Skulptur Projekte in Münster 1977-2017

A research laboratory for art in public places

Every ten years, and for a few months, over the past 40 years the city centre of Münster, in Westphalia, is turned into an open platform for art and reflection about relations between artists, city and public. Seen as a research laboratory on “art in public places”, this internationally renowned exhibition has influenced many events. The first such exhibition was violently criticized at a local level, but these days “Münster” has become an institution, and a leading player in the city’s cultural life.

1977: The challenge of the Skulptur Ausstellung in Münster

Donald Judd, s.T. / Untitled, 1977. Installation permanente, rive ouest du lac Aa / permanent installation, western shore of lake Aa. Photo: Valérie Bussmann, 2017.

Münster is a commercial city with a major university. The identical rebuilding of the city centre, which was largely destroyed during the Second World War, is symptomatic of an attachment to tradition and history. The first exhibition, Skulptur Ausstellung in Münster, was launched in 1977 by Klaus Bussmann, at the time a curator in the Münster museum, after much violent argument opposing the installation of a kinetic work by Georges Rickey. The intention was to make up for lost time by initiating local people in modern and contemporary sculpture. The exhibition was above all the outcome of an historical and didactic vision. The issue was to democratize access to art by opening the restricted setting of the museum to a broader public. It was based on three strong themes: a first part, inside the museum, retraced the genesis of 20th century sculpture; the second section, devoted to the “autonomous” sculptures of the 1960s and 1970s, was installed outside; and the most innovative part, produced under the aegis of Kaspar König, then a young curator living in the United States, was given over to “projects”. The invitation made to ten artists, most of them American and still partly to some extent unknown,1 to devise a sculpture for a place of their choice within the city, was a significant challenge. Despite the furious initial controversy, the exhibition’s local and international success persuaded the organizers to carry on the 1977 “experiment” ten years later, and repeat the “projects” section. Its experimental and process-oriented nature was confirmed once and for all in 1987, and thenceforth called Skulptur Projekte. The basic principle and the way it is applied have been maintained up to the present day.2

A work-in-progress for site-specific work

The exhibition differed from similar programmes because of an approach that was at the time unusual: what was involved, initially, was to counter a museum-based and decorative approach to the works, arbitrarily placed in green areas, in squares, and in front of buildings. Instead of using existing sculptures, as was often the case, the artists were asked to come up with a novel work, produced in immediate interaction with the site’s specific data. To this end, they were previously invited on the spot in order to become familiar with the local situation. In other respects, they were neither subject to any general theme, nor to any predefined place. They were left entirely up to their own devices in relation to the aesthetics, form, materials and subject. The matter of the work’s time-frame and permanence was not raised as a matter straightaway: the organizers undertook to produce the works, and the artists would remain bare owners of them. This said, some forty sculptures remained in place at the end of the exhibition. The approach championed by the curators responded to trends emerging in the late 1960s: the notions of in situ and site specificity, which would assume greater scope during the 1980s, and in the end become an essential sine qua non condition for public art from the 1990s on. The repeated organization of the Skulptur Projetke every ten years makes it possible to conceive of this event not as a clearly defined “exhibition”, governed by a general subject, but rather as an experimental work-in-progress. While factoring in the trends of the day in each exhibition, thanks to this ten-year time-frame the exhibition lends itself to a long-term field survey. On the one hand it makes it possible to record the development of the notion of sculpture, and, on the other, to draw up an inventory of the relations between art, city and public. Münster thus offers a chance to observe “how thinking about sculpture has successively shifted towards a questioning of the structures of space and other public domains.” (Kaspar König).

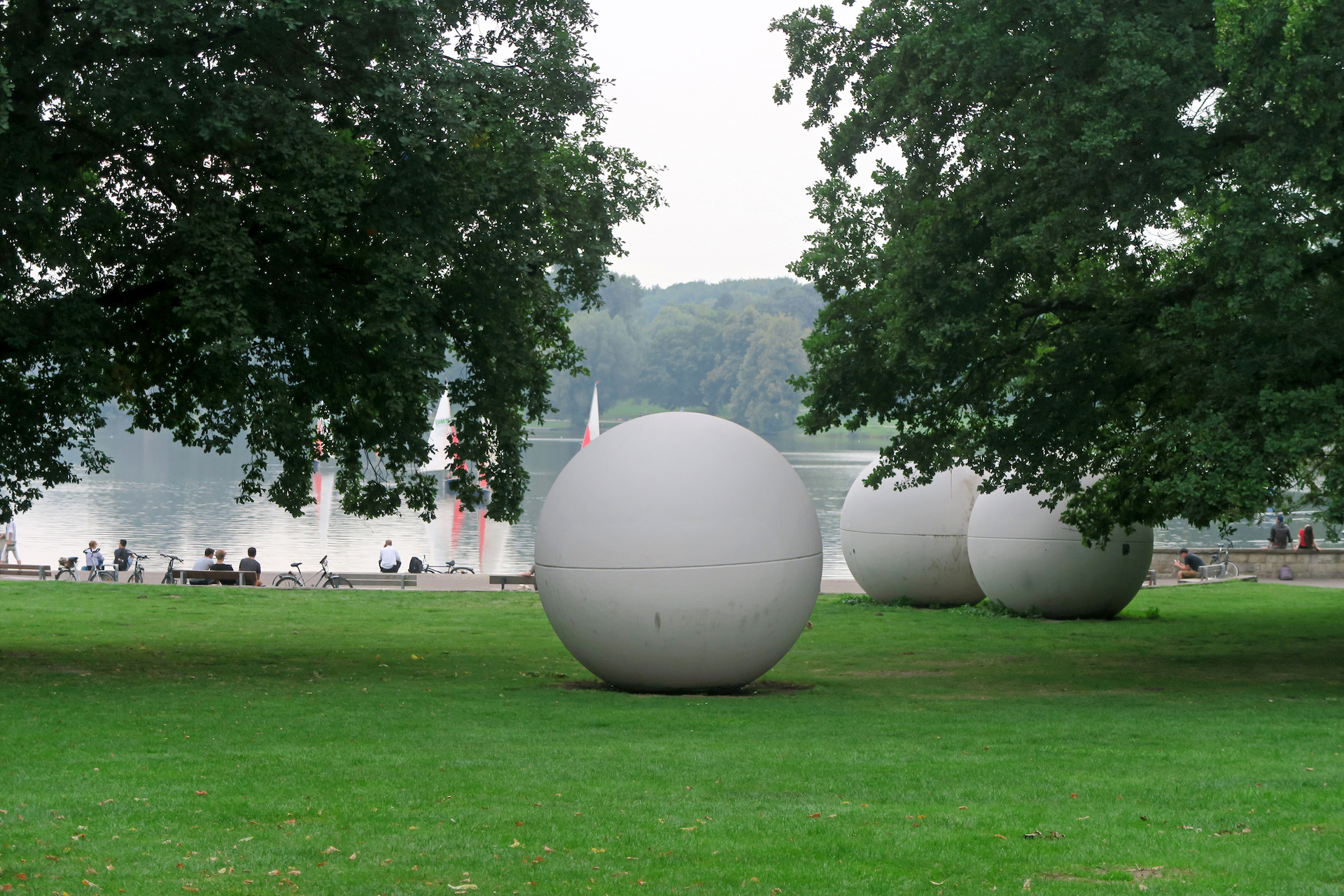

Claes Oldenburg, Pool Balls, 1977. Aaseeterrassen. Acier renforcé / Reinforced concrete. Trois balles de 3.5m de diamètre / Three balls, each 3.5 m diameter. Photo : Valérie Bussmann.

1987: “From park to carpark”

The second exhibition revealed a significant development: whereas that initial 1977 exhibition was marked by minimalist stances, artistic activities now became diversified. The number of artists who had already worked in public places had risen considerably. In 1977, the curators still made a differentiation between autonomous sculpture and contextualized works, but ten years later, site specific sculpture and art in public places were henceforth synonymous. In 1977 there was a prevalence of works creating an above all formal link with their environment (Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Richard Long, Ulrich Rückriem, Claes Oldenburg). Most of the artists taking part in the 1987 exhibition developed a basic and more tangible approach to the city. The artists formally and conceptually questioned history, culture, architecture, and urban and social organizations. They revealed the imprints of the past left behind on the urbanistic plan (Daniel Buren) and embarked on a dialogue with historic monuments (Richard Serra, Sol LeWitt). Some undertook a task of memory by paying tribute to personalities who were important for the local identity (Ian Hamilton Finlay, Jeff Koons, Keith Haring). Also involved was making historic places accessible and recalling episodes from a less glorious past (Lothar Baumgarten, Rebecca Horn). The traditional notion of the monument was challenged, often with an ironical wink (Richard Artschwager, Thomas Schütte). The boundaries between art, design and architecture were broken down (Isa Genzken, Dan Graham). The works could be ambivalent, involving an at once artistic and functional value (Scott Burton, Siah Armajani, Dennis Adams). Artists also worked in the landscape (François Morellet, Maria Nordman, Ludger Gerdes). In a postmodern spirit, references to history, narration and figuration, and irony and appropriation were all on the agenda (Thomas Huber, Robert Filliou, Nam June Paik, Katharina Fritsch).

1997: The city as a (counter-)narrative of an event-focused culture

Jorge Pardo, Pier, Installation, 1997. Rive sud du lac Aa / West bank of the Aasee, south of the Annette-Allee. Photo : Valérie Bussmann.

In 1997, the Skulptur Projekte were a definite fixture on the international scene. With more than 70 participants, the city was truly afloat in sculptures. What was involved was a questioning of art’s relation to the public in the face of growing globalization and the way the media were developing. This exhibition was generally regarded as a “festival-like exhibition”. The new generation of artists took over the city with enthusiasm and without any kind of inhibition, in order to celebrate “the farewell to urbanistic euphoria” (Walter Grasskamp) of the previous decades, through the immediate encounter with the public. Many artists stepped back from the notion of “art in public places” as it had been hitherto employed. The in situ practice became a “common place” which had to be revisited. Site specific sculpture was replaced by action and spectacle, the ephemeral and the temporary.

Andreas Siekmann, Trickle down. Der öffentliche Raum im Zeitalter seiner Privatisierung (Trickle down. Public Space in the Era of its Privatisation), 2007. Installation temporaire, Cour d’honneur du Erbdrostenhof / temporary installation, main courtyard of Erbdrostenhof. Courtesy Andreas Siekmann ; Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin.

The contextualization of works was thus effected through the creation of interrelational networks. Art went towards the public and put itself at its service. Communication and participation lay at the heart of many projects (Marie-Ange Guilleminot, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Yutaka Sone, Reinhard Mucha). The interplay involving ambiguity, irony and derision was intended not only to entertain but also to summon an effect of distancing stimulating a critical approach (Andreas Slominski, Roman Signer, Tony Oursler). The artists occupied both outstanding sites (Nam June Paik, Bert Theis) and abandoned places, in order to create new situations and spaces available for people to meet in, and indulge in leisure activities (Jorge Pardo, Tobias Rehberger), or for meditation (Peter Fischli & David Weiss, Hermann de Vries). As in 1987, intervention in the daily round was made in particular through reconciliations with architecture and the creation of at once functional and sculptural objects (Per Kirkeby, Tadashi Kawamata, Wolfgang Winter/ Berthold Hōrbelt), wavering between utilitarian and visionary design, both lasting and temporary (Atelier Van Lieshout, Stephen Craig, Franz West, Kim Adams). The works (Ilya Kabakov, Janet Cardiff, Allen Ruppersberg, Maurizio Cattelan, Mark Dion) invited people to an “urban drift”, discovering the city through a literary and poetic stroll, at once real and imaginary. Other stances were more political and critical. While undertaking field work, they asked: “To whom does the public place belong?” The work attracted attention to the gradual privatization of city centres (Maria Eichorn) and questioned the overlap between public interest and corporate economy. During the 1990s, people witnessed a growing interest in open air art events. “Public art” became a reference, and an important challenge that was political and economic. Henceforth, the exhibition risked becoming ensnared by its own popularity, and taken over by the City’s marketing departments.

2007: The disappearance of the public place

The issue of the (exploitative) use of art for the promotional purposes of cities and private companies lays at the heart of the lines of thinking behind the 2007 Skulptur Projekte. The starting point was the fact that the “public place”, subject to privatization and a growing corporate spirit, was gradually vanishing as a democratic entity. The current term “art in public places” was now unusable for artists and curators alike. The exhibition was thus declared to be a free zone in order to contrast the functionalization of art in the public place with a new conception of autonomy; according to curators, it was “performative, media-oriented and reflexive”.3 Participatory art moved to the background in favour of performance (Pawel Althamer, Doria García, Michael Elmgreen & Ingar Dragset), and film references to the city played an important part (Clemens von Wedemeyer, Eran Scharf & Eva Meyer, Valérie Jouve). Many interventions worked their way into the city in a subversive manner. Realist fiction tested our perception of the urban environment, greatly manipulated by standard images, produced in particular by artists on behalf of advertising agencies (Annette Wehrmann). The acoustic or sound installation became a form of aesthetic resistance to the sound pollution of the urban environment (Susan Philipsz). The usurpation of urban areas by the private sector, especially in the wake of the outsourcing of public services to specialized firms, was the subject of many works. They were opposed to the uniformization of cities by the reconfiguration of public places so as to make them more attractive in relation to the predominant standard furbishment (the toilets of Hans-Peter Feldmann). Another form of ironic protest was the crushing of advertising signs and kitsch sculptures invading cities to make of them a new monumental work—a gesture of liberating “vandalism” against the commercialization and aesthetic disfigurement of city centres, especially by a so-called “urban” art in the name of marketing departments (Andreas Siekmann). Despite the critical approach, the exhibition had trouble imposing an effective response to communal marketing strategies. Defined by a festival atmosphere and one of tourist promotion, it lost all its critical potential. Art intent on involving protest was finally overtaken by the economy of beautification, and the leisure culture.

Alexandra Pirici, Leaking Territories, 2017. Performance, Salle de la Paix de Westphalie dans l’Hôtel de ville de Münster / performance, Friedenssaal in the Historical Town Hall of Münster. © Skulptur Projekte 2017, Photo : Hanna Neander.

2017: “Instructions for surviving the digital age”

Cosima von Bonin / Tom Burr, Benz Bonin Burr, 2017. Installation temporaire, parvis du LWL-Museums für Kunst und Kultur / temporary installation, forecourt LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur. Photo : Valérie Bussmann.

Aram Bartholl, 5 V, 2017. Feu de camp, bois, acier, générateur thermoélectrique, cables, composants électroniques / Campfire, wood, steel, thermoelectric generator, cables, electronics.

The 2017 exhibition is exploring the speeded-up media developments of the past decade, and in particular the influence of digitization on “the body, time and the site”.4 Faced with this development which includes a drastic shift in the boundaries between public and private, it focuses on the physical dimension, interaction, and immediate communication. In addition to digital art, multi-media installation and film, it envisages a broad spectrum of performative practices, be it in the form of interpretation and presentation (mise en scène) (Gintersdorfer/Klassen, Alexandra Pirici), creative processes (Koki Tanaka), or by inviting the public to experience an immediate bodily sensation (Ayşe Erkmen, Nora Schultz). The roles are reversed between actor and spectator, with the latter being the object of “direct actions” (Gintersdorfer/Klassen).

The actor, on the other hand, himself becomes a search engine (Alexandra Pirici). Sculpture comes with different faces: “living sculptures” walk in the street (Xavier Le Roy), while others appear in the form of robots, as auxiliaries of human beings (Hito Steyerl). The monumental gives rise to a twofold discussion about public art and genre (Nicole Eisenman, Nairy Baghramian) as well as to an ironical revision of modernist sculpture, this latter awaiting its repatriation by truck (Cosima von Bonin/Tom Burr). The references, formal and conceptual alike, are immanent to the works. The artists make use of building sites and abandoned industrial plots (Christian Odzuck, Oscar Tuazon) and interior spaces—an old shop selling Asian products (Mika Rottenberg), a dance hall (Barbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca), an old skating rink (Pierre Huyghe), and the foyer of a large bank (Hito Steyerl). While being signally linked to the Münster context, these interventions relativize our perception of the world by reconciling the local and the global, and vice versa. They act as an interface between periods and places, times and spaces, tangible and virtual things, and public and private things. They reduce the distance between worlds, by digging tunnels between two countries (Mika Rottenberg), building a bridge between two river banks (Ayşe Erkmen), or by running workshops in order to experiment with “possibilities of cohabitation” between people of different origins (Koki Tanaka). The exhibition is also part and parcel of the demystification of technology, by presenting “instructions for surviving the digital age” (Aram Bartholl).

Compared to many exhibitions with explicitly political, and not always persuasive, intentions, the Münster show is pleasantly accessible and relevant. And even if it does not directly display any political argument, this does not stop it from being political. It is in this sense that Skulptur Projekte has been operating since 1977 in the public and for the public, independently of political and economic interests, so as to make free spaces available and call for a fruitful encounter between artists, city and public. In the face of the increasing number of major international exhibitions, this outdoor event is still a landmark, a ship imperturbably making its way in time’s current.

1 Carl Andre, Michael Asher, Joseph Beuys, Donald Judd, Richard Long, Claes Oldenburg, Ulrich Rückriem and Richard Serra.

2 In order to provide the project’s location, on the one hand, and, on the other, an independent action with regard to politics and the art market, the Münster museum is the lynch pin behind the undertaking. The projects were executed under the concerted supervision of a Münster museum curator (1977-1997 Klaus Bussmann, the museum’s director from 1985, in 2007 Brigitte Franzen and in 2017 Marianne Wagner, modern art curators) and one or more outside curators (1977-2017 Kasper König, 2007 Corinna Plath director of the Kunstverein in Münster and in 2017 Britta Peters, a freelance curator) with the backing of both public agencies and, in certain cases, private collections.

3 Brigitte Franzen, Kasper König and Corinna Plath 2007. The number of artists was lowered to 35 instead of 60 in 1987 and more than 70 in 1997.

4 For the first time another city was associated with the exhibition: Marl, an industrial city in the Ruhr completely rebuilt from scratch after the Second World War, which, from the outset, readily incorporated art in the public place.

(Image en une : Daniel Buren, 4 Tore (4 Portes / 4 Gateways), 1987. One door permanently installed in Domgasse. Photo: Valérie Bussmann, 2017.)

Related articles

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret