Computer Grrrls

A conversation with Marie Lechner

March 1759: The Frenchwoman Nicole-Reine Lepaute assists the astronomer Jérôme Lalande and the mathematician Alexis Clairaut in their calculations to predict the return of Halley’s Comet but is “forgotten” in the book published by Clairaut the following year due to lover’s rivalry.

June 2018: Mattel launches the Robotics Engineer Barbie doll, and the journalistic review is without appeal: generally acclaimed by female editors, the doll designed in collaboration with a female MIT professor was greeted with unfailing condescension by male columnists.

In between: nearly two hundred and sixty years of more or less fruitful obliteration of women’s presence in science—it is incidentally quite tragic to see that the toy giant has waited so long to try to escape the sexist stereotype in which it had locked young girls for sixty years.

While the proportion of women working in new technologies has levelled off at between 24 and 30% in France and the United States, this has not always been the case. This would be tantamount to forgetting not only that the first program to be executed by a machine was created by Ada Lovelace (1842) and that the algorithm behind our present-day search engines is the work of Karen Spärck Jones (1972), but also that telephone operators and coders have long been predominantly… female.

This history, which has been long buried, is now emerging again in the writings of theorists and is increasingly apparent in the work of many artists, through the lens of an analysis of the contemporary situation: how many of our daily technological tools have been forged by men, knowing, as we do, that only 10% of Google’s researchers in artificial intelligence are female researchers?

From the fantasy of the mechanical maidservant (“Moll Handy”, 1740) to the exploitation of feminized chatbots (Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman, 2017), it is this history that curators Marie Lechner (La Gaîté Lyrique, Paris) and Inke Arns (HMKV, Dortmund) have taken a close look at to produce a manifesto exhibition: “Computer Grrrls”.

You have titled the first part of the exhibition “When Computers Wore Skirts”, to borrow the words of Katherine Johnson, a former NASA mathematician who calculated the trajectory of the spacecraft that propelled the first American into space, Alan Shepherd, in 1961, and who is one of the Hidden Figures highlighted in 2016 by the eponymous book and film that tell the story of those African-American women whose role in the American space conquest was crucial. However, the history that links women to information technology is much older, you have it starting in the eighteenth century… We didn’t wait until there were calculating machines to do complicated calculations, but before these machines, who did these calculations? When did we move from the “artisanal” calculation to the computating factory? For this exhibition, I was more specifically interested in those called “human computers”, those who did calculations by hand. The era of human computers began at the end of the 18th century and reached its peak during the Second World War before declining rapidly, and disappearing at the end of the 1960s. It was a fairly mixed profession at the outset, and was to become more female, particularly under the auspices of Edward Charles Pickering. Appointed director of the Harvard University Observatory in 1877, he systematically recruited women to process astronomical data and classify stars.

As Claire Evans reminded us during the talk she gave at the opening of the exhibition: “Harvard’s women computers designed the sky chart for a minimum wage”.

Indeed, it was not that Pickering was particularly progressive, but rather that economic interest was the main reason for his choice. Women had the advantage of working for half the salary of men, which made it possible to double the computing power of the observatory for the same price. Several of those computers became famous astronomers in their time, including Williamina Fleming, Annie Jump Cannon, Henrietta Swan Leavitt… With the Second World War, the demand for computing exploded for ballistic trajectories, shock wave propagation, navigation tables, decoding. The labour shortage stepped up the arrival of women in these computing occupations to the point where, as David Grier1 writes, “sometime in 1944, computers became girls”. There was even an ephemeral “kilogirl” unit that probably refers to a thousand hours of calculation done by a woman.

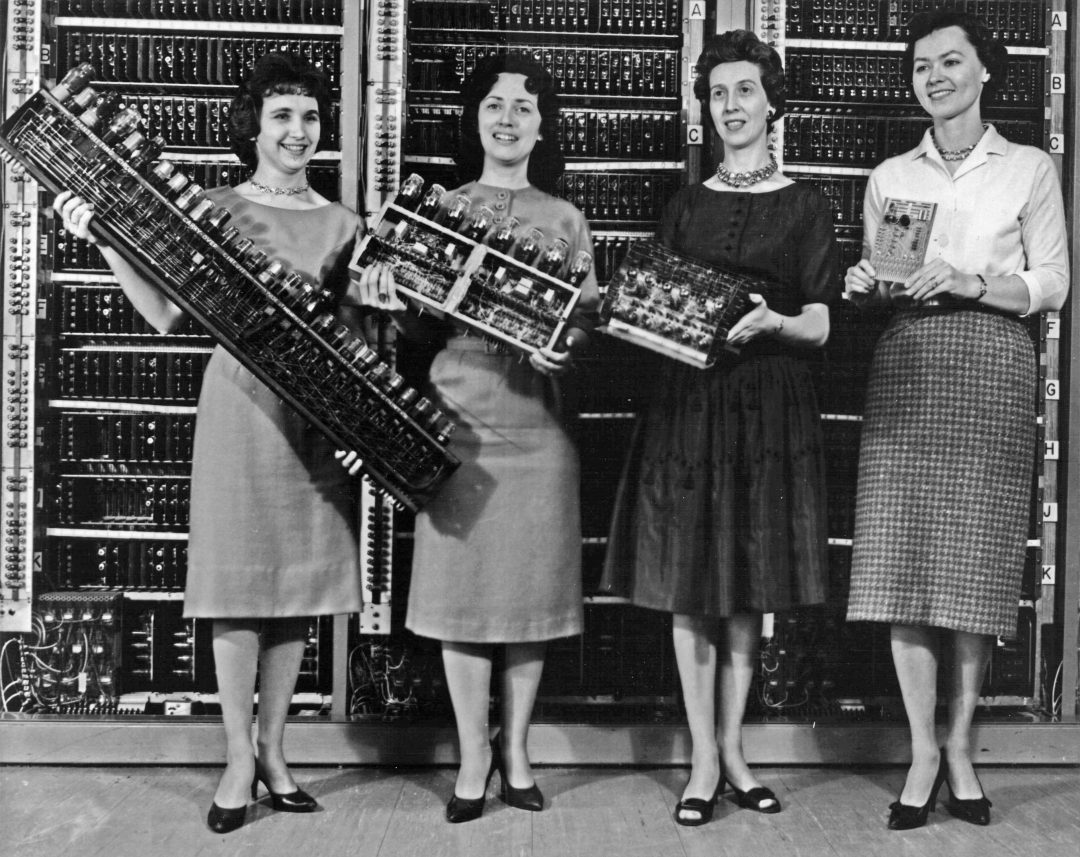

The six women who, in 1945, programmed ENIAC—the first fully electronic computer—were also recruited from among the best human computers responsible for calculating firing trajectories during the war. Ballistics is mainly what ENIAC was designed for, unlike the Colossus (British) which was designed for cryptoanalysis. But in both cases, it was women who programmed these machines. It is important to point this out because, for a long time, these women have been erased from the images; putting them back in the spotlight is a recent phenomenon, particularly following Kathy Kleiman’s documentary, The Computers, released in 2014, and Hidden Figures released two years later. David Alan Grier’s When Computers Were Humans (2005) traces the evolution of computation, the transition from cottage industry to De Prony computation, through mathematical tables based on Adam Smith’s division of labour model. The calculation was thus segmented and organized like factory work. Today, many researchers and artists are revisiting this history, echoing the cottage industry that digital labour represents today, the neo-parcellisation of work on micro-task platforms. When I think about that, it is the same images that come to my mind.

