Jonas Lund

Jonas Lund applies the methods of quantification and data analysis that now prevail in many areas of contemporary society to a well-defined field: art. In 2013, he wrote an algorithm that analyzed a significant number of works by some of the most recognized artists on the international scene in order to produce instructions for making “successful” works, it was The Fear Of Missing Out. That same year, he produced Gallery Analytics, a software program that recorded and analyzed the movements of visitors in an exhibition to study the, once again, most successful pieces. The following year, he transformed one of his online exhibitions into an advertising space whose price was indexed to a rate close to the average annual return on investment in contemporary art. In 2015, it was through a series of paintings (Strings Attached) that he explored the bubble of the contemporary art market, each of those carrying a statement compelling its sale or resale. If measuring the value of art still seems meaningless even though this value is precisely the foundation of the art world and its market, then perhaps one of its keys lies, as Duchamp claimed, on the onlooker’s side? When we conceived Critical Mass together last year, we sought to base our exhibition on the feelings of its visitors, via a feedback loop, so that the exhibition in turn would react to the reactions it provoked. Jonas Lund has now opened his artistic capital to new shareholders in his practice by creating his own cryptocurrency exploring the tensions between economic incentives and qualitative choices in a relationship that seems by necessity win-win. At the same time, he uses tools accessible to everyone—individuals, companies or even data brokers like Cambridge Analytica—wishing to make themselves known or propagate information: Facebook, Instagram and others, in order to reveal some of the workings of these opinion makers. Through the micro-targeting of its own audience, Hi Munich! can also be seen as ironically reflecting on the narrowness of the art world in general, on the very limited reception that most artworks meet as, when we think of art, today, we think of a rather small bubble, of objects that are barely shown a few times in galleries and fairs that mainly professionals attend and that, if they are sold, in most cases end up ‘hidden’ in some private collection or storage, when it’s not in crates in some free port.

My interpretation of Hi Munich! might not be that close to what you had in mind when you conceived this new project of yours… The heart of that project is a mix of engineering consent and computational politics. More precisely, it’s an ongoing performative piece taking place on Facebook: on each day of its duration, a new ad campaign will target a specific subset of people living in Munich. Munich, as it is part of Public Art Munich, which second edition claims to “present art in the public sphere, not just in public space”… Public Art Munich (PAM) is indeed this time a performance project, curated by Joanna Warsza (five years ago, it was a sculpture project curated by Elmgreen & Dragset). So your project spreads on the web, and more specifically on Facebook and Instagram: is that to say that, although privately owned, you may be inclined to describe those platforms as public sphere? The public sphere, in the classical, albeit contested, sense of the word, is a space where rational conversations and arguments concerning the public, with a focus on governance and the civics, can occur. In actuality, today, most of these conversations and arguments are taking place online. That said, describing Facebook as the current representation of a town square would be erroneous based on a couple of fundamental differences. First, Facebook is a corporation with complete control over the protocol in which the conversations can occur, thus not an open and public forum, rather a closed and private forum owned by a massively profitable company based in California. Secondly, Facebook and other online platforms have given rise to the ability to observe, surveil and collect everything you do, and I mean everything you do, every click, every scroll, every comment, every beginning of a sentence in a comment box that you deleted and never sent, every gesture is recorded and used to create a profile of your behaviour. The profile of you is then used for a plethora of different things, but in the case of Facebook, it’s the basis of their business model, to use your profile to sell your attention to the highest bidder, the advertiser. Then you place yourself in the position of an advertiser, feeding their system the better to expose it… With Hi Munich!, I’m using Facebook’s advertising platform to create daily unique ad campaigns that function as portraits of groups of people based on their interests. I’m instrumentalizing the platform that Facebook is offering to anyone who’s willing to pay. On the website hi-munich.club, you can find detailed statistics of all the ads that have been run so far, you can see the actual ads, how many clicks they generate, how many impressions. The website is there to make the whole mechanism visible. There is also a Facebook pixel on this website, which will then create a new target group of everybody who visited it, so then I can target these people again. In the advertising world, it’s called retargeting, you know, when you browse some product online and then for weeks after you see ads that feature that product… The online shop knows that you were searching for it by loading the Facebook pixel and can thus target you again. The website is also showing all the advertisement that PAM as an institution does as well, as they also use Facebook to promote their events and boost their posts—boosting meaning that they pay to get more visibility—, so the statistics also incorporate the normal advertisement that PAM does. All the institutions embrace it while, at the same time, they are critical of it, but can you be critical of a tool if you also rely on it for your promotion?

Let’s get into details, what are these ads like? They are fairly descriptive. The granularity in how you can target people on Facebook its truly astonishing: in Munich, 7 200 people between the age of 26 and 38 like to travel and are in a long distance relationship—that one makes sense, long distance relationship equals lots of travel; 4 000 people between the age of 22 and 40 are newly engaged (1 year), have an upcoming birthday and are “away from family”; 18 000 people are interested in contemporary art, curation and have a monthly income about 5 000 €. There’s currently around 300 000 different interest categories that are available to you when you chose your target group, and that’s just interests. All personal details are available as well, such as language, location, relationship status, education, income, work, employers, what kind of house you live in, ethnicity, important life events, and for the US population only: political affiliation. You are part of many communities without even noticing it: Facebook assigns them to you. And visually speaking? Facebook has text detection tools, so if you put text in your ad, it will not be displayed, that’s why all the ads are handwritten drawings by me. Because their software doesn’t recognise (yet) handwritten text as text? Exactly. And so only Munich inhabitants can see these ads? I mean, on their feeds… Yes, due to the targeting nature of the piece, it’s directly addressing the population of Munich. There are two exceptions, the website visitor custom audience based on the Facebook pixel, and the custom PAM audience that targets everyone who has interacted with the PAM Facebook page.

They’re like a test group, in a way. They are a test group for your art, but they also mirror the ones established by Facebook for its own testing, such as the famous 2012 massive experiment about emotional contagion for which the feeds of over 700 000 users had been manipulated. The example of Facebook manipulating their news feed ranking algorithm to create specific emotional responses is just a further example of how Facebook is not a traditional public space, as the protocol is opaque and the control is completely in their hands. Imagine the amount of power you have when you can manipulate people’s responses like that, and we are in a position where we just have to take Facebook’s word for it that they won’t use their platform to, for example, manipulate elections. So you’re only using existing categories in Facebook’s target groups and combining them, like every advertiser? Yes. Sometimes I even use the same groups that Public Art Munich uses to promote their event (Modern art, Theatre, Visual arts, Contemporary art, Arts and music, Museum, Performing arts, Culture, Sports, Public art, Nature or Sports and outdoors and Field of study: Contemporary art). We’ll see how it plays out, with its performative aspect, it will of course change, as with every ad campaign that is enabled by Facebook, you get statistics and analytics, which inform your next decision and how you should shape your campaign in order to be more successful. That’s where the click-through rate comes in, which is a measurement that determines how many clicks per thousand impressions you get, so if a hundred people, out of a thousand who see it, click on the ad, you get a 10% click-through rate, which is extremely high—most of the time this rate is below 1%. From there, you can try to optimise your campaign to increase this rate. So far, the most successful ad in the project has been the “free beer” ad, running on this Simpsons’ inspired joke: “Free beer, now that I have your attention…” to promote my talk during PAM’s opening, which means that “free beer” is the text that made the most people click in a target group of people between 20 and 30 years old who like beer and contemporary art. It’s interesting to think about what computational politics mean, about how you engineer consent. Computational politics in this case refers to politics that are informed by big data, algorithms and modeling, and we’re just beginning to see the effects of these systems on the political discourse and elections, to see how micro-targeting and modeling enable highly precise targeted messages to influence voters and engineer consent. And also on a purely artistic level! With this piece and its level of analytics, I can exactly say: this artwork touched that many people because, in order to click on an ad, you have to be in a way moved by it, you don’t click on it if you’re not curious about it. Most artworks that are produced don’t have this level of analytics attached to them, you can’t have that with a sculpture or a performance, you don’t have surveys that ask you if you are satisfied with the experience of the work. It’s not how you evaluate art.

Jonas Lund, Critical Mass (We Show You What You Want To See), 2017. Digital painting on canvas, 100 x 190 x 4 cm.

Produced by Galerie Édouard-Manet, Gennevilliers.

This question of the evaluation of the artwork is a recurrent one in your work, could that mean that you are, personally, disappointed just like me by the pragmatist answer stating that is an artwork what is recognised as such by the art world? The institutional theory of art by George Dickie is still to me the de facto standard for determining what is art, but this theory is critiqued for its circular nature, in the sense that it doesn’t actually contribute much meaning to the understanding of art, and it’s also missing the point, the question is not wether something is art or not, but rather if it has an effect or any consequences. Alas, the theory still holds, and it’s an interesting way of observing how value is created and how works are evaluated in the contemporary art world.

From Studio Practice in which you were delegating a part of your judgment to a committee composed of other artists, art advisors, gallerists and collectors to decide if the works produced by your assistants were good enough for you to sign them, to Critical Mass in which we were crowdsourcing the curatorial decisions to the visitors through a website designed as a video game-like voting platform, you’ve been exploring this idea that, actually, it’s mainly the others who decide, in a satirical way of restating the duchampian “it’s the onlooker who makes the work”… The nature of these works is slightly different, but they share the same systematic approach to distributing agency, influence and power or certain decisions, or at least seemingly do so. In the case of Studio Practice, I had the final say for all the decisions, so it’s more about making visible a certain evaluation strategy, creating a whole system and infrastructure for the production, evaluation, consensus building and mediation of works of art. In the case of Critical Mass, the influence is evenly distributed among the online audience, to which I give up more of the control over the final outcome, as a speculative approach to value creation and meaning building.

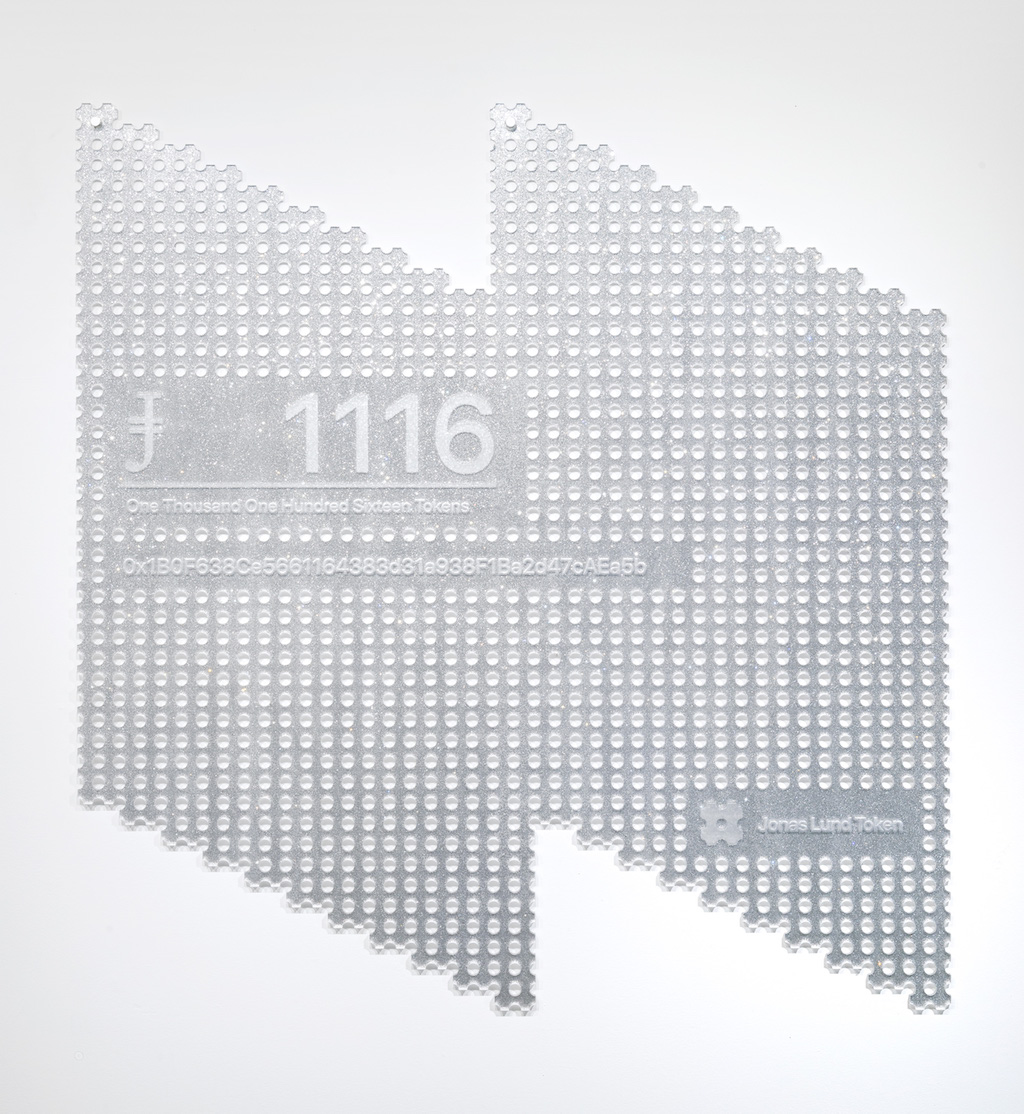

Jonas Lund, JLT 1116, 2018. CNC and engraved acrylic, 161,3 × 161,3 × 1.3 cm. Installation view, Castor Gallery, New York.

Now you’re pushing this logic one step further with the Jonas Lund Token with which you’re becoming a sort of brand, as you’re opening your artistic practice to shareholders if I can put it this way… Yes, so the Jonas Lund Token (JLT) is a cryptocurrency built on top of Ethereum, that gives its owners voting rights over all future decisions concerning my artistic practice and the token itself. There’s a 100,000 total tokens that will be distributed in different phases, the first being me giving away around 10,000 of them to form the initial advisory board, and each token gives you one vote. The Jonas Lund Tokens create a system in which the people who I distribute agency to, the token holders, have a financial incentive to reach a consensus for what’s the best strategic decision. The logic being that the better my career is doing, the more valuable the token becomes and the more value the token holders receive. It’s a way to explore new methods of governance, of distributed decisions models and giving away parts of my agency.

Some tokens are also for sale in the form of artworks, if I got it right, meaning you allow people to buy some power over you? Yes, the second phase of the distribution process is through sales of Jonas Lund Token artworks. Each artwork comes with x amount of tokens attached to it, and the owner gets access to these ones upon a successful purchase. In essence you can buy voting power, yes. The third phase of the distribution process happens through what’s called an ICO, which stands for initial coin offering, which,a in a nutshell, functions as a sort of crowdsales, and then the tokens are available for purchase by anyone. So yes, those three projects relate to each other in different ways of looking into different types of consensus, of engineering consent, of reaching consensus in terms of distributed influence, from Studio Practice (who gets to determine what’s quality and what’s not quality?) to an online anonymous crowd in Critical Mass who had influence over what happened in the exhibition and who could increase their influence and then, with the JLT, it’s an instrumentalized version of power distribution: who gets to determine what? And, in parallel to this, Hi Munich! looks into different tools you can use to sway, to engineer shifts…

Public Art Munich 2018: “Game Changers”, 30.04—27.07.2018, hi-munich.club

“Pizza is God” NRW-Forum, Dusseldorf, 16.2.-20.5.2018

The Jonas Lund Token, https://jlt.ltd/

“Proof of Work”, Schinkel Pavilion, Berlin, 7.09-28.10.2018

(Image on top: Jonas Lund, Hi Munich!, 2018. Ad.)

- From the issue: 86

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Paolo Cirio, Sylvain Darrifourcq, Computer Grrrls, Franz Wanner, Heather Dewey-Hagborg,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton