Yannick Ganseman*

M Leuven, Leuven, 29.07-29.08.2021

Over the past year and a half, everyone was forced to stay at home, to refocus on their interior, the only connections to the outside world– besides few intermittent outings– being the various real and virtual windows that pierce the walls of homes. Artists did not escape this, the lucky ones being able to lock themselves up in their studios. Now that exhibitions are taking place again, the works produced during this period are coming out and being shown so that we can see the impact of the various lockdowns on artistic production. How does this strange period we have experienced manifest itself in artworks?

Yannick Ganseman’s recent pictorial work presents and considers this subject.1 Having been invited for a residency at M Leuven, confirmed, rescheduled, and finally organised, the artist (from Brussels) was able to move from his studio to another one, giving rise to an experimentation on memory painting. In a way that could seem a priori paradoxical, he began painting what he saw outside his windows in Brussels in the studio of his residency in Leuven. He typically works from photographs as many contemporary painters do. Yet, in this case, he based his work on drawings of the subject, from which he then painted in a (relative) geographical distance. This simple distancing plunged him back into questions that have marked the history of painting, as if the exceptional conditions of the pandemic and its small medieval connotation had relativized the weight of the past for him. “The Middle Ages for the Middle Ages, let’s dive into a dialogue with paintings on wooden panels of churches, the use of gold that gives absolute value and the windows open on the world of the Tuscan pioneers of the Quattrocento,” he seems to have said to himself. Not that the works are backward-looking, quite the contrary: they bring back what was singular in the past while reinterpreting it. Here, the representations are abstract, blurred and even voluntarily imperfect, botched– errors are not camouflaged. In the paintings, the artist reveals the process having led to its result. He mainly insists on the impasto in which the colour is taken: not touches of paint “à la van Gogh” but rather thick layers of plaster or ceramic that gives relief to the painting. This way of working is what frees the artist from the heavy tradition of oil painting, so he states. These layers give the paintings an air of Franz West’s “Passtuck,” one might add.

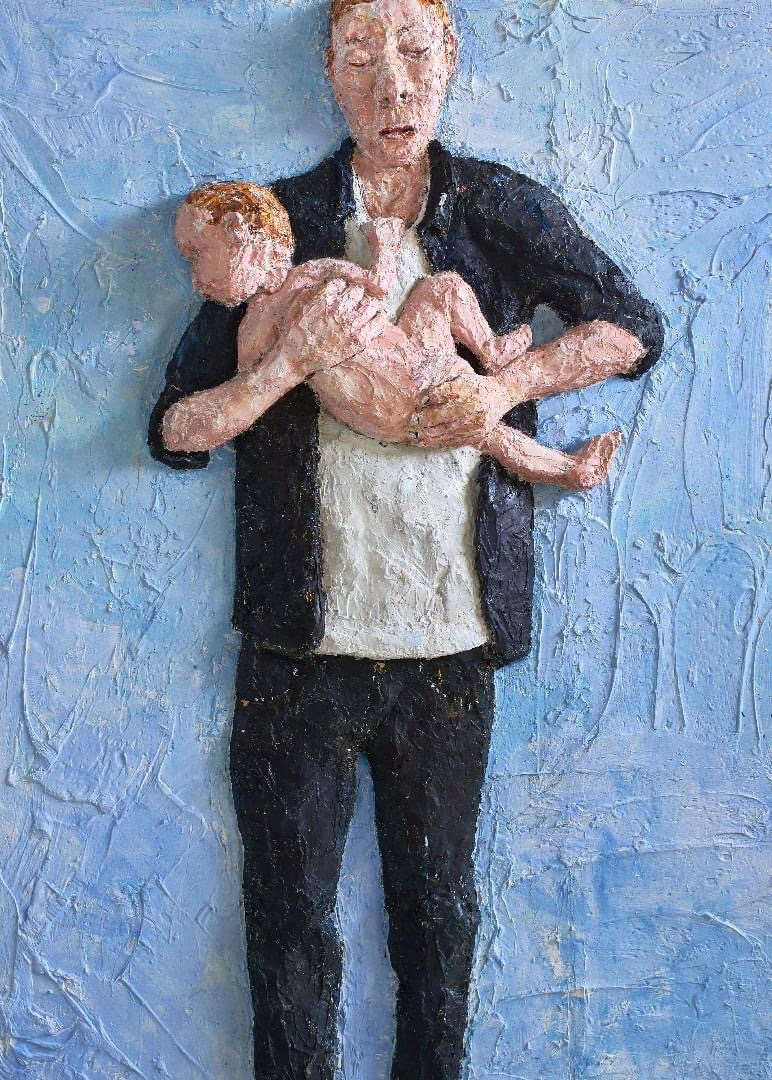

mousse PU et cadre en bois/Sculpture, oil painting on plaster mounted on PU foam and wooden frame,175x250x15 cm. Photo : Matthijs Van Der Burgt/Steven Decroos

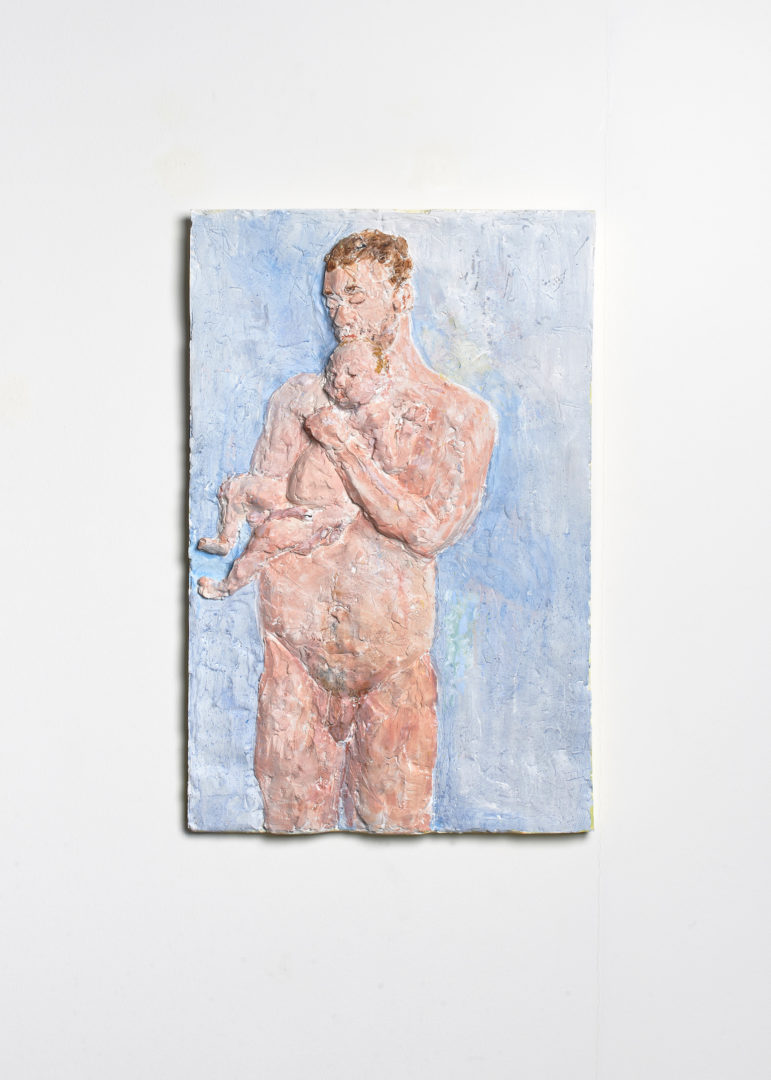

Two works, however, stand out: one small and one very large, both treating the same subject. The smaller one is hung on the wall amongst the other paintings, while the larger one is installed like a monument in the centre of the exhibition space. They depict neither landscapes, nor flowers, nor roofs, nor skies. They are self-portraits. Nothing extraordinary thus far. It is understandable that during lockdown artists found themselves facing themselves. Except that these two self-portraits are paternities. The term is so surprising that it is hardly understandable. To describe it in an academic way, the motif is that of the mother with child, soft and loving, holding her baby carefully in her arms. But the parent to the child in these two works is a father, a father to the child, who cares for the offspring, in an exchange of roles. The period having also corresponded to the birth of his daughter, the artist represented himself in this way. In the small painting he is naked; in the large one, he is in a suit, both on a blue background. The impasto and colours of these two canvases recall certain characteristics of Flemish painting, notably that of James Ensor, yet their iconography happily places them at the heart of current social issues, leading us to interpret them, in a sense, as the paintings of a feminist man.

*This text was written after an informal discussion with the artist in the exhibition. I would like to warmly thank him for his generosity.

- I describe these works first by the rather broad terms of “pictorial work” because his paintings are not quite in the form of paintings; or rather they are paintings so thick that they resemble painted bas-reliefs where the material is just as important as the color, I will get back to his.

Image on top : Yannick Gansema, Vue, 2021. Bas-relief, peinture à l’huile sur plâtre monté sur mousse PU et cadre en bois/Bas-relief, oil painting on plaster mounted on PU foam and wooden frame, 140x100x14 cm, Photo : Steven Decroos

- From the issue: 98

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Alias at M Museum, Leuven, Jérôme Zonder at Casino Luxembourg, Nathaniel Mellors, ELNINO76, Théo-Mario Coppola,

Related articles

Streaming from our eyes

by Gabriela Anco

Don’t Take It Too Seriously

by Patrice Joly

Déborah Bron & Camille Sevez

by Gabriela Anco