Nicola L.

Nicola L. Icon, Fractured Subject, Living Artwork

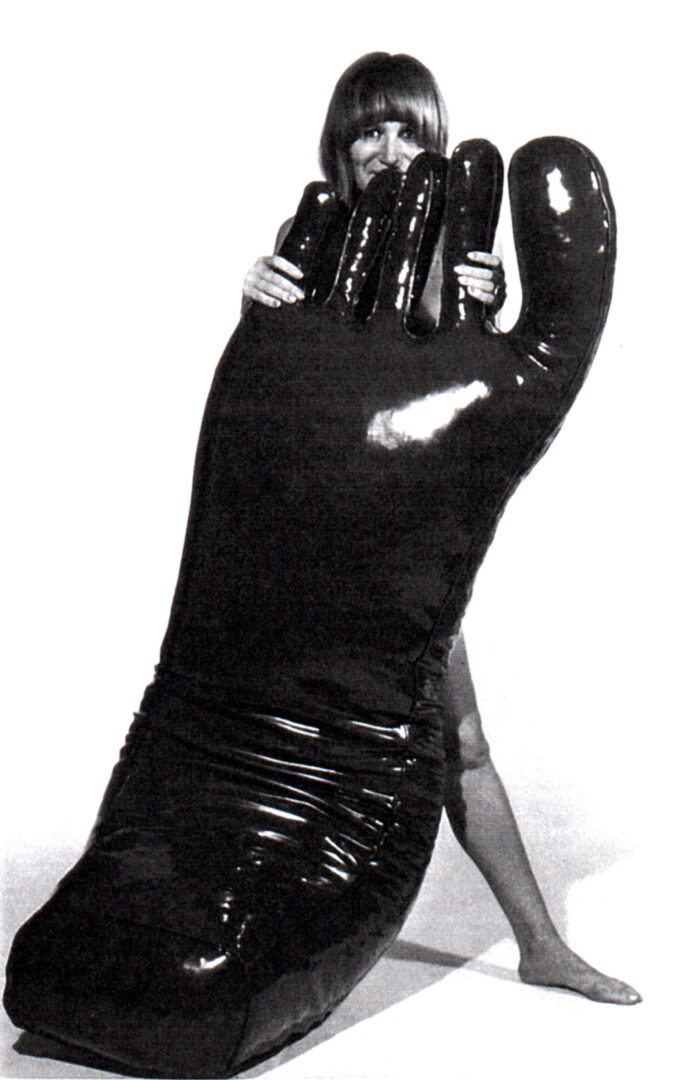

Wearing a blunt cut fringe while a vague smile plays on her lips, she dominates the frame with a semi-ironic gaze, her arms wrapped around an oversized foot, black and smooth like leather underneath the overhead lighting. The vinyl surface captures the artificial light, glinting, while bare legs form a radical contrast with the massive size of the figure. No background, just her and the object. Behind the 1960s cover girl air is Nicola L. (1932-2018), an artist, and her art is an extension of her body, a space where the everyday transforms itself into territory ripe for experimentation.

“Chelsea Girl”, an exhibition at the Frac Bretagne curated by Géraldine Gourbe, attempts to tell the story of Nicola L. By immersing the viewer in the effervescence of the Chelsea Hotel, this retrospective manages to avoid becoming static. Making palpable the dynamism of a rich transatlantic avant-garde scene, along with the continual tensions of a creative community, the show manages to go beyond a mere art historical update. By combining the artist’s works with those of other figures from the New York underground scene—Brion Gysin, Claes Oldenburg, Yoko Ono and Carolee Schneemann—this “collective solo exhibition” weaves a vivid constellation of experiences and encounters, at a time when self-discovery through the arts seemed to be a viable option, while collective utopia flirted with the boldness of consumer culture.

The squat, red-brick Chelsea Hotel, with its wrought-iron balconies and labyrinthine rooms formed a backdrop for Andy Warhol’s documentation of the “Chelsea Girls” (Nico, Mario Montez, Edie Sedgwick, etc.) and their comings and goings; this creative melting pot also played host to a plethora of icons, including artists, musicians, writers, and other passing ships. It is also the place Nicola L. chose as home base after a nomadic existence between Paris and Ibiza. Later, the artist took on the role of historian of this ever-evolving source of material as a documentarian, with her Doors Ajar at the Chelsea Hotel (2011). Rather than focus her attention on the myths and legends here, she chose to instead reveal the building’s everyday aspects, the sometimes chaotic, but always stimulating coexistence of the artists who live there.

Beyond the Chelsea’s legendary status, what we are interested in first and foremost is the artist: her work, her trajectory, the communities which shaped her. Her career was far from straightforward; it oscillated, reconfigured and adapted itself. By contrast, her artistic development revealed a through-line: the human body, both as terrain for exploration and as interactive tool. Nouveau Réalisme, Pop Art, performance and feminism; her practice was a place of encounters, where the political seeped into the domestic, where design became a subversive act, where the boundary between the object and the individual disappeared. Rather than create continuity, the idea is to linger over the tensions that informed her work.

From Functional Bodies to the Last Woman-Object

Beginning in the early 1960s, Nicola L.’s fluctuating forms took on a transdisciplinary approach which avoided categorization and called into question traditional hierarchies of the visual. Her works explored a sensual grammar which bordered on Nouveau Réalisme, hijacking the functionalist logic of design while reinventing the body as performative support. A brief stint with collage marked an essential phase of this gestational process. The discovery by Raymond Hains of the artist’s compositions—and in particular of a giant body made of parking stubs—during a studio visit led him to introduce Nicola L. to the influential art critic Pierre Restany. Far from being a mere formal sally, the artist’s deconstruction of protocols of corporeal integrity were a means to reassemble the Subject in a more permeable and experimental fashion. This type of disassembly and reterritorialization of the body places the artist’s discourse firmly within a dynamic which fuses art and design; an approach which the artist has referred to using the term, “Functional Art” (art fonctionnel).

New York revealed itself to the artist in 1966, at the paroxysm of Pop Art’s heyday, representing a fundamental shock for Nicola L. The artist was able to confront the hypervisibility of industrially-produced objects via the discovery of vinyl, which would become her signature media. This soft and malleable material would allow her to extract figuration from the dictates of the icon, in order to usher in an aesthetic which allows for manipulation and semantic slippage. Through the use of cutouts and assemblage, the artist produced a repertory of

“dismembered bodies”: a foot becomes a chaise longue, the outline of a body becomes a table, dismembered forms combine to become soft and tactile structures. A mixture of sculpture, furniture, and set décor, these objects refuse to remain still and demand to be made participatory. During the 1980s, Nicola L. repeated this strategy of subversion in a design context, by creating sculptures with use value: sofas in the shape of feet or hands, lamps-as-eyes, oversized female chests of drawers.

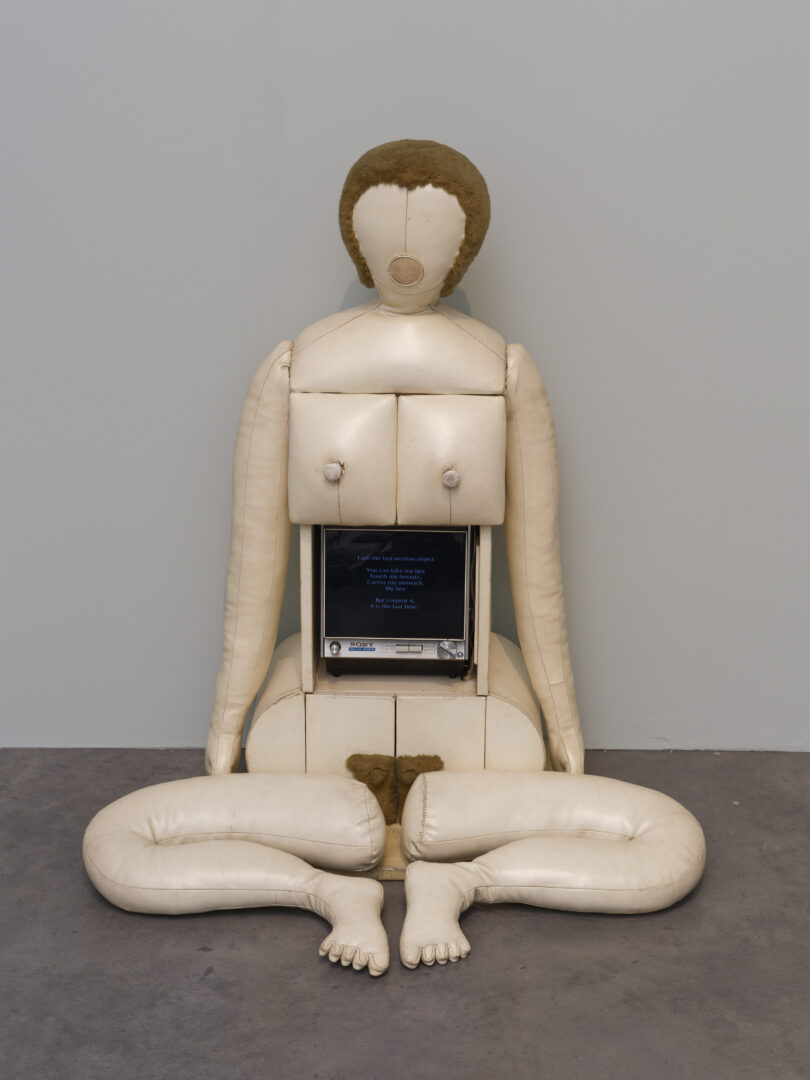

By playing up the haptics and fetichism of volume, the artist’s works become a testimony to the poetics of détournement, to formal playfulness with a dose of criticality toward the tyranny of the image and of its normative assignations. Little TV Woman: I Am the Last Woman Object is one example; an installation which combines elements from sculpture and video, it questions the reification of the female body. An encounter with Carolee Schneemann, whose raw and liberating representations of the female form challenged conventions, proved decisive and spurred the artist in this direction. In a post-May 1968 society, where the performative aspect of bodies had become a form of political insubordination, Nicola L.’s work provided a regime of self-determination where women could finally cease being observed in order to become viewers themselves. Instead of objects of enunciation, they are agents of a subversive visual language. This bodily turn, whether real or recomposed, becomes a necessary method of obtaining an openness to the world.

Frac Bretagne, Rennes. Photo : Aurélien Mole.

Flesh to be Penetrated: The Group Between Eroticism and Engagement

The first New York trip coincided with the effervescence of an incandescent counter-culture, an abundant soil where radical theatre, Happenings and political protest combined to reconfigure art and life. It was against this backdrop that the artist began collaborating with the La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. Here, Nicola L. would develop immersive stage environments which were not only backdrops but organic, living spaces as well which could be activated by the bodies of the performers. The New York experience was a decisive one: it nourished an approach in which the artwork is meant to be experienced rather than contemplated; it provides a shared process of sensorial and social metamorphosis.

Another turning point in the artist’s career was Ibiza. Spain’s Mediterranean Eden during the Franco regime was a bastion of hippie communities and an American jet set seeking new experiences—a scene immortalized in Barbet Schroeder’s film More (1969). Here, the artist was privy to a revelation one day while lying on the beach, in communion with the elements in a way which surpassed straightforward contemplation. Instead, there was the sensation of having shared the same skin with her friends. The experience proved to be fundamental, as it fed into the artist’s ambition to abolish the boundaries between the Self and others, to create spaces where individual identity could be erased in order to become one with a collective conscience.

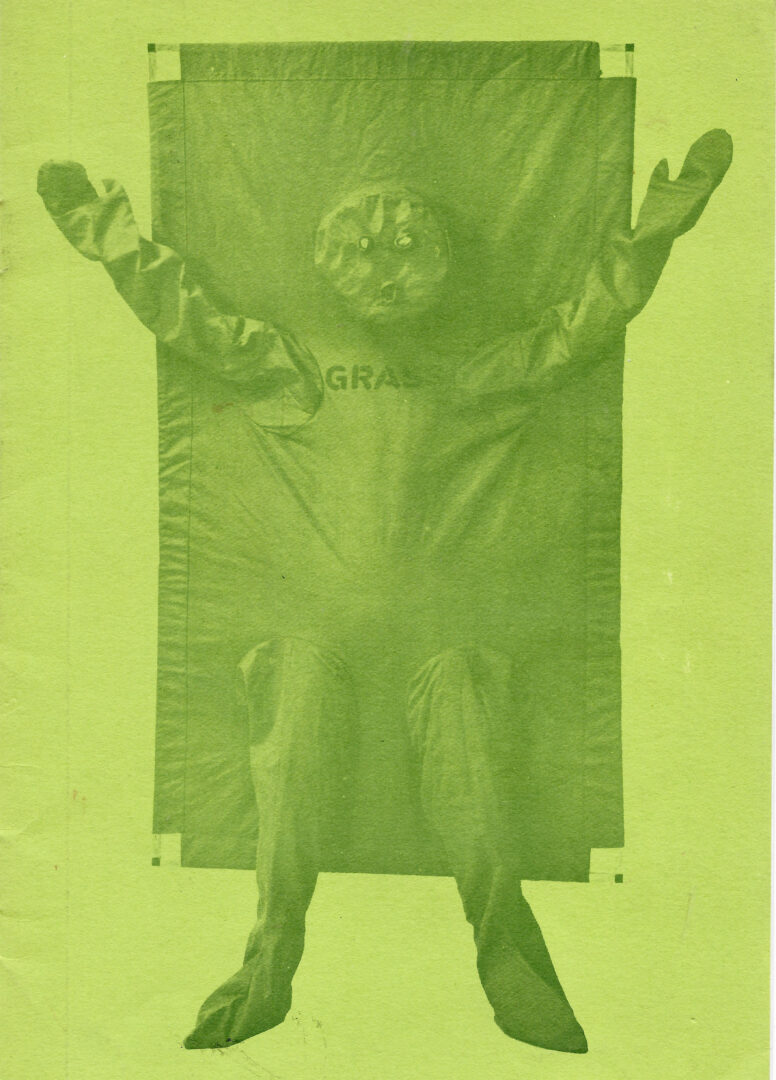

This was the context of the creation of the Penetrables, as Pierre Restany saw fit to baptize them in 1968. These strange and malleable forms did not content themselves with simply being seen, they needed to be experienced physically. Conceived as a type of second skin, they invited the viewer to slip inside them, letting themselves become enveloped in a colourful cocoon made of fabric, a space where the viewer would be required to redefine their posture. “The idea was to stop looking, and enter,” the artist stated.1

In a similar vein, the artist introduces her work into the public space, questioning the porosity between art and activism. The penetrable banners she developed in the wake of May 1968 were made to be displayed in the street, brandished during feminist and pacifist demonstrations. Inspired by the effervescence of anti-Vietnam war protest culture and the energy of psychedelic rock, the artist saw her works as spaces for confrontation and transformation. With The Bedroom in Furs (1970) (La Chambre en fourrure), which was shown in Milan at the Galleria Apollinaire, questions related to affect and behaviour induced by sensorial environments are explored. Immediately upon entering, viewers attitudes change—they touch one another, they rub against the fabric. The boundary between the private and the public becomes blurry, bodies intermingle in a sensual and political dynamic.

This dynamic reaches a crescendo with The Red Coat (1969) Le Manteau rouge, which was developed for the Ile of Wight festival. An immense collective cape, able to fit up to eleven people, is a meditation on the interdependence of bodies. “When I saw what was happening—how people were trying to get inside the coat—I had to keep going,”2 the artist explained in an interview. By inviting participants to lose themselves inside one common envelope, Nicola L. offers an experience where an article of clothing becomes a vector for transformation and the deconditioning of identity, for reinvention of social ties where the individual is confronted by their own desires as well as those of the group. Her performances, far from being mere festive Happenings, are the means for transformation: they lead toward a reckoning with others, to a feeling of tension between fusion and separation, desire and constraint. The artist’s penetrables are therefore not only interactive sculptures, they are also tools for revelation, catalysers of new types of relations.

A Portrait of Madness: The Political Transition to Video

Nicola L. began working with video beginning in 1972-1973 in Flaine, in a move which seemed to represent an immersion in another type of reality. The artist adopted this medium, which she considered a more personal, direct way of making visible the multiple lines of questioning she developed with regard to the world, to art, and to the individual. Video became a way to introduce creativity to life, a form of art which allowed one to see oneself and to understand in an instant, just like during a conversation where one hears oneself speak, and is confronted with oneself. The artist was not alone in her approach; beginning in the 1960s, portable cameras gave artists, and especially women, a unique chance to forge a new path. The first videos the artist created, where she activated her coat, could be considered an example of “cinema of the body”, as theorized by Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki—a type of film where the body becomes a site of formal experimentation and setting for political revolution.

Through experimental documentary, Nicola L. tries out the multiple facades of engagement, such as her recording of the African-American punk group Bad Brains. Each film explored a different era, while also seeking out new ways of “seeing”. In Here She Is (1975), a short film shot in Ibiza, Nicola L. sketches the portrait of an eccentric American, whose sexual desires are expressed in an open manner throughout the entirety of the film. For the artist, “madness” is, instead of a stigmatizing state, a radical expression of freedom, a way of being true to oneself. It is a profound exploration of the essence of what makes human beings so elusive, so raw, so authentic. Invisible struggles are brought to light in the works of Nicola L., giving voice to those who have so often been crushed by history.

Through her radical and visceral approach to art, Nicola L. invites us to reinvent our world view, to see through someone else’s eyes in order to undo certitudes, to welcome madness as a freeing act, as the infinite possibility to come into one’s own on one’s own terms.

1 Interview with Nicola L. by Catherine Gonnard and Élisabeth Lebovici (May 2001) and retranscribed for Femmes artistes/Artistes femmes: Paris, de 1880 à nos jours, Paris : Hazan, 2007, pp. 347-349.

2 Interview with Nicola L. by Sylvie Dupuis, Art Press, no 18, mai-juin 1975, p. 39.

Head image : Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view Nicola L. « Chelsea Girl », 30.01 – 18.05.2025, Frac Bretagne, Rennes. Photo : Aurélien Mole.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Yoan Sorin,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset