Erin Gleeson

Erin Gleeson is a freelance curator based in Phnom Penh. In 2011 she co-founded with the collective Stiev Selapak artists, SA SA BASSAC at which she is the artistic director. SA SA BASSAC is a non-profit art space including a gallery and reading room, and a curatorial platform for exchange programs and research. It works in conjunction with the activities of Sa Sa Art Projects, run by the same group and led by artist and curator Vuth Lyno. Sa Sa Art Projects is dedicated to experimental residency and educational practices in a community-based environement of the apartment bloc known as White Building, which remains one of the few architectural projects of the Independence era cultural district “Bassac River Front”. Erin Gleeson is currently guest curator of Satellite program of the Jeu de Paume in Paris and CAPC in Bordeaux entitled “Enter The Stream At The Turn” for which she invited the artists Khvay Samnang, Nguyen Trinh Thi, Vandy Rattana and Arin Rungjang.

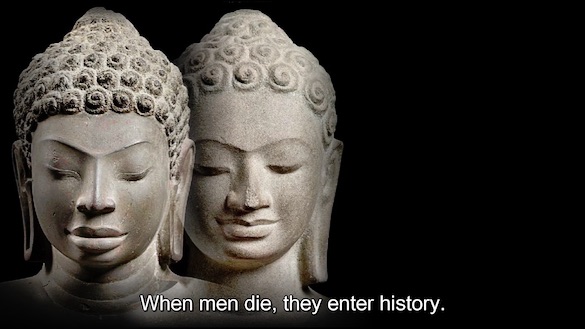

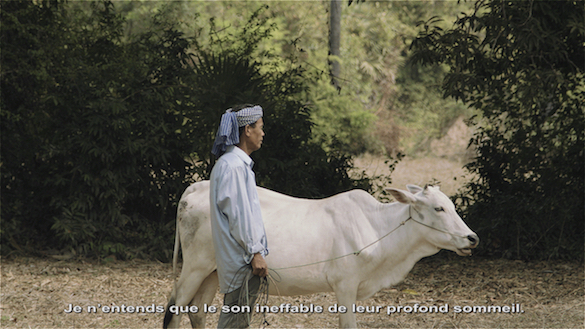

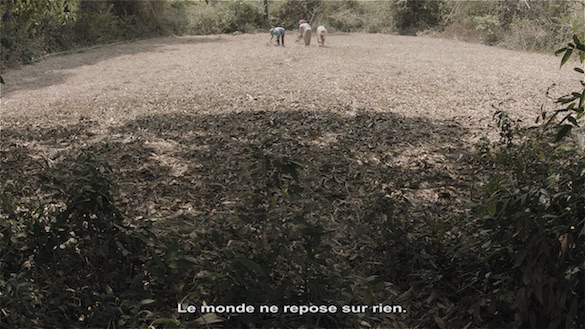

Ngyuen Trinh Thi, Letters from Panduranga, 2015. HD Video, 36′. Co-produced by Jeu de Paume, Paris ; Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques ; CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux. Courtesy Ngyuen Trinh Thi © Ngyuen Trinh Thi, 2015.

How did you end up working in Cambodia?

I come from Minneapolis in Minnesota, though by now I’ve spent around half of my life elsewhere. While a “professional” career began in Cambodia, indeed my “pre-Cambodia” life is full of important references for me today. I studied in Minnesota as well as in South Africa in the late 1990s, majoring in Art, Art History and Peace and Conflict Studies simultaneously – subjects I thought naturally belonged together. At that time, I had overlapping visions about being an artist and educator involved in thinking and making together with people living in “post-conflict” areas. I chose to learn at a Catholic-but-ecumenical, stunning Marcel Breuer-built campus in the middle of secluded forest and wetlands. I was not raised Catholic but I was attracted to its monasticism and the Benedictine mantras of hospitality and community living, and an idealism around participation. In courses I was introduced to Cambodia from different angles, from ancient pottery and architecture to Khmer Rouge era photography, the later was the topic of my thesis. My interest was not only Cambodia; the “Asian Studies” department drew me to projects like with the Minneapolis Institute of Arts where I wrote the education guide to the Islamic collection for example. As the assistant to the director to the four campus galleries for four years, I began organizing exhibitions and educational programs. The university has a rich collection; I remember my excitement at 18 years old to be preparing original Albers Homage to the Square and prints by Picasso and Chagall for example. There were also influential collaborations including with local gallerist Todd Bockley who works primarily with indigenous artists and photographer Wing Young Huie who worked initially focused on the diverse Asian populations in Minnesota including Hmong, Vietnamese and Cambodian – Minnesota was the third largest home to Cambodian diaspora in the US. I received a Jerome Foundation grant to work with the United Cambodian Association of Minnesota, facilitating photography workshops with the elder and younger generations. At the same time I was also working at the Walker Art Center in the Atelier Van Lieshout’s mobile art lab which the Walker commissioned as a youth center on wheels that could “bring the good word of art and culture” to schools poorer neighborhoods. I have to say the Walker has been one of my major “teachers” – its curatorial and graphic design practice and especially its ongoing, committed relationships with artists and its inclusiveness of performance practices from the beginning. Recently, Nguyen Trinh Thi, (the final artist to exhibit in the Satellite 8 program) said to me “As artists we have the desire to be engaged but also to disappear.” I think maybe a lot of these experiments when I was younger were attempts to resolve this tension – to find poetry as the means of participation, engagement, resistance.

How did you initially get to know the Cambodian art scene?

In terms of directly going to Cambodia for the first time, it was in 2002 through a Fulbright fellowship from the Human Rights Center of the University of Minnesota Law School. For my thesis research, I first met Vann Nath (1946-2011), the incredible man and painter who survived S-21 prison. I volunteered with the Cambodian Institute of Human Rights for “fieldwork” focusing on creative methodologies in human rights education. During that experience, I was offered to teach undergraduate elective Art History courses at the new liberal arts university in Phnom Penh. I began with a generally sweeping East-West comparative course, during which I thankfully learned to re-reconsider canons by listening to students read the works without context as an exercise in looking, seeing. Ten years later, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Village and Elsewhere and Two Planets video series from 2012 resonated with my experiences in that course. Araya had placed reproductions of iconic Western paintings in everyday settings in Thailand and invited people from the community to respond to the works, revealing both amazingly different and surprisingly similar readings of the works as were originally intended. I rearranged curricula for each semester attempting to be more ‘useful’ for students, and it was during the semesters dedicated to engaging with Cambodia’s living artists that I initially became engaged. The students and I immersed ourselves in the Phnom Penh visual arts context as much as we could, visiting studios and joining every exhibition opening was a manageable task – even today in a small ‘scene’. As the exhibition contexts we visited were all co-founded by foreigners or foreign-Cambodian diaspora partnerships in the previous decade, I thought it was also important to consider indigenous visual cultures outside of the art scene – spaces where visual languages have rich histories and everyday significance, so for example we went to mosques and pagodas and had discussions with Cham imams and Buddhist monks. Yet back then, as an artist, writer and teacher, my friendships with artists initially had no curatorial premise; I did not plan to make exhibitions in Cambodia, and regardless there were and still are few established roles for curators in the country.

Vandy Rattana, MONOLOGUE, 2015. HD Video, color, sound, 18’55.

Co-produced by Jeu de Paume, Paris ; Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques ; CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux. Courtesy Vandy Rattana © Vandy Rattana, 2015.

Vandy Rattana, MONOLOGUE, 2015. HD Video, color, sound, 18’55.

Co-produced by Jeu de Paume, Paris ; Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques ; CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux. Courtesy Vandy Rattana © Vandy Rattana, 2015.

Can you talk about how you then became involved in exhibition making activities in Cambodia before you co-founded SA SA BASSAC?

I was always involved on a volunteer basis with local spaces including Reyum Institute of Art and Culture and Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center, both amazing institutions dedicated to cultural preservation and continuity, as well as the French Cultural Center (now French Institute) before its policies became so conservative. My questions were how and why and by whom were exhibitions being made in Cambodia? Cambodia was much more isolated politically and culturally than it is today, and in general, deviations from longstanding cultural and aesthetic codes were subject to critique. If in the role of a curator, and as a visitor, I felt I was not in a position to deviate unless I was supporting artists who wanted to. So I took a very involved yet kind of invisible role for many years as an assistant, and along the way, took note of the evolving needs of artists unmet by the existing infrastructures. At Reyum I was fortunate to assist the co-founder Ly Daravuth with fundraising, publications, and at the Reyum Art School with curricula and exchanges such as with Tran Luong. Also through Reyum I met many artists, teachers and Ministers from the older generation who were teachers and Ministers who survived the wars and were sent by the Vietnamese-ruling government in Cambodia in the 1980’s to earn masters degrees in post-soviet blocs. I had the chance to deepen those connections when I assisted Cambodian-American artists Sopheap Pich and Linda Saphan in their project Visual Arts Open – a multi-venue inter-generational exhibition program for a few weeks in December 2005. I curated the photography component of VAO, for which I invited Cambodia’s leading photojournalists to develop existing work made outside their commitments for press, alongside then-emerging photographer Vandy Rattana who exhibited his first body of work Looking In – radical in its time for its documentary yet non-newsworthy nature: an intimate, cinematographic-like portrait of everyday low-middle class domestic life. What a meaningful experience for both Rattana and I to be at Jeu de Paume this year, 10 years later. By 2008 I founded my own curatorial platform called Bassac Art Projects, a name and logo that would serve the purpose of looking like another NGO (until recently Phnom Penh reportedly had the most NGOs in the world) as a way of hiding my foreign name and also seeking validation for the curatorial role. Some activities of Bassac Art Projects included a symposium on curating in the region at Reyum, and exhibitions and documentary films at Bophana including on Svay Ken’s final work Sharing Knowledge. Bassac Art Projects also had a physical space – an informal residency program for local artists for making and meeting. Six sets of keys were made and they roamed between artists. This positive experience proved that uncensored space and non-deadline time were among the critical elements missing from the landscape.

Ngyuen Trinh Thi, Letters from Panduranga, 2015. HD Video, 36′. Co-produced by Jeu de Paume, Paris ; Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques ; CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux. Courtesy Ngyuen Trinh Thi © Ngyuen Trinh Thi, 2015.

Did you notice any changes in the Cambodian art world?

Many, many changes. I’ve heard many stories from artists from former East Germany before and after the wall came down or stories from other countries that have seen major political and economic changes such as Myanmar recently, and these resonate with the experience I’ve seen in Cambodia. Since the economy began to open in 2005-2006 and relative peace had been maintained for the better part of a decade, the regional and international ‘community’ decided to participate with Cambodia and vice versa. One notable and sad change was the death of Reyum’s co-founder Ingrid Muan and ultimately the closing of Reyum around 2009. The type of ethnographic inquiries they made through research, exhibitions and publications and programs is very missed. To name a few positive changes: the opening of spaces that accommodate a wide range of practices, the formation of Cambodian collectives like Stiev Selapak, film collective Kon Khmer Koun Khmer and the rise of the documentary and many film festivals, along with many collectives in the northwestern province of Battambang who are primarily painters; the ability to access archives related to Cambodian history through the opening of Bophana; the growth of public programs at all spaces that exhibit art, both as animator of exhibitions but also events in their own right, the increasing of regional and international relationships amongst curators and artists leading to an increase of residencies and participation for artists. While there seem to be more of everything – more artists, more exhibitions, more activity, more festivals, I’ll avoid sensationalism with the word renaissance which is being used so often in journalism about the contemporary art scene in Cambodia. While there is reason for celebration and excitement indeed, the more we learn about the past the more we can see the ‘changes’ as continuities of a past that is hard to access due to war that targeted the educated classes including artists and the destruction of archives.

Sa Sa Art Gallery was founded in 2009 by the art collective Stiev Selapak to promote Cambodian contemporary art in the context of a Cambodian artist-run commercial gallery. Can you talk about the shift from this first space to the founding of two other spaces, Sa Sa Art Projects in 2010 and SA SA BASSAC in 2011?

Each initiative has been experimental in nature. Stiev Selepak (acronym Sa Sa) came first in 2007 – a group of young photographers united in knowledge and resource sharing. Vandy Rattana instigated the group – many of them having just completed the year-long photography course with French photographer Stephane Janin who had a beautiful photography gallery for a few years in his repurposed shophouse near the fine art school. Stiev were committed to creating and providing their own image of themselves, an image that might contribute to destabilizing the ethnographic gaze by the French Protectorate, the anonymous images of war, the tourist snapshots, and to contribute to an archive of daily life for future generations that is largely missing for their own. Their practices remained individually authored yet they supported each other, and eventually opened the commercial Sa Sa Art Gallery in 2009 as a way to exercise more control over the way their work was exhibited and shared, and to support young Cambodians who wanted the same. Their program notably nurtured and increased the number of Cambodian audiences. The gallery closed around the time and partially due to the opening of Sa Sa Art Projects in the White Building. Stiev member, artist and curator Vuth Lyno was directing both spaces and working full time for the United Nations – impossible to do all. The collective decided that community-based and experimental practice should take precedence and Stiev focused on the Projects space, hosting talks, workshops and residencies and community-wide events. Meanwhile my Bassac Art Projects was collaborating with various members of Stiev and I agreed with them that the residency aspect of Sa Sa Art Projects was crucial for the art community. But then we were missing the role Sa Sa Art Gallery played. Rattana and I had been searching for a space for a small art center for many, many years and always believed it would appear at the right time. In fact our ideal space was offered to us at first right of refusal – located down the same street from White Building and tucked away near the historical Royal Palace and National Museum – circumstances that encouraged us to open SA SA BASSAC in 2011. SA SA BASSAC and Sa Sa Art Projects work parallel to one another, and we collaborate when it is natural, for example when a strong student comes from SSAP art classes, SSB will engage him in an exhibition or public program, or this weekend we are co-presenting screening program at another local venue Metahouse.

A group of students, artists and professionals participate in the workshop series Cambodian Art Histories for Daily Use, conducted by Roger Nelson at SA SA BASSAC, 2015. Courtesy SA SA BASSAC / Lim Sokchanlina.

What is SA SA BASSAC’s exhibition program?

It keeps changing based on changing needs, and we will continue this way. Both SSB and SSAP are responsive places to the local context. We are artist centered, and working at the capacity of small teams with precarious means. At SSB we’ve evolved from 12 exhibitions per year in 2011, to seven in 2015. Whereas this sounds downward, it is very much upward since it means we are now are assisting with so many exhibitions abroad, nominations, residencies, and it allows home audiences to see the works for longer periods. The first two years focused intensely on solo exhibitions by local Cambodian artists. It was all an experiment, a test if new works from a broad range of artists, backgrounds and practices would resonate and with whom, and if artists could live as artists in Cambodia today and find supportive channels in the evolving art world, near and far. Integral to the exhibitions were a wide range of public programs, and alongside this a growing library. In the third and fourth year the program opened to a number of exchanges for example with the region of Southeast Asia via guest curator Roger Nelson, to a group exhibition with US-Cambodian diaspora curated by Vuth Lyno, as well as other discursive and playful platforms, through which we are becoming more public, more of an art center. We are currently hosting The Vann Molyvann Project: Summer School 2015, led by architect and urban researcher Pen Sereypagna. The project focuses on the works of Cambodia’s most celebrated but understudied modernist architect Vann Molyvann, who is nearing 90 years old. The gallery space acts as a transparent architecture and research studio designed to engage students and visitors with processes of collaboration, research, archiving and building around Vann’s guiding principles, New Khmer Architecture, histories of urban development, and the model-making craft of the past and the technologies of architecture today. Our upcoming exhibition by Svay Sareth is sure to be provocative as it engages with questions around the historical and ongoing tensions between Vietnamese-Cambodian political relations. The exhibtion “I, Svay Sareth, am eating rubber sandals” is on view from 26 September to 28 November 2015.

(Image on top: Ngyuen Trinh Thi, Letters from Panduranga, 2015. View of the exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, Paris)

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton