!Mediengruppe Bitnik

What the Internet can do to Art, and Vice versa, on the Face of it, anyway.

The conceptualization of time has been endlessly evolving over time. There is, indeed, a circular argument here, but it is also true that its history might easily be traced in the history of thought as well as in the history of the arts. While the time of man—intuitive, phenomenological—and the time of science—necessary, relative, and even non-existent—still co-exist, it would seem possible to say that the perception of them that prevails these days is the one that emerges from instantaneousness, whereas, in tandem, we have a perception of the world around us that is less and less direct and more and more mediated. So it is a temporal but not physical immediacy that is from now on best able to define our relation to the world. In fact, given the ten billion odd photos taken every month just by Americans—reaching the point where the idea of a Photo Free Day was even launched on 3 February last1—, several issues are now being raised: What are people really looking at? Is taking a photo to be looked at later a way of seeing better or seeing less? Are we capable of looking at the world for a whole day just with our own eyes, without the help of a captivating illuminated rectangle on which to scroll, again and again? Are we capable of enjoying our meal without sharing what it looks like with our hundreds of social friends? Are we capable of swooning in front of our little doggie-woggie’s touching gaze without instantly letting the whole planet in on the moment? Can we visit a museum without tweeting even a single selfie?

In 1994, Philippe Parreno was already wondering: “In the Mondrian show at the Museum of Modern Art, visitors desert the exhibition rooms and sit down in front of TV screens. They spend more time looking at the pictures reproduced on video than in front of the originals hanging on the wall. Why?”2 According to him, this was a way for visitors to reassure themselves because “on the face of it, people do not know how long to look at a work of art”. So it was quite practical for “the museum to manage the visitor’s time”.

The question of time in the work, of the time of the work, and of the time of art as “real” time was deliberately taken up and stated as such by artists in the 1960s, even though the matter of its representation runs through the 20th century from Muybridge’s photographic decompositions and Duchamp’s pictorial decompositions, as well as the Dada excursions of the 1920s, to Kaprow’s first happening in 1959. Andy Warhol’s Sleep in 1963, Opalka’s first Details in 1965, and On Kawara’s first Date Paintings in January 1966 just before Michel Parmentier’s first serial date stamps, then, before long, the conversations about time organized by Ian Wilson and the video experiments of Bruce Nauman and Dan Graham, all erected the time of the clock, timed and rapped out, as nothing less than the subject of the work, aimed, in the same movement, at going beyond that notion of subject, and literally inserting art into the time of man.

“Real time is not a conceptual gadget: it introduces an above all political relation, the interaction governs relations to the world, and artists are more and more aware of this,”3 wrote Parreno again. Twenty years later, and even though he died seven months ago, On Kawara is still tweeting every day: I am still alive #art.

If you were living in Zurich in 2007 and if your apartment had a land line, you might well have received strange calls which let you hear the shows being put on at that very moment in the city’s opera house. Sitting comfortably in your own home, at absolutely no charge, you could thus enjoy arias being sung by sopranos and baritones, at the top of their voices, who were passing through the city, which now houses the largest Google search centre outside the United States. Needless to add, when these events were broadcast on TV and radio, you enjoyed a better sound quality. But would you think of watching an opera on TV? With Opera Calling4, the live broadcast goes straight into your ear, in a way that is completely unexpected and, above all, thoroughly fraudulent. The fact is that this household call service is not the outcome of a cultural democratization proposed by Zurich’s city departments, but rather the work of a small group of local artists: !Mediengruppe Bitnik. With the help of bugs hidden in the Opera’s auditorium and a computer serving as an interface between the microphones and citizens’ telephone lines, they tried to share the relatively inaccessible spectacles put on in that generously subsidized cultural Mecca with as many people as possible. Those ninety-odd hours of “musical pirating” obviously gave rise to threats of court proceedings, which were in fact never taken up.

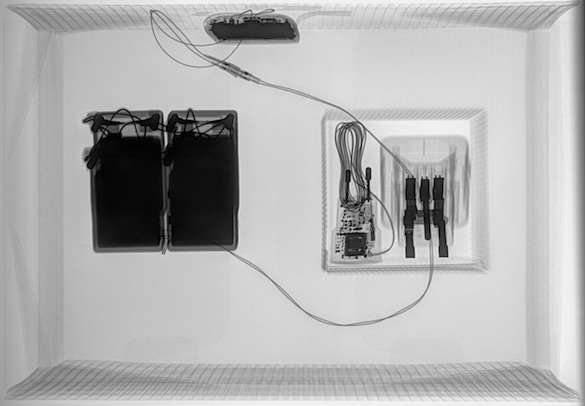

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Delivery for Mr.Assange, 2007. Inside view of the package. Courtesy : !Mediengruppe Bitnik

It is another type of “home delivery”, pizzas, which gave them the idea for the project that has earned them worldwide fame: Delivery for Mr. Assange. When Julian Assange had just taken refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, and the eyes of the media were riveted on the neat and tidy façade of the brick building, conversations were brisk on 4chan and other forums guaranteeing user anonymity. All of a sudden, someone suggested that Assange must be hungry, and it would be a good idea to order him in a pizza. A few minutes later, when scooters bearing Domino’s Pizza boxes appeared at the embassy doors watched over not only by formal diplomatic guards but also by plenty of policemen, activists, journalists and curious bystanders, Carmen Weisskopf and Domagoj Smoljo, founder members of !Mediengruppe Bitnik, were struck by something quite obvious: this was where personal history meets the abstraction of geopolitics.5 Needless to add, this collision between triviality and the height of a diplomatic crisis that was at once sensational and societal, mixing private matters with international issues, was not a first, but it called to mind the shift to what might be described as “social postmodernity”, i.e. the arrival of private life on the public stage, weighing in as never before on political affairs. The no-holds-barred publication of the Starr Report in 1998, during the Monicagate scandal, might have marked “the climax of a disastrous erosion of private life”, to borrow the words of the philosopher Thomas Nagel,6 but that affair confirmed at the same time the new omnipotence of that weapon that everybody has: privacy. If it is once again this that is rocking the albeit ferociously well-oiled machine set up by the founder of Wikileaks, it is also the breach through which back-up can arrive. The delivery of those pizzas in a zone of diplomatic immunity, ordered by people not personally known to Julian Assange, physically symbolizes the possible and almost instant interaction that the web enables any connected person to have.

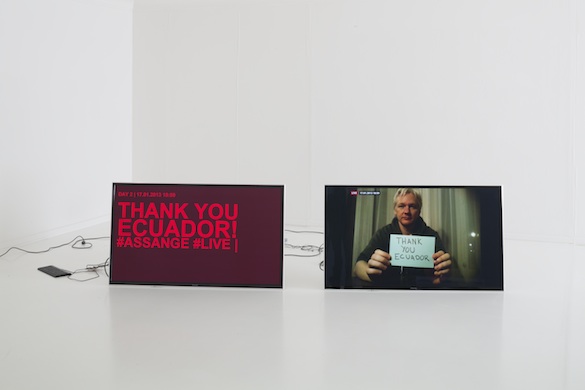

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Delivery for Mr.Assange, 2007. View of the post office from the package. Courtesy : !Mediengruppe Bitnik

Keeping tabs on an ordinary postal package can already by quite exciting—within the bounds of common sense, let us hasten to add. That renewed relation with what might have seemed beforehand to be the “postal mystery”, that time lapse between the moment when you slipped the envelope into the mailbox and that other moment when you received confirmation that it had reached its destination, today offers the anxious consumers that we all are the relative possibility of being kept informed about the whereabouts of the object dispatched. Monitoring packages has introduced into the digital network something which, it just so happens, is, on the face of it, the opposite: “material” mail. However, between the information gleaned two or three times at most during the day in question on the tracking site, and an ongoing follow-up which is presented in Delivery for Mr. Assange, there lies all the difference which gives the project its piquancy: the exploration of the postal system. In addition to the impression of being able to put yourself in the place of the package object for those few hours of its journey, the viewer/follower has access to a time-frame which seems to differ from the one in which he seems to be plunged. The video is an image-by-image assemblage punctuated by the documentary tweets which go hand-in-hand with each one of them, creating a breakup of the usual continuity of time that we are inclined to perceive. Real time, here, is at once effective and staged.

After 30 hours when not a lot happens—as far as the images are concerned—, summed up in seven and a half minutes in the video, the happy outcome brings out sharp fangs, a few words written with a felt-tip pen on blank cards, various images, and then, last of all, two hands emerging from the khaki hoodie offering silent claims, again written on the set of blank cards: Free Bradley Manning, Free Nabeel Rajab, Free Anakata… Justice for Aaron Swartz, Transparency for the State! Privacy for the rest of us!

Mediengruppe Bitnik, Delivery for Mr. Assange, 2014. Helmhaus Zurich. Courtesy : !Mediengruppe Bitnik

Who would have thought that a Twitter feed could be so addictive and, when all is said and done, so moving?

