Laurent Proux

For a long time, Laurent Proux only painted industrial machines and workspaces, in particular factory interiors, which are metaphors for a rationalised contemporary world, a constant in his artistic production since his beginnings. The artist is tackling an iconographic field that has been so neglected by the pictorial domain today that it seems almost unheard of, exotic at least, the subject not appearing noble enough, therefore not dignified enough to be represented in painting. For the artist, art, craftsmanship and labour are linked by the intelligence of the hand and the precision of the gesture. ‘The worlds of work are rarely looked at for their aesthetic dimension, which is where painting comes in to sublimate grace and skill, and the idea was to pay tribute to them1,‘ explains Laurent Proux, for whom painting and industry are two fields in which “making” is involved, that of the painter and that of the machine ’taken in a human becoming2“. Factories, but also taxiphones3, call centres, African retouching studios: the aim is not to document, at least not solely, the worlds represented, but rather to divert them for exclusively pictorial purposes. For a long time, Laurent Proux painted spaces of activity and services in which the human body was absent. Now, the workstations are no longer vacant. When he started, a few years ago, to paint the living, the representation of workplaces became populated with bodies in situations, with the bodies of labourers, of workers. Because it is here, in the representation of empty workspaces, that bodies first appear.

Photo : Maru Serrano. Courtesy Semiose, Paris.

The series of nine paintings of a car production line, produced in 2014, allows us to understand Laurent Proux’s appetite for machines and the place of the factory as a favourite location in his work. It is particularly important to Proux because the automotive subcontracting plant that he uses as a model, which manufactures weatherstripping for car doors, was set up by his father. ‘For me, this series has a conclusive dimension, it closes and reopens onto something else4’, he explains. The artist’s father worked in glassworks near Rive-de-Gier in the 1960s, then as a vacuum cleaner salesman, before being employed in an adhesives company in the 1980s. He then went into business for himself, using his expertise in adhesives. The company was thus part of his family environment. Having access to an industrial site seemed natural to him at the time. This helps us to understand his almost instinctive attraction to machines. Proux would later discover that access to factories is not so easy, and his recent research and creation residency5 in Saint-Claude, in the Jura, confirmed this observation. His most recent paintings, most of which were produced during his time in residence, when the artist went out to meet workers, employees and artisans, before being completed in his studio in Montrouge, in the Paris suburbs, fully incorporate the human dimension. In this small town in the Jura with a long tradition of workers’ cooperatives, such as the Fraternelle based at the Maison du Peuple in Saint-Claude, the painter’s work is nourished by observation and engaged exchanges in the area. Back in the studio, steeped in his memories and photographs, he paints an implicit portrait of the town, marked by its industrial and social identity. The starting points for the paintings are ordinary photographs taken by the artist, documentary images from which he composes, adjusting or replacing, in order to obtain the desired effect. The origin of the use of the photographic medium can be found in the education that Proux received. The artist studied under Yves Bélorgey at the Fine Arts School in Lyon, who for many years has been creating paintings based on the representation of post-war functionalist architecture, constructed from the perspective of photography. ‘I considered that the factory is a too complex space, too saturated with information, to make a drawing from memory6’, explains Proux. ‘Each element of the photograph had to be replayed, “reacted” in paint based on a pictorial equivalent’. The painting creates a different temporality in relation to the speed of the gesture executed by the worker, which it seems to suspend.

This arrival of the bodies marks a turning point in Laurent Proux’s practice and is coupled with another, very distinct representation: intimate scenes, disarticulation of carnal, conflicting, metamorphosed bodies, bodies at once lascivious and exhausted moving through natural and sunny landscapes, freed from all the constraints inherent in society, from all established order, naked bodies forming a hedonistic ode proposed as the counterparts of those anchored in working-class reality. Two opposing aspirations which, like positive and negative, day and night, seem diametrically opposed, but which nevertheless appear to be two sides of the same coin, incompatible and inseparable at the same time. Laurent Proux thus remains faithful to a dialectical conception of painting. The attention to detail in the machines, spaces and portraits – the latter being a new feature in the painter’s work – places the working body in a certain realist tradition inherited from Courbet. Like Courbet, Laurent Proux chooses large formats traditionally reserved, in the history of art, for history paintings. Like him, he will transgress this historical hierarchy and use it to pay tribute, by magnifying them, to those who, workers, peasants, employees, simple anonymous people, are not destined for pictorial posterity. From the Madonna with Tool to the Builders, the recent corpus produced in Saint-Claude is, in this respect, emblematic. The painting Archery. ESAT. Saint-Claude, Haut-Jura (2024) illustrates another category of people who are invisible and very rarely represented. “During the visit to the ESAT, I attended an archery lesson: one person began to mime the movement, and the person they were talking to copied it with their hands. Suddenly, a particularly graphic exchange took shape before my eyes. ‘I asked them to re-enact the scene for a photo, then I made a small sketch as we left the tour, convinced that I had captured the central scene of the painting7,” explains Laurent Proux.

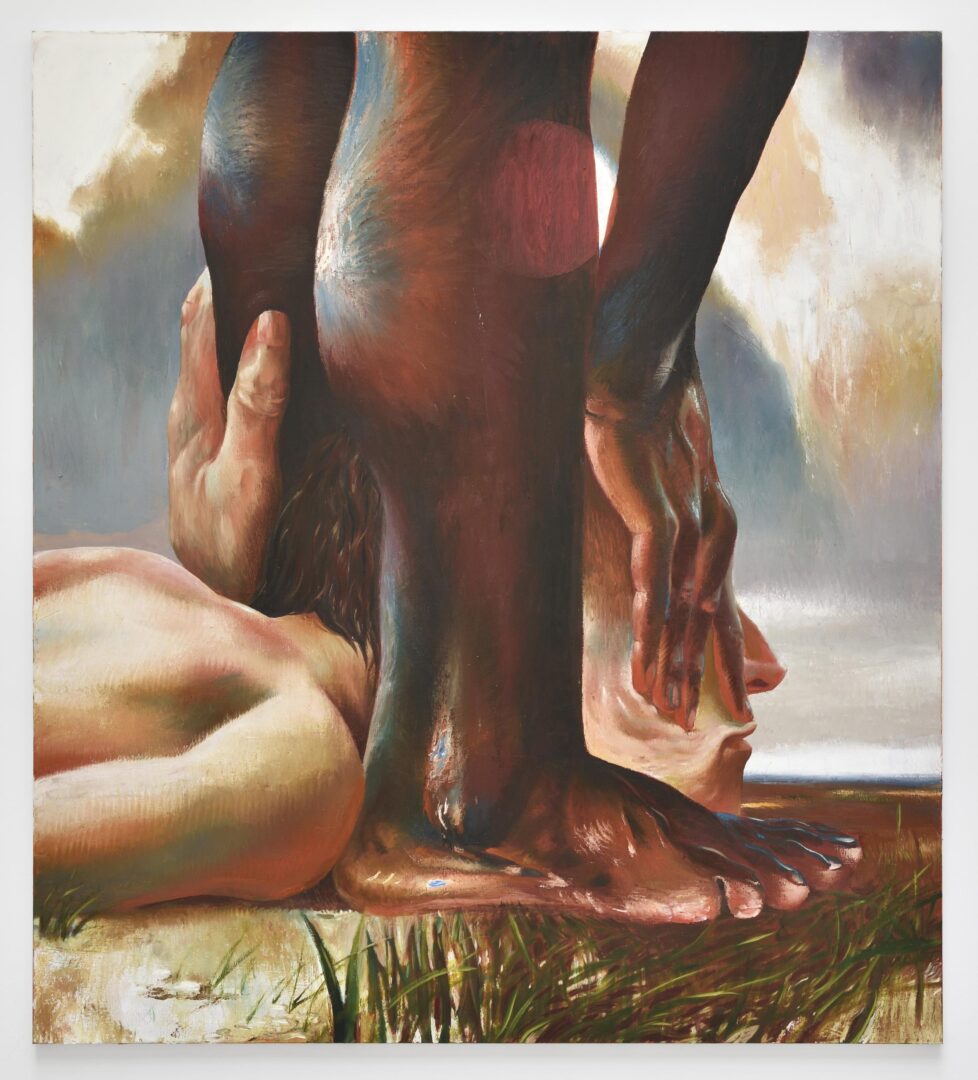

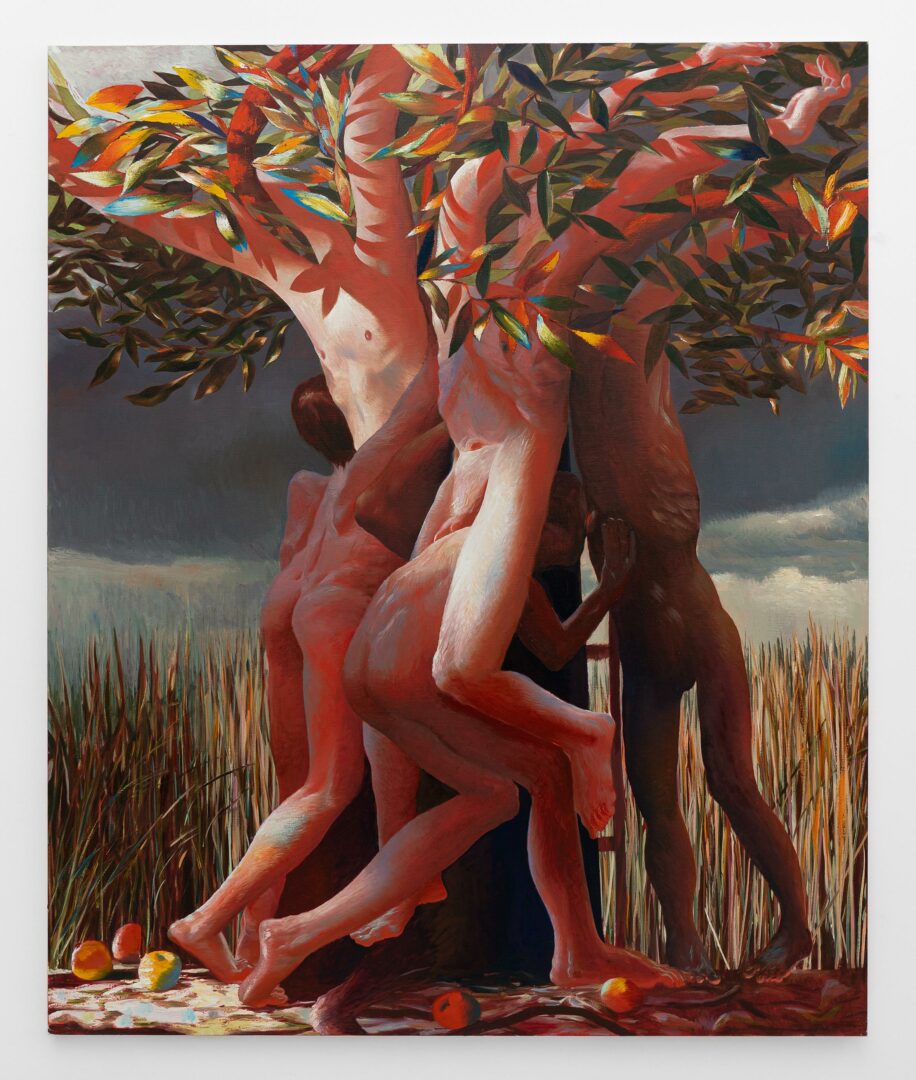

The hedonistic body is treated in fragments, exaggerations and stylisations, in order to bring it closer to a body-machine, politicised and constrained, often disturbing, sometimes sentimental, and always allegorical. Naked, tortuous, incomplete, impossible, sacrificed bodies, simple silhouettes set in artificial and flamboyant landscapes, represented in their potential for transformation and transcendence, as evidenced by the recent pictorial ensemble produced while he was a resident at the Casa de Velázquez in Madrid in 2022-2023. An allegory of bodies transforming into trees under a threatening sky, the painting Under the Tree II (Harvest) (2023) is representative of the metamorphoses and hybridisations between humans and plants, of these collective embraces of sweaty bodies whose arms become branches, whose torsos merge into a trunk. These hybrid beings, some of whom are violently illuminated while others are cast into the shadows, become one with the landscape. Other paintings are stranger, like Under the Tree. The Dormancy (2024), which takes on the appearance of a human tree; some are more disturbing, even threatening, like The Storm (2023) which shows a face in profile in close-up. He is held down on the ground, framed by the securely anchored pair of legs of a dark-skinned figure whose right hand rests on the face of the man on the ground, as if to close his eyes, without us really knowing whether it is a gesture of care or, on the contrary, a pressure, a killing. This ambiguity creates unease, making the painting difficult to look at.

Although some describe Laurent Proux’s work as realist, it moves away from this in favour of a permanent search for pictorial solutions including aberrations, collisions of planes and improbable artificial colours. The question of landscape is also present in the large factory paintings, in the very representation of the body. The artist creates openings in the closed space of the studio, like the landscape depicted between the legs of the protagonist of the painting Les Constructeurs. La Pessière. La Pesse, Haut-Jura (2024). Light becomes an operator of vision. It is the materials and the situation that make the painting. ‘What I was unable to do some time ago was to make the factory appear as a more human space than nature. I wouldn’t have been able to do it a few years ago. For me, factories were still a place of violence; reality is much more fragile and nuanced than that8’, says Laurent Proux. This machine is undoubtedly ‘caught up in a human future9’, as Julien Dunoyer puts it.

1 Laurent Proux during a press visit on 6 February, ahead of the opening of the exhibition ‘L’Arbre et la Machine’ (The Tree and the Machine), Musée de l’Abbaye, Saint-Claude, 8 February-28 September 2025.

2 Julien Dunoyer, ‘Paresses des machines’, n.d., https://www.laurentproux.com/Textes/Julien_Dunoyer_-_Paresse_des_machines

3 In the early 2010s, the artist became interested in the tension between abstraction and figuration. In the taxiphone series, cramped, ordinary spaces frequented mainly by homesick immigrants and consisting of a series of booths offering the smallest possible area of privacy, some of them are attached, through the depiction of windows, to provoke plays on transparency and opacity, maintaining this tension at work between figuration and abstraction.

4 Laurent Proux and Renaud Bézy, ‘Peindre les corps et les décors du travail. Grand entretien de Laurent Proux’, Images du travail, travail des images, no. 15, July 2023. [Online: http://journals.openedition.org/itti/4246]

5 It is currently the subject of a solo exhibition: Laurent Proux, ‘L’Arbre et la Machine’, Musée de l’Abbaye, Saint-Claude, 8 February-28 September 2025.

6 Laurent Proux and Renaud Bézy, op. cit.

7 Quote taken from the visitor booklet for the ‘L’Arbre et la Machine’ exhibition.

8 Laurent Proux and Valérie Pugin, ‘L’exubérance est beauté. Conversation entre Laurent Proux et Valérie Pugin’, in Laurent Proux. L’Arbre et la Machine, catalogue of the exhibition of the same name, Musée de l’Abbaye, Saint-Claude, 8 February-28 September 2025, Musée de l’Abbaye/Semiose, Saint-Claude/Paris, 2025, p. 21.

9 Julien Dunoyer, op. cit.

Head image : Laurent Proux, Bleu. Jeantet Élastomères. Saint-Claude, Haut-Jura, 2024. Huile sur toile / Oil on canvas. Photo : Aurélien Mole. Courtesy Semiose, Paris.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Biennale Son, Walter Swennen, Josèfa Ntjam, Michel François , Adrien Vescovi,

Related articles

Lucas Arruda

by Vanessa Morisset

Biennale Son

by Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

by Vanessa Morisset