TV Resists

In his 2009 biography of Marshall McLuhan, the writer Douglas Coupland comes up with the following witty words: “Why isn’t the TV ‘medium’? Because it’s rarely ‘well done’.”1 Without wanting to be a killjoy, it is also altogether possible to take the witticism literally. In the mediasphere we are living in, the TV is actually not medium: it can be cooked in various ways. Co-existing with other media, it is part of a technological layering where many different media platforms are overlaid and dovetailed. So television is presented to us as a medium—one medium among others in the post-medium age.2 This observation has, when all is said and done, become somewhat commonplace, but it nevertheless twists a teleological understanding that is frequent in the field of media studies which, up until the end of the 1990s, tended to turn every new “optical medium”3 into the Hegelian cannibal devouring the previous ones. If the technicist naivety of the uni-medium and the super-medium is no longer common currency these days, what should surprise us is thus not so much that the arrival of the Internet has not banished the other media from the playing field, but rather the survival of one of them.

It has to be said that, at least in our elected area of observation—France’s present-day art scene—, television is putting up resistance. After the summer, Benjamin Valenza invited artists, musicians, theoreticians and poets to bolster Labor Zero Labor, an “artists’ medium” whose shooting set installed at La Friche la Belle de Mai in Marseille was extended by a streaming website. Then this winter, the exhibition “JUMP” at the Brétigny Contemporary Art Centre, curated by Céline Poulin, broadened the spectrum with a group show in which most of the installations in fact opened up autonomous dissemination systems—with the opening, incidentally, broadcast live on the art centre’s website. The golden age of television is no more, and yet it remains a reference, a formal reservoir and a tool working for artists. What is it, in TV, that goes beyond the viewing of moving images, over which it no longer has a monopoly? What is the surplus value that justifies talking about a comeback of the medium?

Artists and television in the digital age: a Frankenstein effect?

First and foremost, let us specify that the fact of wearing art glasses to examine the phenomenon has a certain effect on what is at stake. Most media theoreticians have focused on the phenomena of reception and use, as such inheriting the legacy of Marshall McLuhan, much of whose analytical system is based on a distinction between hot media and cold media, made on the basis of the quality of participation introduced.4 The fact is that in the field of art, the issue of production is just as significant as that of reception. In an age where television still assumed the position of a great global medium, dreaming of being a television producer was a way of subverting the system from within. Henceforth obsolete and losing its social meaning, continuing to want to play that part when it is perfectly possible to get away from it, has perforce to do with more complex motives. For Will Benedict, currently busily preparing two new post-documentary fictions which extend his first video, Toilet Not Temples (2014), it is indeed because the golden age of television is behind us that it becomes possible to hijack its codes, and appropriate them. For his part, he sticks with the system of TV news and the embedding of one image in another image, where there is a juxtaposition of the space/time-frames of the studio programme presenter and the reporter in the field. A procedure of truth well rooted in perceptive habits, and as such, the ideal terrain for sowing the virus of fiction—with nobody being especially surprised that TV presenters look like whales or dolphins.

However, does this Frankenstein effect necessarily go hand in hand with a nostalgic stance? For the philosopher Mark Alizart, it is in fact possible to read in this way of looking back at things a buffer-like modus operandi with the upheavals brought on by the de-materialization of the digital signal. At the very least, this apprehension exists in the field of thought, as is analyzed by his next book Informatique Céleste, dealing with cybernetic thinking and its non-reception among French intellectuals: “In philosophy in France, there is a huge difficulty in thinking computer-wise. The way I see it, this comes from way back: when it emerged in the 1950s, the theory of information, and even more so of cybernetics, was perceived like a comet’s tail of mechanistic thinking, and thus violently rejected. In relation to the return to television among certain artists, I cannot stop myself from thinking that there is also a certain form of nostalgia mixed with apprehension in the face of the world in the offing. Which is to say that even in the place where this is being de-materialized, we are all the same much more at ease with a signal that looks like something living than with a totally de-materialized signal.”

Virgile Fraisse’s shooting of Pragmatic Chaos, prod. Labor Zero Labor, Triangle France, 2016. Photo: Virgile Fraisse

In 2010-2011, the group show “Are You Ready For TV” at the MACBA in Barcelona also fitted the medium into an achronic relation. The undertaking was ambitious: drawing up a sweeping overview of the relations between art and television between 1960 and 2010, and up until today, in order to give the medium a history of art. Faced with the immensity of the task, the curator Chus Martínez explained that she had followed a second thematic thread in her approach, basing her selection on works “outside time”. These works, by artists as diverse as Dara Birnbaum, Chris Burden, Jef Cornelis, Guy Debord, Harun Farocki, Alexander Kluge, David Lamelas, Richard Serra, Bill Viola and Andy Warhol, presented, according to her, the following common feature: “These ways of re-imagining the world were from the outset conceived to be radically different from their day and age.”5 This imaginary outside-time factor, making television one of those “non-places” of super-modernity dear to the anthropologist Marc Augé,6 nevertheless seems to still belong to the old paradigm of television as an operative global medium. So for these artists, hewing out a utopian –and atopic—space within it linked back up again with a form of minimal activism, and a refusal of the established order valid as a result of its simply taking its distance.

The project-space will be televised: a collective and multifacted economy of production

Six years later, the setting has definitely changed. In the present-day dispersal of the digital flux, setting up an A-to-Z broadcasting channel becomes not only a way of generating a concentration of content and production, which has been lacking, but also of inventing a tool making it possible to grasp reality, and create a situation. Rather than talk in terms of essence, which ushers in the nostalgic stance, it is thus necessary to focus on use. At La Friche la Belle de Mai, Benjamin Valenza thus launched Labor Zero Labor, a television station whose content filmed in the studio on the spot is broadcast live on the Internet. For him, “it was a matter of not making a simple TV-website, at the risk of tumbling into a parody of the Telethon or weather reports. Keeping a political dimension was essential, and in tune with the projects of the 1990s such as the telestreet movement, close to thinkers such as Franco Berardi and Antonio Negri”. Launched during Art-O-Rama over the last weekend in August of this year, Labor Zero Labor came into being from an invitation made by Céline Kopp, curator of Triangle. “Rather than a solo show, I preferred to make the most of things to set up a collaborative and informative medium managed by artists”, explains Benjamin Valenza. “In 2014, I started to ask myself about live broadcasts in relation to my performance activities, first of all with a view to producing myself the documentation of my pieces. Then, in collaboration with Lili Reynaud-Dewar, we came up with a televised programme around performance called Performance Proletarians!!!. For a weekend at Le Magasin in Grenoble, we brought together fifteen artists and broadcast 36 hours live. With Labor Zero labor, I was keen to open up to other spheres, and include fiction in particular. Even if the project is hosted by an institution, which made it all possible through its logistical capacity, I never conceived it as an exhibition. The medium will go on existing. For the time being, we’re starting out with a two-year time-frame, based on five hours live per month.”

Regarding television as a work situation, both collective and experimental, also recurs in the argument put forward by Benjamin Thorel. This art critic and curator is also the author of L’art contemporain et la télévision (2007), and contributes to Labor Zero Labor with a series of talk-shows called Tell’N’Talk.7 For him, being interested in television was first of all a way of getting away from the hyper-essentialization of the video medium and its formalist dead ends. He also reminds us that “since the 1960s and 1970s, and Nam June Paik, who cobbled together more than a few machines and invented circuits for both distribution and creation, the television motif has made it possible to shift the stakes. In relation to video art, it makes it possible to not stay confined within strict issues and the often essentialist readings of video art. Television is above all a tool, which applies different ways of working and acting on reality.” In fact, the fast production line and the immediacy of the live event are akin to the working situations of performance and the television programme. Further still, the collective and Jack-of-all-trades organization implied by this latter, a fortiori in the case of an artist’s medium, is, according to Benjamin Valenza, similar to the management of a project-space, which also involves “writing theoretical texts as much as sweeping things clean” (he himself being one of the founders of the 1m3 space in Lausanne).

Dennis Rudolph, The Saturday Night Live, view of the exhibition «JUMP», CAC Brétigny, 2016. Courtesy Dennis Rudolph ; galerie Lily Robert.

With Dennis Rudolph, invited by Céline Poulin as part of “JUMP”, we find the three terms of the equation. He also comes to the television exercise by way of performance, and is also the founder of the State of the Art space in Berlin. At the CAC Brétigny, he is presenting the installation Saturday Night Live, showing the décor and wings of the American talk-show of the same name. After an initial episode in California, his early intention was to invite onto the set Middle Eastern artists and activists. But the whole episode would deal with the implosion of the very talk-show concept: the artist finds himself alone on the set, condemned to himself play the parts of interviewer and interviewee. An at once bitter-sweet, and farcical, way of staging the contradictions of the mass media, where the potential audience is six billion people, but where everyone is often content to soliloquize in his own corner.

Globality, attention and interactivity: what do artists’ media dream of?

Nevertheless, raising the television issue must beware of not disqualifying the utopias of its golden age in the guise of them stemming from nostalgia. In the age of dispersal, the fantasy of the great global medium precisely has all its reasons for being: not for returning to a past situation, but for trying to reconcile the advantages of both horizons. It is not solely at the level of the production circuit exceeding the individual that this ideal of the collective intervenes, or, to echo Henry Jenkins’s words, “the culture of convergence”:8 “Now that the Internet has settled the matter of access, the very contemporary problem of attention arises. But this new situation of address does not seem to me to be necessarily more democratic, because it is still necessary to sort things out among the infinite choice. Bertolt Brecht made radio into a revolutionary medium because, potentially, everyone can become a transmitter. With the Internet, the material possibility is indeed there, but in terms of relation, the post-Trump age has above all materialized the informational bubbles in which we confine ourselves”, Benjamin Thorel suggests.

The great difference with present-day media layering is the possibility of re-coding situations of monopolistic declaration, in a quasi-immediate way and with a potentially similar public.

This is precisely the starting point of Pragmatic Chaos, Virgile Fraisse’s fiction broadcast on Labor Zero Labor. The name comes from the same-name algorithm developed after a competition held in 2009 by the giant of video content distribution, Netflix, to improve its existing system of film suggestions. Each of the co-written episodes brings in a specialist to examine the impact of the data classification systems on everyone’s choice. In Prédiction/Production, likewise, the Netflix war machine formed the heart of the matter, because the video, made during a residency at Triangle that same year, tried to make up for the mysteries preceding the announcement of the release of the series Marseille, produced by the American company. The characters re-interpreted and re-contextualized passages borrowed from Hillary Clinton’s speeches and those of Netflix’s CEO as part of this anticipatory fiction.

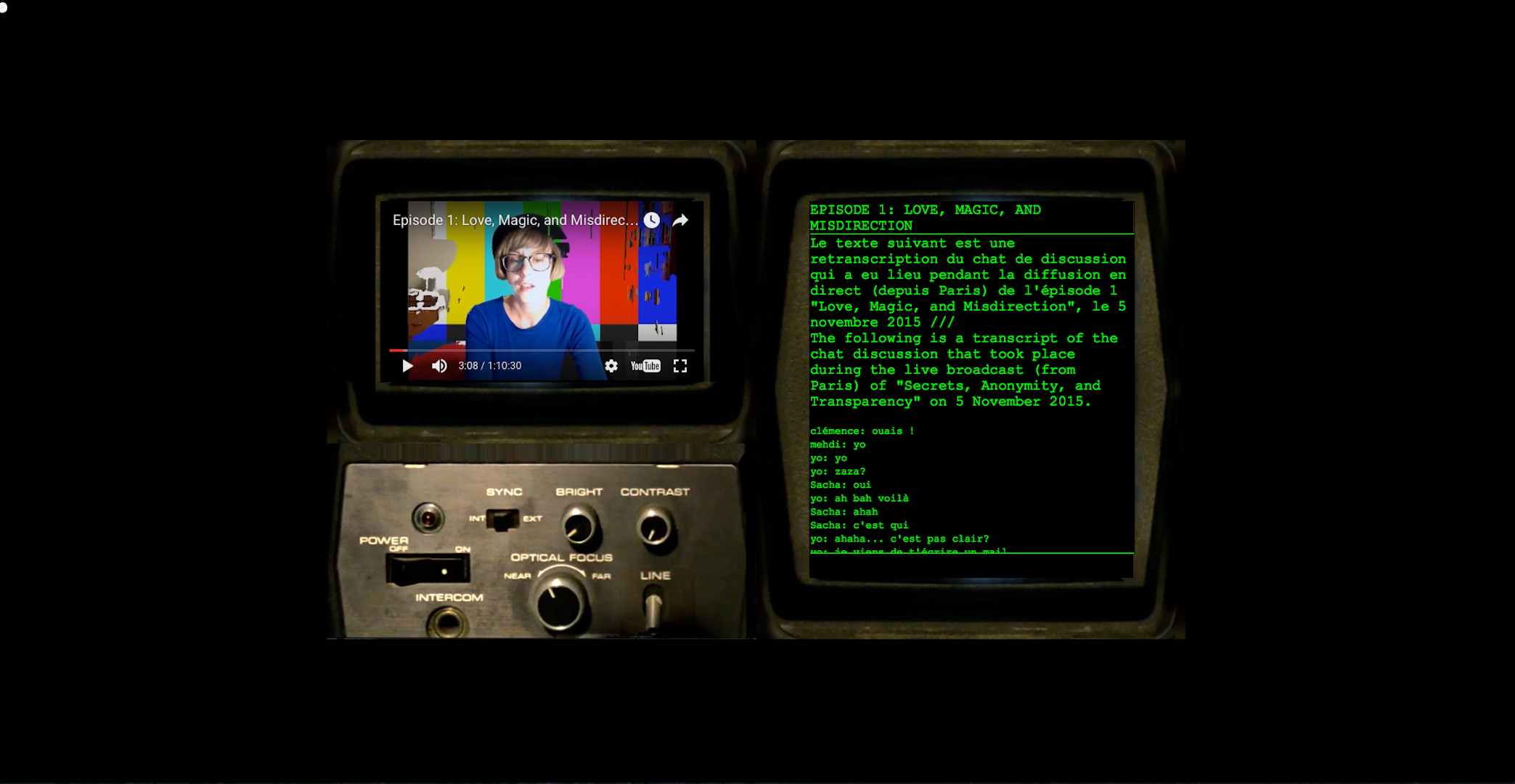

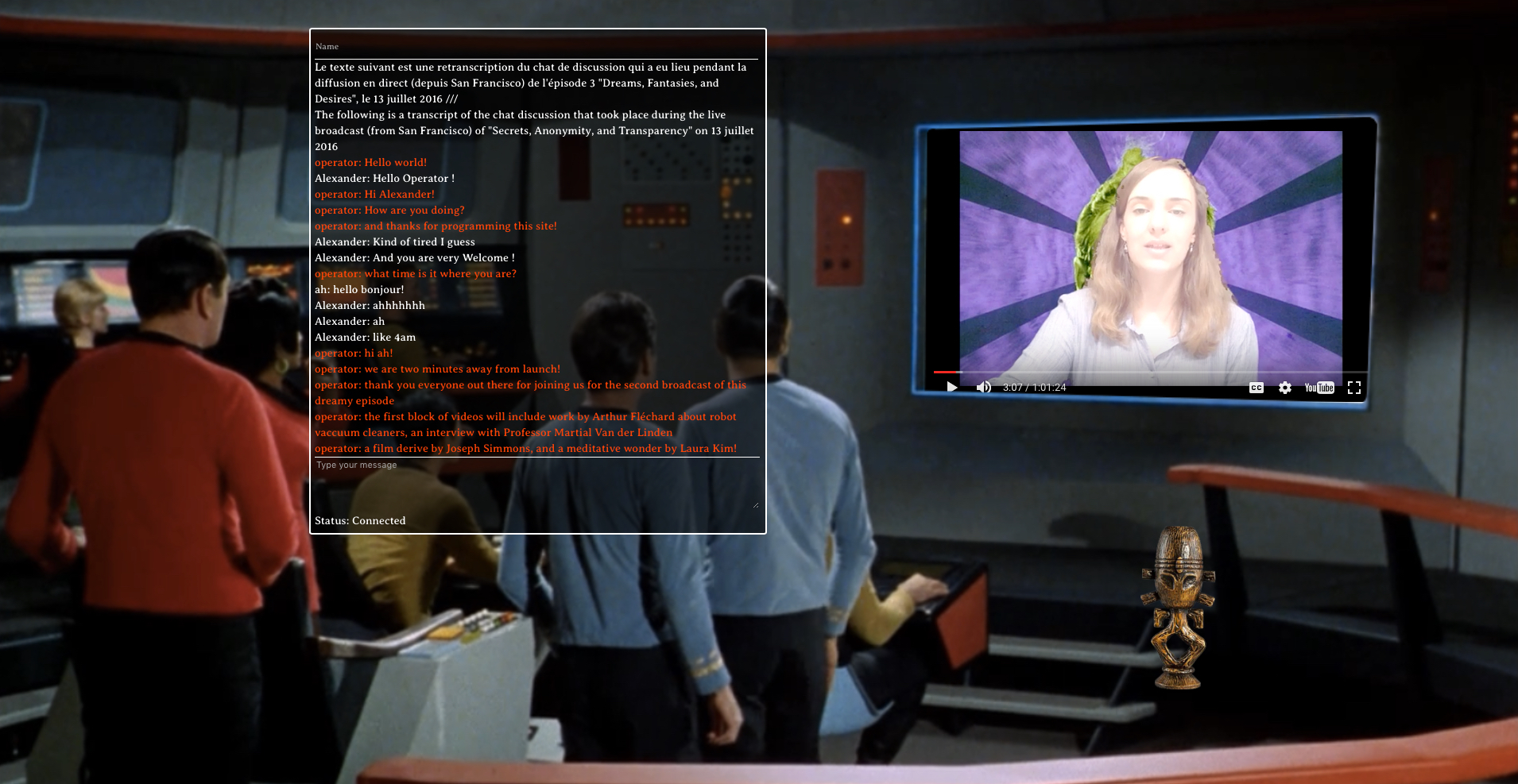

The Big Conversation Space (Niki Korth + Clémence de Montgol er), BCC Channel, in collaboration with Alexander Rhobs. Episode 3 : Rêves, fantasmes et désirs, 2016

Choosing television as a point of reference is thus not just like creating a work situation, but also positioning yourself with a more prescriptive view of what an ideal medium might be. It is in this sense that we can read the research of the BCC Channel, one of whose systems is currently being presented by the CAC Brétigny. The BCC Channel, standing for The Big Culture Conversation Channel, is a project developed by the two artists Niki Korth and Clémence de Montgolfier. Since 2010, they have been working together under the name The Big Conversation Space, “an organization for research, art and consulting, dedicated to all forms, sizes, orientations and formats of conversation”. Each one of the episodes that they put online as streaming, in a space accompanied by a chat room, hybridizes documentary and fictional sources, audio-visual archives, and sequences received during paying calls. This is probably one of the ways in which we must read the persistence, and even the comeback, of television: as a dream, or rather the operative utopia, of re-introducing the situation of global address of television within the interactivity of the Internet, a way of avoiding both the passiveness of the TV viewer and the segmentation of Internet users. And over and above this duality, creating an “analogico-digital”9 conglomerate which adjoins to the layering of technologies the respective advantages of multiple and self-generated situations of declarations.

1 Douglas Coupland, Marshall McLuhan: You Know Nothing of My Work!, 2009, Penguin Canada.

2We are here borrowing the distinction made by Rosalind Krauss between “medium” and “media” in Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, 2000, Thames & Hudson.

3 Friedrich Kittler, Médias optiques. Cours berlinois 1999, 2015, Editions L’Harmattan.

4 Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964: “A cold medium, be it word, manuscript or television, makes more room for the participation of the reader or listener than a hot medium”. And more specifically in relation to television: “Young people who have suffered ten years of television have naturally contracted an imperious habit of in-depth participation, which makes the distant and imaginary objectives of the current culture seem unreal, meaningless and anaemic”.

5 Text from the exhibition: “The importance of presenting this material in a museum of contemporary art is that they were, or are, outside of their time. The common trait of the work is that they cannot be deducted from their era: on the contrary, these ways of recreating the world were at their outset imagined to be different from their era”.

6 Marc Augé, Non-lieux, introduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité, 1992, Editions Seuil.

7 Where he talked with Maeve Connolly, Adeena Mey, Deborah Birch and Joachim Hamou.

8 Henry Jenkins is one of those who have most acutely thought about the collective in the age of transmedia, especially in Convergence Culture, Where Old and New Media Collide, NYU Press, 2006.

9 Jacques Derrida was already using this term in the transcript of his filmed interviews with Bernard Stiegler, in Echographies de la télévision, 1996, p. 174.

“Labor Zero Labor” from 27 August to 27 November at La Friche la Belle de Mai in Marseille http://l-0-l.tv/

“JUMP” from 19 November to 22 January at the CAC Brétigny

(image on top: The Big Conversation Space (Niki Korth + Clémence de Montgolfier), BCC Channel, in collaboration with Alexander Rhobs. Episode 1 : Amour, magie et diversion, 2015.)

- From the issue: 80

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Craft is Back, Drifting all dressed up: portrait of the artist as a nomad, Art & Cultural Appropriation,

Related articles

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret