When the Inconceivable Takes Form at the Cité Internationale des Arts

From 7 June to 12 July 2023

Exhibition curated by: Oksana Karpovets

Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris-Marais

The exhibition is organised in partnership with Portes Ouvertes Sur l’Art

Imagine a monumental statue in a Ukrainian city, in the middle of a fountain. The national poet, king or some kind of allegory occupies the space like a human body, and almost looks as if it could raise an arm or bend over. In contrast, the four-metre-high monument in front of us, on a pool of water, is difficult to understand. Not that it is abstract: in fact, its limbs are very realistic, and one can clearly make out a foot, a navel and a mouth, all arranged as in a human body. But it is mounted vertically in hanging fabrics onto which fragments of bodies filmed in a shower are projected.

The ancient legend of Zeuxis, who is said to have painted Helen by combining the features of the most beautiful women of Crotone, already pointed out that any representation is a synthesis of elements that are in reality separate. But the video installation Filling the Endless (2023) by the Ukrainian artist Sergiy Petlyuk suggests that war makes us stop identifying with the whole to which we have given these elements: without separating from the collective body, each individual reclaims his or her own pain – which has become too big for the space allotted to it. Rather than Zeuxis, we are closer to Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad (2013), in which bits of corpses woven together by a ragpicker produce a monster that wanders the city in search of new pieces from those who killed the elements that make it up. In Petlyuk’s installation, too, the national body is in short supply, less than the sum of its parts. Each member is squeezed into a fixed close-up, breathing and exhaling in slight asynchrony with the others. These figures without an exterior form a body that can neither raise an arm nor go down to greet the citizens: its only way of moving would be to burst.

In the context of the exhibition “When the Inconceivable Takes Form” – which brings together some fifteen artists from Ukraine, Iran, Lebanon, Myanmar, Belarus and Syria and its occupied Golan Heights – Petlyuk’s installation takes on a broader meaning. By inviting artists who represent political violence without showing it, curator Oksana Karpovets (a Ukrainian art historian and resident at the Cité des arts) has taken it upon herself to translate the catastrophe into a question of form. It is not, therefore, a cathartic exhibition, one that has been seen over and over again, from which the French viewer would emerge secretly relieved to be outside the tragedies of others. Although it seems to be the shortcut that brings these artists together, the label ‘victim’ doesn’t fit very well, and the human figure is rare. The works need to be confronted with each other and appear to be solutions to a problem of representation.

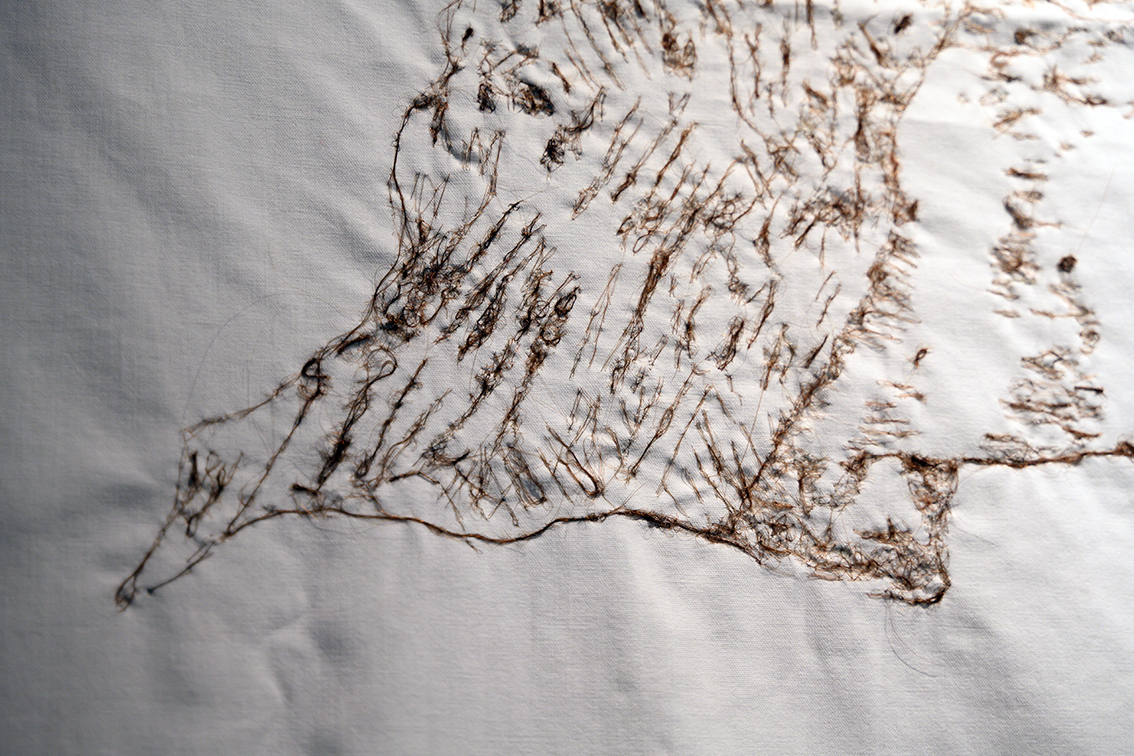

These solutions are conditioned by their contexts. The introduction of bodily intimacy into the national sphere (and vice versa) has been a key strategy in Ukrainian art at least since the Kharkiv School of Photography: this interest persists in Petlyuk’s work, but also in Yana Bachynska’s Banner for Biopolitics (2017), a delicate silhouette of a flag embroidered on a sheet with the artist’s hair. As for the Arab context, it shows a concern for the conditions of (in)visibility of the victims – a concern that is perhaps stems from the old obsession with Orientalist voyeurism and its current media extensions. Syrian artist Akram Al Halabi’s Cheek series (2011-2017), for example, replaces the broadcast images of the victims with floating descriptive annotations, as fragmented as Petlyuk’s, but which conceal the bodies while signifying them.

And it is in the installation by Lebanese artists Rana Haddad and Pascal Hachem, Debris of Texts and Eyeglasses (2022), that the question of visibility is particularly poignant. We find ourselves in the middle of a circle of thirty frames suspended from above, each containing a sample of debris wrapped in a white sheet of paper and therefore barely visible, as well as a photograph of damaged glasses. These two types of record of the Beirut explosion (2020) are presented with the impassivity of a criminologist and function as an allegory of the very impossibility of representing such an event. Glasses, like art, are the fragile screen that both establishes a protective distance between us and reality and makes it more visible. But these pieces of debris are indecipherable, and their juxtaposition with the mutilated glasses suggests that to see them is to cross over to the other side of representation – as was the case for the wearers of the shattered spectacles, who, from their initial position as viewers, suddenly merged with reality during the explosion. Some of the glasses are replaced by quasi-transparent words written on the glass of the frame, casting their barely legible shadows on the wooden background, activating the same now dysfunctional screen between reality and our perception.

This conceptualist approach inherited from the 1970s (which borders on the sublime in Haddad’s other work, Disintegration/Making Of (2021)) coexists with a more documentary approach typical of the last twenty years: we find it in Marwa Arsanios’ short film Who is Afraid of Ideology? Part 1 (2017) about the autonomous Kurdish women’s movement, or in Ephemeral Shelters, Transformed Places (2019-2023) by the Iranian artist Bahar Majdzadeh, who uses photos, maps and testimonies to document public spaces in the Paris region that were once occupied by migrant camps before they were evacuated.

The unexpected inclusion of the Ile-de-France landscape in this catalogue of devastation undermines the distinction between ‘where the misery is’ and a ‘here’ outside that merely suffers the symptoms. The chain is not so complicated: the elected representatives of French men and women sell arms, for example to Saudi Arabia, the latter massacres Yemenis who then seek refuge in Paris or Saint-Denis, and the former prevents them from settling there with a hostile architecture of concrete, flowers and skate parks. The visitor, whose taxes may have contributed to these constructions, can admire them in Majdzadeh’s photographs as almost abstract sculptures in which traces of fabric or a boot remain (look a second time!), traces left by the invisible inhabitants.

The ‘inconceivable’ to be formulated would therefore not be just an explosion here or a camp there, but something like the order of causality between the two, or at least their inevitable interweaving within the same global system that produces them. The reunion of these works was thus achieved not through a common and eternal positioning as ‘victim’, but through a desire to think as the totality of a condition that is both fragmented and united. Like Petlyuk’s body(ies), it has no exterior from which a pure spectatorship can exist that is never, if only for a moment, threatened with becoming an accomplice.

______________________________________________________________________________

Head image : Yana Bachynska, Banner for Biopolitics, crédit pour les photographies : cité internationale des arts © Eva D Photographie

Related articles

Yoshitoro Nara at Guggenheim, Bilbao

by Guillaume Lasserre

Moffat Takadiwa

by Andréanne Béguin

Alias at M Museum, Leuven

by Vanessa Morisset