François Piron

In a globalized art world which you can dash round in 80 fairs, the biennale is now the exercise most favoured by curators, presenting as it does the great theoretical themes of the moment. Through its scope, but also because of its foothold in a presupposed territory, the biennale also traces the outlines of a specific work situation. For several weeks, the artistic diaspora ends up in one and the same space-time frame in order to install works, at the very least, if not produce them. Yet this state of affairs does not necessarily encompass the line of thinking about the material possibilities that are conditions of the biennale’s programme. To do this, the effect of the famous Zeitgeist must be added in, thus producing an alignment of the biennale planets, like the one we are witnessing at this very moment. To wit, an initial conjunction this summer of two of these events, each one broaching the theme of labour and economics: the 9th Berlin Biennale and the 11th Manifesta in Zurich. The first, in the hands of the New York collective DIS, brings together the heralds of the generation of artists who gathered together immediately after the stock market crash of 2008, those nomads of the digital age whose supremely polished, fluid and iridescent aesthetics flutter merrily in the arena of pack shots and stock photos. The second, more classical in style, and at times even anachronistic, curated by the German artist Christian Jankowski, rekindled the flame of the 1970s. The title, “What people do for money”, was deployed in a literal way, associating for the occasion different twosomes involving artists and local trades. A third event will be added to these two, come the autumn. In Rennes, François Piron has, for his part, chosen to take the theme of labour from the angle of the affects that it gives rise to within the context of a neo-liberal economy, whose wanderings and excesses are appearing to us more clearly than ever. An exhibition curator and art critic, and co-founder of the Castillo/Corrales project-space in Belleville, Paris, which closed its doors last December after eight years of activity, his project follows Zoë Gray’s “Playtime” inspired by games. Interview.

The affects created by the corporate world… such is the theme you’ve decided to develop for this fifth Rennes Biennale. What were the origins of that?

François Piron: A biennale is a context, within which the curator tries to include his own preoccupations. The Rennes Biennale immediately programmes the relations between the world of labour and the art milieu. For my part, this theme concerns me because I am persuaded that living and working conditions are of paramount importance in the way we can read a work of art, and also because they condition it. For this Biennale, I have merely started out from the world of work, or rather of business—the corporate world—, and focused more on the subsequent perceptible dimension: giving visibility, in a moment of crisis, to affects to do with tension, anxiety, and worry. This is the mood I’m in, and, more essentially, it’s a way of emphasizing the degree to which artists can be sensitive to their environment and to certain forms of topicality.

“Incorporated!” is its title, and it is definitely part of the economic semantic field but, for me, it is above all important to understand the idea of incorporation. Namely, how we are caught in systems from which we don’t necessarily know whether we can distance ourselves, or even escape—for me, the answer is no. It’s the symptoms of this incorporation, including in the purely physiological sense, that I wanted to highlight. It was also important for me not to start out from any theory about labour and work in particular, which would then be illustrated by the works. In so doing, I separate myself from the way a number of “theme biennales” proceed. I’ve chosen artists rather than works. These artists share in common the fact that they don’t base their work on a legitimization through the subject, or theme: they don’t have the position of interpreters, but makers of forms.

Luck of the timetable, mood of the times, or serendipity: just a few months apart, this biennale is the third one devoted to the condition of the neo-liberal world. It thus follows on from the 9th Berlin Biennale, which, under the aegis of the DIS collective, brought together the generation of artists which formed in the wake of the 2008 stock market crash, and from Manifesta 11 in Zurich, which, in a more classical perspective, got artists working with local trades. In your view, why is the biennale format capable of accommodating this type of reflection?

Probably more than any other format, the brief of the biennale is to react to the mood of the times. I think this is what DIS is trying to do, even if their viewpoint differs from mine. A biennale is a working situation with the artists involved, more so than in the case of an exhibition, which is often based above all on a selection of works chosen on the basis of precise criteria. The idea is not so much to define an object as to bring out a state of mind, which is done more by wagering on works. In Rennes, this is the case with two thirds of the works: so you don’t really know what it’s going to look like. It’s precisely this more intuitive aspect that interests me, whereas when I organize exhibitions, I focus more on the historical side and research.

For the artists who’ve produced works, what were the specifications?

I haven’t commissioned anything. The artists I’ve selected all, on the face of it, had good reasons to be there: I had no reason to make them veer away from their path. With some, the context made it possible to venture down new avenues. Camille Blatrix, for example, will be presenting for the first time a performance in the public place, put on by an actor. As a general rule, the dialogue I’ve had with the artists has focused on more abstract points, and on the slightly dark humour which sets the tone. I wanted tension. Some pieces keep the imprint of this. Ed Atkins will be showing his latest piece to date. It’s not a production, it’s already been presented, first of all at the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, this summer, then at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in Harlem, New York, which represents him. This video is more tense than usual and, to my eye, marks a turning point in his work. It’s less discursive: even if there’s still a pivotal character, he’s less talkative than usual and, above all, much more tragic and grotesque.

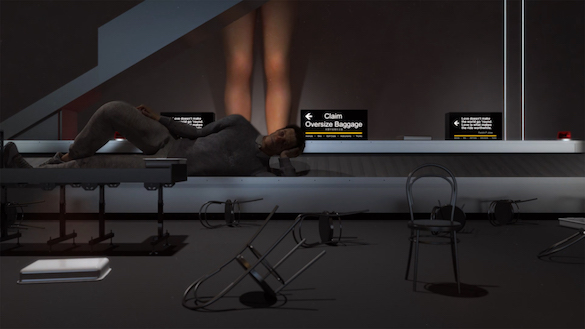

Melanie Gilligan, The Common Sense, 2014.

Film still. Courtesy Melanie Gilligan ; galerie Max Mayer, Düsseldorf.

In your previous curatorial proposals, there was already an interest in economics, labour, and the organizational systems of the art world. In 2007, alongside Thomas Boutoux and Nataša Petrešin, you embarked on a series of shows at Le Plateau in Paris. With “Société Anonyme”, what was involved was inviting different artists, collectives, and organizations to make their research process visible, making the preliminary stage of the show its actual subject. Ten years later, has your line of thinking evolved?

Hugely. In 2007, Paris really was in need of something else. The exhibition “Société Anonyme” was based on a period of isolationism in Parisian art circles. Above all, we wanted to import people who were no longer passing through Paris, and especially different work methods: collectives, and more process-based methods. In that same period, France was very object-based—it’s still the case, albeit to a lesser degree—and it seemed to us that it was crucial to get away from that. What’s more, it’s the exhibition which consolidated our own Castillo/Corrales collective and project-space, which we set up during the show. Today, these ideas are relatively integrated, and a certain number of institutions have been based on this loam, such as Bétonsalon and Khiasma, both coming from that generation.

In France, over the past ten years, we’ve witnessed the emergence of a generation focused around certain political subjects and stances, such as gender and post-colonial studies. Once again, I’ve had the feeling that I had to separate myself from all that: in order to take up an opposing position, I wanted to work with artists who are above all makers of things, who are engaged in a studio praxis, and have their own personal languages.

By emphasizing the emotions rooted in the body of the subject, you’re linking back up with a return to the individual and to the artist’s “ego” which has been taking shape for a few years now… For you, does the notion of “auto-fiction”, which is enjoying huge success in the field of literature, seem to have any equivalent in present-day artistic productions?

Even if there is, to be sure, this return to the subject, what interests me is not so much the re-emergence of an “ego” per se, but rather the fact of assuming that there may be a plural “ego” here, at times contradictory and caught in polarities. In the work of David Douard and Jean-Alain Corre, it is not so much principles of auto-fiction that are in question—even though it is perhaps possible to identify this logic to a certain extent in Jean-Alain Corre’s work—as this idea of being attuned to the world, in a relation that is at once desired and alienated.

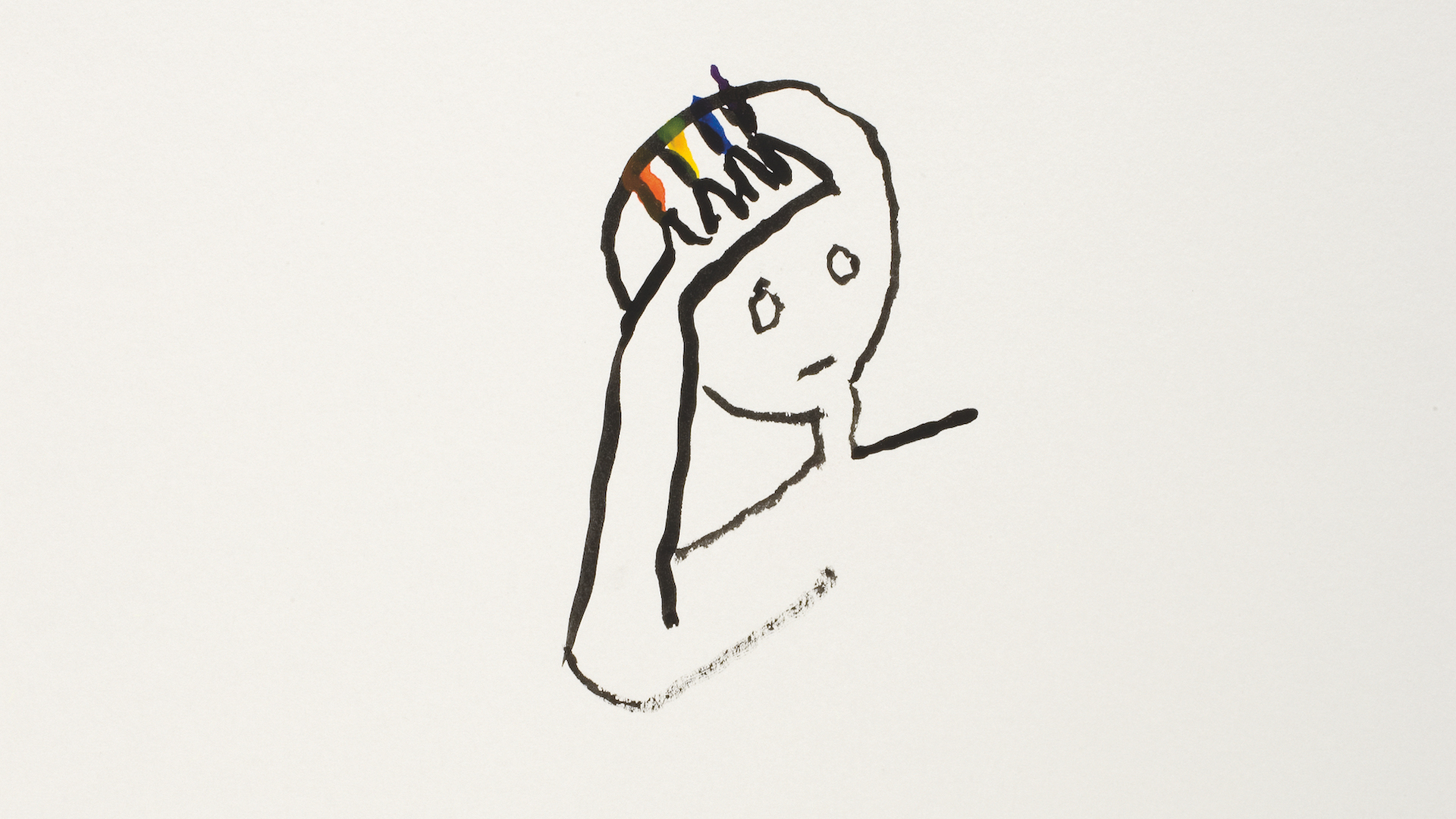

Jean-Alain Corre, & love. With Héloïse Bariol. « Double Je », Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2016.

Courtesy Jean-Alain Corre ; galerie Thomas Bernard – Cortex Athletico. Photo : Jean-Alain Corre.

Ismaïl Bahri, Revers, 2016. Film still. Courtesy Ismaïl Bahri. Produced by Les Ateliers de Rennes 2016 & La Criée centre d’art contemporain.

Let’s get back to the negative affects that you refer to. Here, you’re taking the exact opposite stance with regard to the DIS trend, and they, too, are working on the feelings created by the neo-liberal world, but showing its triumphant eros…

In a period of crisis, what was needed was a biennale of crisis. This type of event rarely has room for negativity. It just so happens that DIS lays claim to this non-criticism. In a way, Walter Benjamin adopted a similar position in the 1930s, when he declared that criticism was already dead, because the distance in relation to the object of criticism had become impossible. Essentially, it was already a matter of incorporation: as soon as you espouse a system, going back on it becomes extremely hard.

Even so, I personally don’t feel any great sense of well-being. I think that DIS generalizes the condition of a tiny category of people, consisting of the airport worker who is permanently connected. That isn’t my life, I think it’s the life of very few people and, in my view, the rest of the population undergoes more than it wants to. The most important and shareable concerns today have to do, in particular, with the creation of precariousness as much among people who are working as among those who aren’t working, people who are earning money, or earning very little, who are either in their own country, or outside it. Tristan Garcia has just written an essay about what he calls “intense life”, which seems to me to be an essential concept of the present paradigm. He demonstrates how this idea has been turned inside out, shifting from an avant-garde principle to an order to be always more.

It just so happens that I wanted to discuss that essay with you, but with regard to another aspect. At the end of the book, Tristan Garcia takes up a stance in favour of a right to complexity, referring to the way in which the deconstructive arguments of the 1980s ended up by producing the opposite effect, and, in their turn, becoming figures of authority. In your statement of intent, I get the impression that you agree with him on this point, when you talk about “emancipation in opacity”…

That’s quite right. I lay claim to the empirical and intuitive dimension; I arrange sensations on the basis of a hypothesis. Nowadays, I think it’s essential to think about the right to complexity, just as it is more important to lay claim to indecisiveness with regard to issues which are too complicated to be sorted out than to suggest directions and pinpoint enemies. Things that we’d thought were clear no longer are.

How can the exhibition draw attention to these ideas in ways that differ from those of a theoretical text?

In an exhibition, and even more so in a biennale, you show, you don’t demonstrate: it’s the arrangement of things between them that matters. To use DIS as a foil, they decide to bring similar people together. For me, the major task was to draw up a list of artists who don’t resemble one another, by balancing differing practices and trying to hold together positions that are as different as possible. For example, the relations between figuration and abstraction are very different, today, from what they were fifty years ago: you can depict abstractions and represent something abstract, which is what I wanted to convey by bringing in Jana Euler, who produces an extremely figurative form of painting, and Michaela Eichwald, because of her totally abstract contribution. This is the kind of dialectic that has been exercising me.

Michaela Eichwald, Der Möbelmarkt muss bleiben, 2016.

Courtesy Michaela Eichwald ; Silberkuppe, Berlin.

With the biennale, do you have the impression of making a critical gesture? Your formula of “emancipation in opacity” echoes the “mimetic excess” which Hal Foster talks about in his latest book, Bad New Days, which he identifies as the preferred, critical strategy of the last 25 years…

Yes, but not in the classical sense of institutional criticism or of a clearly expressed idea. But I do indeed produce the antithesis of something, namely, the celebratory practices of capital. I have very little belief in mimicry, and much more in the matter of individual language. Developing a language which you have to enter into, and which has to be deciphered in order to comprehend how it is organized seems much more substantial to me. This is what I’m talking about when I use words like “opacity” and “hermeticism”.

You talk about antithesis: so synthesis occurs in the onlooker’s mind, like a wager on his intelligence, without which the meaning could not emerge?

Absolutely. Trisha Donnelly’s works, for example, are like opaque and noiseless blocks, at once open and closed. She systematically refuses any discursive accompaniment for her installations, as well as any attempt to intellectualize them. The fact is that, for me, this type of form—irregular and personal, which everyone must let pass through them—is straightaway political.

- From the issue: 79

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion, Hoël Duret, CLEARING, Hanne Lippard, Nicolas Bourriaud,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton