Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff

Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff: “Fiction is about making sense of what we cannot control”

Phone storage space has skyrocketed. We take too many blurry photos, sporadic notes and screen shots, never looking at them again. And so we pay for more storage capacity and move on. All of these organizational methods keep us from grasping, or sensing any sort of coherence or progression; perhaps even blocking access to a buried emotion or direction which could help us find some form of meaning. It has often been said that history accelerates, making our heads spin, but perhaps it is simply our externalised memories which have too often malfunctioned.

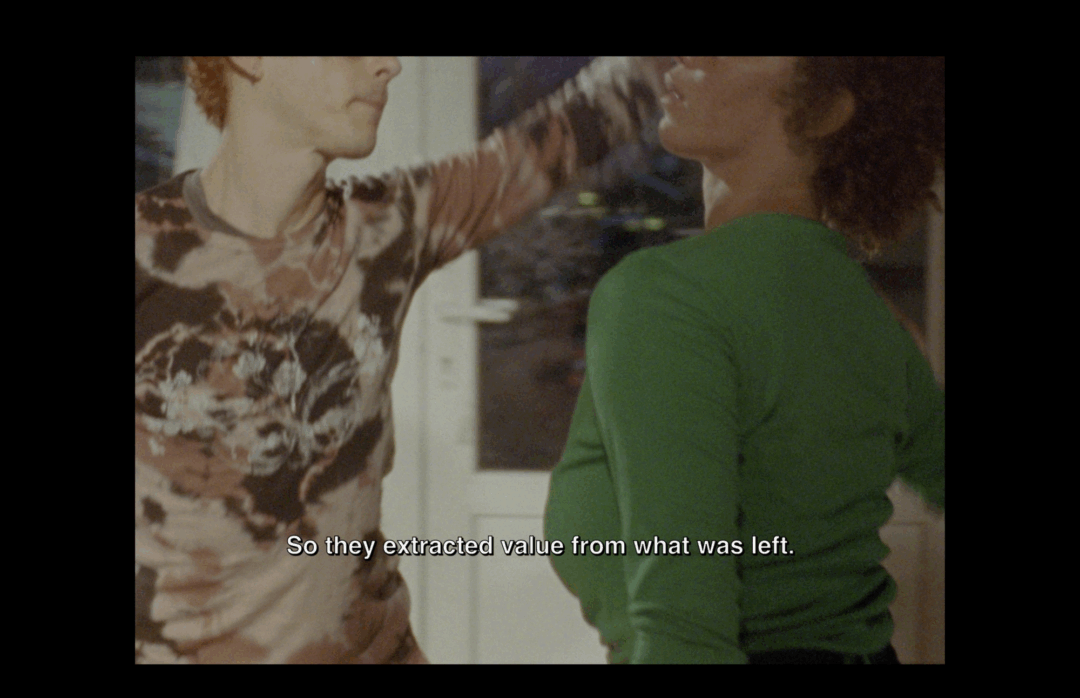

Over the past fifteen years or so, artist duo Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff have generated a personal, perspicacious and rich oeuvre; the timely themes they address include documentation, memory, the tech industry and collective practices. Together, the artists—who were born respectively in 1988 and 1987 in the United States—have founded functional places for interaction between people in their cohort, who are also at the source of narratives and pleasantries which end up as texts, plays or series. In Berlin—where the pair have been based since 2009—these structures have taken the form of the illegal Times Bar (2011-2012, co-founded by the artist Lindsay Lawson), an amateur platform for the performing arts, New Theater (2013-2015) or a second bar and studio set, TV Bar (2019-2022).

As the 20s wheezingly accumulated, the duo crossed the Atlantic again. Calla Henkel authored two successful novels: Other People’s Clothes (2021 for the French translation) and Scrap (2024), which were predominantly received as edge-of-your-seat thrillers, while a handful of readers saw possible narratives of a certain type of artistic milieu in Berlin, from behind-the scenes. Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff have been running the New Theater Hollywood in Los Angeles since 2024, while their first monograph, German Theater 2010-2022, was released earlier this year. They agreed to revisit the development and intentions of their joint practice with us. Perhaps it is also an occasion to re-evaluate our relationship to fiction, rather than facts.

Times Bar interior, 2012.

Courtesy the artists and Galerie

Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

Times Bar interior, 2012.

Courtesy the artists and Galerie

Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

You met as art students at Cooper Union in New York. What led you to study art originally? What was your practice like then and how did you decide to work as a duo?

Max Pitegoff – We began working together through photography, which has remained a common thread in our practice. We were both interested in performance, and the social aspect of performance, especially its documentation: how you capture something that isn’t just the random single image that exists after the event. We developed a practice while we were still students where we shared a camera, so it was unclear who was taking the photograph. Then, we started to develop our own performances in order to document them.

Going to Cooper Union shaped our relationship to collaboration. There were long shadows of other artist collectives and their ways of working. For example, the members of Bruce High Quality Foundation [formed in 2004] were students some five years earlier and they were having a big market moment when we were in school. So many friends were hired by their studio immediately after graduating. Ten years earlier, there had been Art Club 2000 [1992-1999]; Patterson Beckwith was one of our first photography professors. Doug Ashford, who was part of Group Material [1979-1996] with Julie Ault and Felix González-Torres, was also one of our professors. It was in the air, and it created a groundwork for us. We were being taught the language of how to work collaboratively, and simultaneously developing our own version of it.

Calla went to study abroad in Berlin. After being in the financialized New York of the mid-2000’s, Berlin presented an alternative. It was 2009, and Berlin had a utopian feeling. It was a place where people had time to experiment, time to hang out late into the night, and therefore also time to join in in these bigger social performances that we were starting to do.

Extraits du film / Film stills. Courtesy the artists, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin and Cabinet, London.

When did your collective structures, the bars, the theaters or the TV set, start to function as what you have called “narration machines”?

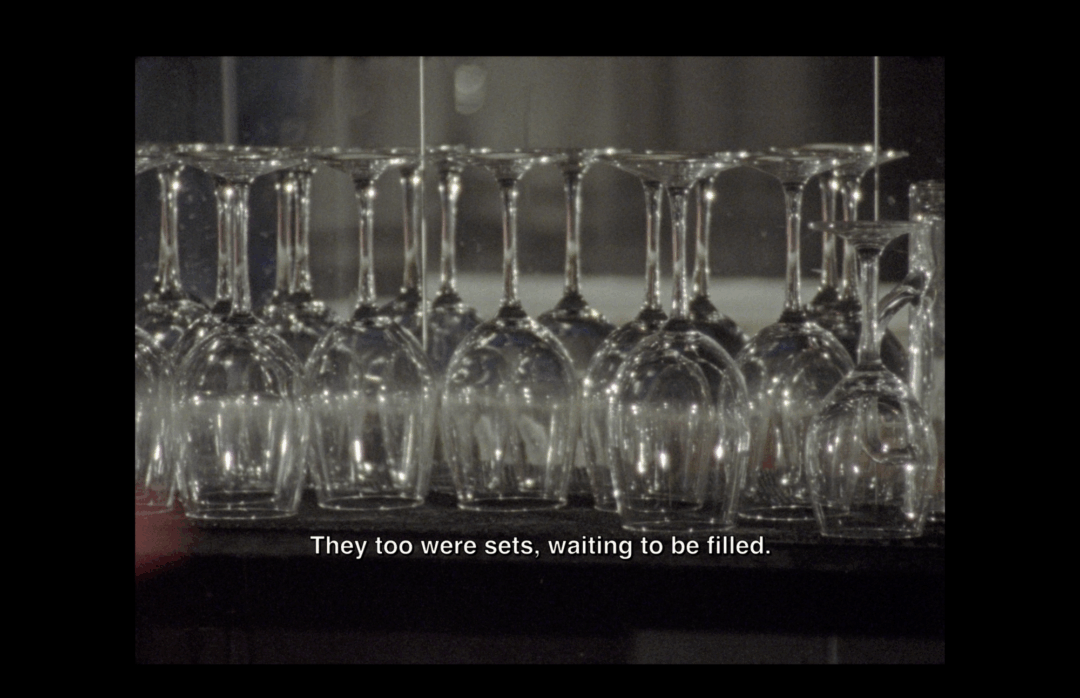

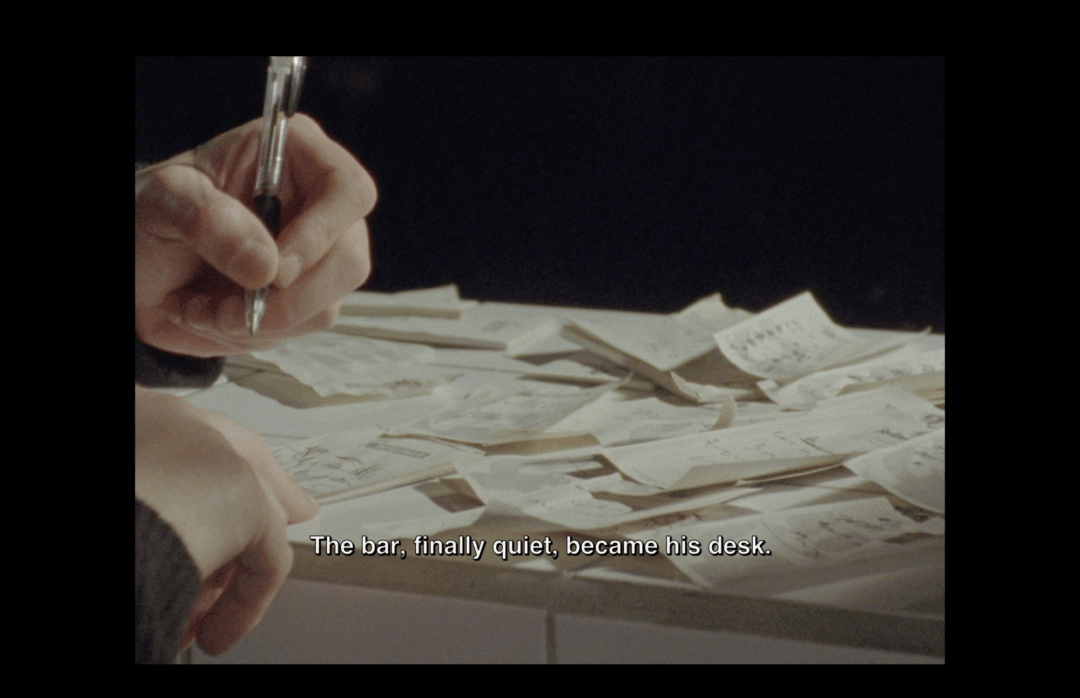

CH – We adopted the Berlin ethos of photography fairly quickly. Berlin has a gorgeous history of a “no photos” policy in clubs, which is part a form of protection towards privacy and hedonism but also has created an interesting abstraction of nightlife. So, at Times Bar, we started only photographing during the day; the remnants of what was left over, or the artworks which had been installed above the bar. Then, we slowly started writing things down in the tab book, which became more and more baroque with each month. It started out just documenting who owed us what, but then we started using it summarize the evenings, who was around, and eventually writing quotes of what they said.

We realized that the tab books had the feeling of a Kammerspiel, a form of intimate German theater play or chamber-drama. Sitcom-esque, with the same characters reappearing all trapped in this box filled with liquor. Every night was it’s own drama. The tab book set the blueprint for the scripts we would soon write; after all, the bar is an ideal stage. We bartended every night, and we knew that we were also performing. Everyone was putting on a show. The stage was constantly slipping. We took those ideas, and we applied them to opening a theater [New Theater] a year later.

MP – After the 2008 financial crisis, we were thinking a lot about shared fictions – in the financial world and beyond. We were also witnessing a certain moment at Times Bar in 2011-2012 when all of these former Städelschule students were moving from Frankfurt to Berlin and launching their careers. Lindsay [Lawson, American artist based in Berlin and co-founder of Times Bar] had just graduated from the school, so all of these recent graduates would then come there and network: a performance we watched unfold from behind the bar.

CH – Yes, there was a Post-Internet boom town moment.

Extraits du film / Film stills. Courtesy the artists, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin and Cabinet, London.

Gentrification quickly surfaces in your work. This is the case in your practice as a duo, and later in Calla’s first novel, Other People’s Clothes. How did you start to grow conscious of it and what impact did it have on the artistic scene?

CH – We have always been interested in the fact that artists are blamed for gentrification. To me, it’s an absurd placeholder for larger, often governmental political shifts that then are shifted on artists – the idea of the artist’s loft, for instance. Between the time that we opened Times Bar and then New Theater, the city had transformed very quickly. The other side of Internet art was the tech business, and so we really saw it coming. In Berlin, the tragedy was very set up; Angela Merkel wanted to transform the city into a tech haven.

MP – We had already seen it, the tail end of it, in the East Village, and our professors who owned Soho lofts that they had bought in the 1980s. So, when we saw a version of it happening in Berlin, we were sensitive to it. Times Bar was an English-speaking artists’ bar in Neukölln, an area where there were not yet so many of these types of spaces. This meant that from the start, we were asking ourselves what the actual driver of these forces were.

CH – The role of the artist in gentrification informed a lot of the work. We were interested in the systems. The tax requirements for the self-employed. The Visa processes at the Ausländerbehörde which had previously been very generous to artists but began to favor tech workers. We were really sensitive to it, and we were afraid of it, but we were also inevitably a part of it, so a lot of the work we did then centered around the question of how one can exist within that system.

What is your relation to truth and authenticity in the age of digital memory? Can fiction become a sincere document when access to facts is more and more uncertain?

CH – Because we had this relationship to documentation and performance, we learned early on that documentation is never true. It is never the thing itself, so documentation becomes its own version of fiction. We are now interested in how we control that version of fiction. We were obsessed with how, in the1980s and early 1990s, one photograph of a specific Martha Graham dance became the representation of it. That is a fiction. One of the pieces that totally changed our brains about embracing the cleaving of truth from documentation was Charles Atlas’ fictionalized documentary about the Michael Clark dance company, All Hail the New Puritan (1986). It was an aha moment.

I think performance gets turned into iconography and it also gets turned into collective memory. For us, collective memory was the most interesting, and is probably the closest to the material that we now work with. For us, it’s about deciding in real time what our version of the collective memory will be. There is of course a type of manipulation to this, but it is also just ours; it will never be truly collective. It has taken us a while to have the confidence within our practice to work with the stickiness of this question.

MP – I think sincerity is the right word. Fiction can hold so much sincerity, and this fabricated version of retelling still transmits truth.

CH – We film a lot now, documenting our current space within a narrative framework, and if something changes; for instance, the building was painted red and recently, an actor moved out of state – these snags which could create continuity rifts we now write in. We can explain these changes through fiction. We can say a rich patron paid to have the theater painted. We can say that the missing actor had finally “made it” and is shooting in Atlanta. All of this allows us to use the unpredictability of reality. We could nevercontrol what happened every night at the bar; we can’t control who buys the tickets to plays. Fiction, for us, is about making sense of what we can not control.

Extraits du film / Film stills. Courtesy the artists, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin and Cabinet, London.

Calla, would you say the same logic applies when you are writing your novels? It feels very similar in the way of choosing a vehicle to give a version of certain events.

CH – I wrote the first novel after we finished the Volksbühne [in 2018]. Max and I were so sick of theater, and we needed a pause. I went back to my parent’s house, and I started to ask myself how I actually ended up in Berlin. Max and I had had such an intense decade. I just started writing and was relieved by the selfishness of writing just for myself. After years of writing niche theater, I wanted to write something anyone could read. So, I decided on a thriller. I think, also, that the work that Max and I do deals with reality and other people with such loaded sincerity, and there is a certain heaviness to that. In our duo work, we must be really careful and considerate because we involve other people, practices and conversations. We have to be slow and deliberate. With the novels, I get to just be in my own absurdist race car and make things up.

MP – The form is also very interesting. You dig yourself into these narrative holes and then you have to find a way out. You excavate your memory to do that, in a way.

CH – Totally. In the thriller format, there needs to be an answer at the end, but in our work as artists, we never provide answers, just more questions which point us deeper towards the heart. It doesn’t make the thrillers disposable, but they are closed-off worlds. The questions that Max and I have been working on continue to change and evolve, and for me there is more rigor in that.

MP – Before Calla began writing her novel, we did an exhibition in Rotterdam at Kunstinstituut Melly (formerly known as Witte de With) [Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff: Foreword, 29.01 – 10.04.2016] that dealt with our ideas around fiction, including a text about the relationship our practice has to fiction by looking at trend-forecasting and the artist group K-HOLE. It contains a lot of the ideas that we were thinking about at the time. [This text was also printed in ZéroDeux #77, Spring 2016]

CH – With Paradise (2020-2022), the film that we shot at TV Bar, we had wanted to base it a little bit on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day (1972-1973). We wanted it to be about how the bar’s employees take over the bar from an absent boss. In the real world, Max and I also wanted to hand over the bar to our employees, but the building got sold and our lease wasn’t renewed. That dictated what the ending of our film was: in the final scenes, all these people in suits come in and take over the building. It is not like it is a story by jury or committee; it is a story enforced by the reality of trying to exist, which is what shapes so much of our work.

Head image : Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff, Hotel Moon, New Theater, Mars / March 2015.

Avec les peintures de / With paintings by Birgit Megerle, bandstand by Grayson Revoir, posters de / by Alex Turgeon, plantes de / plants by Georgia Gray, et l’escalier de / and staircase by Ellie de Verdier. Photo : Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff. Courtesy the artists and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Dena Yago, Geert Lovink : “Not a single generation stood up against Zuckerberg” , Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion, Hoël Duret, CLEARING,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Clémence Agnez

Dena Yago

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Geert Lovink : “Not a single generation stood up against Zuckerberg”

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad