Dena Yago

Dena Yago: “The beauty of poetry is its inability to be instrumentalized”.

At the turn of the 2010s, something in the machinery of language got jammed. No need to be a linguist to notice it: among language’s usual functions1, we now had to contend with an entirely surplus part. This wasn’t really referential, not quite phatic, and truthfully not very expressive. No, language now also included a whole specialized and often immediately privatized idiom, composed of clever brand names, punchy slogans, convoluted legal terms, but also stammering lines of code and spam with limping humanity.

Dena Yago, born in 1988 and based in New York, is an artist. She is also a sculptor, critic, and above all perhaps a poet. In her work, everything brings forth constellations and compositions from the inanity of this same prefabricated language, which is nevertheless our only one and with which we must somehow compose. In her visual works, the readable word gives way to the visible word, which borrows its ubiquity from the modern city. The striking force of advertising transforms into a cryptic presence where materiality regains upper hand, through accumulations of rubbery letters or industrious felt cutouts, murals or large screens traversed by cartoonish figures. Another aspect of the artist’s practice is her role within the artist and trend-forecasting group K-HOLE (https://khole.net/), that she co-founded. From 2010 to 2016, five young art school graduates – besides the artist, Greg Fong, Sean Monahan, Chris Sherron and Emily Segal – published freely accessible PDF reports. These, composed of images and text, modelled their form on that which sells for gold in marketing agencies, attempting to analyze the surrounding reality – rather than simply offering critique aimed at the art world.

Finally, Dena Yago draws from these two relationships to language a third register, one that properly deals with surplus language, composed of the slag that doesn’t fit elsewhere. This concerns the truly poetic part of her practice, the one that has always accompanied her, and which, for her, precisely resists instrumentalization, commodification, and all forms of utilitarianism: poetry, a slightly dissonant poetry, discreetly arrhythmic, one that seeps from spaces almost without shadows or toiling bodies, composed of all this surplus. With us, the artist discusses her multiple relationships to language, solo or collective, as she prepares a new book with Viscose ( https://viscosejournal.com/ ) and, in spring 2016, an edition of her critical texts to be published by After 8 Books.

How did you decide to become an artist?

Dena Yago – I knew that I wanted to make art and be an artist from a very young age. When I started undergrad at Columbia, my thought at the time was that I would be an art major, which I did. I didn’t really have any context for what the art world or the art market was at that time. At Columbia, it was the time when Dana Schutz and a lot of artists were blowing up as market darlings; it was a period when the MFA program was getting artists being bought out of their studios for ridiculous sums of moneys. It was very much like a pre-recession boom cycle, so at 17 when I started school, I was very immediately made aware of what the market aspect of art as an industry were. It hadn’t really crossed my mind that I could sustain myself as an artist previous to going to college, so the notion of a career wasn’t necessarily the goal.

My first job in the artworld was at Peres Projects in Los Angeles, which was also very much a market darling of the moment. My first interaction with the artworld was working on projects for Dash and Agathe Snow over the summer; that was around the time when Terence Koh, Dan Colen, Dash and everybody were being hold up on a very high pedestal. At that point, art and the market around it became defined as something driven by a group of friends. There was a cover article that was very famous at the time with Ryan McGinley, Dan Colen and Dash Snow all in bed together [New York Magazine, January 15, 2007]. That was definitely my education: if one wanted to make meaning in the world, one had to do that in a networked way with their friends. Most of my peers were looking towards publishing as the goal. Everybody wanted to be literary agents, novelists, or work in magazines. In the span of four years, that industry completely bottomed out; we saw the complete decline of legacy media and publishing as a viable reer happen. The net that seemed to catch everybody instead was branding and marketing.

Did you already have a relationship to language as a student?

I was really only doing academic writing, and then I started to incorporate more prose poetry into my art practice. I was doing primarily photography, but I was also doing these sculptures where I would hang prose poems or booklets from the frame of a photograph. There was a relationship between the two, but I was not writing poetry till after I graduated.

You graduated in 2010, in the aftermath of the financial crisis with Occupy Wall that would happen one year later. What impact did the economic context have on your life as a young artist?

In Emily Segal’s book Mercury Retrograde (2021), my character is in the intro popping a Xanax outside of Wall Street before going in there. The other side of that lore was that the law firm that I worked at was on Zuccotti Park, so my relationship to that was the same critique that everyone had of Occupy; I don’t think I was seeing myself as a participant as much as an observer. We are still dealing with the ramifications of this, which is that it didn’t have any specific demands.

K-HOLE was born that same year, as the five of you had just graduated the same year from different universities. How did it all start?

Emily and I had met in Berlin in 2009 when we were still in college and we were both studying abroad. She was working on a literary magazine with Pablo Larios out there, and I was working for Rirkrit Tiravanija, studying with Josephine Pryde [at Universität der Künste] and making my own work. I was focussed on visual art whereas she was focussed on more of the literary scene, and then we both moved back to the United States to finish our studies. I met Greg Fong through another friend, Dan DeNorch. I met him in Miami; the first evening that we hung out was actually the premiere of Jersey Shore that same year. I feel like our shared view of pop culture was really recognized; we both were cut from the same cloth and analysing what was happening in the world in a similar way. At that time, Greg was an artist collaborating with Sean Monahan and Chris Sherron – they all went to Rhode Island School of Design. It was in the spring before I even graduated that we all decided to start K-HOLE. We put out our first report in the first year out of college, in 2011.

“K-HOLE #1: FragMOREtation: A Report on Visibility” borrowed the form and language of a commercial genre popular within the marketing work. Did you envision the art project as a way to earn money then?

It was absolutely not a commercial pursuit. I had been working for Ryan Trecartin in college, and he was actually the first person that exposed me to a trend report. He showed me a trend report called “Transumerism”, which was sort of an extension of Rem Koolhas’ “junkspace” and about the global travelling class. Reading that report, I found it so interesting; it was armchair sociology and the language that was used was really legible to a mass audience. It was everything that I was reading in my anthropology classes chopped full of emojis. It became very attractive for me as a vessel for cultural critique. We definitely started it as an art project. I remember having a conversation with Cab Broskoski [co-founder of Are.na]; at the same time that I was working on K-HOLE, I also was in the founding team of this website Are.na. I remember being asked if I would like to do K-HOLE if it made me money and being very taken aback by that. It seemed like such an unrealistic thing that I also didn’t think about it too much before it ended up being on the table.

K-HOLE embodied the position of blending in, as if it had fully integrated the “no outside” stance of Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri or Mark Fisher. Where were you standing in respect to legacy media or gatekeeping institutions?

It is funny because I feel that the language of legacy media or gatekeeping intuitions was not in my vocabulary pre-2016. A lot of the motivation for how we were approaching that stuff was out of real material need: graduating in the recession, feeling like the industry we had hoped to take part in was crumbling around us, seeing how creative work – especially language-based work – was being devalued. That is now what we talk about as “legacy media”. I don’t think that we ever felt entitled or promised a career in any of these things, but we were very much just trying to make our way; to see what a creative life would look like and how it could be sustained in the city that was our home, which was New York.

Why did it make sense for you to work as an artist group under a shared name?

Our line in the first few reports what that we were a group of cultural producers, all under 25 and living in downtown New York. This is an annoying way to self-describe, but we didn’t want to be ghettoized in world of everything being a performance, also because our relationship to institutional critique felt like the performance almost stood in the way of understanding the thing as an actual practice. We were trying to dial down the performativity of it, and that was a question that we would constantly get: Is this ironic? Is this a performance? We responded by saying that we were doing trend forecasting and defined what that was.

The models we were looking at were Bernadette Corporation, Art Club 2000 and General Idea. The collective voice was the most interesting life-lesson that I got out of K-HOLE; how much power comes from creating a collective voice and how much freedom comes from speaking truth to power within that context, versus all of us individually trying to lob cultural critique into the world. If you look at the reasons why we did K-HOLE and the material need at the time, I see the recession as a product of a hyper individualized society as well as a failure of the 1968 critiques. Anything collective feels uncommodifiable in that way, and that was the thing we were constantly told by institutions, that galleries don’t represent collectives and that collectors do not buy work from them either. Undermining ourselves in that way was not ever going to work out in the art market for sure.

K-HOLE was primarily writing-based. In the reports, there is a recognizable voice which treats ambient contemporary chatter as found footage. How do you deal with language in your production, in the group and in your own practice?

I personally am also very interested in group dynamics and what gets produced between people, especially within this very human context of deep friendship. That is where we were starting from; we would also always talk about ourselves as five friends. The language that emerged out of that was truly a collective voice that was not over-architected; it came out of the process of us round-robin and editing each other’s writing until we generated a tone that felt very powerful and larger than any of us individually. That is what we carried through as something that we each felt equal authorship of. When I think about what K-HOLE was in its most pure form, it was that voice. A lot of our friends at that time were experimenting in similar forms of collectivity, such as Max [Pitegoff] and Calla [Henkel], Bruce High Quality Foundation, Jogging –which is more image-based — and DIS definitely.

In my own practice, I have three different threads of writing. One is poetry, one is long-form cultural criticism, and then the other is more concrete poetics entangled in visual forms – which is my art. Then there is corporate brand writing with quite formal constraints, such as the writing that I was doing for Are.na, or for work with clients, where language had to be operationalized. In the process of that, there was always a part of excess language that doesn’t really fit anywhere, and that is what fuels the poetry in a lot of ways. This is why so much of the poetry I am writing is done in the context of other works. This is truly the beauty or the value of poetry: its inability to be instrumentalized, commodified, or capitalized on. It is very important to me to maintain that, because I really believe in poetry. I got into poetry because when I graduated, I couldn’t afford a studio, and it was the way I could sketch out my relationship to the world through language. Essays are closer extension of the K-HOLE world, and then the writing as a visual practice is thinking about the materiality of language that can only exist in the relation between images and objects.

You almost always associate words with images. This was for instance the case in Fade the Lure (2019), your fourth book of poetry published by After 8 Books. What does such a combination produce?

I am very interested how to have a relationship between text and image that is more than juxtaposition, captioning, illustration but that. Also, in my more cartoonish work that have a kind of comic book poetry attached to it, I try to expand the world of language by creating an affect. This open relationship to these things is what art can really provide, where it becomes more of a space of contemplation as opposed to one singular form.

What are you currently working on?

I spent the last five years honing in on this way of image-making, the printed on canvas, dyed paintings with text. Last year, I had a kid, and it felt like a fundamental break in how I relate to materials and images. So, I am only starting to get back to the practice, but now all of that I am making are so tied to a text I am working on. I am writing a book with [art critic] Jeppe Ugelvig, he is starting to publish books through Viscose, and it is about motherhood and supply logistics accompanied by photographs that I am making. Then, there is also a book for After 8’s collection of artists’ writings [planned for spring 2026]. It is taking all the texts that I have written since 2016, the year that K-HOLE ended, and when I wrote “Empire Poetry”2 with a few other new ones.

(1) Selon le linguiste Roman Jakobson, le langage se décompose en six fonctions de communication : référentielle, expressive, poétique, conative, phatique et métalinguistique.

(2) Yago, Dena. « Dena Yago. Empire Poetry ». Texte Zur Kunst – « Poetry », no No. 103 (2016): 146261.

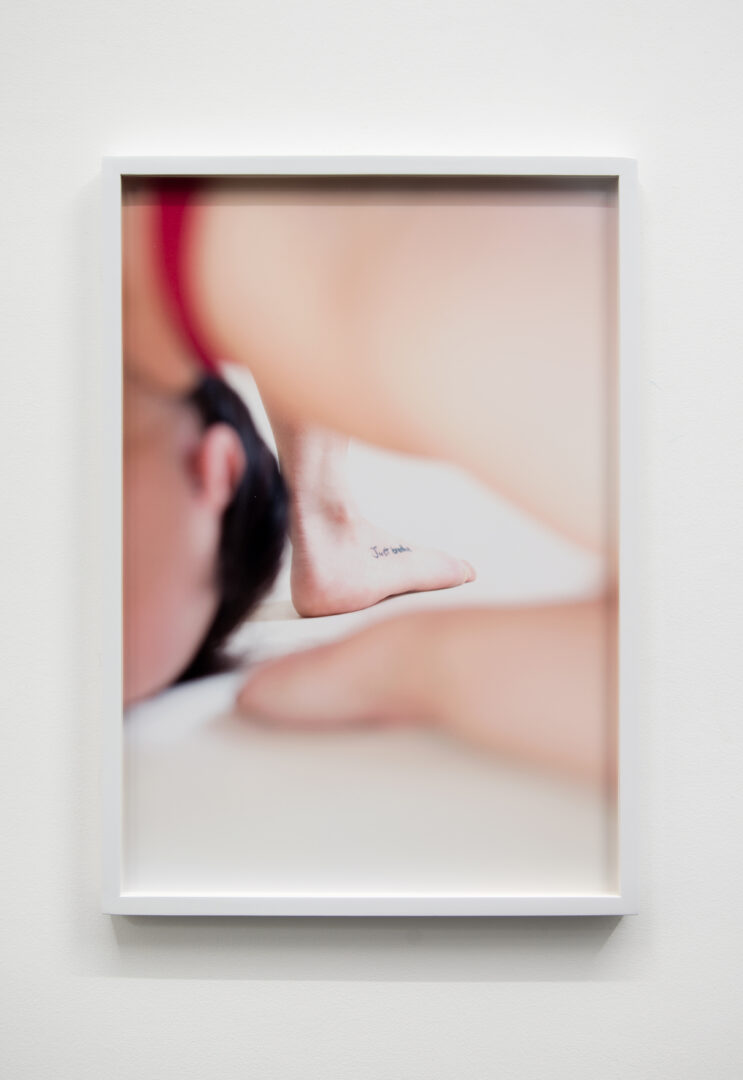

Head image : Exhibition view : Dena Yago, « Force Majeure », 2019, High Art, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and High Art, Paris / Arles.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff, Geert Lovink : “Not a single generation stood up against Zuckerberg” , Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion, Hoël Duret, CLEARING,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Clémence Agnez

Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Geert Lovink : “Not a single generation stood up against Zuckerberg”

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad