Ndayé Kouagou

« Who is this person you ask ? »(1)

“A door that opens a little and closes badly”. Ndayé Kouagou sometimes chooses this periphrase to define himself. But beyond this flimsy door, we’re also interested in what happens on either side of it to understand his artistic approach. On the one hand, there’s a character he’s created, a harlequin with a new look and new clothes, who has swapped his antics for existential questions, uttered like advertising messages and staged in performances or short videos. On the other hand, the artist’s profession, the considered and rationalised choice of art as a career, with professional objectives. Pragmatic without being opportunistic, his method and the career path he has built for himself run counter to the social reality of art schools, where not all students have the same social starting opportunities. A report published on 21 January 2021 by the Cour des Comptes2 (French Court of Auditors) points out that only 20% of grant-holders are admitted to the three Paris art schools. Because they do not have the same economic, cultural or social capital, these students all too often wrongly disconnect artistic practice from artistic employment.

Ndayé Kouagou’s background is in fashion, the start of an artistic career in an environment that is supposed to be closer to him and more accessible. He worked for a few years as a motion designer, before changing course, fed up with the constraints, hierarchies and economic imperatives that curb all creativity. It was decided that he would become an artist, without having been to art school, without having learnt to master plastic techniques, without having been trained in aesthetic discourse, without any formatting or romanticism. Self-taught, his personal training was built up through contact with artists he managed to identify here and there, his vision still escaping the prism of recognition and visibility. He asked them a simple question: “How do you become an artist?” He develops a relationship with some of them, like Paul Maheke, who introduces him to different atmospheres, from a vernissage at the Palais de Tokyo to setting up the inaugural exhibition at Lafayette Anticipations. Ndayé Kouagou sharpens his senses and becomes aware of the variety of possible mediums that creation can take. With the feedback and encounters he receives, he refines his project and underpins his strategies with intelligence and precision. What can he do? What can he count on? Not painting, drawing or sculpture, but his words. The word that, ironically, he says, already distinguished him in the mouths of his teachers when he was at school. His exploration led him to the voice of Hanne Lippard, a near-revelation that confirmed his intuition for this medium of text written and then put into form. Familiar with self-exposure through his experiences on musical stages, it was with his performing body that his writings were first transformed into something else. Writing, almost automatic – daily without being thought of as an artistic practice – accompanies him everywhere, most often in English, sometimes in French. Fragments and snippets that he treats in a second phase of rewriting, like samples that he assembles, then refines according to the potential drifts and ‘systems’ that he develops as he goes along.

First system: conversational performance. The most direct and obvious presence of interaction with others. Centuries after the golden age of the art of conversation, the pride of classical French culture during the Enlightenment, Ndayé Kouagou uses address, apostrophe, questioning and back-and-forth dialogue as his performative tools. His method was soon perfected, moving towards total interrogation, to which the audience could first respond with a yes or no, then with a move, dividing the audience into two camps and gradually widening the number of possible participants. Common in Instagram reels and on TikTok, this practice of dual choice goes beyond simply expressing our preferences, by pointing or going left and right, it highlights the abyss of our desires and our quests to define ourselves: “Where to go and how to get there?3”

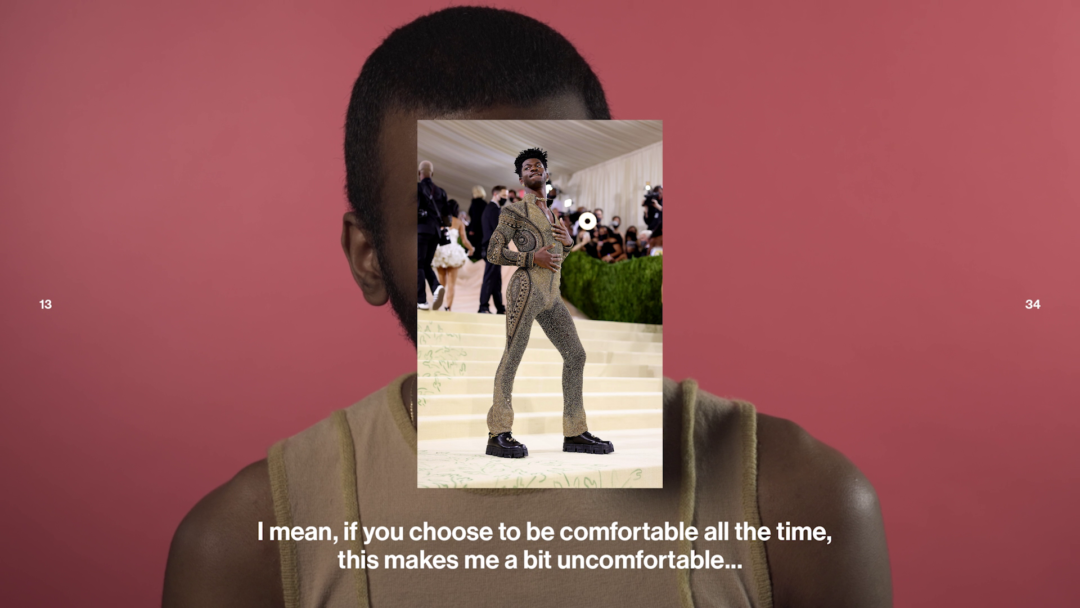

Video quickly became the second system, motivated as much by Covid’s health measures as by the economic reality of performance, perhaps even more precarious than other forms of creation. In his videos, he takes up the themes of definition and positioning that are dear to him. The character in the video A Change of Perspective (2023) first appears in a white crop top, scrolls from left to right, disappears from the frame and reappears at the initial end dressed in a yellow mackintosh; four costumes follow one another, depending on the character’s movements and the editing effects, like so many possible roles and social situations that condition our ways of reading and interacting, complicating the definition of self, which cannot be Manichean.

It’s also a realisation of the legitimacy of the profession, a decompression that in turn leads to other systems. Graphic design and typography follow suit, as the text assumes its materiality in plastic productions and is elevated, subito, to the rank of an identifiable logo. Around the videos, the paintings create specific moods, as in Will You Feel Comfortable in My Corner? (2020) in installation II. Le Coin in the exhibition ‘A Change of Perspective’ at FRAC Île-de-France (21.09.23 – 18.02.24), curated by Céline Poulin, the artist’s first solo show. The concept of the corner is brought to life by a shelter of textiles stretched over futons. Another system, the workshop, makes room for other people’s texts and amateur creative expression. The artist has defined various protocols for running her workshops. One of these involves asking participants to shed their first names and replace them temporarily with the names of objects, thus keeping at bay the symbolic weight of our naming and what it reveals about us and our social assignment, even before we have spoken.

Our self-image also becomes an ultimate system, a branding that irrigates others, right down to her Instagram account, youngblackromantics, almost a branded product. Lately, the artist has been experimenting with deferred exchange, offering visitors the chance to write questions to her by email from an iPad, introducing the form of remote conversation, a mix between epistolary exchange and chatbot. Driven by a constant need for updating, his ‘systems’ are gradually proliferating, and this need for transmission is being extended to new media. His current desires lead him to experiment with performance by several people, so that he is no longer the sole protagonist.

Each system requires specific skills, and the artist surrounds himself with a team, playing the role of conductor who brings together its members without ranking them. Composed of an artistic director (Axel Pelletanche), a director (Romain Cieutat), stylists (Ally Macrae and Mélodie Zagury), make-up artists (Oldie Mbani and Maty Ndaw) and a director of photography (Matéo Colzi), the specialised organisational model is borrowed from that of fashion studios, but differs in the friendly nature of the relationships. His solo exhibition at the FRAC takes us on a journey through these multiple ‘systems’, from screens to paintings, from installations to the free practice table. Based on the principle of “The book you are the hero of”, the artist has created a way for the public to circulate and move around, as initiated in his performances, by moving from one room to another according to the choices on offer. The spaces are ordered by the cryptic numbering of an argumented plan: I. The Choice, II. The Corner, IIIa. The World, IIIb. Change, IV. Thought. The treasure hunt is also made possible by an internal progression specific to the videos and the evolution of the character he embodies on screen.

Ndayé Kouagou does not put himself on stage; on the contrary, he visualises himself from the audience’s point of view. In turn – or all at once – influencer, youtuber, coach, presenter, he gives way to this character, who has no name, no age, who slides from one binarity to another with the dubbing of the voices, done by Salber Lee Williams and Pascale Clark. Freed from characteristic traits, he exists as an aggregate of identities, outside established paradigms, in which everyone can find themselves. Separated from himself, the only personal reference the artist confides has become a joke: in his stream of words, he saves one sentence for his mother. His character is deliberately contradictory and ambivalent, alternately hesitant and injunctive. “Doubt never leaves me”, he says in the video Will you feel comfortable in my corner? (2020), and he generously sows doubt in our convictions. The artist is not driven by a regime of unambiguous truth, and his questions do not call for answers, except for confused and unstable ones. He also bets on delayed answers and shifts in temporality, thwarting our thirst for permanent instantaneity. The interaction we seek implies a displacement of intentions, which the artist aspires not to control. In IIIb. Le Monde, many of the photographs of the aluminium mural, Looking at two sides of the same coin is not exactly looking elsewhere, were taken by visitors. “What a beautiful world” seems to have attracted more attention than the rest of the sentence “We live in, right?”, creating some comical and surprising discrepancies that the artist finds amusing. Making the text autonomous is an integral part of his intentions, and he prepares the ground for these derivations from the audience in his paintings. His desire to extend the text feeds into his plastic works, lettering mixed with textiles set in resin and placed under glass, which may or may not surround the videos.

The spoken and written content is enhanced by a finely orchestrated staging: a set up, a scenography, a different style each time. We move from a semblance of a living room, evoking a fictitious programme, Good People TV (2021), which he is supposed to host, to a studio where the recording and lighting equipment has not been put away in A Coin is a Coin (2022). In the first, the technical indications for editing appear, and in the second, the backstage is left visible. It would seem that the harlequin he plays is taking us into the confidence of his artifices. The content was created using the techniques and tools of social networking. The first videos are centred on his nose, and the camera moves according to the movements of his face, tricks that dancers normally use to fix the video at their centre of gravity. By appropriating digital marketing strategies and aesthetic codes for his own artistic ends, he defends his own game in the attention economy, peppering it with anomalies. It’s a near-perfect YouTube tutorial, with one detail that doesn’t quite add up, like his face suddenly hidden by large text. Internet culture punctuates his speech, with memes, emojis and a certain colourimetry.

“Of course the question is why, it’s always why, but, why not?4 – the force of the words and, above all, the repetition of interrogative phrases, coupled with massive question marks, plunge us into a RealTime mode, to use the expression of researcher Eloy Fernández Porta. A relationship to time that is familiar to us, because it is expressed in every aspect of our daily lives, in this age of afterpop: in loops, in certain series narrations such as those in The Simpsons, in infinite loops, in video surveillance… From his flow, interrupted only by silences filled by fictitious responses, emerge common references, Airbnb or hotels; shared experiences, that of being on the corner or in the centre. Incongruous examples and innocuous turns of phrase touch on deeper realities: vulnerability, legitimacy, social comfort or discomfort, authority, domination. The installation La Pensée (2023), made up of eight suspended texts, is part intimate confession, part personal development rhetoric, and deals with classic and aesthetic oppositions: good/evil, god/devil, responsibility/disengagement, order/disorder, and so on.

His discourse is complex, a joyful mix of reasoning by the absurd and syllogisms: “It’s just logic!” he exclaims in I’ll only swallow my own fluid (2021); humour and irony, both existential and superficial, but never inaccessible. His starting point is always his own personal position, a reflection of the social experience of certain racialised or sexual minorities, transposed again and again, until everyone – “from his mother to his uncle in Marseille” – can pick out what he or she wants: a slogan, an aesthetic, an accessory. Several levels of discourse are superimposed, evident in the framing and video effects, or in the body movements and vocal tones. They are intimate and collective, somewhere between introspective thought in the making and the assertive sermon of a guru: “Do you want to be a good person? 6”

Through her abundant and singular practice, Ndayé Kouagou assumes her sincere desire to bring people to art, not simply as an audience. On the contrary, this spectator experience seeks to put them on the path to practice. By hijacking the tools used to produce content, Ndayé Kouagou is encouraging us to do the same, to unleash our active creativity through the reconsideration of basic, infraordinary forms: sounds, words, thoughts, glances.

1Extrait de la vidéo A TO Z, stéréo, 4’13’’ min, 1 canal vidéo, 2023.

2Cour des comptes, « L’enseignement supérieur en arts plastiques », décembre 2020.

3Extrait de la vidéo Good People TV, installation vidéo, 7’23’’ min , 2021.

4Extrait de la vidéo I’ll only swallow my own fluid, 2’07’’ min, 1 canal vidéo, 2021.

5Conversation avec Ndayé Kouagou, Harilay Rabenjamina et Flora Fettah, bruisemagazine, 19.07.2021 : https://www.bruisemagazine.com/article/ndayé-kouagou-harilay-rabenjamina].

6Do you want to be a good person?, verre, vinyle, tissu, résine, aluminium, 80 x 60 cm, 2021.

______________________________________________________________________________

Head image : Ndayé Kouagou, A Change of Perspective, 2023, ©Martin Argyroglo, Callias Bey, courtesy of The Artist and Frac Île-de-France

- From the issue: 106

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Julien Creuzet, Chloé Delarue ,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset