Iván Argote

Iván Argote – Antipodos

With his installation on the column in the ‘Place Louis-XVI’, Iván Argote takes on one of the most iconic monuments in the city of the Dukes of Brittany, but also one of the most controversial, as it is dedicated to the last king of France before the royal line died out following the storming of the Bastille and the temporary disappearance of the monarchy in France. Statues dedicated to this monarch in public places are quite rare in France, and it is easy to understand why. The one that stands on its column in the middle of a square that the people of Nantes usually refer to by the name of the decapitated sovereign is located in the grandiose perspective of the Cours Saint-André and Saint-Pierre, which reflect the city’s rich architectural past. Invited by the Voyage à Nantes to create a work as part of the pedestrianisation of Rue Joffre, which leads to the famous square, the artist was naturally interested in the sculptural ensemble, producing a work that is as deconstructive as it is joyful.

While tampering with the city’s monuments is customary for Voyage à Nantes – the fountain in Place Royale, Square Cambronne, the Graslin Theatre, etc. are regularly the subject of more or less spectacular investigations by artists – we remember Stéphane Thidet’s waterfall on the steps of the Théâtre Graslin and Ugo Schiavi’s boat on the Place Royale; the Place Maréchal-Foch (the square’s real name) and its column have never been taken over by the VAN. The Colombian artist’s work is familiar with this kind of positioning, which targets symbols of power, whose foundations he revisits with great pleasure; these are monumental postures that are called into question by changes in society, but which successive local councillors find very difficult to revisit: thus the statue of Louis XVI appears as a monument that, to say the least, raises questions in a democratic society that gives proportionally much less space to its republican heroes. In defence of the elected officials, these monuments are a testimony to a bygone era that should not be forgotten and, above all, they are part of architectural ensembles that harmoniously highlight the elegance of cities. It should also be added that most of the people of Nantes (young people and new arrivals) are completely unaware of the origins of this building, with the vast majority not knowing that it was erected in 1788 in homage to the ‘benevolent king’. It therefore seems perfectly logical that the artist, the son of a trade unionist who grew up in a society that was unequal to say the least, should have taken an interest in such a monument, given that he has often targeted symbols of power in the past, particularly those that pay tribute to figures historically linked to colonialism: such as this video in which the statue of Marschal Gallieni, renowned for his abuses against the populations of the former colonies, is lifted from its pedestal and carried through the air (Au revoir Joseph Gallieni, 2021), or the bronze statue of Christopher Columbus in Barcelona, which he climbed at night before dousing it with absinthe and setting it on fire. In a different vein, but still in the same spirit of highlighting persistent tolerance of colonialism, the former resident of the Villa Medici has repeatedly denounced the presence within the walls of the famous Roman institution of tapestries that clearly display imagery degrading to enslaved peoples, even though they depict a wealthy black merchant carried by two slaves. For the artist, it is not necessarily a question of making this tapestry invisible or destroying it, which could fuel the discourse aimed at minimising the role of Europeans in the slave trade, but rather of finding another place to display it, more appropriate than an institution that is supposed to take emerging sensitivities into account. (1)

Photo : Philippe Piron / LVAN. © Iván Argote / ADAGP, Paris, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

A counter current way

While Argote tends to attack symbols of power that generally manifest themselves through an authoritarian presence in the most emblematic sites of cities, he has, in contrast, given unprecedented visibility to a ‘being’ that is considered unworthy of attention or even subject to absolute rejection: the pigeon. The monumental sculpture he erected on New York’s High Line (Dinosaur, 2024) reflects this reversal of perspectives and the importance given to a bird that is regularly vilified. This installation in one of New York’s most popular locations reveals an unexpected side to the artist, who in doing so highlights one of the most significant unspoken issues in our society: the place of animals and the attention we pay to them based on their aesthetic qualities. In passing, he also questions our relationship with these animals, which we have long considered to be our allies — using them as messengers during the First World War, before technology rendered their services obsolete — and which we now consider to be ‘pests’ or ‘useless’, which we sometimes even eliminate outright when they ‘invade’ our roofs and buildings. The title of this installation reminds us that birds were dinosaurs before they mutated and disappeared, and that it is quite possible that they will outlive us. A nod to the possible ‘dinosaurisation’ of the human species, which these dystopian times inevitably throw back at us like an existential boomerang, a monumental vanity beneath the metal plumage of this unloved creature…

Sculpture : Aluminium, armature en acier galvanisé, peinture automobile, vernis transparent aérospatial / Aluminum, galvanised steel armature, automotor painting, aerospace clear coat, 487 × 243 × 304 cm | 191 3/4 × 95 11/16 × 119 11/16 pouces / inches. Socle / Plinth : Revêtement en béton sur structure en acier / Concrete cladding on steel structure, 152 × 292 × 292 cm | 59 13/16 × 114 15/16 × 114 15/16 pouces / inches. Photo : Timothy Schenck 2024. © Iván Argote / ADAGP, Paris, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Amazement around the corner

The monumental installations of the Voyage à Nantes raise questions about our relationship with the city: do they fill a void of poetry and lightness when the ‘concrete’ rigidity of hastily constructed new buildings clashes with our thirst for curves and sensuality, poetry and alternatives to so-called urban rationality? Unlike the permanent commissions that mark the Loire estuary and were built as part of the biennial event of the same name (Estuaire Nantes<>Saint-Nazaire, 2007, 2009 and 2012), the works of Voyage à Nantes are installed for the summer season and are mainly located in the city centre, where they occupy iconic sites and monuments. These structures can be described as ‘temporary public commissions’, a kind of urban oxymoron erected for the duration of a contemporary art event before making way for new creations. These temporary projects do not fulfil the same function as ‘real’ public commissions, which require a more solid foundation and a more complex selection and decision-making process, where ‘artists are invited to participate alongside urban planners, architects, landscape architects and designers in the design and creation of public spaces and facilities. These interventions are intended to contribute to the redevelopment of urban spaces and to the aesthetic and functional improvement of living environments by giving them a new configuration (2).’ Here, the aim is more to temporarily install an open-air sculpture park for the city’s residents, but above all for a passing public, tourists attracted by the spectacular nature of these proposals. Most of the time, these invitations allow artists to engage with a different scale than that of the white cube or the museum, and respond to more playful concerns than those we are used to in contemporary art exhibitions, where humour is rarely called for: they therefore raise the question of the functionality of art, which, for some, should obey much less frivolous concerns (3). The fact is that these works must absolutely surprise, amaze or at least astonish. We expect them to make headlines by installing unusual forms that disrupt our habits and our reading of a city, and in doing so overturn narratives that we imagined to be immutable: one of the most remarkable aspects of Voyage à Nantes and Estuaire is that, in the space of a few decades, they have revolutionised the image of a city that, until then, was considered rather sleepy, where not much happened (if we forget the totemic figures such as Jacques Demy and the trade union struggles that have marked the city’s recent history and other notable events…), into a dynamic city where ‘art springs up on every street corner’ (4). We will not analyse here the relevance of such considerations, which seem to have spread throughout the country and even beyond, since contemporary art and its major biennial or annual events have long been an integral part of strategies to attract visitors and, quite simply, to promote the economic development of cities (5). In this context, fraught with constraints and pitfalls, maintaining perfect integrity and not succumbing to the siren call of sensationalism is often a challenge. Iván Argote has already had his brush with these major international events, where he seems to respond each time to the demand for monumentality while retaining a strong poetic dimension, coupled with a definite ability to create unusual situations: at the last Lyon Biennale, for example, he installed an oversized swing that required a good fifteen people to set it in motion (The others, me and the others, 2023). A joyfully absurd proposition, which made it almost impossible for the swing to function, given that its whole point is to create a movement that is both fast and light. In Nantes, Antipodos has a good chance of bringing about a real revolution in the way we perceive a square and its statuary, which until recently tended to be viewed with only a passing glance.

Acier, bois, système d’amortissement / Steel, wood, amortisation system, 160 × 1500 × 300 cm | 63 × 590 9/16 × 118 1/8 pouces / inches, 1800.00 kg. © Iván Argote / ADAGP, Paris, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

When ancient mythology meets contemporary conspiracy theories

The Antipodos belong to Greek mythology, where they are an example of the imaginary extrapolation necessary to conceive of a flat disc-shaped earth, as science at the time envisaged it; bearing in mind that in ancient Greece, science, philosophy and mythology were never very far apart. To answer this enigma of flatness, the ancient Greeks imagined that a humanity symmetrical to ours populated its hidden side: impossible to detect or know, they then thought up characters with upturned feet and a decidedly grotesque appearance, corresponding to the strangeness of such a situation. It is easy to imagine that such a legend would have enchanted an artist who works mainly in the realm of the absurd and the subversion of narratives. One can also imagine that he took a certain pleasure in joining one of the most hotly debated theories on the internet, which regularly asserts the flatness of our planet with numerous ‘scientific’ demonstrations. Flat-earthers will rejoice in having an additional ally in their quest for legitimacy and will be able to put a face to this tribe whose appearance remains unknown.

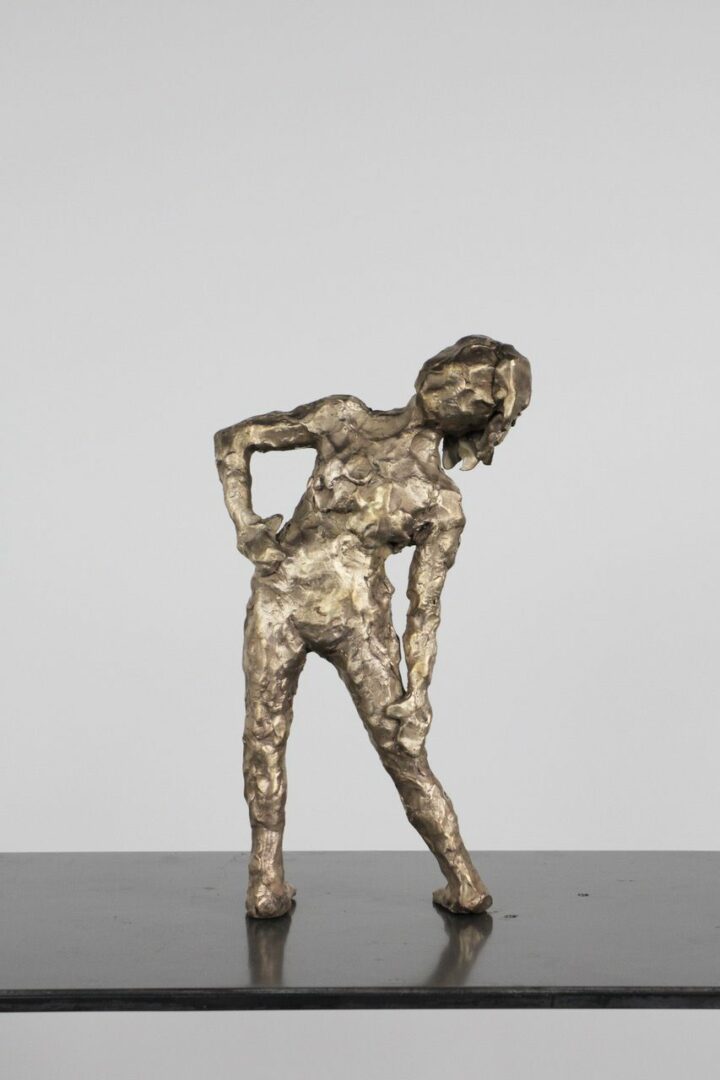

Returning to the Nantes trip, we must turn to other, perhaps less far-fetched considerations to analyse the artist’s work. By placing mirrors around the statue of Louis XVI, Argote literally makes this anachronistic effigy disappear in a gesture worthy of a cabaret magician, replacing it with the figure of a grotesque, transformist king leaving his pedestal. But this work is also a tribute to difference, embodied in a series of sculptures in which the artist has depicted these inhabitants of ‘other worlds’ — who could easily be associated with populations from distant and problematic lands or displaying real differences (in customs, gender, habits, etc.) — in postures that restore their true dignity.

This work confirms the approach of an artist who regularly attacks symbols, even residual ones, of authority and domination, replacing them with their opposites, those who suffer domination and segregation. These references are always indirect, never direct, and always light-hearted, in order to better subvert the dominant narratives engraved in the marble of the statues.

Bronze, 8 × 43 × 21 cm | 3 1/8 × 16 15/16 × 8 1/4 pouces / inches. Photo : Claire Dorn. © Iván Argote / ADAGP, Paris, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Maurizio Cattelan’s hidden son

With this resolutely provocative work, the artist continues a series of pieces in which humour vies with the absurd: we had already seen him in Nantes in the exhibition on kissing (6), where he treated us to a thorough licking of a Paris metro bar when we were expecting a more sensitive and sensual situation between two people (Altruism, 2011). But isn’t it the destiny of any artist worthy of the name to constantly deconstruct the pillars of a consensus that is certainly reassuring but ultimately leads to the sacralisation of things? Contemporary art is not exempt from this reification of revolutionary postures of their time, quite the contrary. Attacking great elders, as he did with this video work in which he ‘bombs’ two Mondrian paintings (Retouche, 2008), immediately places him on the side of the iconoclasts. This seminal performance was followed by numerous works, performances and actions, such as the one mentioned above, in which the figure of the ‘discoverer’ of America is consciously targeted as the initiator of predatory colonialism. One cannot help but think of Maurizio Cattelan, a master of provocation of all kinds, who has relentlessly attacked representatives of authority, especially the papacy, to which he has devoted particular attention. Like the Italian artist, the Colombian has chosen to use humour, absurdity and derision to produce powerful and polyphonic works, without falling into the trap of unambiguous subjects and messages: his proposal for the Voyage à Nantes is in the same vein.

Video. Durée / Duration : 00:01:20. © Iván Argote / ADAGP, Paris, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

1. Fabrice Gaignault, ‘Crimes et chafflements’ (Crimes and Chafflements), Transfuge, no. 160, September 2022, pp. 124-129.

2. Valérie Bussman, ‘L’art pour changer la ville’ (Art to Change the City), Entre les lignes. Le parcours artistique du tramway parisien (Between the Lines: The Artistic Journey of the Paris Tram), Zéro2 éditions, 2016, p. 366.

3. ‘There is no artistic practice that is not embedded in cultural mechanisms. These mechanisms are linked to the system of cultural domination which, in our societies, is one of the main sources of social hierarchies.’ in Geoffroy de Lagasnerie, L’art impossible, Paris, PUF, coll. ‘Des mots’, p. 32. For a critique of this book, see: Antoine Bonnet, ‘L’impossible impossibilité de l’art,’ 02, Autumn 2020 and online, https://www.zerodeux.fr/news/limpossible-impossibilite-de-lart.

4. According to the mantra of Jean Blaise, founder of Voyage à Nantes and director until 2024.

5. ‘Un été au Havre’ seems to be the best illustration of the spread of the concept created by Jean Blaise in his beloved city of Nantes. The mayor of Le Havre, who is also president of the Horizons party, seems very keen to welcome contemporary art to his city… unlike his number two, Christelle Morançais, who decided, as we learned in December last year, to destroy anything resembling culture throughout the Pays de la Loire region.

6. ‘Sur tes lèvres’ (On Your Lips), curated by Vanina Andreani, Eli Commins and Claire Staebler, Frac des Pays de la Loire/Lieu Unique, Nantes, 25 October 2024 – 12 January 2025.

Head image : Iván Argote, Dinosaur, 2024. Sculpture : Aluminium, armature en acier galvanisé, peinture automobile, vernis transparent aérospatial / Aluminum, galvanised steel armature, automotor painting, aerospace clear coat, 487 × 243 × 304 cm | 191 3/4 × 95 11/16 × 119 11/16 pouces / inches. Socle / Plinth : Revêtement en béton sur structure en acier / Concrete cladding on steel structure, 152 × 292 × 292 cm | 59 13/16 × 114 15/16 × 114 15/16 pouces / inches. Photo : Timothy Schenck 2024. © Iván Argote / ADAGP, Paris, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Yan Tomaszewski, Thomas Giraud - Avec Bas Jan Ader,

Related articles

Lucas Arruda

by Vanessa Morisset

Biennale Son

by Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

by Vanessa Morisset