Even though the emotion stirred up by the images may not, at first glance, seem like one of the motifs of !Mediengruppe Bitnik’s work, it nevertheless also seems to be the subject of one of the key pieces in the exhibition which the small collective has jointly organized with Giovanni Carmine, director of the Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen: “The Darknet – From Memes to Onionland. An Exploration”. The piece in question, Emily’s Video (2012), is a video by Eva and Franco Mattes presented on a vertical monitor casually propped against a post in the Kunst Halle’s last room. Produced following an announcement posted on the Internet which offered anyone so wishing a chance to watch “the worst video ever seen”, Emily’s Video starts out like a classic tutorial: a series of people in front of their webcams sit down in front of the screen, saying “I’m about to watch Emily’s Video”. Some of them boast and brag while others seem a little worried, but, in no time at all, the faces they pull convey the disgust and embarrassment of these viewers, even though they are volunteers. In the end, while some laugh out loud, there are others who look away, hide their eyes, stop the film, start sobbing, and leave the room. Here the New York twosome proposes one of the most trying videos there may be, but without showing anything other than faces of people sitting in front of a camera. Here again, the effect of real time is arresting, bolstered by the fact that we know that we are watching a video which lasts roughly as long as the one watched by the protagonists who are on the other side of the screen. The viewing time for videos on YouTube or any other site hosting film is measured in suspended time, a time of absorption in the medium, in the flow of images, in the zapping which it prompts people to do, but, in many cases, the voyeurism which it introduces—via the propagation of personal videos filmed by webcam for the most part—tends to give it an appearance of “real time”.

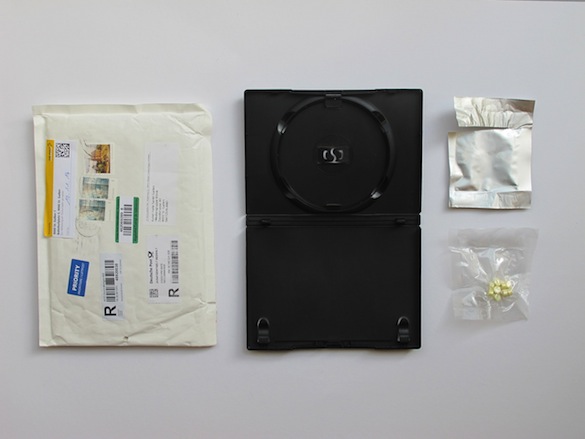

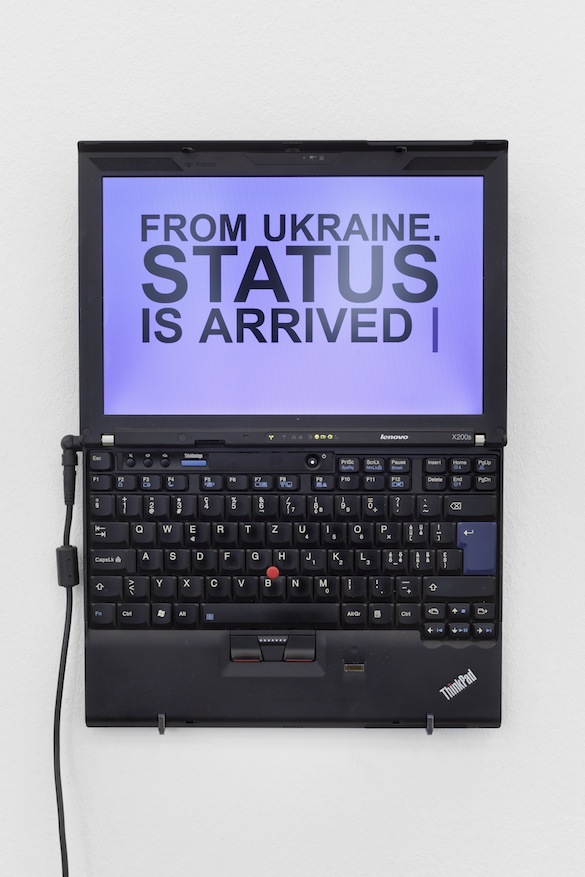

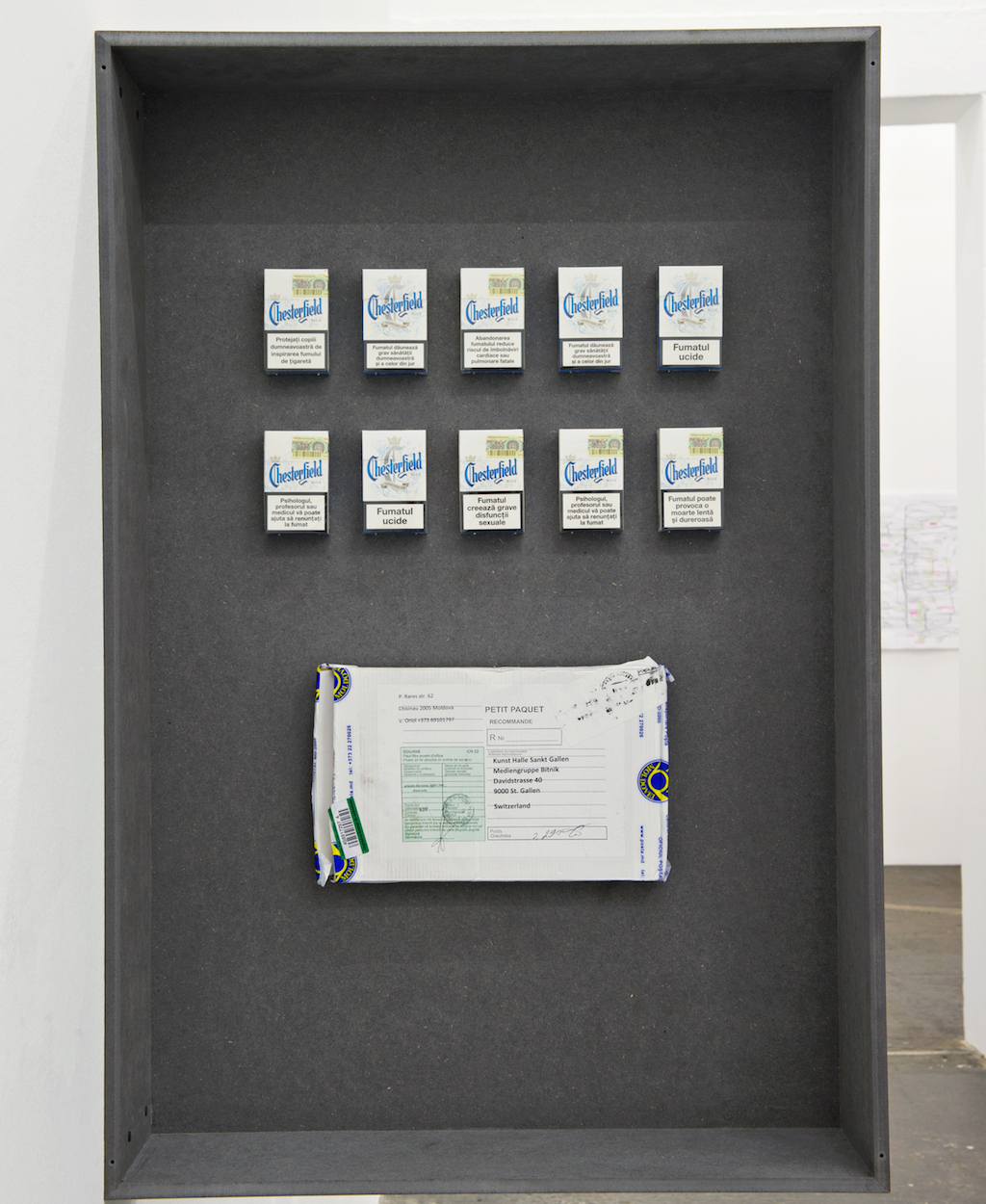

The images of the video which we shall not see and which is said to have been destroyed after the project, all came from the Darknet, that Internet double supposedly 75% larger than the network which people use every day, with its contents not indexed by search engines and on which !Mediengruppe Bitnik has submitted a computer programme, created for the occasion of the exhibition of the same name—going shopping. This Random Darknet Shopper was loaded each and every week that the exhibition lasted with a budget equivalent to $100 in bitcoins, the aim being to make haphazard purchases on Agora, a black market platform which, if we may so put it, is the equivalent of eBay on the Darknet. Its purchases were then sent straight to the Kunst Halle, and subsequently put in individual display cases. Among its acquisitions were: a scan of a Hungarian passport, an all-purpose kit belonging to London’s firemen, and some MDMA—ecstasy—hailing from Germany… This latter was not to the liking of the Swiss police, who seized the Random Darknet Shopper on 12 January last, the day after the last day of the show.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Random Darknet Shopper, 2014/2015.

The time of the exhibition became muddled here with the lifetime of the piece, which, incidentally, presented a live tracking of the shopper’s to-ings and fro-ings on a computer affixed to the wall alongside display cases which were gradually filled, but this simple relation, which was supposed to end with the exhibition, was extended beyond the time earmarked for it as a result of the legal confiscation. The time of the work that was indexed to real time is henceforth dependent on it.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Random Darknet Shopper, 2014/2015. « The Darknet », Kunst Halle St. Gallen. Photo : Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier.

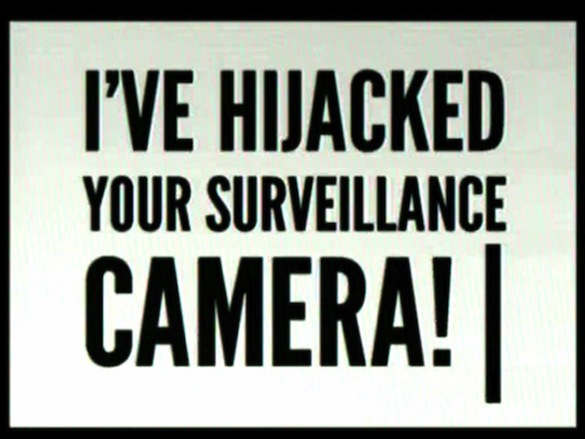

If what is involved, for the time being, is just the time of the works referred to here, we should nevertheless not cover up the juxtaposition of spaces that they produce. Be it a matter of the Internet, that space that is at once “parallel” to the physical space we live in but which, at the same time, has an influence on it and which it is accordingly harder and harder to describe as “virtual”, because of the daily interferences that it has with it, or, in a more prosaic way, of two physical spaces as distant as Zurich citizens’ apartments and the city’s opera house, or the public place under surveillance by cameras and the space of the person in charge of the surveillance, the works of !Mediengruppe Bitnik usually operate in this type of comparison: from the “drifts” that they propose in cities to the searching of surveillance cameras placed in the public place (CCTV – A Trail of Images,2008) to Militärstrasse 105 (2009), for which they capture the images of the surveillance cameras of a police station close to the exhibition venue and re-transmit them directly to it, or when, for Surveillance Chess (2012), they hack the images of a London Tube station,8 proposing a game of chess to the security guards. Unlike the other pieces, this one is, above all, intended for a single person, the agent behind the control screen. In trying to re-establish the balance between observer and observed, Surveillance Chess temporarily transforms the surveillance system into a communication tool.

Once there is juxtaposition of distinct spaces, there are connecting interstices which are very often flaws. Underscoring those which exist in the legislation9, or re-opening existing discussions, like the one about copyright with Opera Calling and Download Finished (2006), a software package for processing films which made the link between the notion of found object and films shared peer-to-peer, !Mediengruppe Bitnik particularly singles out the fact that technology is always a step or two ahead of legislation and that this step ahead, which can also be defined as a legal void, is a search time that is as fertile as it is potentially dangerous. #FreeRandomDarketShopper.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Random Darknet Shopper, 2014/2015. « The Darknet », Kunst Halle St. Gallen. Photo : Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier.

1 http://www.wnyc.org/story/challenge-2-photo-free-day/ Your instructions: See the world through your eyes, not your screen. Take absolutely no pictures today. Not of your lunch, not of your children, not of your cubicle mate, not of the beautiful sunset. No picture messages. No cat pics.

2 Philippe Parreno, “Facteur Temps” [Postman Time] (1994), in Speech Bubbles, les presses du réel, 2001, p. 19. Ditto for the following two quotations.

3 Ibid., p. 21.

4 http://www.opera-calling.com

5 Cf. !Mediengruppe Bitnik, Delivery for Mr. Assange, 2014, Echtzeit, p.15.

6 http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/philo/faculty/nagel/papers/exposure.html

7 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlZTghhCuxg

8 The United Kingdom was the first country in the world to introduce general tele-monitoring in the wake of IRA attacks. It is still the most tele-monitored European country, London being renowned as the city where video surveillance (public and private alike) is the most widespread. (wikipedia).

9 It is interesting to note that media coverage of !Mediengruppe Bitnik occurs mainly in the news press and less in the art press, as if their work was above all regarded as news, like any other news item.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Surveillance Chess, 2012. Courtesy: !Mediengruppe Bitnik

“The Darknet – From Memes to Onionland. An Exploration”, Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, 18.10.2014 – 11.01.2015. With: !Mediengruppe Bitnik, Anonymous, Cory Arcangel, Aram Bartholl, Heath Bunting, Simon Denny, Eva and Franco Mattes , Seth Price, Robert Sakrowski, Hito Steyerl, Valentina Tanni.

- From the issue: 73

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Kate Crawford | Trevor Paglen, Thomas Bellinck, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, Giorgio Griffa, Hedwig Houben,

Related articles

Céleste Richard Zimmermann

by Philippe Szechter

Julien Creuzet

by Andréanne Béguin

Anne Le Troter

by Camille Velluet