Under the Eye of May ‘68

Contemporary Art’s Critical and Political (Im)possibilities

Every decade, for half a century, the events of May-June ’68 in France have been the subject of many publications and exhibitions. One of the original historiographical features of that year’s demonstrations and goings-on has to do with the in-depth revisitation of the involvement of visual artists in the movement, and their careers during the “’68 years”.1

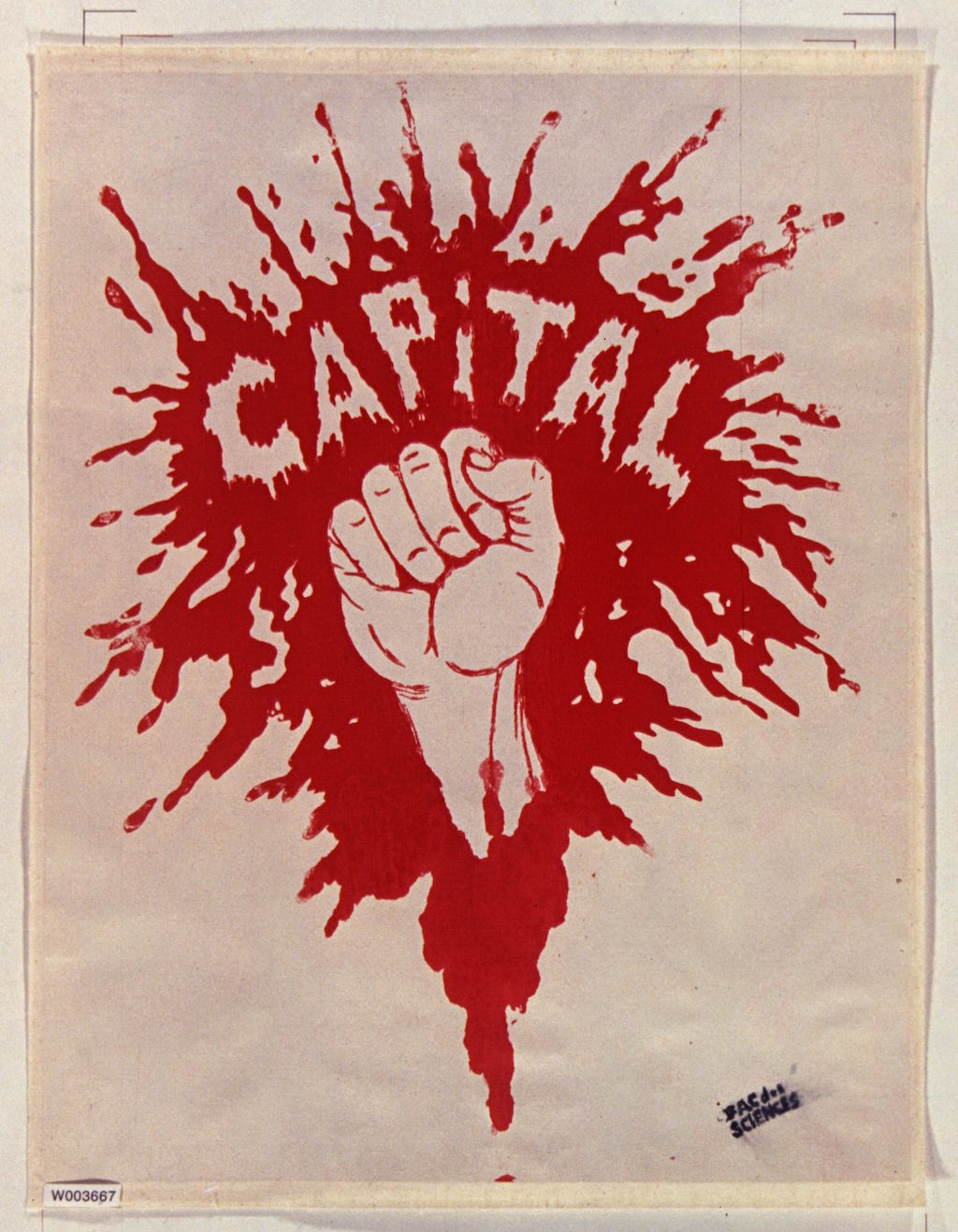

The main episodes of that history are well-known. On 8 May, at the instigation of student architects, a strike committee was set up in the Paris School of Fine Arts. The students were joined by members of different political groups already active in the social movement, and by a few artists from the Salon de la Jeune Peinture, like Gilles Aillaud, Eduardo Arroyo, Francis Biras, Pierre Buraglio, Henri Cueco, Lucien Fleury, Gérard Fromanger, Merri Jolivet, Julio Le Parc (and the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel aka GRAV), Bernard Rancillac, Gérard Tisserand and Christian Zeimert. A week later, a first lithograph poster was printed in an edition of thirty. It was planned to sell them in a gallery that supported the ongoing struggle, but after covering just a few feet in the street, they were grabbed by students and stuck on walls. They were not put on sale for two months. On that same day, a silkscreen printing workshop was set up by Guy de Rougement and Eric Seydoux to increase the quantities. The Atelier populaire [Popular Workshop] of the School of Fine Arts was born. More than 500 posters were produced in just a few weeks and about a million copies in all were distributed.

Every night poster projects were submitted to be voted on at a general meeting. In the School of Decorative Arts a similar workshop was set up on 29 May, its members closer to the Communists than those of the School of Fine Arts, where Maoists held sway. Other comparable programmes were prepared at the Faculty of Medicine and the Faculty of Science, in Paris and also in the provinces. From 20 May onward, recognized artists such as Pierre Alechinsky, Leonardo Cremonini, Jean Hélion, Asger Jorn, Roberto Matta, Gina Pellon, Paul Rebeyrolle and Antonio Ségui also worked on posters at the School of Fine Arts alongside the Atelier populaire. But on 27 June, at four o’clock in the morning, the place was raided by the security police, and subsequently closed.2

Nowadays, the adventure incarnated by those workshops seems remote and improbable. This is why it offers a good way of gauging the changes which affected relations between visual artists and politics, in particular with its anti-capitalist and revolutionary tendencies, whose expression, fifty years ago, seemed pivotal, even if related to a minority.

From the popular workshops to integrated art criticism

Beyond the posters’ content which was often overtly critical of the capitalist system, a dissatisfaction with the art market and art institutions was also being voiced. It was marked by the almost systematic absence of any signature and a rejection of authorship, through the distribution of works outside galleries, museums and other art circuits, through a joint effort involving other social groups such as students and then, in some instances, workers in the years that followed, and by the fact of artists being subject to democratic assemblies and, last of all, by the combination of these factors with the use of technologies which were then relatively new in France, like silkscreen printing. Taken individually, each one of these features could be found in the most critical and utopian art of the ensuing decades. There is no shortage of artists’ collectives today, some of which challenge individual authorship and intellectual property.3 Alternative circuits for distributing art have grown in number on the sidelines of the market and public institutions. Documentary and militant investigations in social worlds which are extremely alien to art are crucial raw material in contemporary works. As far as new technologies are concerned, there is little point in mentioning that they regularly inform new art practices.

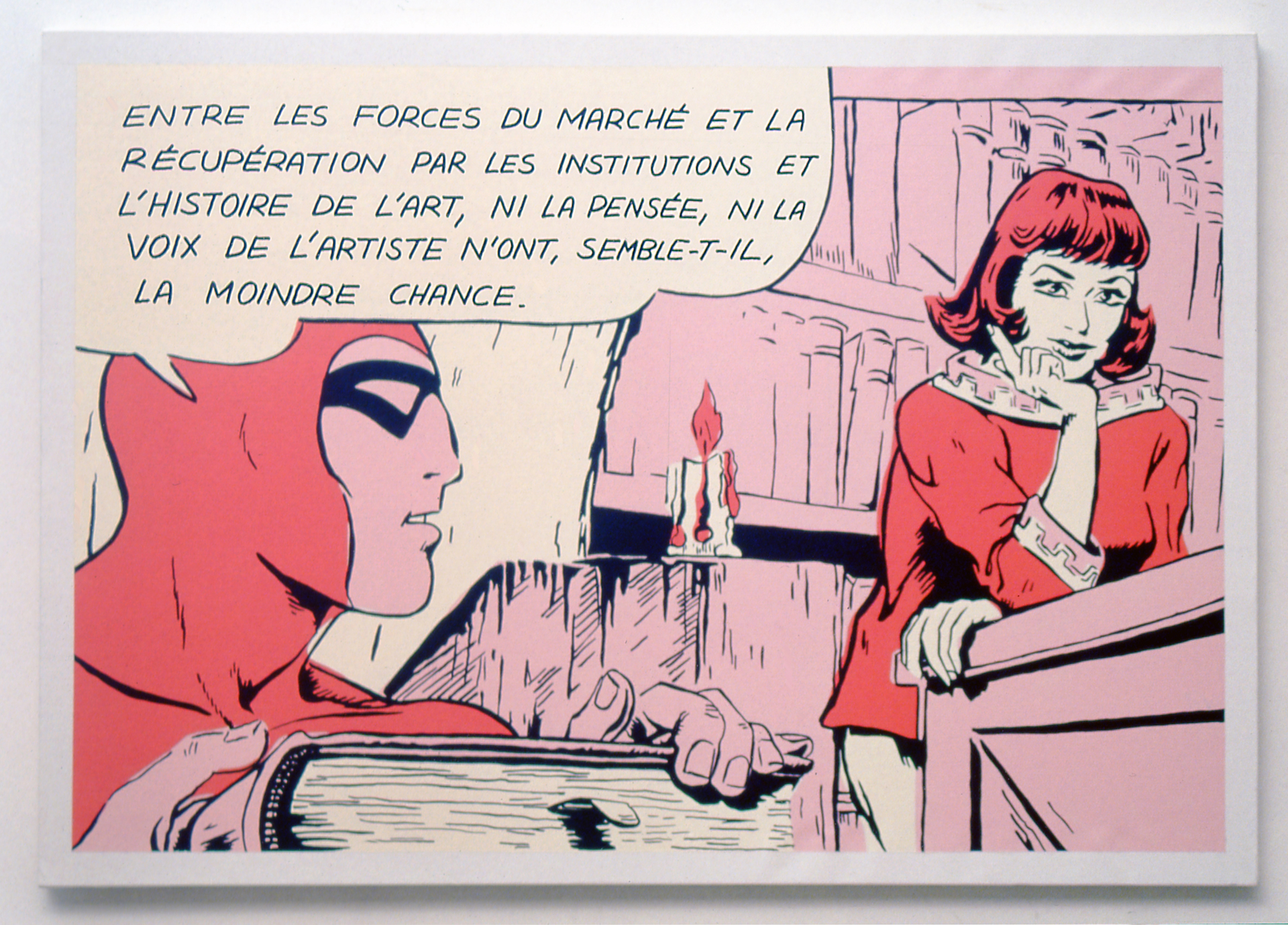

Art Keller, Les forces du marché. Série le crâne d’argent, 1994. Acrylic on canvas, 65 × 100 cm.

Collection Yoon-Ja & Paul Devautour MAMCO – inv. 1994-725

If the strategies which came to the fore in the popular workshops of May ’68 were thus not absent from the art world which followed, their combination and their existence over time came up, on the contrary, against serious obstacles. Much changed by the events, and seeking a new style, the artists involved in the Atelier populaire almost all reverted to painting in the early 1980s, not without previously trying their hand at many other forms of artistic and political engagement, including abandoning art and working in factories, as in the case of Pierre Buraglio and Jean-Pierre Pincemin.4 The history of the popular workshops may well have been fleeting and probably unimportant, but it still harbingered the art world’s capacity of resistance to those criticizing its usual standards of operation.

All forms of criticism, including fierce critiques of the artistic microcosm and institutions, and (almost) all radical political discourse,5 have managed, for the past fifty years, to find a place in this world, by way of works and arguments, in galleries, biennials and museums. Contemporary art tones down and retrieves all manner of content, even—in certain situations which would benefit from closer definition (economic and financial crises?)—turning criticism of merchandise, spectacle and capitalism into distinctive artistic merchandise, if ever there was. As for those artists who try to disappear by more or less totally turning their back on things material and traces, visibility, exposure and signature (through anonymity and heteronymy), by asserting their ready-made character, and abandoning all creative work, in some cases even by committing suicide,6 they likewise end up by occupying a niche in contemporary art history.

Some theoreticians have seen in such developments the symptom of a death of the historical avant-gardes which sought to go beyond art in the construction of forms of emancipated life. Others make this admitted and inoffensive hyper-critique of contemporary art the corollary of its growing heteronymy and its definitive subordination to economics and capital.7 In the last two decades, the strategic place of art in the financial, fashion and luxury industries has undoubtedly bolstered this feeling. Many people involved in the art world share these analyses while continuing to defend their environment as an at least virtual refuge for freedom of expression and a potential factory of alternative life forms and novel gestures within political configurations in which these attitudes are being increasingly devalued, put into perspective and repressed, and confronted by art for art’s sake which still dominates artistic output. Whatever the case may be, critical art (criticizing art, economics, society and politics) has, in the last half-century, become a thoroughly well established arena in the artistic domain. Does this mean we should give up hope in artists’ abilities to transform the rules of artistic play, and have some political clout beyond their own world?

Novel upheavals and fragmentations of art

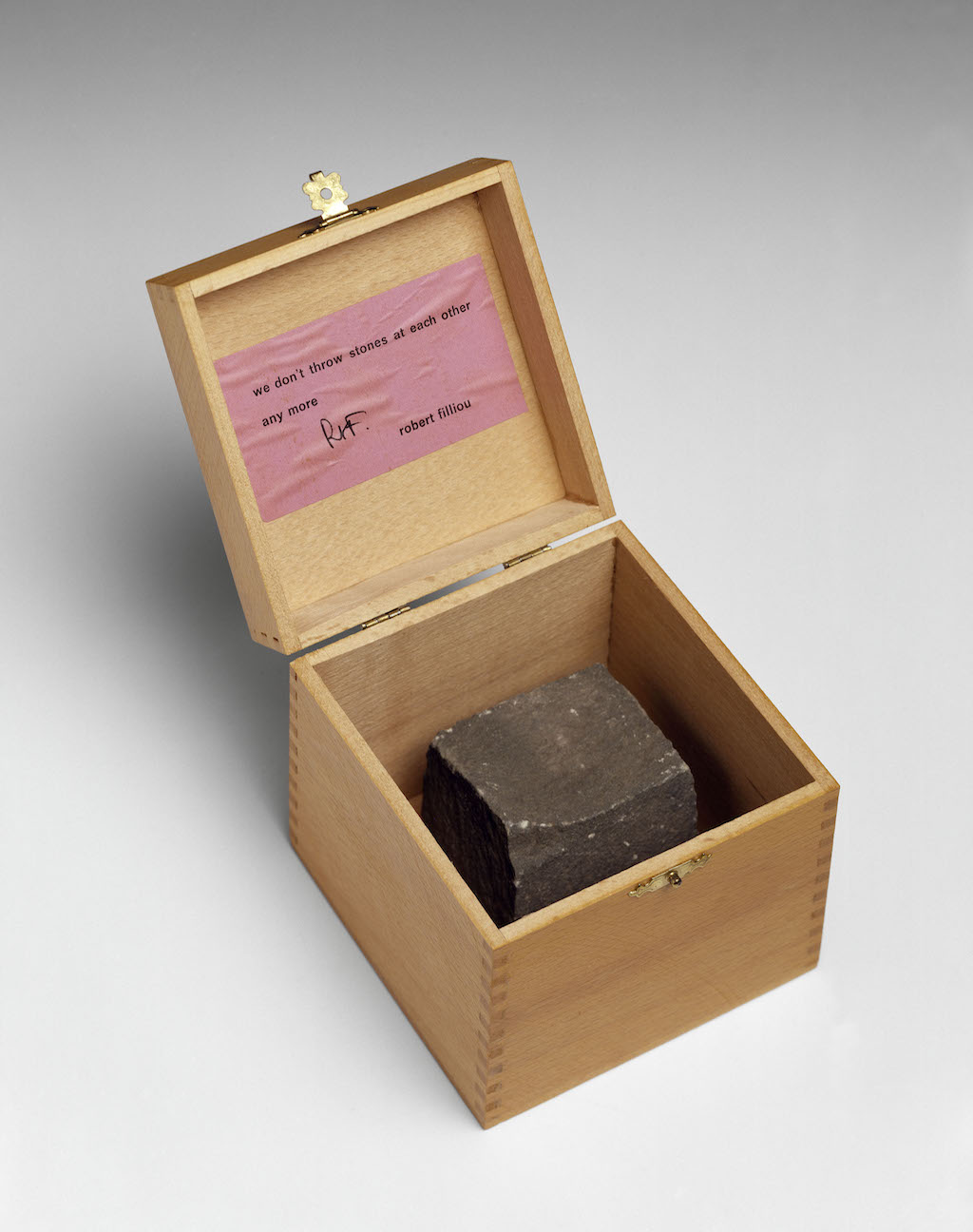

Robert Filiou, Optimistic Box n°1, 1968. © Marianne Filliou Paris, Centre Pompidou – Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle Photo : © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Georges Meguerditchian.

Before giving in to melancholy and pessimism, it is worth tightening up our analysis in its socio-economic aspect. Today’s art world, its morphology and its place in society, have nothing to do with what they were in 1968, when the very term “contemporary art” did not yet exist. It is hard to understand the broad and swift incorporation of the most diverse of contents and critical forms within today’s art without observing the extraordinary demographic and geographic spread of artistic worlds over the past fifty years. The number of visual artists has risen considerably, as has the number of galleries, biennials, exhibitions and museums, at the same time as art institutions have become internationalized.8 The diversification of artistic supply, its themes, its forms and its different shades, is a mechanical consequence of the growth of these worlds and the competitiveness within them. This explosion, which has been far more vertiginous in the last twenty years than in the preceding century9—and which we are still having trouble gauging in any precise way—, has gone hand-in-hand with a massive rise both in the demand for artworks and in the capital sums invested and consumed in the visual arts.

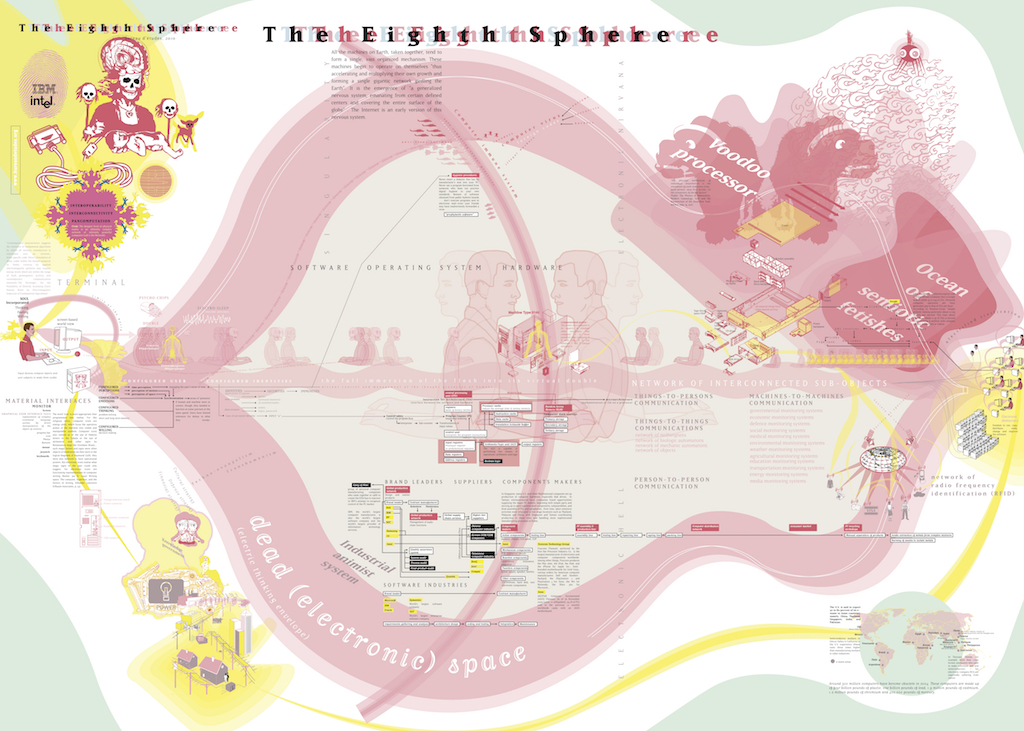

This extremely rapid expansion of the scale of the art world has been accompanied by a multiplication of disciplines, styles and conventions, otherwise put, by a creeping ‘Babelization’. In each one of the sub-worlds which thus today form the sundered continent of contemporary art, the society of artists is extraordinarily layered: the degree of concentration of incomes and reputations is higher than in most other professions, as is the rate of financial precariousness and the number of people with several activities. At the opposite end of the high ground where collectors and superstar artists gravitate, the fringes and sidelines of the market are multiplying. The ongoing ferment of criticism is benefitting from this; and gallery owners and curators are tapping into it. Because the new space of art is leaning on an institutional system undergoing far-reaching changes in relation to what it was fifty years back, when the dealer and the critic together played a central part in the building of careers and reputations. Alongside museums and auction houses, whose number and importance are on the rise, collectors and curators are also contributing to the production of the aesthetic and economic value of artworks. Far from having become that unified world, levelled out by capitalism and merchandise, contemporary art, through its very economic inspection, appears on the contrary increasingly like a differentiated, fragmented, layered space: a colourful, patched up fabric which contains many stitches and many different gaps.

Gianni Motti, Je vous avais dit que je n’allais pas très bien, Cimetière des Rois, Genève. Translated from the gaelic inscription on the tombstone of Spike Milligan, dead in 2002. © Yann Forget / Wikimedia Commons

The situation is paradoxical: these boundaries, between artists, between artists and institutions, and between dealers and non-dealers, offer in principle many more footholds than existed in the “’68 years” to develop an art which questions the norms of art, or opposes them. The direct political involvement of artists and works with a political content have certainly not disappeared: their number, if not their proportion, has undoubtedly increased in the last few decades. But beside them, a set of strategies turned towards the art world itself is deconstructing its foundations, thus rendering more complex the relations between art and political criticism.

Resistances

It can be said, in a schematic way, that two major traditions have dominated the stage of this art that is critical of art for half a century: conceptual and neo-conceptual art, and institutional critique.10 The former claims to withstand the grip of exchange value. The latter speaks out against or, better still, undoes the instruments of valorization. With the spread of art intermediaries and go-betweens, new forms of institutional critique aimed at curators, art centres and schools (there has been talk of an ‘educational turn’) are developing, well beyond those which focused just on museums and their ramifications in the world of multinationals and authoritarian regimes, as was the case in the 1970s. The goal of collective arrangements, such as the Nouveaux commanditaires [New Patrons] in France, is for example to free artists, at least temporarily, from commercial restrictions by intensifying the link between the work and the public.11 Other forms of resistance are expressed by evanescence (performance, so-called relational aesthetics) and dispersal (multiples, fanzines, ephemerae), by mapping and archives, by market and museum simulation, and the like: through a set of strategies and forms aimed at restoring and disseminating the use value of works and lessening, delaying or even recovering the expression of their exchange value. Rather than renewing a molar vision of the limitations imposed by the art world on aims of emancipation, as in 1968, for some decades now art that is critical of art has been developing molecular strategies which are local and buried in the countless folds of the artistic milieu.

For others, the sole radical political outlet for artists does not lie in criticism of the art system (in the hope of reforming and transforming it), but in getting out of the art world, no longer to disappear, this time, as might have been imagined in the previous period, not only in order to boycott large international events (such as, recently, the Biennials in Istanbul, St. Petersburg, Sydney and São Paulo, between 2013 and 2015), but to operate mainly in other social worlds—business, politics, international relations, hospitals, schools, science and technology, the digital sector, etc.—with critical techniques accumulated throughout history by artists. Rather than turning the social goal of art towards art itself: transforming other practices, completely altering other institutions. Rather than investigating other worlds and making them visible within art institutions: shifting contemporary art practices to terrain that is alien to them, transforming the desire for defection into active exteriority, and intensifying forms of protest in spheres other than art.

Is it at this price that liaisons might emerge with other social groups, comparable to those imagined by the artists of the May ’68 popular workshops with students, workers, and peasants? A theoretical and political paradigm unified all those hopes, as well as the criticisms hailing from the art world fifty years ago: anti-capitalism, and its corollary, the identification of the artist with the worker (as in the Art Workers Coalition founded in 1969). In this frame of thought, local criticism of norms and art institutions remained indissociable from a global criticism of economic exploitation. In the past few years, the theme of precariat has provided the stuff for a rekindling of this short-circuit between art politics and general politics. But resistance to its adoption remains strong—there is cause to doubt whether it will win over artists and offer creative material.

In fifty years, critical art is not dead, even if it has relegated what it retained in terms of revolutionary messianism to the rank of an aesthetic element. One lesson from the May ’68 popular workshops does however live on: when art intends to withstand commercial institutions while at the same time opening up new political possibilities, it must act outside the art world.

1 Philippe Artières, Éric de Chassey (eds.), Images en luttes. La culture visuelle de l’extrême-gauche en France (1968-1974), Beaux-Arts de Paris éditions, 2018.

2 For a description of these events, see, among others, Jean-Louis Violeau, “L’expérience 68, peinture et architecture entre effacements et disparitions”, in Dominique Dammame, Boris Gobille, Frédérique Matonti, Bernard Pudal, Mai-Juin 1968, Éditions de l’Atelier, 2008, p. 222-233 ; Les affiches de mai 68, Beaux-Arts de Paris éditions / Musée des beaux-arts de Dole, 2008. On the connections between French critical theoreticians and narrative figuration, see Sarah Wilson, The Visual World of French Theory:Figurations, Yale University Press, 2010.

3 On the development of these strategies of collective authority, see in particular Blake Stimson, Gregory Sholette (eds.), Collectivism After Modernism, University of Minnesota Press, 2007 ; Jacopo Galimberti, Individuals against Individualism: Art Collectives in Western Europe (1956-1969), Liverpool University Press, 2017.

4 Éric de Chassey, Après la fin. Suspensions et reprises de la peinture dans les années 1960 et 1970, Paris, Klincksieck, 2017.

5 We should question the existence (and the possible forms) of a far right contemporary art, overtly racist and neo-fascist, as exists in literature and film.

6 May I humbly refer readers to Laurent Jeanpierre, “Faire de sa mort une œuvre d’art. Une pédagogie cynique ?”, art press 2, 3, “Cynisme et art contemporain”, Nov.-Dec.-January 2006-7, p. 16-27.

7 Among many works developing such theses, let us mention one of the most recent, Julian Stallabrass, Art Incorporated: The Story of Contemporary Art, Oxford University Press, 2004.

8 We must here mention the pioneering works of Raymonde Moulin, Le Marché de l’art. Mondialisation et nouvelles technologies, Paris, Flammarion, 2003.

9 Clare McAndrew, Suhail Malik, Gerald Nestler, “Plotting the art market: An interview with Clare McAndrew”, Finance and Society, vol. 2, n°2, 2016, p. 151-167.

10 See the excellent essay by Olivier Quintyn, Valences de l’avant-garde, Paris, Questions théoriques, coll. Saggio Casino piccolo, 2015.

11 François Hers, Xavier Douroux, Art Without Capitalism (2011), Les presses du réel, 2013.

(Image en une : Christoph Büchel, Dump, Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view of « Superdome », Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2008. Photo : Didier Barroso. Courtesy Christoph Büchel ; Hauser & Wirth Zürich, Londres).

Related articles

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret