Entretien avec Frédéric Bonnet et Eric Mangion

Dans le flux de la peinture

Propos recueillis par Pierre Tillet

Pierre Tillet. Quinze ans après celle du Centre Pompidou, quels sont les objectifs de la rétrospective consacrée à Gérard Gasiorowski (1930-1986) au Carré d’art de Nîmes, dont vous êtes les commissaires ?

Frédéric Bonnet. L’un des buts de cette nouvelle rétrospective est de redonner à voir ce qui a été beaucoup oublié. Il y a une génération qui a côtoyé Gasiorowski et connaît son œuvre. Quant aux jeunes historiens d’art et aux jeunes critiques, ils ont une vision lacunaire de son travail. Comme il n’y a pas eu d’exposition marquante de Gasiorowski depuis celle du Centre Pompidou en 1995, à l’exception de celle organisée par Éric Mangion à la Villa Arson qui était focalisée sur Kiga et sur l’Académie Worosis Kiga (1), il nous a semblé important de revenir sur ce travail et d’en présenter une nouvelle lecture, qui ne soit pas chronologique stricto sensu, ce qui a déjà été très bien fait.

Y a-t-il une cohérence dans cette œuvre, connue pour ses revirements, ses travestissements, que vous souhaitez montrer sous un nouveau jour ?

Éric Mangion. L’œuvre de Gasiorowski est faite de recommencements et de questionnements permanents. On ne peut pas vraiment parler de revirements, mais plutôt d’une mise en abyme de son travail. Néanmoins, il y a une cohérence d’ensemble qui passe par une quête du sens et de l’origine de la peinture. Pour lui, cette dernière était un tout qu’il appelait la « ligne indéfinie ».

Peut-on comprendre l’itinéraire de Gasiorowski à partir de l’idée d’« attitude » ?

FB. Je n’en suis pas sûr. Le terme « attitude » évoque l’idée de rôle, or Gasiorowski ne joue pas un rôle, même quand il se travestit en Indien et qu’il fait des performances dans son atelier. Je crois qu’il faut plutôt partir de son obsession liée à la question : « Puis-je être peintre ? » A cette interrogation fondamentale, il apporte des réponses plastiques dont il ne se satisfait jamais. Il a besoin de les dépasser en permanence. C’est le sens du titre de l’exposition, Recommencer. Commencer de nouveau la peinture, qui reprend des phrases tracées de la main de Gasiorowski au dos d’un tableau. C’est une clé de compréhension nécessaire pour aborder l’œuvre de Gasiorowski. Il ne s’agit pas d’attitude, mais d’une volonté de comprendre la peinture.

On a souvent comparé son itinéraire avec ceux de Malcolm Morley, Philip Guston, ou Gerhard Richter. Qu’en pensez-vous ?

FB. On trouve chez ces artistes la même interrogation : « Puis-je faire un bon tableau ? » Au moment où il est au sommet de son art, dans la période hyperréaliste, Gasiorowski arrive à une excellence telle qu’il lui faut « miter » le tableau, dit-il lui-même. C’est à ce moment qu’il passe aux Croûtes, des tableaux régressifs, tartinés, mais dont les qualités plastiques sont évidentes.

Œuvres kitsch, brutales et colorées, les Croûtes représentent pour Gasiorowski, selon ses propres termes, « la première intervention de la peinture » (2). Nous savons pourtant que L’Approche (1965-1970), cette série en noir et blanc, exécutée d’après photographies, fait déjà partie de la peinture. Elle n’en est pas que le préambule…

EM. Ce qui agace Gasiorowski dans L’Approche, c’est le systématisme de la représentation. Pour lui, ce n’est pas réellement de la peinture, mais de la fabrication d’images. Il ne faut pas oublier qu’il était, à l’époque des Approches, archiviste chez Delpire, la plus grande agence de photographie en France où il manipulait des images quotidiennement. Pour lui, la peinture n’est pas une question d’image. C’est une pratique expérimentale qui passe d’abord par le faire. Avec les Croûtes, il met la main dans le cambouis.

FB. Les images photoréalistes chez Gasiorowski ne sont jamais des copies pures et simples de photographies. Il les recadre systématiquement, il fait un focus sur ce qui l’intéresse le plus dans le motif.

Peut-on considérer Gasiorowski comme un « classique » de l’art contemporain ? Selon Bernard Marcadé, il n’était pas de son temps et échappait « aux misérables enjeux de notre pauvre postmodernité artistique » (3).

FB. Je pense qu’on peut le considérer comme un artiste classique dans cette volonté d’être peintre. Par contre sa manière d’aborder la peinture est très ambivalente. La peinture n’est pas une, mais plusieurs choses, et dans sa quête, Gasiorowski a élaboré une machine de guerre. Si l’on extrapole, sa trajectoire est semblable à un programme informatique qui essaye toutes les combinaisons possibles pour atteindre son but, avec, bien sûr, les failles de l’humain.

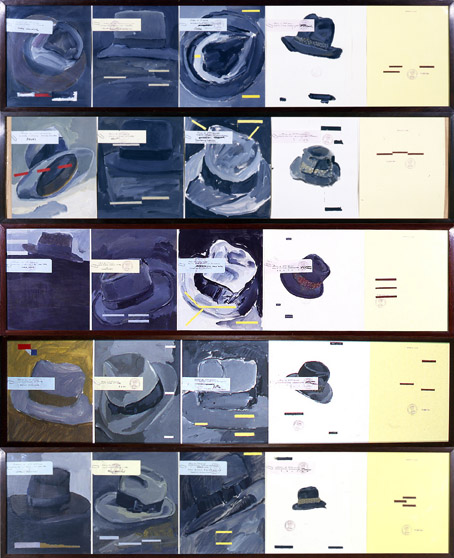

EM. C’est quelqu’un qui luttait contre tous les académismes, qu’ils soient classiques ou modernes. Il a lui-même créé une académie fictive, intitulée Worosis Kiga (l’anagramme de son nom, 1975-1982 – ndr), dirigée par le professeur Arne Hammer. Ce personnage enseignait la représentation d’un chapeau, traité de manière conceptuelle. On pourrait le considérer comme un professeur des années 1970, parce que sa pratique est processuelle et sérielle. En même temps, quand on le voit représenté par Gasiorowski, le professeur Hammer apparaît comme quelqu’un qui se prend pour Cézanne, est habillé comme lui, marche comme lui dans la montagne. Il y a là beaucoup d’ironie.

Que pensez-vous de la célèbre déclaration de Gasiorowski dans laquelle il présente son lien avec la peinture comme « la relation la plus étroite, une aventure d’ordre quasiment sexuel et très intense, l’orgasme partagé, exceptionnel et dans les positions les plus variées » (4) ?

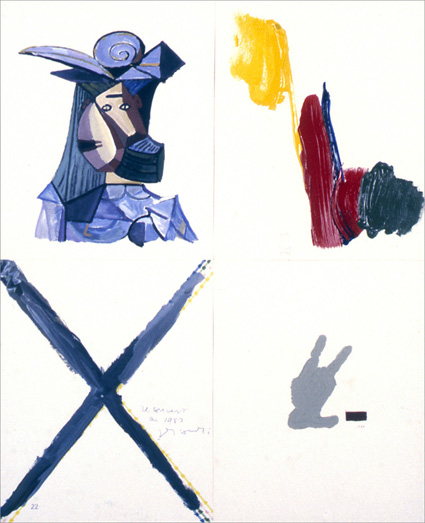

Gérard Gasiorowski, Académie Worosis Kiga, Les Classes, 1975-1980, acrylique on paper, 36 x 160 cm chaque/each

EM. Cette phrase est à prendre avec détachement car Gasiorowski n’était pas que cela. Il y avait évidemment une dimension organique dans son travail. Mais il faut aussi considérer la dimension réflexive qui est corollaire au vitalisme de l’œuvre. La meilleure illustration de cette ambivalence constante chez lui est Kiga. Cette dernière est conçue comme une divinité qui incarne la Peinture. Il quitte alors le tableau, l’espace pictural pour réaliser des rites poétiques dont il ne reste que des objets/reliques : des pots et des bâtons de couleurs, des morceaux de tissus, des bijoux, des vêtements, des parures diverses… Pour lui, il ne s’agit pas d’une action détachée du reste de l’œuvre. Kiga s’inscrit dans un programme qui commence avec L’Approche et qui consiste à interroger la peinture par tous les moyens.

Quelle est l’importance de la fiction dans l’œuvre de Gasiorowski ?

FB. Les fictions qui se croisent parfois, s’imbriquent, représentent un outil permettant à Gasiorowski de rebondir lorsqu’il a épuisé telle ou telle exploration. Une fois qu’il a clos un chapitre, il invente une nouvelle fiction. C’est d’abord l’Académie Worosis Kiga, puis Kiga et enfin Les Paysans, qui sont des cadres dans lesquels rentre le travail. Pour revenir sur Worosis Kiga, il détestait tellement les académismes qu’il en a fait un chapitre complet de son œuvre pour montrer à quel point tout cela ne fait qu’entretenir une illusion de la peinture. Ce chapitre se referme quand le directeur de l’Académie, le professeur Hammer, est tué par Kiga, qui représente la pureté de la peinture et un nouveau recommencement.

À la fin des années 1970, qu’est-ce qui a amené Gasiorowski-Kiga à utiliser ses matières fécales mélangées à des végétaux comme matériau ou médium pictural dans les Tourtes (1977-1979) ou les Jus (1977-1979) ?

FB. Pour peindre, Gasiorowski n’a plus besoin de pinceau, de pigments. Il lui suffit de se servir de la matière – sa merde mélangée à de l’herbe – et de ses doigts. C’est une manière pour lui de revenir au fondement de l’acte pictural, en s’étant débarrassé de toutes les scories qui peuvent polluer le tableau.

Quel est le rôle de la série chez Gasiorowski ?

FB. Pour en comprendre la logique, il faut en revenir à l’idée d’épuisement. Gasiorowski travaille à partir d’une idée et quand elle est épuisée, formellement ou intellectuellement, il arrête. La série est particulièrement importante, parce qu’elle permet un empilement par strates, un recouvrement, un recommencement. Quand une série est achevée, elle est recouverte par une autre et l’œuvre se développe de cette manière.

Il y a une inactualité de l’œuvre de Gasiorowski, comme si elle s’inscrivait dans le flux de la Peinture qui débute avec Lascaux et se continue avec Richter, en passant par Rembrandt, Manet…

FB. Justement, nous montrons dans l’une des dernières salles de l’exposition une œuvre de plus de vingt mètres de long, composée de douze panneaux, qui s’intitule Fertilité (1986) et qui est un véritable flux pictural.

EM. Lorsqu’il expose à l’ARC en 1983, Gasiorowski prend en charge l’accrochage et présente ses œuvres de façon très linéaire. Le public et ses proches, qui avaient l’habitude d’un peintre de conflits, de contradictions, de recommencements, de recouvrements, sont déconcertés. Au même moment, pour le centième anniversaire de la mort de Manet, il présente au Centre Georges Pompidou un tableau de dix mètres de long consistant en une seule ligne en référence à l’asperge isolée de Manet. Michel Enrici, qui est un de ses proches, comprend alors que Gasiorowski a une vision holiste de la peinture : elle est un tout, un flux dans lequel il s’inscrit comme tous les artistes qui l’ont précédé ou qui vont le suivre.

(1) Exposition « Gérard Gasiorowski », Villa Arson, Nice, 2007. Simultanément se déroulaient trois expositions autonomes, consacrées à Gino de Dominicis, Saverio Lucariello, Julien Bouillon.(2) « Gérard Gasiorowski, entretien avec Bernard Lamarche-Vadel (1975) », in Nicole Gersen, « Biographie », in Gérard Gasiorowski, cat. exp., Paris, Centre Pompidou, 1995, © Galerie Maeght, Paris, 1995, © Spadem, Paris, 1995, p. 229.(3) Bernard Marcadé, « Gasiorowski : l’inactuel, le saboteur et l’insolent », in Gérard Gasiorowski, op. cit., p. 28.(4) Propos de l’artiste in Jean de Loisy, « C’est à vous, Monsieur Gasiorowski », in Gérard Gasiorowski, op. cit, p. 12.Gérard Gasiorowski, Recommencer.

Commencer de nouveau la peinture

Carré d’art, Musée d’art contemporain de Nîmes

19 mai – 19 septembre 2010

Commissariat Frédéric Bonnet et Éric Mangion

A paraître aux éditions Hatje/Cantz, catalogue bilingue français/anglais, textes de Frédéric Bonnet, Éric Mangion, Laurent Manœuvre, Erik Verhagen, et entretien inédit avec Thomas West, réalisé peu avant la disparition de l’artiste. 192 pages, environ 200 documents, 23 x 28 cm.

In the Ebb and Flow of Painting

Interview with Frédéric Bonnet and Eric Mangion,

curators of the Gérard Gasiorowski retrospective at the Carré d’Art, Musée d’art contemporain, in Nîmes, by Pierre Tillet.

Pierre Tillet Fifteen years after the Centre Pompidou show, what are the aims of the Gérard Gasiorowski (1930-1986) retrospective at the Carré d’Art in Nîmes, which you are curating?

Frédéric Bonnet One of the aims of this new retrospective is to re-present things that have been greatly forgotten. There’s a generation that rubbed shoulders with Gasiorowski and knows his work. As far as young art historians and young art critics are concerned, they have a patchy vision of his oeuvre. Because there hasn’t been any outstanding Gasiorowski show since the one held at the Centre Pompidou in 1995, apart from the one organized by Eric Mangion at the Villa Arson in Nice, which focused on Kiga and the Worosis Kiga Academy1, it seemed important to us to come back to this work and offer a new reading of it, one that is not chronological, strictly speaking, because that has already been very well done.

PT Is there a coherence in this oeuvre–which is well-known for its sudden about-faces and its disguises—which you want to show in a new light?

Eric Mangion Gasiorowski’s oeuvre is made up of recommencements and ongoing challenges. You can’t really talk of about-faces, but rather of an endless duplication—a mise en abyme—in his work. But there is an overall coherence which proceeds by way of a quest for the meaning and origin of painting. For him, this latter was a whole which he called the “undefined line”.

PT Can we understand Gasiorowski’s itinerary based on the idea of “attitude”?

FB I’m not sure. The word “attitude” conjures up the idea of roles, but Gasiorowski didn’t play any role, even when he dressed up as an Indian and put on performances in his studio. I think it’s probably better to start with his obsession associated with the question: “Can I be a painter?” To this basic question he offered visual responses which he was never satisfied with. He needed to be going beyond them all the time. This is the sense of the exhibition’s title, “Recommencing. Starting painting again”, which borrows words drawn by Gasiorowski’s hand on the back of a picture. This is a vital key to understanding how to broach Gasiorowski’s oeuvre. It’s not a matter of attitude, but rather of a desire to understand painting.

PT People have often compared his career with the careers of Malcolm Morley, Philip Guston, and Gerhard Richter. What do you think about that?

FB You find with these artists the same question: “Can I make a good picture?” Just when he was at the height of his art, in the hyperrealist period, Gasiorowski achiecvd such excellence that he had to “miter” the picture, to use his own word—he had to make it look “moth-eaten”. It was at that moment that he shifted to the Croûtes/Bad Paintings, regressive, churned-out pictures, but with obvious visual qualities.

PT The Bad Paintings, which are kitsch, brutal and colourful , represented for Gasiorowski, to use his own words, “the first intervention of painting”2. But we know that L’Approche/The Approach (1965-1970), that black and white series, made from photographs, was already part of the painting. It was just the preamble…

EM What bugs Gasiorowski in The Approach is the systematicness of the representation. For him, it’s not really painting, but the manufacture of images. We shouldn’t forget that, at the time of The Approaches, he was an archivist at Delpire, France’s biggest photographic agency, where we was handling images day in day out. For him, painting was not a matter of imagery. It was an experimental activity that involved making, first and foremost. With the Bad Paintings, he got his hands dirty.

FB Photo-realist images with Gasiorowski were never copies of photographs, pure and simple. He systematically reframed them. He focused on what interested him most in the motif.

PT Can we regard Gasiorowski as a contemporary art “classic”? According to Bernard Marcadé, he did not belong to his day and age, and he dodged “the wretched challenges of our poor artistic postmodernity”3.

FB I think we can regard him as a classic artist in his desire to be a painter. On the other hand, his way of broaching painting was very ambivalent. Painting was not one thing, but several, and in his search, Gasiorowski developed a war machine. If we extrapolate, his career was like a computer programme that tries out every possible combination to achieve its goal, with, needless to add, human flaws.

EM He was someone who fought against every manner of academicism, classical and modern alike. He himself created a fictitious academy called Worosis Kiga (an anagram of his name, 1975-1982 – Ed.), run by professor Arne Hammer. This person taught how to depict a hat, dealt with conceptually. He might be regarded like a 1970s’ teacher, because the way he taught was process-related and serial. At the same time, when you see him depicted by Gasiorowski, professor Hammer looks like someone taking himself for Cézanne, dressed like him, and walking like him in the mountains. There’s plenty of irony there.

PT What do you think about Gasiorowski’s famous declaration where he introduces his link with painting as “the closest relation, an almost sexual and highly intense adventure, with incredible shared orgasms, and in the most varied of positions”4.

EM Those words should be taken in a detached way because that’s not how it was with Gasiorowski. Obviously enough, there’s an organic dimension in his work. But we should also consider the reflective dimension which is the corollary to the vital nature of his oeuvre. The best illustration of this ongoing ambivalence with him is Kiga. This latter is conceived like a deity incarnating Painting. So he quit the picture and the pictorial space, and undertook poetic rites, from which only objects and relics remain: pots and coloured rods, scraps of fabric, jewels, clothes, various finery… For him, what was involved wasn’t an action separate from the rest of the oeuvre. Kiga was part and parcel of a programme that started with The Approach and which consisted in questioning painting in every possible way.

PT What’s the importance of fiction in Gasiorowski’s work?

FB Fictions which sometimes intersect, and are dovetailed, represent a tool enabling Gasiorowski to bounce back when he had exhausted such and such an avenue of exploration. Once he’d closed a chapter, he invented a new fiction. First it was the Worosis Kiga Academy, then Kiga, and lastly Les Paysans/The Peasants, which were frames which the work fitted into. Getting back to Worosis Kiga, he had such hatred for all forms of academicism that he came up with a whole chapter about this in his oeuvre, to show the degree to which all that merely entertained an illusion of painting. That chapter was closed when the Academy’s director, professor Hammer, was killed by Kiga, representing the purity of painting and a new beginning.

PT In the late 1970s, what was it that led Gasiorowski-Kiga to use his own faeces mixed with plants as a pictorial matter and medium in the Pies (1977-1979) and the Juices (1977-1979)?

FB To paint, Gasiorowski didn’t need brushes and pigments. He merely had to use matter—his shit mixed with grass—and his fingers. It was a way for him of getting back to the foundations of the pictorial act, by having got rid of all the dross that can pollute the picture.

PT What role did the series play in Gasiorowski’s work?

FB To understand the logic of it, we must go back to the idea of exhaustion and depletion. Gasiorowski worked from an idea, and when it was exhausted, formally and/or intellectually, he stopped. The series was especially important because it permitted an accumulation of layers, a covering, a recommencement. When a series was completed, it was covered by another one, and the work developed like that.

PT There’s something out-of-date about Gasiorowski’s work, as if it were part of the ebb and flow of Painting, that starts with Lascaux and carries on up to Richter, by way of Rembrandt and Manet…

FB Quite. In one of the last rooms in the exhibition, we show a work that’s more than 23 metres/75 feet long, made up of twelve panels, titled Fertility (1986), which is nothing less than a pictorial ebb-and-flow.

EM When he exhibited at the ARC, in Paris, in 1983, Gasiorowski took charge of the hanging, and presented his works in a very linear way. The public, and people close to him, who were used to a painter of conflicts, contradictions, recommencements, coverings-up, were disconcerted. At the same time, for the 100th anniversary of Manet’s death, he showed at the Centre Georges Pompidou a picture that was 10 metres/35 feet long consisting in a single line referring to Manet’s solitary asparagus. Michel Enrici, one of his close friends, then realized that Gasiorowski had a holistic vision of painting: it is a whole, an ebb-and-flow in which he includes himself like all the artists who have gone before him, and will come after him.

(1) Exposition “Gérard Gasiorowski”, Villa Arson, Nice, 2007. Three exhibitions were held simultaneously, devoted to Gino de Dominicis, Saverio Lucariello, and Julien Bouillon.(2) “Gérard Gasiorowski, entretien avec Bernard Lamarche-Vadel (1975)”, in Nicole Gersen, “Biographie”, in Gérard Gasiorowski, exh.cat., Paris, Centre Pompidou, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1995, © Galerie Maeght, Paris, 1995, © Spadem, Paris, 1995, p. 229.(3) Bernard Marcadé, “Gasiorowski : l’inactuel, le saboteur et l’insolent”, in Gérard Gasiorowski, op. cit., p. 28.(4) The artist talking in Jean de Loisy, “C’est à vous, Monsieur Gasiorowski”, in Gérard Gasiorowski, op. cit, p. 12.« Gérard Gasiorowski. Recommencer. Commencer de nouveau la peinture », at the Carré d’Art, Musée d’Art contemporain de Nîmes, from 19 May to 19 September. A bilingual, French/English catalogue will be published by Hatje/Cantz, with essays by Frédéric Bonnet, Éric Mangion, Laurent Manœuvre, and Erik Verhagen, as well as a hitherto unpublished interview with Thomas West, conducted shortly before the (1) Exposition « Gérard Gasiorowski », Villa Arson, Nice, 2007. Simultanément se déroulaient trois expositions autonomes, consacrées à Gino de Dominicis, Saverio Lucariello, Julien Bouillon.(2) « Gérard Gasiorowski, entretien avec Bernard Lamarche-Vadel (1975) », in Nicole Gersen, « Biographie », in Gérard Gasiorowski, cat. d’expo., Paris, Centre Pompidou, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1995, © Galerie Maeght, Paris, 1995, © Spadem, Paris, 1995, p. 229.(3) Bernard Marcadé, « Gasiorowski : l’inactuel, le saboteur et l’insolent », in Gérard Gasiorowski, op. cit., p. 28.(4) Propos de l’artiste in Jean de Loisy, « C’est à vous, Monsieur Gasiorowski », in Gérard Gasiorowski, op. cit, p. 12.« Gérard Gasiorowski. Recommencer. Commencer de nouveau la peinture », au Carré d’Art, Musée d’Art contemporain de Nîmes, du 19 mai au 19 septembre. Un catalogue bilingue français/anglais sera publié aux éditions Hatje/Cantz, avec des textes de Frédéric Bonnet, Éric Mangion, Laurent Manœuvre, Erik Verhagen, ainsi qu’un entretien inédit avec Thomas West, réalisé peu avant la disparition de l’artiste. 192 pages, environ 200 documents, 23 x 28 cm.

artist’s death. 192 pages, approx. 200 documents, 23 x 28 cm.

articles liés

Céline Ghisleri

par Juliette Belleret

Claire Staebler

par Patrice Joly

Arnaud Dezoteux

par Clémence Agnez