Florence Jung

« D’autres déroulements auraient pu se produire, d’autres révolutions, entre d’autres gens à notre place, avec d’autres noms, des autres durées auraient pu avoir lieu, plus longues ou plus courtes, d’autres histoires d’oublis, de chute verticale dans l’oubli, d’accès foudroyants à d’autres mémoires, d’autres nuits longues, d’amour sans fin, que sais-je ? »1 Marguerite Duras’ words could well apply to Florence Jung’s artistic practice. The artist’s immaterial scenarios creep between the lines without the knowledge of those who become the protagonists. Although often invisible, her scripted work is still quite tangible: evident and astutely discreet, it envelops us even before we seize it. Jung’s work is rarely materialized by objects and the artist does not produce any images. Exhibition view has no place to archive and transmit aesthetics that develop through direct experience, rumors, and their echoes on social media as its only medium of dissemination. From the simplicity of a situation unfolding before our eyes, a form of strangeness is born that nurtures the fictional potential contained by reality.

Whether one gleans the amateur images of her work or reads the ninety-page file of texts on her practice, something evasive emerges from the whole. These fragments answer each other in a cacophony resembling the hubbub of a station hall, full of mysteries and contradictions. Florence Jung displays a radical posture going against the flow of image control and the notion of authorship. While waiting to encounter with her work amidst the perceived emptiness of her exhibition, one is seized with a certain apprehension. When does participation begin? How far can one venture to see and understand? Should one resist the desire for challenge, and at what cost? Staging starts as soon as the idea of a narrative takes shape. The apparent opacity of her methods positions us in a grey zone between action and reflection, playing with the ambiguity of this boundary. Whether we decide to act or not, we are already under tension. And is it not there, in this interstice, that emancipation, as Jacques Rancière2 defines it, occurs?

Since 2012, Florence Jung has been developing a practice that lies between art, performance and text. For her first exhibition, she initiated her practice by inviting four people wearing perfume to infiltrate the opening of an exhibition preview. Although not explicitly required, the spectator’s participation in Jung’s work was effectively operated by the suggestion of this disruptive element, announced orally but not directly detectable. Thanks to the element of social distinction that perfume represents, Jung also questioned the systems of art and society, both of them molded in rituals and spectacle. From this date on, her rejection of an objectifying title led her to set up a system of archival numbering of her pieces, made up of her surname and a number (Jung10, Jung11, Jung12…) Florence Jung’s scenarios feed on the unforeseen of a subjective reality where everyone takes part in the realization of the initial script. Their written formulation is a short description. Simple, factual and distanced, it does not indicate any direct intention. Besides deconstructing some codes of contemporary art and questioning the materiality and irrefutability of artworks, the only thing that the scripts have in common is that they have all entered into reality.

Even more than the protocol structure, then, it is the infiltration of fiction and doubt that constitutes the real inner workings of her devices. The writing of the scenarios proposes an architecture in which everyone can choose whether to venture or not, and which unfolds over time – often, even, beyond the temporality during which takes place. Reality and what it contains of a priori insignificant nurture the work, which transforms itself as one experiences it. The object develops, hybridizes itself in one’s memories, and is shaped by its reappearances and marks. In the empty spaces of the museum or in the contexts she uses as her sets, Florence Jung scatters the clues of a movie in the making as the many possible paths for the writing of the next story, the one experienced by the visitor.

The way she constructs her situations invites one to scrutinize social practices and contemporary alienations. Each site is the source of a context and an ecosystem from which the artist draws inspiration to elaborate and activate her scenarios. After her stay at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam and as a reaction to the voyeuristic nature of the conventional openings of artists’ studios, she proposed to explore an inhabited apartment, as if suddenly left after breakfast. In the vain search for traces and identifiable plastic forms, the visitor was confronted with his or her own capacity for transgression in a private place where he or she was not quite invited. At the same time, hidden from view, a packet of matches marked with the name of a bar located equidistant between the Rijskakademie and the apartment where the scenario was taking place was slipped into the pocket of the coat or bag that the spectators had left at the entrance. The object, found afterwards, became the reminder of a journey, the hint of a distortion. In Jung’s work, the noose is always tightening little by little around a system, and especially on oneself, so as to nurture a form of “pronoia”3 generating both meaning and the work in itself. The concretization of the piece comes only at the moment of the encounter with the other — the very first moment is never a result or the completion of the work, but rather the transitory beginning of a construction process. The absence of images generates other, mental ones, allowing the artist to question the labyrinths of realities constructed by our fragmented memories. The mixture of reality and fiction generates collateral damage impacting on the reality she is building. The artwork is the result of this process.

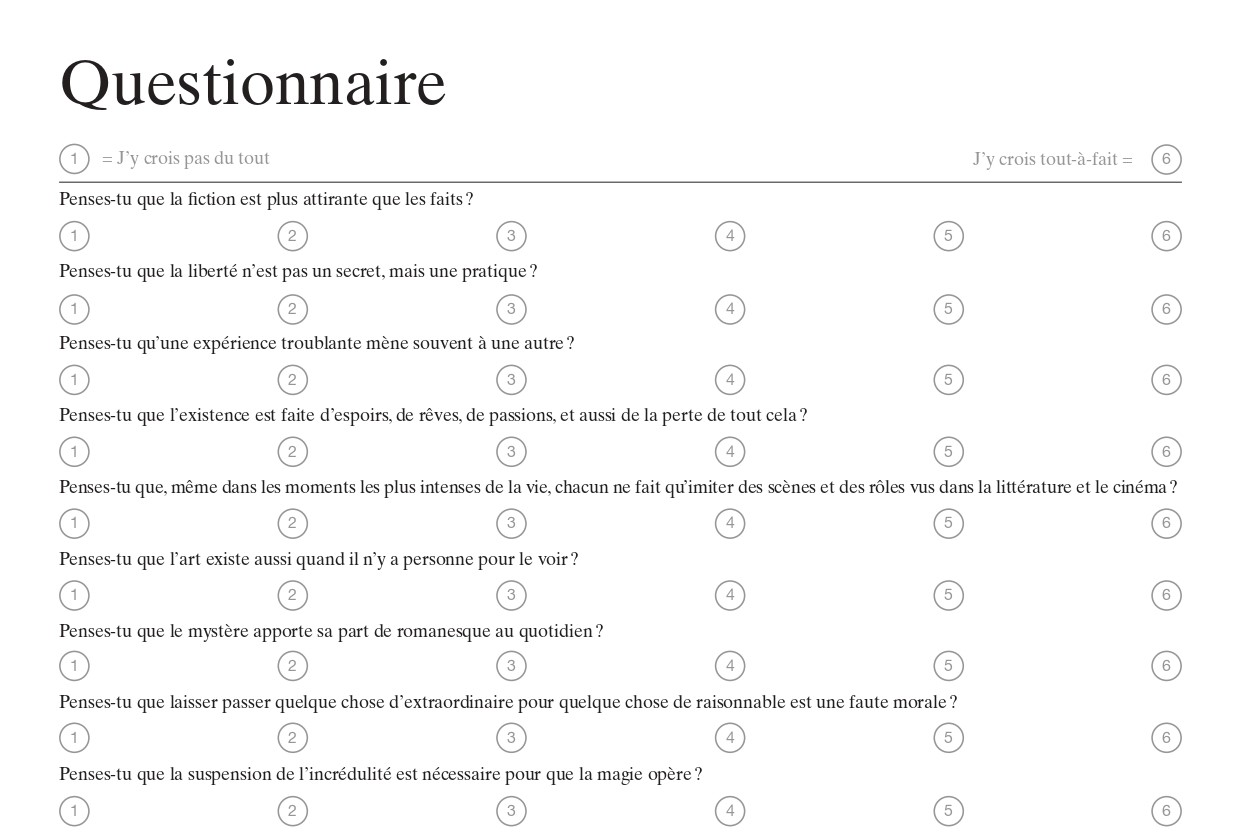

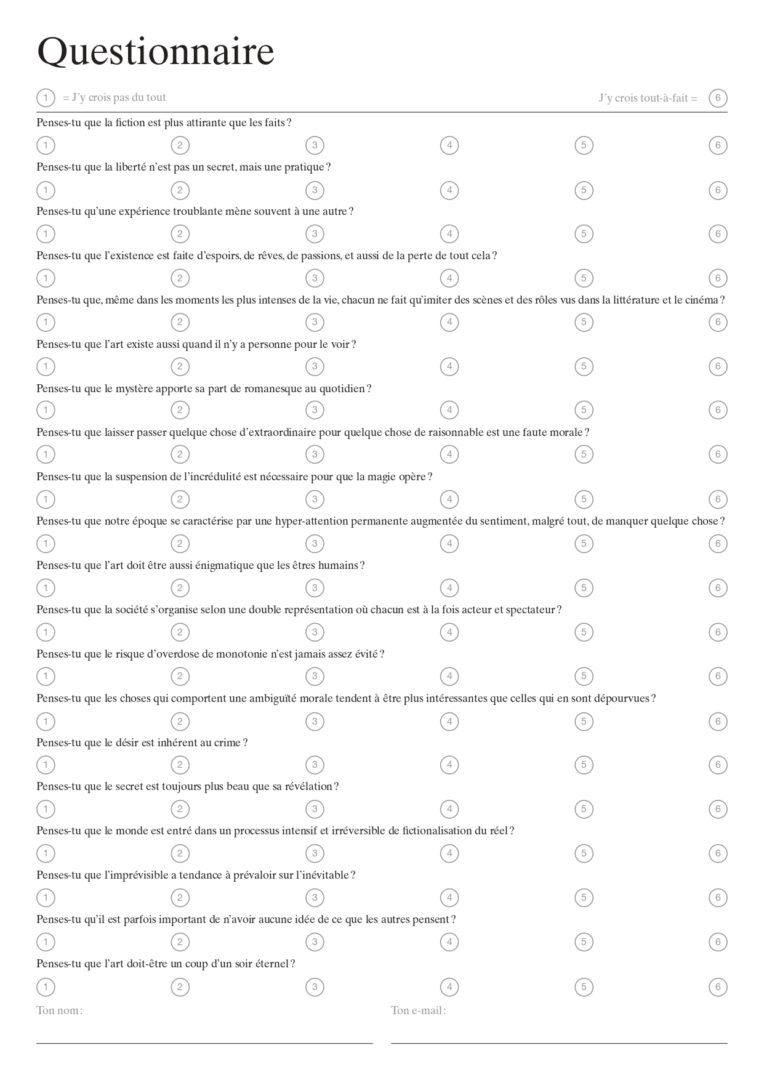

Among one of Jung’s earliest landmark moves, the coordination of a kidnapping at an exhibition opening at 22ruemuller in 2014 remains one of the most spectacular. Based on a self-representation instrumented by responses to a teasing questionnaire (“Do you think that fiction is more appealing than facts?” “Do you think that mystery brings romance to life?”, “Do you think that one interesting experience often leads to another?”), it thwarted the bolder spectators, who unknowingly embarked on a journey and a night deep into unknown countryside. Jung’s skillful diversion questioned the need for adventure that feeds on the mal de vivre and the desire to flee from reality. On site, there was nothing awaiting the group eager to detect the action of a performer in the slightest movement of the few people they were meeting that night. Jung’s work is accomplished in chance encounters, in a set of uncontrollable circumstances, as well as in emptiness, boredom and the unfulfilled search for the absolute.

Florence Jung uses art and its context as economic, societal and political microcosms. They serve to identify and highlight collective mechanisms such as the dissolution of the individual in enslavements fueled by suspicion and mistrust. As part of an invitation to the FRAC (Regional Contemporary Arts Fund) Lorraine in 2019, Jung had crossed different statistical studies to draw a portrait of the standard individual living in the French Grand Est region. The communication of all the criteria through classified ads which one could respond to – if one corresponded to them – questioned the very existence of this subject. The figure of Muller responded ad absurdum to the tyranny of the majority. It questioned a collective fragility: the vanity of wanting to measure the unquantifiable, and the stigmatization of our behaviors or our habits by the “objective” figures that govern us. Recently, at the New Galerie, in Paris, Jung’s exhibition “New Office” presented the archives of two years of activity of a parasitic company created by the artist. With New Office, the eponymous group, Florence Jung engaged in a process of data processing which replicated, on a micro-scale, the activity of data collecting and selling by companies such as Big Tech, but also the collective fear generated by these initiatives. The ads, divided into a dozen categories (sex, reality, otherness, nature…), were published on Instagram by New Office and pushed the audience members to communicate intimate elements about themselves while underlining the process of self-staging on social media. Echoing the transformation of the self into a commodity, as described by Eva Illouz4, New Office denounced the repercussions of late capitalism on our mental health, the saturation of affects and a system that makes the sensible world and the realization of the self an economic component. As a good observer of contemporary perversions, Jung makes visible the phenomena that she distorts. She proposes an emancipation which invites us to reflect on the way in which one can fill the intimate gap between oneself and one’s emotions, oneself and one’s representations, oneself and the others.

This reconciliation involves providing a space of imagination which will haunt the one who has met it for a long time. Never truly identifiable, the scenarios that Jung develops remain open and are inserted durably in the spectator’s reality and memory. From one of her next exhibitions, this summer, at the Biennale de Môtiers (Switzerland), we can expect the dissemination of the rumor generated by her new work to influence our representations again, and to question arbitrariness.

- “Other developments could have occurred, other revolutions, between other people in our place, with other names, other durations could have taken place, longer or shorter, other stories of forgetfulness, of vertical fall into oblivion, of sudden access to other memories, of other long nights, of endless love, or what have you.” in Marguerite Duras, Le ravissement de Lol V. Stein, Éditions Gallimard, Collection Folio, p.180. (Free translation)

- “Emancipation starts as soon as one questions the opposition between looking and taking action, once one understands that the very evidences structuring the relationships between saying, seeing and acting are part of the structure of domination and subjection. It starts once one understands that looking is also an act which confirms or transforms this distribution of positions.” in Jacques Rancière, Le Spectateur émancipé, La Fabrique Éditions, 2008, p. 19. (Free translation)

- A term indicating a form of positive paranoia, where the very idea of doubt would generate a feeling beneficial those experiencing that feeling.

- See, for instance, Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism, London: Polity Press, 2007.

- From the issue: 97

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Jill Magid at M Museum, Marc-Camille Chaimowicz at Wiels , Lucy Raven, Hanne Lippard, Matthew Angelo Harrison,

Related articles

Lyon Biennial

by Patrice Joly

Not Everything is Given, Whitney ISP, New York

by Warren Neidich

Rafaela Lopez at Forum Meyrin

by Guillaume Lasserre