VIRAL vs RIVAL

When blockchains and NFTs

contaminate the art world

During the 2010s, blockchain embodied the promise of restoring the original momentum of the Internet, before it was corrupted by the largest web companies and their so-called platform capitalism. Many analysts, who are disappointed by the evolution of the proprietary and authoritarian commercial web, have compared blockchain to an electronic agora, a registry based on decentralised protocols, democratic vectors of participation and emancipation for civil society. This peer-to-peer network structure did not require the intervention of any trusted third party (as are banks – if you think about cryptocurrencies). It was therefore tempting to see the resurgence of the pioneering Internet and its libertarian values of openness, free expression and sharing of space and data.

Blockchain technology is based on the transparency of the data exchanged, which cannot be deleted or falsified. Each member of the network has a copy of the transactions that take place on it, and can therefore check them and validate or invalidate them at any time using their own access key. On a practical level: blockchain thus facilitates the provision of computing power, the authentication of documents and data transformation chains, the assignment (and signature) of the roles of each project participant, as well as the generation of smart contracts that can automatically generate predefined actions.

However, since the early 2020, it seems that this “Internet of Value” embodied by the blockchain is being redeployed at the interface of new questions and new challenges: those of Internet governance, the ecology of networked relations or exchanges, and the creation of value. Little by little, value is becoming marketable again, in line with property rights, to the detriment of use value (by and for peers). So utopia would not have survived its commodification by the web giants? The question is not clear-cut, with analysts themselves hovering between emancipatory libertarian visions and positions and a shift towards neoliberal entrepreneurship.

Towards art ‘tokenization’?

Breaking through in 2021, the emergence of new cryptocurrency technology, NFTs or Non-Fungible Tokens, sent the cultural industries into a frenzy. This is illustrated by the impressive sales of Everydays: the First 5000 Days by the graphic designer Beeple at Christie’s for $69 million, or the first tweet by Jack Dorsey, co-founder of Twitter, for $2.9 billion. These feats have left many creators dreaming, while others have been more sceptical. The former see it as a major innovation for securing their intellectual property and safeguarding their rights as authors of digital works. The latter, on the contrary, see it as a new Trojan horse of unbridled capitalism in the cultural sphere and sound the alarm about its ecological impact.

These ambivalent interpretations, which alternate between a lively enthusiasm, often tinged with naivety, and a committed or amused resistance, make up the two intertwined and difficult to discern sides of the same reality.

Advocates of NFTs like to emphasise the traditional values of intellectual property. Within the registries secured by blockchain technology, the value of Non-Fungible Tokens is exclusively indexed to assets whose authenticity and rarity they simultaneously guarantee. By offering authors a guarantee of fair remuneration, they also provide reassurance to the markets and investors, who are up in arms against piracy. The days of Napster and P2P are over! Is this a return to digital property and financial speculation?

Several galleries made no mistake and created a new market for the purchase of virtual works. For the time being, it is up to all kinds of buyers to collect viral GIFs, Internet memes and other jpeg images of their choice. Based on new cryptocurrencies such as Ethereum or Tezos, which are more robust and “relatively” less energy-consuming than the old Bitcoin, various open (OpenSea – Rarible), participatory (Hic et Nunc) or closed-circuit platforms, after invitation and recommendation (Nifty Gateway, Foundation or SuperRare), are taking over these (online) transactions and guaranteeing their smooth operation. There is little art in the mass of images on these platforms. However, there are many viral culture icons, such as the famous Nyan Cat GIF, which sold at auction in February 2021 for $600,000 (the equivalent of just over half a million euros).

The introduction of NFTs thus creates artificial originality that lends a superior and exclusive value to the goods thus rarefied – which will nevertheless remain omnipresent on the Internet. In this context, by providing creators with an opportunity to apply a virtual signature to their digital works, NFTs guarantee continued originality and act as certificates of authenticity.

The history of art is full of such devices which, throughout history, have made it possible, in other forms and according to other conventions, to create and attest to the rarity of an item that can be reproduced. The value of a cast iron sculpture could thus be guaranteed, and its value increased by removing the mould used to make it. The destruction of photographic negatives has also made it possible to increase the value of numbered prints, which have become increasingly scarce. The “master” of a creative video, considered an original copy, acquired at a high price by a museum institution, does not in any way hinder its replication on DVD, sold at a much lower price by the same museum shop.

All of these conventions, arbitrary by their very nature, therefore made it possible to guarantee the fairest possible remuneration for creators while at the same time responding in two ways to the equilibrium of the market and the demands of collectors and institutions in the art world.

However, as with blockchain, whose integrity could be challenged, it may also be difficult to guarantee the absolute security of the NFT system so definitively. Is piracy excluded? Will counterfeiting be possible? While in theory this still seems unthinkable, many analysts are concerned.

(Un)doing the links, re-opening blockchain

In this discussion, the stance of artists remains ambivalent. Some attempt to benefit from the speculative bubble, sometimes with a touch of cynicism, by proposing a plethora of images on the marketplace, which are often quite unremarkable. Aware of the ephemeral nature of the potential financial windfall, they do not refrain from bidding higher. But the conditions for their business to be successful diminish over time. Once the initial record sales craze has passed, investor enthusiasm wanes as supply increases. From then on, a less naïve, sometimes more disenchanted, view of the situation emerges. Less blinded by the lure of gain, the artists demonstrate more reflexivity. Critical distancing then appears, which is reflected in several works, focussing on the ideology lurking behind NFTs and blockchain. Let us now consider three cases of aesthetic and critical questioning of this unique universe.

Antoine Schmitt

The artist and programmer Antoine Schmitt, a keen observer of “algorithmic modes of existence”, decided, for example, to delve beneath the surface of NFTs to de-code the programme operating in the background. An open-source enthusiast, he chose to invest in Hic et Nunc, the only platform that allows the integration of computer scripts in the same way as still or animated images. The artist submitted Buy me!, a work/programme that, strangely enough, seems to be able to ‘sell itself’. And indeed, it is an interactive and generative device that explores and implements the tactics of performative language to entice and enlist its potential purchaser.

The work uses a language of mental and emotional manipulation to convince the viewer to buy and collect it. From direct command to emotional blackmail, from pleading to simulated aggression, from clear request to implied wish, from guilt to false promises, from threat to lie, there are many ways in which someone can make someone else do something through pure language, whether in interpersonal relationships, advertising or the crafting of crowd consent. As a continuation of a previous work of mine Touch me!, Buy me! explores this dimension of performative language but in the context of NFTs.

Somewhat parodic, the artist’s gesture automates art and attempts to liberate the work. Another alleged effect of the NFT market is to free the artist from the yoke of intermediaries (galleries and other art dealers) by enabling a more direct relationship with collectors and potential art buyers. But here again, the promise of radical disintermediation is not the artists’ primary aim. Following the example of Antoine Schmitt, some dread having to act as a commercial agent in the art market. At the risk of losing their creative impetus and being forced, often to the detriment of their artistic practice, to play the role of entrepreneur.

When we deal directly with collectors, without an intermediary, we feel a bit like prostitutes without a procurer. We may have a special relationship with a wealthy collector, whom we can charm and pamper, or a deal with a relatively glamorous gallery owner who can introduce us to interested parties, but in the NFT market, we simply have to sell our charms directly.

Antoine Schmitt’s work pushes this capitalist or neoliberal logic to its extreme development, while foiling it. To be sold, his Buy me! work dispenses with any intermediary, but it also no longer requires the artist. As an artificial creature, obsessed with its promotion, the work is programmed to extrapolate all marketing strategies. Its autonomy makes it very combative and makes it a “living creature”: the immutability of the blockchain guarantees it eternal life. As the warning that accompanies the work states: “Beware, even if you buy it, it will keep trying to convince someone else to buy it, ad infinitum”. Is it therefore difficult to resist the dizzying grip of the market?

Jonas Lund

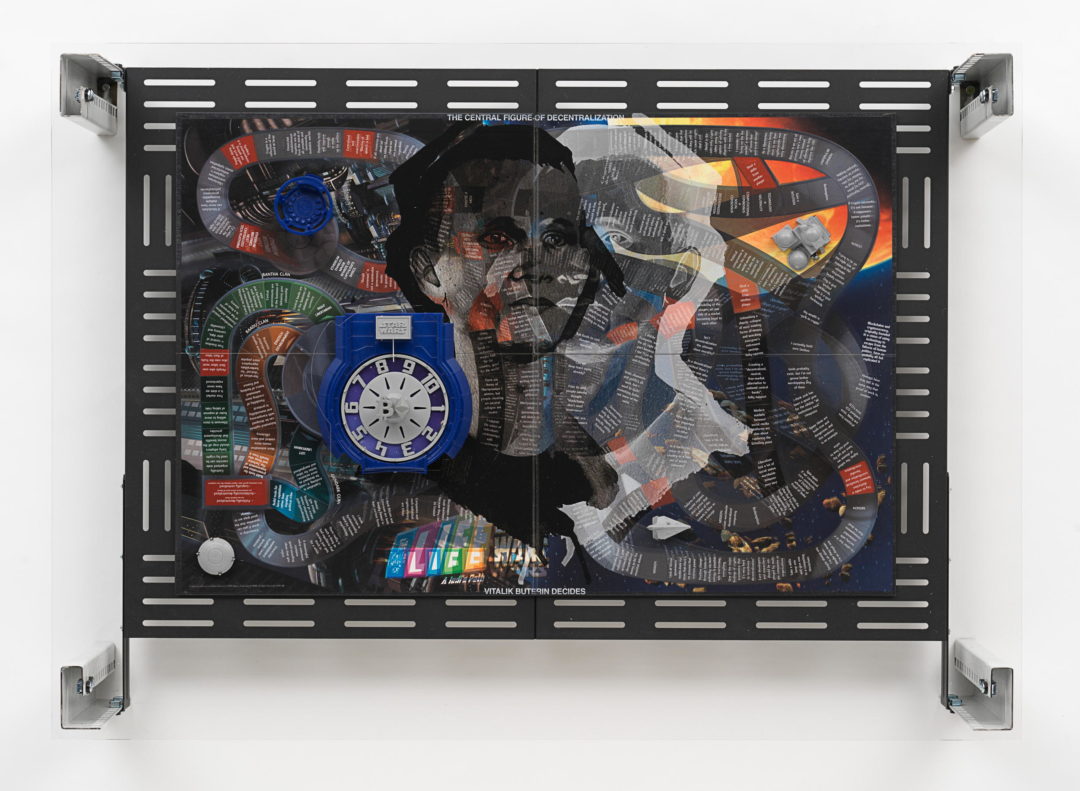

The artist Jonas Lund takes a more direct aim at the platforms that have a monopoly on NFT currencies. Because, ultimately, they are the ones who benefit the most from this new dematerialised economy. These platforms, which host the works and enable transactions, have all the possible qualities of a true art market intermediary, which intervenes between the artist and the collectors and other buyers. In particular, they charge artists for the use of blockchain, while at the same time instrumentalising and benefiting from their works by receiving commissions on sales to collectors. To avoid this grip, the artist Jonas Lund’s tactic was to create his own cryptocurrency: the Jonas Lund Token. This currency allows shareholders to invest in Jonas Lund’s artistic capital, giving them relative “power” over his practice. Via the Ethereum blockchain, the artist is thus open to speculation and invites the owners of Jonas Lund shares to join his board of directors. These shareholders, therefore, obtain the privilege of being consulted each time a strategic decision must be taken, relating to a project for new work, as well as to the artist’s participation in an exhibition or a conference. In this context, buying shares – Jonas Lund Token – means betting on the growth of the artist’s career. A career that is therefore subject to the market and the validation of shareholders, the focus of entrepreneurial and collective governance. The logic is that the more successful the artist’s career proves to be, the more valuable the Jonas Lund Token will be. Is this just another way for Jonas Lund to profit from financial speculation?

This tactical momentum is mirrored in other practices that have targeted the corporate world. A performance by the French artist Martin Le Chevallier, who literally presented his future as an artist to an auditing firm. Or the performances of the artist Julien Prévieuxwho, like Jonas Lund, subvert the tools of quantification and optimisation of work. In the field of cryptoart, let’s also think of the artist Kevin Abosch, who is often presented as a precursor in this field, creator of The Forever Rose in 2018, the “first” work whose exchange value in cryptocurrency – already christened “token” – had an independent existence solely on blockchain. Kevin Abosch asked himself: “What would happen, as an artist, if I were only reduced to a monetary value? I am a coin was inspired by this questioning, ironically and opportunistically highlighting the status of the artist as a possible commodity on blockchain.

Julian Oliver

In addition to the speculative excesses of cryptoart, there is also the environmental cost of NFTs, which are based on transactions whose security via blockchain involves energy-intensive calculations. In this respect, the “Harvest” project by engineer and artist Julian Oliver is exemplary. Linking a PC to a 2-metre wind turbine equipped with environmental sensors, “Harvest” launched a crypto-currency (in this case Zcash) mining programme whose efficiency may seem ironic and paradoxical given the energy unsustainability of blockchain technologies: the more the climate is disrupted, the stronger the wind, and the more money will be made from the mining to fund research on global warming. In this sense, “Harvest” fulfils the role of a whistle-blower, at the interface of art, ecology and political hacktivism, at a time when research is regularly obstructed, particularly in the United States under the climate-sceptic administration of the country’s former president.

Many other artists continue to invest in the world of blockchain and NFTs, without always fully understanding the ethical and political issues at stake, both within and outside the art world. Computer networks are social and political systems, in which blockchain protocols cannot ignore issues of governance and authority. In this respect, rather than turning digital capitalism against itself, the NFTs establish a new ownership economy, which is financially attractive but politically paradoxical. The tyranny of code or the obsession with traceability seems to be maximising capital and power once again: going hand in hand with the implementation of access keys and certifications that endorse a logic of rival appropriation of works that, on the contrary, favoured virality, transformation and sharing.

* Jean-Paul Fourmentraux, Doctor of Social Anthropology (PhD) is a Professor of Philosophy and Theories of Arts and Media at Aix-Marseille University. He directs research (HDR Sorbonne) at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) at the Centre Norbert-Elias (UMR-CNRS 8562). He is also a member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). His interdisciplinary work focuses on the political and anthropological issues of contemporary arts and technologies.

He is the author of the books Art et internet (CNRS, 2005, reprinted 2010), Artistes de laboratoire (Hermann, 2011), L’œuvre commune (Presses du réel, 2012), L’Œuvre virale. Net art and Hacker culture (La Lettre Volée, 2013), antiDATA, la désobéissance numérique (Presses du réel, 2020)

He has also edited the books L’Ère Post-media (Hermann, 2012), Art et Science (CNRS, 2012), Identités numériques (CNRS, 2015), Digital Stories (Hermann, 2016), Images Interactives (La Lettre Volée, 2017). These scientific articles are shared on Academia / Research Gate / Cairn / CNE.

1 The Bitcoin protocol and its eponymous currency, bitcoin with a lowercase “b”, were made public in 2009 under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, whose identity as an individual or group is still subject to speculation. t p.

2 On this point, see Fred Turner, Aux sources de l’utopie numérique, Paris, C&F éditions, 2012 (for the French translation), whose thinking has been extended in France by Dominique Cardon, La démocratie Internet, Paris, Presses de Sciences-Po, 2010. mens .

3 See, for example, Dadiani Fine Art Gallery in London : dadianifineart.com

4 Cf. Moulin Raymonde, ‘La genèse de la rareté artistique’, Ethnologie française 8/2-3, March-September 1978, pp. 241-258.

5In this regard, see Grégory Chatonsky, L’art critique des NFT, 2022: http://chatonsky.net/nft-critique/

6 For a critical mapping of blockchain, see Louise Drulhe’s video collage, Blockchain, an architecture of control? 15min, 2016. In it, the French artist reveals how, in opposition to the old web that had become hierarchical and centralised, the blockchain first embodied the utopia of a shared space before being unveiled by liberalism and embodying a new, authoritarian form of control architecture. n re nd bs d êybdr https://vimeo.com/165589644

7 Antoine Schmitt, Buy me! i), 2021: https://www.antoineschmitt.com/buy-me-fr/. Interactive and generative NFTgf, edition of 6 copies for sale on the TEIA platform : https://teia.art/objkt/620428

8 Antoine Schmitt, Touch me!, 1999: https://www.antoineschmitt.com/touche-moi-fr/. Screen saver: words-pictures, random and learning algorithm.dnlde.

9 Martin Le Chevallier, L’audit. Processus de consulting, 2008: http://www.martinlechevallier.net/audit.html

10 Julien Prévieux, https://www.previeux.net

11 Kevin Abosch, The Forever Rose, http://www.foreverrose.io/#/—, 2018.

12 Kevin Abosch, I am a coin, https://iamacoin.com, 2018.

13 Julian Oliver, Harvest, https://julianoliver.com/output/harvest, 2017.

14 Sur ce point voir les œuvres de Simon Denny, https://simondenny.net, https://www.zerodeux.fr/interviews/simon-denny/; ainsi que la cartographie politique du Net proposée par Louise Drulhe, L’atlas critique d’Internet, 2015 : https://louisedrulhe.fr/internet-atlas/

Head Image : Antoine Schmitt, Buy me!

Related articles

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret

An exploration of Cnap’s recent acquisitions

by Vanessa Morisset