It is quite incredible to think that at the beginning, IT was a very female field, given the image of it that is mainly conveyed today…

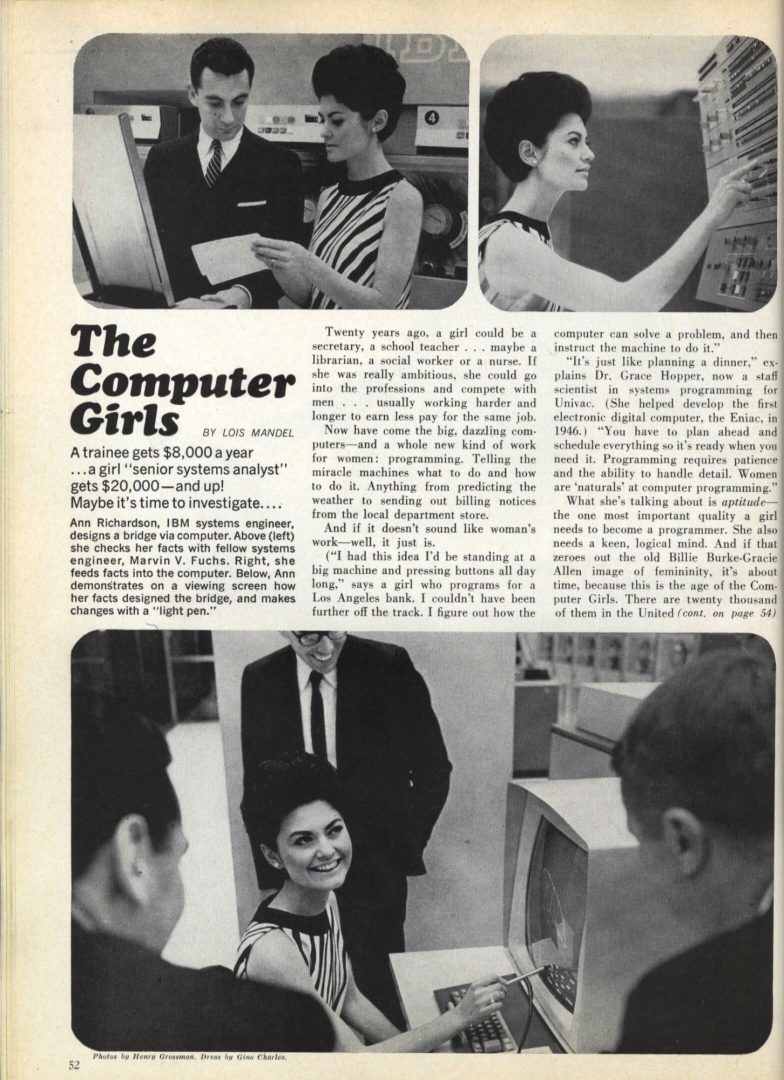

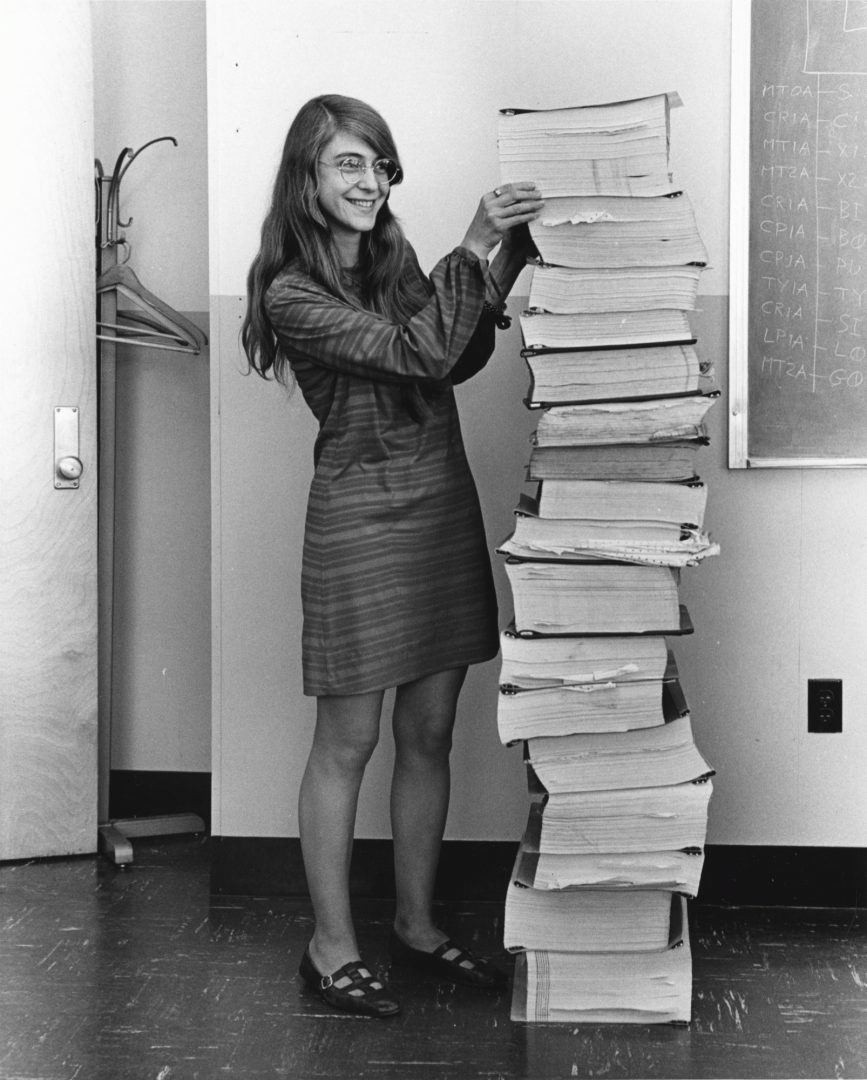

In 1967, Cosmopolitan magazine published an article titled “The Computer Girls” that praised career opportunities for women in IT. Paradoxically, however, it is at this point that we observe the beginnings of a masculinization of the profession. This article is quoted by Nathan Ensmenger in his book The Computer Boys Take Over (2010), which is the counterpart of our history and tells of the arrival of men in a very feminized profession: there were women at all levels, both in computer science laboratories and in data entry. Throughout the 1960s, the evolution of computer professions put the brakes on women’s participation. As a low-level, administrative and mostly female activity, computer programming was gradually and deliberately being transformed into a high-level scientific and male discipline. To attract men to this feminized profession, it was necessary to reshape the image of programming, to make it an intellectual and logical art, accomplished by do-it-yourself and anti-social geniuses. It was at this point that the vocabulary evolved: “coders” became “software engineers”. It was a whole construction of the imagery of the profession that was being set up, further expanded with the arrival of personal computers whose marketing, aimed at men and their sons, participated in the creation of a very masculine computer culture that spanned several decades, with the emergence of the nerd character in the eighties, underwritten by cinema in films like Revenge of the Nerds. And the illustrations associated with Cosmopolitan’s article did nothing to help because the woman in them is quite decorative, it is no longer the same type of photo as the famous portrait of Margaret Hamilton—the engineer standing next to a pile of paper as high as herself, covered with the code she wrote for the Apollo landing module, for example, or the images of ENIAC girls in the process of wiring.

Margaret Hamilton, lead software engineer of the Apollo Project, stands next to the code she wrote by hand that was used to take humanity to the moon. Public Domain.

Throughout this history, we are guided by a gender logic as binary as code, if I may say so, which reflects a parallel historical actuality: according to a number of anthropologists, sexual identification in a strict binary mode would go back to the early days of the nineteenth century with the advent of modern biology and medicine…

In the nineties, the Internet exploded with its share of fantasies and hopes. Cyberfeminists were calling both for involvementin the emerging web, again mainly staffed by men, and for appropriation of these new information technologies to make them a tool for emancipation, a tool for self-reinvention in cyberspace… In 1991, the Australian women of VNS Matrix published their Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, which is a tribute to Donna Haraway’s cyborg, a figure at once mythical and real that helps us rethink our bodies in relation to technology and rethink paradigms that, until then, were based on binary oppositions (body/machine, man/woman, culture/nature, etc.). Her cyborg, a symbol of a post-gender future, is often considered as the starting point of cyberfeminist thinking even though she herself has never used this term. VNS Matrix infiltrate communication networks by appropriating often misogynistic imagery, images from cyberpunk literature where women are represented as passive objects of male desire (cyberbimbo) or as a metaphor for a threatening and uncontrolled technology (the fembot/vamp). The first game produced by VNS Matrix was an arcade game. When users logged in, they were offered three options: male, female or neither, and they had to select “neither” to be able to access the game; the idea of gender fluidity was already present in cyberspace. That said, we did not want to produce a historical exhibition. The context is set by the large historical frieze that opens the exhibition but we wanted to focus on works produced today. And even when the works deal with historical technologies, it was important that the point of view relating to them be contemporary. For example, Jenny Odell works a lot with archives but she looks at them from her situation as a digital native. I am more interested in what women have to say about technology today than in a story from the past.

While in residence at the Internet Archive, Jenny Odell discovered the 1988 computer animation, Polly Gone, directed by Shelley Lake, a surrealist dystopia inspired by Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet featuring a household robot in a futuristic domestic universe with a score inspired by the first “great” American science fiction film, The Day the Earth Stopped (1951); she revisits it in the anxiety-provoking Polly Returns which she made in 2017, where the robot is bombarded with titles of contemporary listicles—those clickbait articles that are more lists than real articles—, which give her in particular “fifteen ways to make chocolate chip cookies”, “two ways to think about nothing”, “five ways to increase [her] productivity” and “six ways to have radically intimate sex”. Jenny Odell is also presenting Neo-Surreal (2017), a series of advertisements taken from the computer magazine BYTE with which, by a simple gesture of erasing the texts, she highlights the very strong imaginations linked to digital technologies since the 1980s: disappearance of women, militarization, masculinization, via elements such as whips, weapons and biometrics, in a work that she claims to be the counterpart of Richard Prince’s Cowboys. Lauren Moffatt works with old technologies to produce 3D images. In The Unbiding (2014), a kind of time machine, she reinvents an old 1830s medium, stereoscopy, with which she makes black and white video collages. She thus produces a moving female figure composed of fragments of pioneers of the history that interests us here, such as Ada Lovelace and Mary Shelley. This figure in constant recomposition is inspired by the scramble suit devised by K. Dick, that costume which is constantly changing to escape optical recognition machines. And in her Robotron web series, Nadja Buttendorf shows the lives of the employees of a factory in the Robotron combine, specialized in computer manufacturing, in the former GDR. The artist plays all the roles in this relational drama inspired by the story of her parents, both of whom worked at Robotron.

The analogy between the Luddites and Kim Kardashian2 created by Lauren Huret in her video Breaking the Internet is quite impressive. Reminding us that one had to be single and virgin to be a “hello girl”—those “Vigilant Virgins to whose voices we listen every day without ever coming to know their faces” as Proust described them—, to be a “Voice with a Smile ”, a voice without a body, “to relay the chatter of women and the orders of men” but, above all, she spins the metaphor of the loom to the limit, from Jacquard’s invention—to put an end to child labour—to the “voiceless and fabricless body” of the starlet which “causes a cut in the network, a tear in the web”.

Or how to move from machine breakers to an attempt to destroy “the” machine. “The voice with a Smile” is a glamorous metonym for describing the hard work of women telephone operators who, in the last century, played a central role in the development of global communications. They are the forgotten heroines of Caroline Martel’s film The Phantom of the Operator, a dreamlike collage of some 125 clips from promotional and industrial films produced between 1903 and 1989 that revisits this little-known episode of the female workforce, this army of shadows made superfluous by the automation of telephone switchboards.

It seems that humans have never had an easy relationship with technology, that they have oscillated from the beginning between anxiety and fascination for their own productions…

That’s true enough. And it is not Aleksandra Domanović’s Vukosava that will contradict this idea: it is the 3D printing reproduction of the Belgrade Hand, the first prehensile artificial hand (invented in 1963) that finds itself rather incongruously the protagonist of the first domotic horror film, Demon Seed (1977), which pushes anxiety and fascination with robotics to its paroxysm. It is the story of an artificial intelligence that invades the home automation system of its inventor, holds his wife prisoner and then sexually assaults her until impregnation with the robotic arm that serves as its prosthesis. And thirty years later, last summer to be precise, The New York Times3 published an article warning of new forms of domestic violence related to smart homes, including smart locks and thermostats used by men to monitor, harass or abuse their partners by overheating or , in an impromptu way, cooling the house, changing lock codes without warning…

This leads us to the question of resistance tactics…

Yes, many and above all very varied tactics. While the 1990s saw the birth of the first cyberfeminist movements calling on women to reclaim new technologies and get involved in the emerging Internet, this wave of thought, criticism and art galvanized a whole generation of women theorists, artists and activists who developed new ways of thinking and acting in the age of networks. This includes opposing programmed obsolescence and innovation propaganda. Darsha Hewitt, for example, makes a feminist critique of technology by focusing on demystifying the systems of power and control embedded in the products of capitalist culture. For A Side Man 5000 Adventure (2015), she deconstructed, in a series of ten videos, the first drum machine marketed in 1959—a device designed to be repaired—and demonstrated that it can still be repaired today! She is currently working on the Soviet lawnmower, which was also particularly easy to repair, and is one of those iconic objects from East Germany. As far as millennials are concerned, the DIY factor is also present, as in Dasha Ilina’s Center for Technological Pain (2018), a parody of a start-up that offers solutions to health problems related to technological objects such as illustrated guides with Ikeaesque designs to improve the posture of smartphone users or self-defence techniques explained in absurd tutorials to address their anti-social behaviour when they walk around the city without looking around them.

Most of the “resistance” works on view in the exhibition approach the subject with humour, the climax being, for me, Mary Maggic’s Housewives Making Drugs (2017) with their recipe for an œstro-gin cocktail presented in the form of a culinary show campaigning for the therapeutic independence of transgender people through a hormonal therapy that could not be more DIY. We have here a hilarious film that tackles an obviously prickly question, that of access to health care, through a short history of biohacking…

Tabita Rezaire, on the other hand, proposes a more ambivalent form, humorous but against a backdrop of colonialism’s tragedy, which attempts to break the unilateral Western narrative on technology. In Premium Connect (2017), she describes the Internet as a tool of American imperialism, aimed at the spread of northern culture and at the crushing of indigenous cultures. It is a film that puts the case for other forms of connection— connections with ancestors, connections with plants, other methods than those involving our electronic tools—and that calls for a rethinking of Africa’s heritage in the history of technology. Her video echoes the research of ethno-mathematician Ron Eglash on fractals that can be found in the way hair is braided and also in the vernacular architecture of African villages. She also refers to the work of the Nigerian philosopher Sophie Oluwole, which shows that the binary code could have its source in the divination system of the Yoruba, a Nigerian people. Sophie Oluwole, the first woman to hold a doctorate in philosophy in Nigeria, was very focused on the issues of women’s representation and, more generally, on African thinkers in the field of philosophy.

Speaking of representation, the question of the body seems to me to run through the whole exhibition, in particular through the staging of very incarnated points of view: we really do see a lot of women in all these works!

Yes, and even when we gradually slide towards the idea of disembodiment in the exhibition. Technologies of Care (2016) by Elisa Giardina Papa approaches digital work—therefore remote, therefore disembodied…—from the point of view of what comes under ‘care’, i.e. what modifies the emotions of the people who receive it: this may of course mean services with a sexual connotation such as the creation of fetishist videos, the optimization of your Tinder profile, or simply comments and likes about your posts on Instagram…

What interests me most is this notion of virtual immigrants that she puts to the fore when she talks about this series of videos, because these workers all operate via microwork platforms usually from their home country—countries in the Global South such as Brazil, Greece, the Philippines, Venezuela—but are paid in dollars as most of the people or companies that hire them are located in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom…

The fluidity of the body is also strongly reflected in Lu Yang’s video, Delusional Mandala (2015) in which we follow a post-sexual, gender-neutral avatar from its creation until its death. As for Simone C. Niquille, she looks into the anthropometric standards encoded in 3D modeling software and the way people represent themselves online. In the video she presents here, The Fragility of Life (2017-18), she focuses on the moment when we lose touch with representation. In the video we follow a famous Hillary Clinton look-alike, Teresa Barnwell, who recounts, as an organic double, the difficulty of accommodating someone else’s personality in her body. Speaking of cross-border body fluidity, she was even sent to the Ecuadorian Embassy in London to take a picture with Julian Assange… The other protagonist of the film is an avatar nicknamed Kritios, made with the 3D character creation software Fuse, which the artist pushes to its limits. Who sets the parameters in modelling software and decides what is human and what is not? To explore these questions, Simone Niquille sent the same drawing of Kritios to two factories that produce inflatable objects, one in the Netherlands and one in China, and it is clear that from the same specifications, the products are very different, based on the cultural contexts of production. What fascinated me, when I delved into the website of the Chinese company, was to discover that, in addition to bouncy castles and other festive structures, it also and even mainly produces decoys for the Chinese army: tanks, missiles, all kinds of inflatable weapons. 3D scanning technologies came into being in the entertainment world, were co-opted by the military and then returned to the entertainment field.

That is to say the reverse path of a certain number of technologies, including computers and the Internet, financed by the military for military purposes, which became accessible to the general public and then fell back into the hands of state surveillance agencies via social networks and data extraction in particular…

Inke Arns and I chose to commission a technofeminist search engine from the graphic designer Manetta Berends, to help us explore a corpus of technofeminist manifestos that we had gathered. Cyber/technofeminist cross-readings (2019) is based on the TD-IDF algorithm, which is one of the algorithms used by Google to weight searches: it inventories the number of times a term is mentioned in a document in relation to the length of the document and thus infers its importance, while the other algorithm analyses the importance of a word within a document in relation to a body of text. For example, if we look at the Cyborg Manifesto, the more a word appears in it, the greater its TD-IDF value: it allows us to read a text through the prism of a reading algorithm, to see the value it gives to words. And the cross-reading function allows you to search for the word “cyborg” in all the selected manifestos, for example, and then classify them according to the logic of TD-IDF, i.e. in their order of importance with regard to this term. TD-IDF is a historically crucial algorithm developed by British computer scientist Karen Spärck Jones, a pioneer in automatic natural language processing, who laid the foundations, in 1972, for search engines as we now know them, by combining statistics with linguistics. The researcher also campaigned strongly for the place of women in data-processing and computer science, repeating in particular that computing is too important to be left to men.4

1 David Alan Grier, When Computers Were Humans, 2005, Princeton University Press.

2 David Hershkovits, “How Kim Kardashian broke the internet with her butt”, The Guardian, 17 Dec. 2014

3 Nellie Bowles, “Thermostats, Locks and Lights: Digital Tools of Domestic Abuse”, The New York Times, 23 June 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/23/technology/smart-home-devices-domestic-abuse.html

4 Nellie Bowles, “Overlooked No More: Karen Sparck Jones, Who Established the Basis for Search Engines”, The New York Times, 2 January 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/02/obituaries/karen-sparck-jones-overlooked.html

Image on top: Nadja Buttendorf, Robotron – a tech opera, 2018-19. Web series. Courtesy Nadja Buttendorf.

Computer Grrrls

Mu, Eindhoven

08/09.2019

La Gaîté Lyrique, Paris

14.03—14.07.2019

HMKV, Dortmund

26.10—24.02.2019

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Paolo Cirio, Sylvain Darrifourcq, Franz Wanner, Jonas Lund, Heather Dewey-Hagborg,

Related articles

La Contemporaine at Nîmes, Anna Labouze & Keimis Henni

by Elora Weil-Engerer

Anna Longo

by Clémence Agnez

Anne-Claire Duprat

by Vanessa Morisset