Drifting all dressed up: portrait of the artist as a nomad

Perched on its padded suitcase on rollers, a creature wearing Ugg boots snorts. Behind its blond mane, we can make out a smiling, toothy grin. But this grin is in no way addressed at us. No: it is totally directed at the selfie stick, a robotic limb that surveys the pyramidal composition. Like it, everything here is articulated, foldable, built-in, strengthened at the angles, and mounted on rollers. Looking at this aerodynamic carapace, it’s hard to tell where the human starts and the artificial ends. The whole thing is self-justifying, like a human race that has ended up mutating by dint of being stuck in the limbo of a perpetual transit. If the image seems familiar, it still describes a very precise body of works: the sculptures of Anna Uddenberg’s Transit Mode—Abenteuer series (2014-2016). Those same sculptures which greeted visitors to the 9th Berlin Biennial from the glass hall of the Akademie der Künste in 2016. Behind the mannered hyper-realism of the form and the grotesque effect of certain cultural signifiers (the Uggs and the candy-pink anorak of the “basic white girl”), a certain self-celebratory pitch came across above all else, the same pitch that also imbued all the works presented at the said Biennial. Probably a semi-conscious caricature but especially a pleasure in belonging to an extremely privileged fringe of the populace: the neo-post-Internet artist whose studio is her laptop, her home address being WiFi waves.

Dismembering the comforting object by a “nomadism of action”

The topos of the nomadic artist did not come into being with the new millennium. Back in 1944, in their Dialectic of Enlightenment, Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer wrote that “those who practice it become vagrants, latter-day nomads, who find no domicile among the settled.” The two philosophers fled their native Germany during the war, so the book was written in exile in New York. In it, in the form of fragments, a critique of totalitarianism is developed and, by extension, a criticism of the obsession with totality embraced by philosophy. The spirit of the Enlightenment cannot be perpetuated forever, it is bound to turn into its opposite: barbarism or magic. Art, and a fortiori contemporary art, thus appears like a potential outcome for reason, as long as it fully encompasses mobility and break-up: everything that philosophy, dedicated to having systematicity in its sights, fails to underpin. The theses championed by the two authors, which were relatively private when the book appeared, and cold-shouldered by the academic world, would nevertheless enjoy an effective posterity in the field of art. In tune with the practices of Arte Povera in the 1960s, the book became a key reference thanks to the critical pen of Germano Celant—the same person who gave the movement its name in 1967. And made the nomad the main conceptual figure of his theoretical system.

Invited to show his work at the Negev Museum of Art at Be’er Sheva in Israel, Jannis Kounellis arrived, to borrow his own words, “with his hands in his pockets”. Ever since his early works of the 1960s, and throughout his life, the context would entirely determine the orientation given to the project. Early in 2017, the artist’s modus operandi had not changed. Fascinated by the stones scattered in the nearby desert, he took them inside the museum. Connected by thick ropes running along the floor of the two levels made available to him, Kounellis set some of them on pieces of furniture found in the neighbouring flea market. As is often the case in the artist’s grammar, the furniture acted as substitutes for an absent body while the upright stones imitated by their verticality a semblance of two-legged presence. “In the late 1960s, Kounellis’s motifs tended to oscillate between references to the primitivism of Mediterranean shepherds’ dwellings and references to the imprisonments that followed the coup d’état of 1967 in his native Greece”, wrote Romy Golan in the columns of Artforum, reviewing the exhibition.1 And for good reason Germano Celant would refer on several occasions to his praxis as a “nomadism of action”.

In December 1979, again for Artforum, the same author published his portrait of Mario Merz under the title “Mario Merz: The Artist as Nomad”. By focusing on the appearance of the igloo motif in his work, this latter showed how the form, which was at times transparent and made of glass and aluminium and at others battered when made using flax sacks sewn together, contradicted the very brief of the habitat: between interior and exterior, between private and social, between nature and culture, there is no separation. On the other hand, the intrinsic porousness forces metabolic exchanges between the different environments. “A shelter and a cathedral of survival, from the politics of art as much as from the winds, such buildings are also the image of the nomad or vagabond, who does not believe in the secure object, but in the dynamic contradiction of life itself. For nomads, the vagabond’s existence means drifting from one context to another, adapting to local foods and customs; their lifestyle never crystallizes into anything definitive or stable”.2 As a guerrilla attitude challenging the embryonic consumer society, Arte Povera borrowed for itself the latent implications of the theses on art put forward by Adorno and Horkheimer, for whom, it just so happens, art finds its anti-establishment strength by linking back up with magic, while replacing its closed system by an open network of signs. Or, to put it another way, by constructing a withdrawn sphere, separate from the arena of current affairs. In embarking on the Objets Cache-Toi series—this being the title of those igloos he built between 1968 and 1977—, Merz also offered a glimpse of the first shift from object to subject, from roof over your head to solely your head. Although moveable, protection is no longer just that additional layer that you can take off or move as you wish: the roof starts to stick to the self.

The contemporary body is neither an organism nor a machine: it’s a techno-body

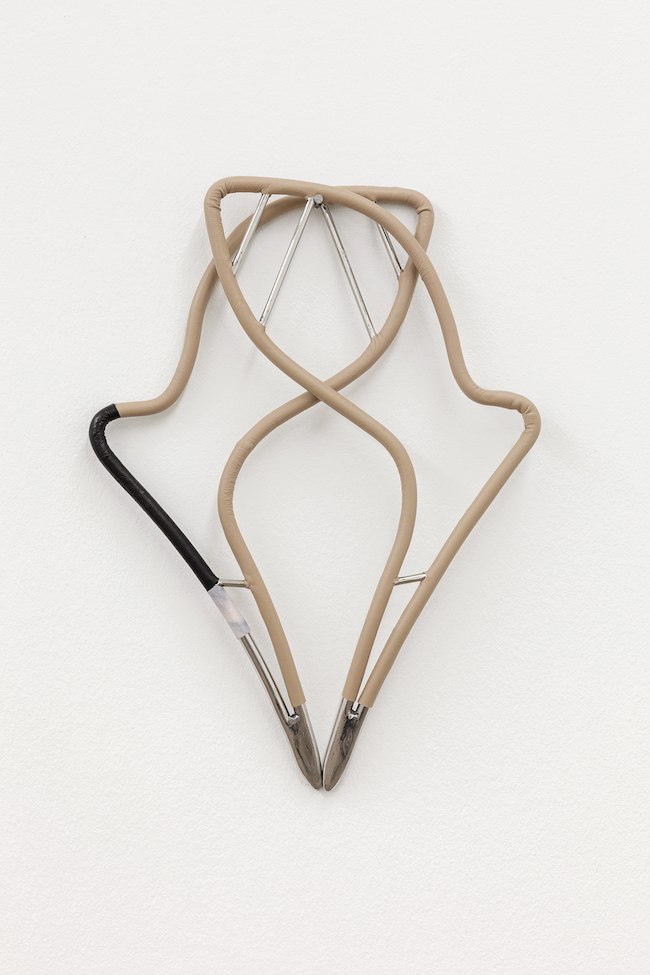

Jeanne Briand, Proximity Max, 2017. Motorbikes mudguards turned into nery and prostheses covered in leather, variable dimensions. Photo : Romain Darnaud.

In its earlier prefigurations, nomadism appeared essentially as a revolt against private property and the invasion of consumer society’s standardized items. Right now, a new meaning of the term is coming to the fore: the millennium just beginning has certainly marked humanity’s awakening to its nomadic condition—the whole of humanity and not just the artist. But this particular nomadism is no longer linked to the habitat, it is even its contradiction. It has become a biological datum and connects with the most common motif of augmented humanity—a term that is, incidentally, inexact, because it is more a question of synthesis than addition, linking up with the “production of affects”—biopolitical affects—referred to by Toni Negri and Michael Hardt. For the Paul B. Preciado who, in 2008, wrote Testo Junkie, under the name of Beatriz Preciado, the modern body cannot henceforth be “reduced to a pre-discursive organism”, and life “does not exist outside the interlacing of production and culture that belong to technoscience”. Whence his conclusion, based on the earlier works of Donna Haraway: “This body is a technoevolving, multiconnected entity incorporating technology. Neither an organism nor a machine: technobody”.3 The contemporary body is literally ‘born ready’: ready to drift.

These interweaves between theories, materials, molecules and affects are incarnated in the work of Jeanne Briand in the form of plugs and prostheses which create their own life. Embarked on during her degree at the Paris School of Fine Arts, the Random Control (2010-2015) series is made up of blown glass uteri manufactured from laboratory test tubes. The series then developed towards Gamete Glass (2015-2017), where forms likewise reminiscent of an artificial life produce sounds when they are activated by the breath that gave birth to them. In becoming more and more autonomous, these glass matrices were displayed augmented by plugs and supported by steel bars at the Salon de Montrouge in that same year. In attaining an exchange with other environments and verticality, the works in the series G.G.Opal Schwartz (2017) thus appear like the Objets Cache-Toi of the world after the disappearance of the human factor. But it is undoubtedly in the latest developments of her work that we can see in its most readable form the appropriation of the theme of biological nomadism by young artists who have begun producing during this decade. In a month-long residency at the Clark House Initiative in Bombay, last summer, the artist observed the mudguards wrapping the bodies of motorbikes being driven around the over-populated city. As both a protective device for the bike and a device for keeping pedestrians at bay, these external metal structures are, in addition, made to measure and customized. In covering them with skin, the artist hijacked them and turned them, in her own words, into “finery and prostheses”, and started a new series, Proximity Max, which she is currently involved with in Los Angeles. Set on a wall or on the ground, the originally augmented body has ended up disappearing altogether, elevating the prop to the rank of substance.

A temporary (and transportable) community of circulating signs

Sarah Ne ssa Belhadjali, The Dress, 2016. Printed poplin, 3D print, laser cut plexiglas, smartphone and app. Photo : Allia El Fani.

With regard to sex and sexual identity, Paul B. Preciado emphasizes the fact that there is no longer any hidden secret to be discovered: design and “sexdesign”4 take the place of unveiling. To a lesser degree, the biologization of nomadism, and its inclusion in the body, is also more simply incarnated in the status given to this kind of design: clothing and accessories take on a new meaning within an artistic context that is often reluctant to integrate them in a fully-fledged way—a legacy of a philosophical essentialism which, just like systematicity, nomadism smithereens. Nouvelle Collection Paris is the result of Sarah Nefissa Belhadjali’s desire to create a functional brand in order to present artists’ clothes and accessories. Initiated in 2016, when she was a student at the Paris School of Fine Arts, the artistic gesture is situated at the level of the brand’s creation: logo, Instagram account, lookbook, T-shirt for the staff, and specific hangers. So a context capable of accommodating the works of other artists, like an exhibition whose time-frame copies that of the event—namely, the fashion show. The first two collections, Spring-Summer 2017 and Autumn-Winter 2017-2018 pushed the absence of differentiation to its paroxysm, presented as they were during the Fashion Week in the main amphitheatre of the Paris School of Fine Arts, a place that is often privatized for such events, extending the collaboration to the necessary hairdressers, make-up artists and photographers in the fashion industry ecosystem. The artists decided to parade carrying their works—ranging from clothes more or less recognizable as such to sculptures henceforth made transportable by force of circumstance.

A temporary community of circulating signs. This is how Kevin Desbouis, who just graduated from the School of Fine Arts in Clermont-Ferrand this summer, for his part describes the four temporary tattoos that he is producing and then disseminating. Not a series but a different piece for each motif, which each function on a principle of unlimited publication: Untitled (portrait as absent), a coloured tattoo made from a photo of a painted figure whose texture is crumbling; MO(U)TH, a poem whose typography connects mouth and moth; Blister, a square taken from a zoom in a photograph re-using the look of a plastic object; Y, a figure of a man made using the letter taken from a 16th century alphabet grafted with emoji eyes, generational mascot of generation Y which is a bit at a loss for references (why?). With each one marked by a swaying of the form, by a consubstantial uncertainty guaranteeing the permanent motion, these tattoos, “almost like a bruise you might give yourself on your arm, with which you live for a few days, or a week, and which then ends up disappearing”, correspond, for the artist, to his way of working. “I wanted to produce a form of circulation which can be as light as the unfurling of life, meaning, and ideas, associated with the body and with people, which doesn’t bother with classic exhibition issues (which I sometimes find to be ‘out of sync with reality’)”, he explains. “The making of the tattoos, and the way I offer them or the way they are subsequently offered, summon up private and public social settings, contexts in which something other than the piece’s content is exchanged. There is a spareness of production and existence, which doesn’t rely on any already existing context, except life”. In drawing closer to the network of signs, the “politics” of “bio-politics” also rings out behind the possibly more immediately sexy “bio”. The adorned body is political because “there is no longer any naked life”, as Giorgio Agamben put it; because, through the combination of knowledge and techniques, either inherited or manufactured, which it contains, the body already holds a discourse about the world it is passing through.

Tarik Kiswanson, Everything I ever needed (fitting), 2017. Courtesy Tarik Kiswanson ; Lafayette Anticipation – Fondation d’entreprise Galeries Lafayette.

The theme of nomadism thus takes on a distinctly political hue in the work of Tarik Kiswanson, whose body of works forms a constellation organized around the evocation of an absent body, whose imprint is here also a vehicle of permanent mobility. From his penetrable metal sculptures, activated by the presence of the visitor’s body, the artist has kept the consciousness of the individual body as the first rung of the construction of a potentially universalizable identity. Right now, Kiswanson is designing a collection of clothes which will first be worn by performers—clothes and not “costumes”, he stresses—, but what is involved is in no way a disguise or a simulacrum. Because the collection can be independently presented, it is titled Everything I ever needed, with each one of the various looks being named, furthermore, by an individual title. Cut from the raw cloth that is usually used to manufacture patterns—the stage prior to the actual making of the garment as we will see it being worn—their sandy colour indirectly connotes the desert. As a return to an effective nomadism but nevertheless immediately part of the contemporary condition, several of the items of clothing are constructed around a museum tote-bag, be it incorporated in the belt, on a sleeve or on the back, in which it is then possible to fold up the entire outfit so that you can take it away with you. Twelve in number, but forming twenty outfits when combined, the clothes in the collection illustrate, as a sub-text, a sedimentation of history, lower case, and History, with a capital H. Of Palestinian origin through his parents, and born in Sweden, the artist belongs to the second generation of immigrants who have not undergone the experience of exile in a personal and physical way, but approach daily life in the cleft of an interstice which right away bars any sense of belonging. In fact, be it in his sculptural work or in the texts for his performances, nothing is stable, but nothing is hierarchized, either: counter-form becomes form, one and the same motif is expressed in several sizes, and the theme of emancipation is incarnated both in a fragment of text evoking geopolitical boundaries and in the melancholy of a train journey.

So the question is not so much—as was the case in the 1960s—to do with no longer wanting to add objects to the world, but rather involves the ill-suited character of this extreme sedimentation represented by the display of artefacts detached from the body, and unsuited to contemporary flows. The object, the work (the difference matters little, they are connected by use) is not disqualified but wrenched from its “soil”, and from the oneness of its context of emergence. With regard to Vincent Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, Jacques Derrida notes, in The Truth in Painting, that the boots are unlaced, abandoned, well-worn and at a loose end; that they cannot be “put back on”, or assigned to a subject, and that they will accordingly remain open to every manner of interpretation, belonging to nobody and being content to be in a tracery of inside/outside which he calls “stricture”. As he suggests, it is up to us, in our turn, to learn how to let works exist in their detachment, without wanting to re-appropriate them for ourselves, or allocate them to such and such a space/time. Drifting, to be sure, but all dressed up.

1 Romy Golan, “Jannis Kounellis. Negev Museum of Art”, Artforum, March 2017.

2 Germano Celant, “Mario Merz : The Artist as Nomad”, Artforum, December 1979.

3 Beatriz Preciado, Testo Junkie. Sex, Drugs and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, Feminist Press, 2013.

4 Ibid, p.35.

(Image on top: Jeanne Briand, GameteGlass (black), 2016. Blown glass gamete with black pigment, harness made of hair and silicone stitched to hanging straps, painted steel fastenings, xlr cable, 170 × 70 × 17 cm. Photo : Romain Darnaud.)

- From the issue: 84

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Craft is Back, Art & Cultural Appropriation, TV Resists,

Related articles

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret