Taysir Batniji

Quelques bribes arrachées au vide qui se creuse

MAC VAL, Vitry-sur-Seine, 06.06.2021-09.01.2022

Of his work, we remember the enthusiasm that his discovery at the Rencontres d’Arles in 20181 had provoked, so much so that everyone had thought it was that of a photographer. The MAC VAL, a museum of contemporary art in the French département of Val-de-Marne which celebrates the sensitive, poetic, and political art of the Franco-Palestinian artist Taysir Batniji, proves otherwise. “Quelques bribes arrachées au vide qui se creuse2“, his first retrospective museum exhibition, testifies to the diversity of a work underpinned by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The artist was born in Gaza in 1966, a few months before the Six-Day War. Neither documentary nor journalistic, his work is metaphorical. In 1993, he pursued his artistic studies in Naples, after being trained at the University of Nablus (West Bank), and before obtaining a residency at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Art (ENSA) in Bourges the following year, with a singular double status: that of a lecturer on the one hand, and that of a student in his fourth year of studies, on the other, coupled with a ten-year residence permit. Living in France, married, and a father, he obtained nationality in 2012. Until 2006, when the blockade of Gaza began, he had spent his life between France and Palestine. Since then, he can no longer travel freely to his family’s land.

At the University of Nablus, artistic education is very academic. While it focuses mainly on sculpture, Batniji’s training focused especially on painting. When, upon his arrival in France, he discovered the multiplicity of forms and media used in contemporary creation, he was disconcerted. He would need time to find his own plastic language.

Thinking the world from one’s own place: this is the starting point of the MAC VAL exhibition. It is also a very accurate definition of Taysir Batniji’s art. The assertion is undoubtedly true for anyone living in an exile that he or she did not choose. In his diary, Chez moi ailleurs3 (2000-ongoing), the artist photographs his daily life since he arrived in France. This existential testimony also constitutes a reflection on the very nature of photography and the making of images. Taysir Batniji’s works are never static. The artist struggles to finish a piece. The indefinition of his life as an individual structures his plastic creation. His work contains several recurring motifs: the gate, first, but also the key, which allows one to return home – a symbol of the possibility of return. For the Palestinians, it is what connects them to the land of origin. Sand also appears regularly in the artist’s work. It is a question of thwarting the stereotype of Orientalism. Batniji is an avid reader of Edward Said4. He inscribes his works in a permanent dialogue with the history of art, as evidenced by the references to Bernd and Hilla Becher, but also to the group Supports/Surfaces – which he discovered through Daniel Dezeuze’s exhibition at the Box, the gallery of the ENSA, in 1995 –, or to Robert Morris. His artwork revolves around reality, its representation, and its artifacts, using the twists and turns of his administrative career as a driving force. There is always this back-and-forth movement between what is and what testifies, between the objects of memory and the drawings, that which remains – just like this self-portrait, lost, save for a photograph which embodies/carries its survival. Humor runs through his work. Often cynical, it sometimes becomes lighter. Everything is a pretext; everything is a metaphor. There are many self-portraits in Taysir Batniji’s work. The artist starts from himself, creates with regard to his own body, as if he were trying to fix his undefined nationality. Many of his works are intimate and precarious: footprints, piles of suitcases, etc. He is obsessed with the relationship to territory.

The exhibition opens with an autobiographical questioning of death: a video made from a 2003 shooting in Gaza. This questioning is the starting point of the portrait: a still frame of the artist’s dark and oversized face, who focuses on not blinking every time an explosion resounds during the bombings. The video installation is accompanied by a short text transcribing the answer of an Israeli army commander to a journalist asking him about the noise of the bombs: “a background noise”. This is also the title of the work.

One might understand Taysir Batniji’s self-portraits better in the light of ID Project (1993-2020), a work that summarizes his administrative itinerary in sixteen facsimile documents, constantly bringing him back to an undefined identity. On the travel pass he received from Israel, “undefined” is written next to “nationality”. How does one go about constructing oneself in this region when Palestinian nationality is denied? In the early 1990s, after the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian Authority was briefly authorized to issue its own identity papers. It then managed a territory made up of two separate areas: Palestine and Gaza. Just like on the travel document issued by Israel, there was no mention of nationality. While the French administration did not recognize the term “Palestine” after 1948, Taysir Batniji still had to prove that he was Palestinian. After 2006, the artist would make three attempts at returning to Gaza, which would result in three failures.

Created between 2005 and 2006 in the shops of Gaza, the photographic series Fathers shows the framed portraits of the founders of the shops in their environment. The portrait of the founder is both the private altar referring to the family and the collective public memory of the trading place. The store, as a place neither totally private nor totally public, constitutes an in-between. The exchanges with the territory were complicated. When his mother died, Taysir Batniji was unable to attend her funeral, as he did not obtain permission to return to Gaza. An intimate, almost imperceptible tribute, To My Brother (2012) is a series of sixty white engravings on a white background handmade by the artist reproducing, in counter-relief, the outlines of the wedding album of his brother Mayssara, killed before his eyes by an Israeli sniper on the ninth day of the first intifada in Gaza, in 1987. Taysir Batniji was then twenty years old. Remembering death at every moment – perhaps this is how those who have experienced war go through life. The second intifada is echoed by Gaza Walls. This series of photographs taken in the streets of Gaza highlights a double disappearance: that of the martyrs’ physical body and that of their representation, erased by the – natural or voluntary – destruction of the posters with their effigy. In Watchtowers, the series of towers and watchtowers that he created in 20085, the artist decided to list, according to the same typological process as the beakers, the Israeli watchtowers that invaded the Palestinian territory. The ensemble bears witness to the violence of the very principle of colonization. In the series of drawings entitled Après coup (GH0809), he imagined what remains of the houses destroyed during Operation “Cast Lead” (2008-2009) which, for the first time, saw the use of white phosphorus shells “nibbling” the bodies. Taysir Batniji produced drawings that sometimes became objects and materialized. He was then in Gaza for the last time.

The keys first appeared as rusty prints on rolled canvas (1997), an installation influenced by the Supports/Surfaces group. Later on, the exact copies of those that appeared on his keychain in Gaza would be crystallized by the artist (2007-2014). Non-functional, extremely fragile, they were the metaphorical illustration, not only of an impossible return, but also of the daily immobilization of an entire people, powerless against the control of space and time. The keys refer to the Nakba6, the Palestinian exodus of 1948, during which seven hundred thousand people were displaced, taking their keys with them as a promise. The keys were also those of the abandoned workshop in Gaza, which the artist reproduces regularly. Wood shavings obtained using pencil sharpeners litter the floor and fill the space. They evoke the poppies – “Hannoun” in Palestinian dialect, also the title of the installation –, which are the first flowers to grow back on the battlefields. Their color is red, like blood. The pencil sharpener is a childhood memory for Batniji. It is linked to learning, to repetition, which he hated. Thus, to postpone homework time, he would sharpen his pencils until they disappeared.

Taysir Batniji’s work tells the disasters of the world from his point of view, at his scale. His studio, his suitcase, his works are all proof of his existence. Suspended Time (2006), an hourglass lying on its side, fixes time, movement, and space, by immobilizing the sand. “Nothing is permanent,” as the Arabic saying goes – a saying that the artist was careful to have engraved on hundreds of soaps piled on a palette, and the fragile hope of which appeared in the double dissolution of the work – since to the precarious, soluble material was added the dismantling: visitors were invited to leave with a piece of soap.

The MAC VAL exhibition ends with a video in which Taysir Batniji films himself in his Marseille apartment in 2003, dancing to Gloria Gaynor’s I Will Survive, in its version revised and corrected for the 1998 World Cup. The video, a superimposition of two concomitant shots, was made in reaction to the Iraq war. Humans, like plants, are endowed with the prodigious capacity to adapt to the environment in which they are displaced. Through his work, Taysir Batniji embodies a poetics of memory: that of the exiled, of those who are never quite from here, nor ever really from there. Faced with the impermanence of his identity, plastic creation appears as the expression of his existence in the world.

- Guillaume Lasserre, « Taysir Batniji. Une histoire palestinienne » (“Taysir Batniji. A Palestinian Story”– free translation), Le Club de Mediapart / Un certain regard sur la culture, 2 août 2018, https://blogs.mediapart.fr/guillaume-lasserre/blog/020818/taysir-batniji-une-histoire-palestinienne.

- “A few scraps snatched away from the deepening void” (free translation).

- “My home, elsewhere” (free translation).

- A literary theoretician, a political commentator, and a humanist, Edward Said was born in Jerusalem in 1935, in a Palestinian family. He taught English and comparative literature at Columbia University, in New York, from 1973 until his death in 2003. In 1978, he published Orientalism, considered to be the founding text of postcolonial studies. (Author’s note.)

- Taysir Batniji’s extreme difficulty in returning to Gaza led him to delegate the taking of his shots. (Author’s note.)

- “Disaster” or “catastrophe” in Arabic.

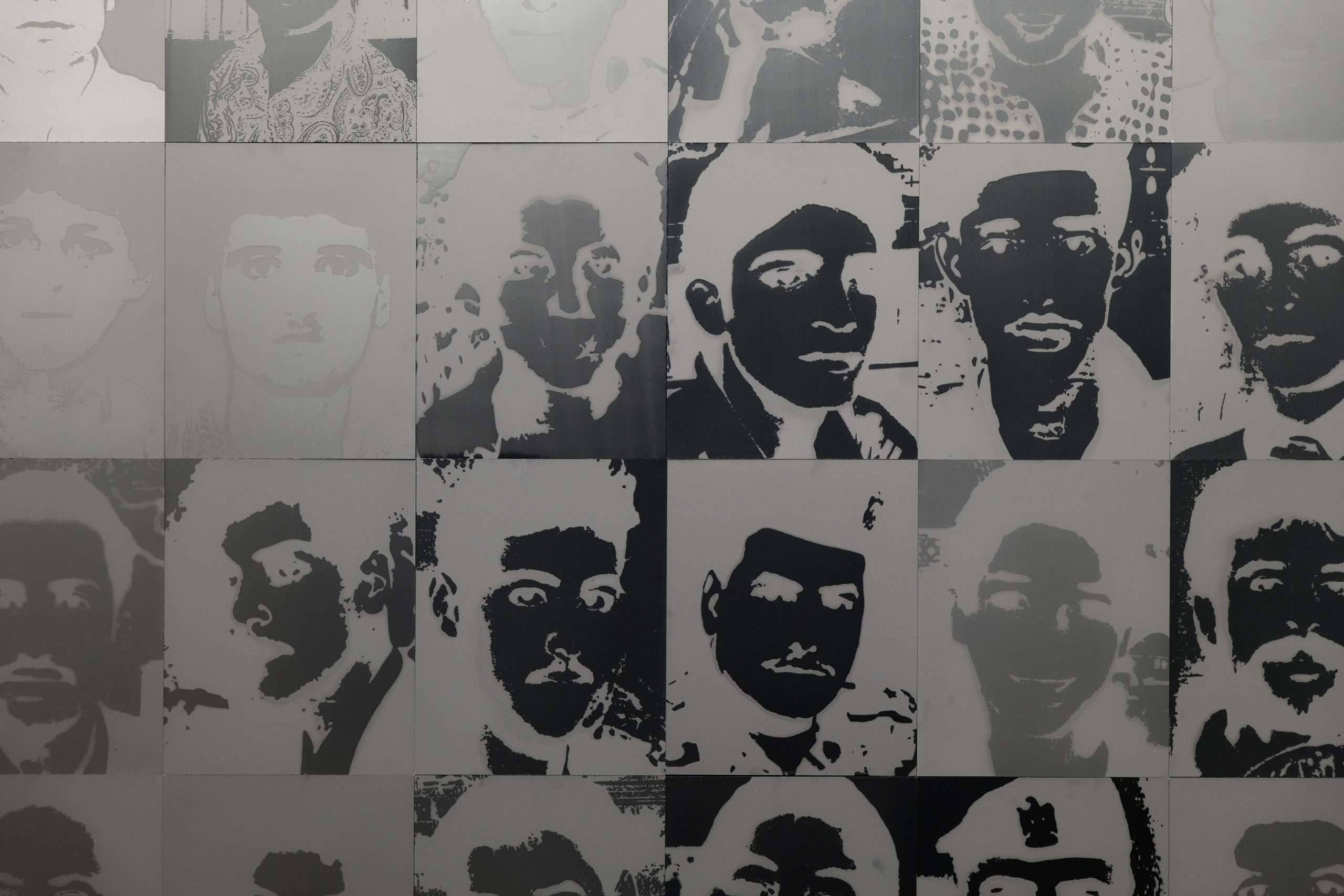

Image on top : Taysir Batniji, sans titre, 2001 – 2014. Série de 177 portraits, sérigraphie sur Dibond, 31 × 39 cm (chaque) / Series of 177 portraits, silkscreen on Dibond, 31 × 39 cm (each). Courtesy Sfeir-Semler gallery, Beirut/Hamburg. Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view « Quelques bribes arrachées au vide qui se creuse », MAC VAL 2021. Photo : Aurélien Mole © Adagp, Paris 2021.

- From the issue: 97

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Laurent Proux, Candice Breitz, Rafaela Lopez at Forum Meyrin, Banks Violette at BPS 22, Charleroi , Yoshitoro Nara at Guggenheim, Bilbao,

Related articles

Streaming from our eyes

by Gabriela Anco

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Don’t Take It Too Seriously

by Patrice Joly