Images

Fridericianum, Kassel, from January 31 to May 1st 2016

Considering the loss of their monopoly on images, artists could well be feeling hostile to the rather mundane forms that have surfaced next to and increasingly independent from them. After all, aesthetics and scrutinising pictorial conditions do not seem to matter anymore in light of an apparently pointless snapshot and -chat culture, as well as in science, which finds knowledge in and throughout images. However, while researchers in the field of visual studies have developed their own ideas and theories for decades, artists have not shared their observations as much. That is not to say that they haven’t been keeping a wary eye all along, as a group exhibition at Kassel’s Fridericianum tries to prove.

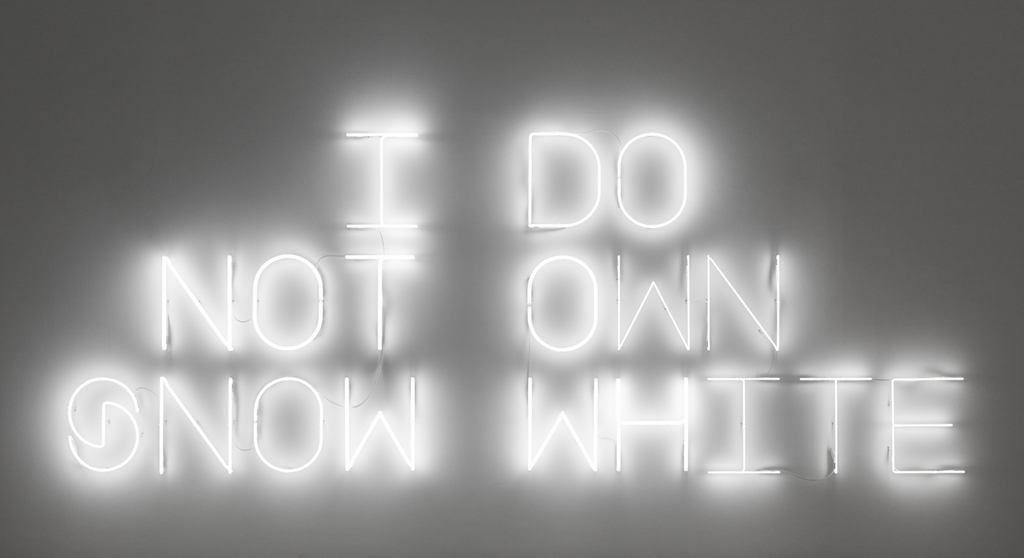

“Images” opens its long trail through the “realm of the imaginary”, a fairly beaten path lined with already iconic works, with two pieces by Pierre Huyghe. While the eponymous neon installation I Do Not Own Snow White (2005) bluntly points at the ownership of depictions of imaginary figures such as fairy tales, the following video installation Two Minutes Out Of Time (2000) lets a manga character speak for itself. Huyghe and Philippe Parreno found the computer animated girl alongside many others of her kind in a Japanese product catalogue and purchased the rights in order to set her free from all of her contractual and imaginary duties. Annlee, a frequent guest in French exhibitions, a petite pixel persona with large, hollow almond-shaped eyes, waving purple hair, and the overall featureless appearance of a cheap turn-of-the-century 3D modeling technology soon began to develop a consciousness of her own. She addresses the audience with considerations on her existence as a visual stand-in for an idea that emerged from a commercial context, to confront not only the viewer, but also herself, with the realisation that she is nothing but an empty shell. Still capable of imagination, the imaginary takes a step out of the shadow of intention and dependency, just to vanish, transcend itself and be reborn with the restart of the video.

Pierre Huyghe, I Do Not Own Snow White, 2005. Neon tubes, 185 × 487 cm. Photo : Nicolas Wefers. Courtesy Pierre Huyghe; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Thus, Annlee sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition: Parreno’s The Writer (2007) follows Pierre Jaquet-Droz’ famous automaton, an intricate piece of 18th century craftsmanship able to write up to forty characters of a given text. The wooden scrivener was tasked to spell a paradoxical question, only to stop a few letters short: “What do you believe your eyes or my wor…”?

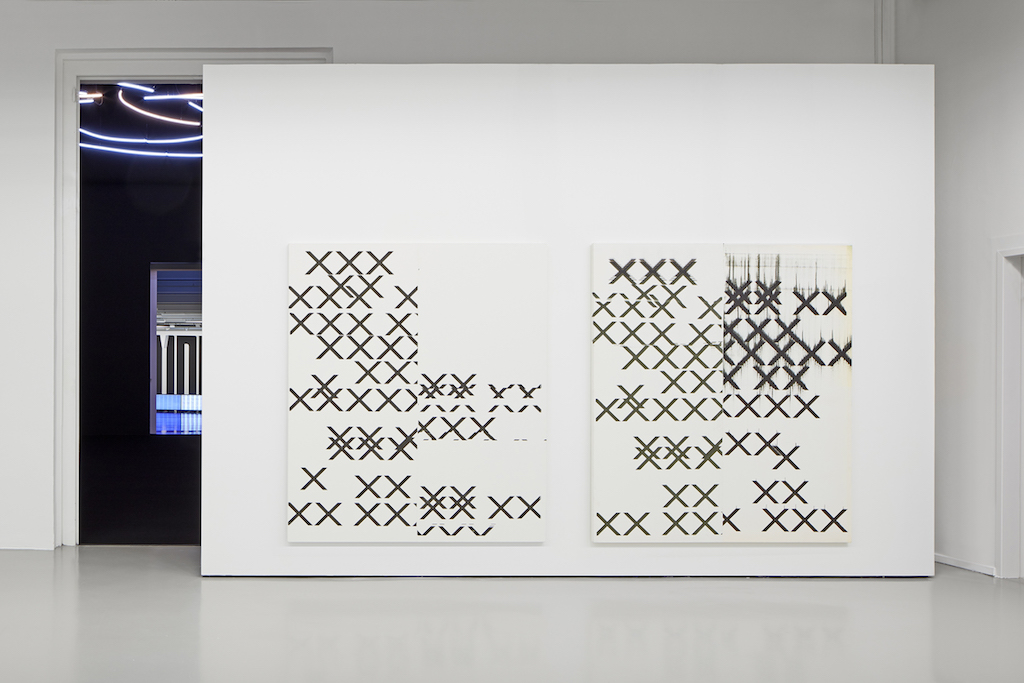

In yet another attempt to delegate autonomy to images bound to vanish, Cory Arcangel collected a day’s worth of neglected information stored in the RAM (Random Access Memory) of his computer: his Data Diaries (2003) on the upper floor trace back bits and pieces of code that were never meant to become visible, revealing their imaginary potential in a set of video pieces that, ultimately, fail to uncover the unseen as they spill a gibberish of glitch and data globs. Similarly, Wade Guyton’s untitled inkjet variations on the letter X (2006-2008) along with the streaks and smears of stuttering hardware employ the technical malfunction as an artistic gesture.

Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2006 (left) Epson UltraChrome inkjet on canvas, 203 × 175 cm. Courtesy of Haubrok Collection, Berlin. Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2006 (right), Epson UltraChrome inkjet on canvas, 203 × 175 cm. Private Collection, Berlin. Installation view Fridericianum. Photo : Nicolas Wefers.

However, in an effort of diversification, Susanne Pfeffer’s exhibition loses this promising track of disenchanting popular imagery from there on. Seth Price’s take on jihadist propaganda footage (Hostage Video Still With Time Stamp, 2005-2008) might emphasize its influence on our collective memory, but its lack of critique – of content, medium, and style – holds the principles and mechanics of this peculiar genre in suspense. Mark Leckey’s thorough examination of Felix the Cat, the first object broadcasted on US-American television is worth an appraisal of its own, yet seems out of place among the other works exhibited, as the five pieces (2003-2014) do not add much to the show’s stated endeavour to “explore the image at the moment of its fundamental reconfiguration”.

Mark Leckey, Inflatable Felix, 2014. Fabric model and fan. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin.

It is then for Sturtevant’s mantra of a tireless Labrador running from one end of the panorama projection to the other (Finite Infinite, 2010) to lead the show back to its purpose. While the piece may seem unimpressive at first, it develops compelling appeal in its endless loop and becomes the most significant when the perfect coordination of its four channel screens collapses for a split second, as the video ends then starts over again.

Sturtevant, Finite Infinite, 2010. HDCAM Metal Tape, four camera video installation 16/9, full wall projection, color, sound, infinite. Installation view Fridericianum. Photo Nicolas Wefers. Courtesy Estate Sturtevant, Paris; Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris/Salzburg.

This tiny imperfection, a necessary technical disturbance serves as an artefact within the artefact: just like the glitches and interruptions in the other works, it allows for a brief glimpse at the very core of the principles and conditions that tie these images together.

With: Cory Arcangel, Trisha Donnelly, Wade Guyton, Pierre Huyghe, Mark Leckey, Michel Majerus, Philippe Parreno, Seth Price, Sturtevant.

Related articles

Streaming from our eyes

by Gabriela Anco

Don’t Take It Too Seriously

by Patrice Joly

Déborah Bron & Camille Sevez

by Gabriela Anco