Don’t Take It Too Seriously

In the text presenting the exhibition ‘Dont take it too seriously’, of which he is the curator, Alexandre Burenkov wonders if post-irony has become the torchbearer of an intellectual and artistic sphere which, stunned, like the whole world, by an incredible reversal of the geopolitical paradigm, is discovering that it is increasingly difficult to find its way in this daily bombardment of fake and other absurd news, the Trumpian sequence that we are experiencing at the beginning of 2025 having reduced the antecedents of the Cambridge Analytica style to the rank of a triffle. But the 47th president of the United States has taken the grotesque to an entirely new level: a former MMA champion speaking at the White House lectern, a ‘ketamine clown’ in the famous Oval Office, a president at war being hustled in front of the world’s media1… Is any of this really serious? The question that Alexandre Burenkov asks us is the following: what attitude should we adopt in the face of what defies an understanding that, until recently, was based to some extent on the non-distortion of facts?

Irony is a sport for educated gentlemen who cultivate a spirit of finesse while not directly getting involved in political and/or linguistic combat, leaving it to others – the activists – to grapple with the task of disentangling truth from falsehood. Post-irony is the disenchanted and depoliticised response of a society with less and less access to the levers of official information now editorialised by algorithms, whose aim is not to inform, that is to say to provide the factual elements necessary for the formation of a personal vision untainted by ideology, but rather to ‘maximise user engagement, to capture our attention and collect our data, to resell it to advertisers for the purposes of targeted advertising or to parties for political propaganda’2.

Post-irony would be an antidote to a massive disorientation campaign orchestrated by ‘algocrats’ who are still inspired by the same venal impulses. Some consider that the only possible response to the consumerist bias of technology would lie in the production and appreciation of works of art, which alone are capable of resisting the monetisable future of all human activity and enterprise: For Ana Longo, there are ‘representations in which this system [industrial post-capitalism] appears to be guided by inhuman ends, a dynamic motivated by its own infinite perpetuation and capable of transforming any form of philosophical or artistic resistance into a productive resource. Technical development would thus become an end in itself, the true engine of economic growth against which the progress of societies is measured3’.

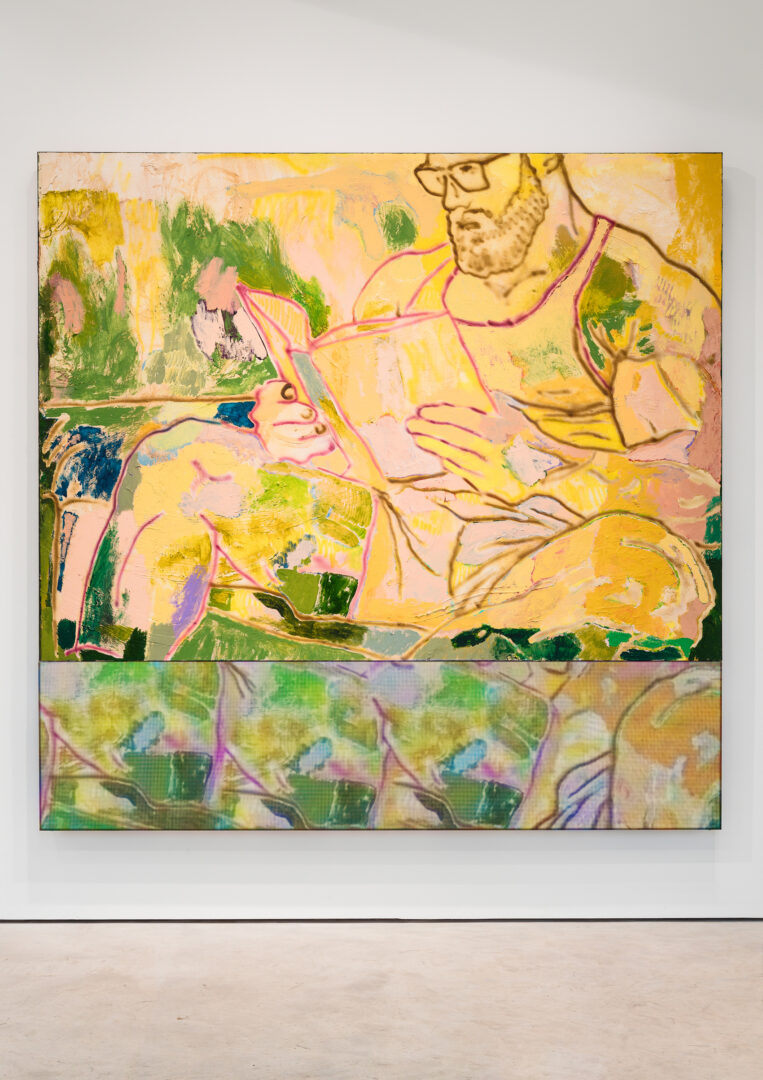

Acrylique, huile et encre sur toile, panneaux LED, lecteur multimédia, vidéo, matériel

/ Acrylic, oil and ink on canvas, LED panels, media player, video, hardware, 200 × 200 cm.

But what can works of art do against this technological vertigo? For the philosopher, any work of art is capable of effectively and resolutely countering the utilitarian and mercantilist thinking that governs the post-capitalism in which we are immersed; for the curator, this thinking does not necessarily inhabit the artists, it is a default result of their practice, more or less conscious. It is not easy to recognise the thesis put forward by Alexander Burenkov in the works presented at the Temnikova & Kasela gallery. How, indeed, can one discern post-irony in a work of art? A partial answer can be found in Anna Solal’s assemblages. Her works refer to the thinking of the philosopher Jacques Ellul, according to whom all merchandise is subject to obsolescence, while a work of art escapes death. The acceleration of the decline of objects is to the artist’s delight, who combines high-tech condensates, such as smartphones and other abandoned objects, to give them back organic, animal forms, thus initiating a process of poetic deconstruction of the fetishism inherent in merchandise. The irony becomes quite clear for objects once considered vital, now simple patterns of an assemblage that disarms their power of seduction.

The exercise is more delicate considering the work of Philipp Timischl, whose mixed paintings and videos question this unprecedented coupling: does the video serve to better appreciate the painting, is it a commentary on the latter, or does it in fact illustrate this dimension of post-irony that is being discussed as the necessary complement to the apprehension of a painting, the latter now being considered insufficient to capture the attention of the spectator? And we know how important this question of attention has become in our society. The two parts of the work comment on and contradict each other like two paradoxical elements, in a shaky mimicry that alters the subject of the work and the subjectivity of its author.

The work of the Lithuanian Robertas Narkus is directly centred on the critique of neoliberal systems, whose contradictions he hyperbolises, between social sculpture and a rehash of relational aesthetics. The piece he is presenting at the gallery is doubly hybrid, the first ‘part’ being composed of an easel/sculpture that recycles the tools of the worker and on which one of his anthropomorphic paintings rests, which represents ‘a new and as yet unnamed form of life’, according to the curator; facing it, another work of the same ilk engages in a strange dialogue with the first ‘character’, like an eminently deceptive and ironic projection of a future cyborgesque society of junk.

The work of the German artist Agnes Scherer, Bonbonnière, brings together two completely different registers: that of the 17th-century elegant lady and that of the tumbler doll. This improbable construction seems to emerge from the unfathomable depths of the artist’s psyche; it could illustrate the essays of Bruno Bettelheim, the author of The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, somewhere between eeriness and the lightness of a child’s toy… But perhaps this combination of impossibilities also refers to an oxymoronic era in which the search for truth is immediately contradicted by its opposite, an era in which a flat earther can easily rub shoulders with the self-proclaimed conqueror of the planet Mars.

The ‘identity’ flags of the American Joshua Citarella referring to the fictitious communities resulting from e-deology, as well as the hybridised textile productions of CAPTCHA and old wallpapers of the Estonian Johanna Ulfshack complete this attempt at an inventory of post-ironic painting and sculpture.

1. These are the various anecdotes related to the start of Donald Trump’s second presidency: McGregor, former MMA champion, talking to the President of the United States who receives him in the Oval Office; ‘ketamine clown’, as MP Claude Malhuret described Elon Musk in a speech to the National Assembly; the famous interview in which Trump told President Zelinsky that it was the latter who had launched the offensive against Russia.

2. Anne Alombert, ‘Alternatives aux réseaux antisociaux’, AOC, no. 1, p. 93.

3. Anna Logo, Le jeu de l’induction, Paris, Éditions Mimésis, p. 195.

Head image : Robertas Narkus, yXG)2A, 2025. Impression jet d’encre, cadre en acier / Inkjet print, steel frame, 165 × 110 cm.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Hilma af Klint, Playground, Lyon Biennial, Anozero' 24, Coimbra Biennal, Signs and Objects. Pop art from the Guggenheim Collection at Guggenheim Museum,

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Thomias Radin

by Caroline Ferreira