian Pugnaire et David Raffini a de prime abord un air de famille avec le Nouveau Réalisme. À y regarder de plus près, cette stratégie de destruction s’inscrit dans le processus de fabrication de l’œuvre ; l’action performative et le geste en conditionnent l’apparition.

Qu’ils s’attaquent à une Fiat 126, une 2 CV ou un tractopelle, la machine devient une sculpture hybride qui a enregistré les accidents volontaires.

Hors Gabarit (2010) prend pour point de départ une Fiat 126 également surnommée Polski Fiat, une voiture pour le peuple, d’abord produite en Italie puis choisie comme telle aussi par le régime polonais. Sa carcasse est enfermée dans une grande sculpture minimale en tôle d’inox que l’on ne verra qu’en photographie. Les artistes tentent alors avec force coups de masse, et à l’aide de sangles et d’une presse hydraulique, de retrouver le gabarit initial du véhicule : le remodelage s’effectue ainsi à la fois manuellement et mécaniquement. La compression est ici paradoxale : elle ne vise pas à transformer radicalement l’objet mais à redonner à un produit industriel reproductible un semblant de forme originale. De ce processus de destruction naît une forme unique. La sculpture s’inscrit dans la tradition de ce que l’on pourrait appeler la « vanité automobile » amorcée dans les années 1960, dans la lignée des Car Crashs d’Andy Warhol, de la Giulietta de Bertrand Lavier ou des compressions de César caractérisées par l’usage de la presse hydraulique.

Florian Pugnaire / David Raffini Vues de l'exposition Hors Gabarit photographies Aurélien Mole Courtesy galerie TORRI, Paris

Tout comme Expanded Crash, qui voyait une 2 CV subir une compression programmée dans la durée (de juin 2008 à mars 2009), In Fine repose sur un principe d’auto-destruction.

Une épave de tractopelle biélorusse a été importée dans la friche du Palais de Tokyo. Seule en scène, la machine s’autodétruit progressivement dans un étrange ballet mécanique, ses griffes projetant leur ombre sur la coupole et rappelant subrepticement La Fourchette (1928) d’André Kertesz — ce leitmotiv de la griffe sur fond blanc apparaissant également dans La Maison du Docteur Edwards (1945) d’Alfred Hitchcock. Lorsque la machine déraille, c’est l’ère industrielle qui s’emballe avec elle. La performance a donné lieu à un film éponyme qui voit le paysage de catastrophe contaminé par la ruine et la désolation ressembler étrangement à celui de Tchernobyl : la machine courant à sa propre perte devient un hybride monstrueux entre le mécanique et l’organique. Dans la vidéo-performance Manœuvres (2009), c’est un Fenwick qui se met à décrire des cercles sur le sol d’une usine ; ce travelling piloté par la machine (une presse de dix-huit mètres de long) dessine alors un théâtre des opérations où les objets sont progressivement soumis à la destruction.

Froisser, pulvériser, broyer, concasser, marteler, déchirer la tôle ou la toile sont autant de modalités de destruction qui permettent à l’action d’engendrer l’œuvre, embarquant les objets dans une histoire qui s’éloigne progressivement de celle du ready-made.

Florian Pugnaire and David Raffini

Theatre of Operations

by Audrey Illouz

Canvases slashed with a strap, vehicles and machines subjected to compression tests: at first glance, the mechanics of destruction at work with Florian Pugnaire and David Raffini has a family look about it, involving New Realism. On closer inspection, this strategy of destruction is part and parcel of the process of making the work; the performance-related action and the gesture condition its appearance.

Whether they are attacking a Fiat 126, a Citroen 2 CV or a backhoe loader, the machine gives rise to a mongrel sculpture which records deliberate accidents.

Hors Gabarit/Heavy Vehicles (2010) takes as its starting point a Fiat 126 also nicknamed Polski Fiat, a car for the masses that was first produced in Italy, before being selected by the Polish government as the people’s car. Its body is enclosed inside a large minimal sculpture made of stainless steel sheets, which is only ever seen in photographs. Then, with sledgehammers, straps and a hydraulic press, the artists try to re-find the vehicle’s initial size: the remodeling is thus carried out both manually and mechanically. The compression here is paradoxical; it is not aimed at radically transforming the object, but at restoring to a reproducible industrial product a semblance of its original form. From this process of destruction a unique form comes into being. The sculpture is part of the tradition of what we might call the “automobile vanitas”, ushered in in the 1960s, in the wake of Andy Warhol’s Car Crash works, Bertrand Lavier’s Giulietta, and César’s compressions hallmarked by the use of a hydraulic press.

Just like Expanded Crash, which saw a Citroen 2 CV undergo a time-programmed compression (from June 2008 to March 2009), In Fine is based on a principle of self-destruction. A wrecked Belorus backhoe loader has been brought into the waste ground of the Palais de Tokyo. Alone on stage, so to speak, the machine gradually destroys itself in a strange mechanical ballet, its claws casting their shadow over the cupola and surreptitiously calling André Kertesz’s La Fourchette/The Fork (1928) to mind—this leitmotiv of the claw on a white ground also appearing in Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945). When the machine goes off the rails, it is the industrial age that goes along with it. The performance has given rise to an eponymous film which sees the landscape of catastrophe contaminated by ruin and desolation look strangely like that of Chernobyl: the machine hurtling to its own destruction becomes a monstrous mongrel somewhere between the mechanical and the organic. In the performance video Manoeuvres (2009), it is a fork-lift truck that starts making circles on the floor of a factory; this tracking shot, steered by the machine (a 60-foot long press) thus outlines a theatre of operations where the objects gradually undergo destruction.

Crumpling, pulverizing, crushing, grinding, hammering, and ripping sheet iron and canvas are all methods of destruction which permit action to give rise to the work, embarking the objects involved on a story which gradually gets further and further away from that of the readymade.

articles liés

Iván Argote

par Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

par Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

par Vanessa Morisset