Candice Breitz

Candice Breitz, ‘Off Voices’

Curated by Dorothée Duvivier

BPS22, Charleroi, Belgium, until 11 May 2025

In Charleroi, the BPS22 has had the good idea of devoting a solo exhibition to the South African artist Candice Breitz. Bringing together a body of work created between 1994 and 2020, it invites visitors to explore the work of an activist artist whose social activism, private life and artistic creation are inextricably intertwined. The title ‘Off voices’ is a reminder of the many voices that have been silenced, literally extinguished. Candice Breitz’s work as a whole appears as an attempt to amplify these silenced voices. Upstairs, the Ghost series, an early work produced in 1994, seems to be the ideal starting point for the exhibition. The work was created shortly after the artist’s arrival in the United States, where she would continue her studies, and just after the historic elections of April 1994 that ended apartheid in South Africa. Ghost1 has its origins in a set of ten tourist postcards intended for whites, showing African women in traditional dress. Candice Breitz would cover their bodies in Tipp-Ex, leaving their noses, mouths and eyes visible. Reproducing the violence and erasure of black South Africa under the apartheid regime, the work would be very poorly understood and would provoke violent criticism. Some saw it as an expression of racist prejudice. The artist, who was only 22 at the time, will also be defended by those who are aware of his commitment to analysing and questioning white privilege. The texts opposite give an idea of the critical thinking and debate generated by the work since 1994.

Projected on a screen in the main hall, the video work Profile is the artist’s response to her nomination to represent South Africa at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Rather than appearing in front of the camera, Candice Breitz invites ten leading South African artists to feature in the work, which is made up of three short films called self-portraits. Everything merges and mixes here, when questions of class, gender, religion and race arise, when truth and fiction blur to better affirm the elusive and fluctuating nature of identity. Challenging the somewhat facile metaphor of the ‘rainbow nation’ that defines post-apartheid South Africa, the eleven artists ask: who speaks for whom?

Two hundred white shelves act as display units for video cassettes enclosed in black cases that are distinguished only by a white written word. The installation Digest (2020) is reminiscent of the aesthetics of old-fashioned video clubs. It is inspired by the legend of Scheherazade, the most famous of storytellers, who, condemned by her husband to die the next day, told him a story every night, taking care not to reveal the ending. Convinced by her talents as a storyteller, he decides, after a thousand and one nights, to let her live. Created during lockdown, Digest comprises a thousand and one videotapes, each one a hidden story, sealed forever in their polymer sleeve, like a funerary stele of cinema on magnetic tape. Each sleeve is unique, covered in abstract black paint. The word, hand-painted in white, is taken from the title of a film, like To Trek for ‘Star Trek’ (1979). With hundreds of metres of videotape covering a century of cinema, Digest is at once an archive, an inventory and a time capsule of a way of consuming obsolete films. In Charleroi, Candice Breitz has chosen to highlight, alone on a plinth, the word ‘Labour’ to better lead the visitor to the eponymous installation that examines how patriarchal violence can be creatively combated.

Labour (2017-2020) is a series of video installations, each of which consists of footage of a real birth, but in reverse: the newborn is torn from its mother’s arms and reintroduced into her uterus. The whole is presented in booths with austere grey curtains, referring to the peep-show aesthetic of the first presentation devices of Courbet’s L’Origine du monde(1866) [E. F.2]. Each space bears the name of a contemporary dictator written backwards. The installation is accompanied by a matrix decree that is said to have been written by the Secular Council of the Utopian Matriarcat (SCUM2), a feminist authority that applies a policy of zero tolerance towards ‘testosterone eruptions [and] binary extremism’. Speculative fiction in which the world is freed from the chains of patriarchy, the work is ‘a desperate gesture in response to desperate times,’ says the artist.

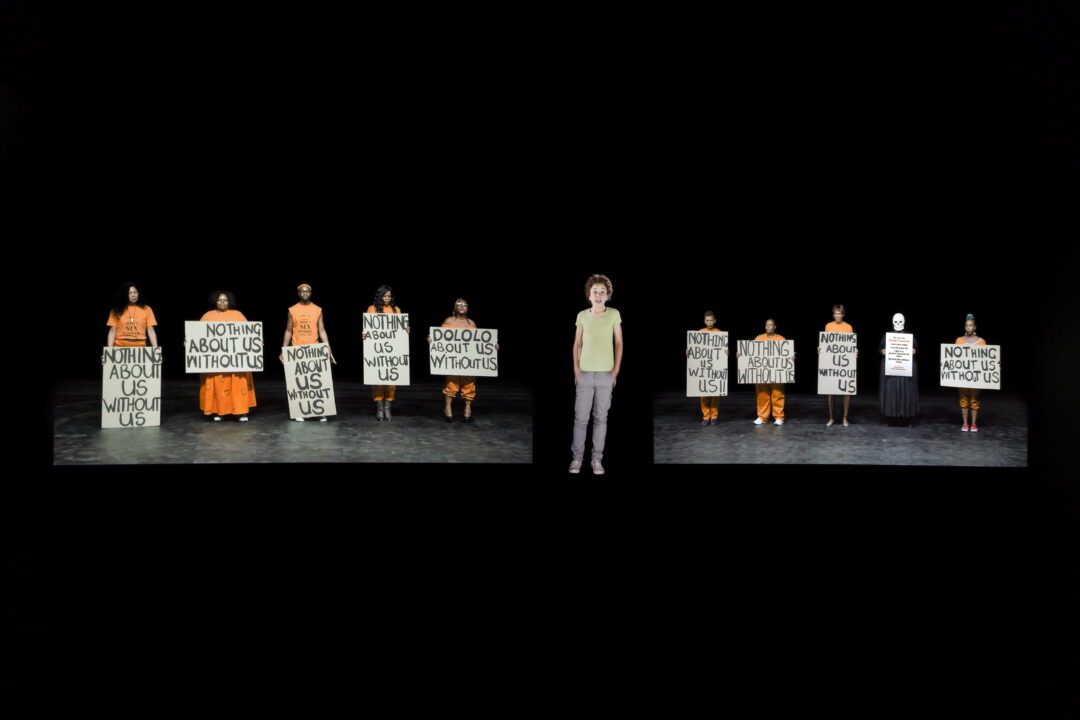

The second space is occupied by TLDR (Too long to read), a spectacular three-channel video installation in which a 12-year-old narrator tells the true story of an ideological battle between two types of feminists, as well as between Amnesty International and a coalition of Hollywood actresses and sex work abolitionists. Between the musical and the ancient choir, eleven sex workers, members of SWEAT3, react to the story being told through slogans they use to claim their rights, all punctuated by protest songs from the South African repertoire. The campaign aims to decriminalise sex work worldwide in order to protect sex workers by providing a legal framework for their profession. But fierce opposition from conservative activists succeeded in attracting the support of a group of Hollywood actresses, from Meryl Streep to Charlize Theron, who defeated the project. TLDR suggests that these actresses signed the petition that went viral without even taking the time to read Amnesty International’s well-documented proposal. TDLR is a critique of the power of the stars and its disastrous consequences, a network of influential but ignorant women who, thanks to their ‘white saviour’ complex, dominate a debate that does not concern them. The work is a reflection on the relationship between whiteness, privilege and visibility, but also on the shortening of attention span. Going back upstairs, the long corridor overlooking the great hall, offering another perspective on TLDR, presents a series of intimate documentary interviews with SWEAT members and invites us to take the time to listen. Through her works, which contain stories that are a blend of reality and fiction, both personal and political, Candice Breitz forces us to face up to our heritage. While we cannot refuse it, we do, however, have an obligation to inform ourselves, to listen, to ask questions. What kind of heirs do we want to be?

Candice Breitz, TLDR, 2017. Installation video 13 canaux. Commande B3 Biennial of the Moving Image, Frankfurt. Courtesy Goodman Gallery (London) et KOW (Berlin).

1The postcards presented in the Belgian exhibition are almost facsimiles – they have been enlarged – of the originals kept at the Tate Modern in London.

2 A nod to Valerie Solanas’ SCUM Manifesto.

3 Sex Workers Education & Advocacy Taskforce, an association based in Cape Town, South Africa.

Head image : Candice Breitz, TLDR (extrait), 2017. Commande B3 Biennial of the Moving Image, Frankfurt. Courtesy Goodman Gallery (London) et KOW (Berlin).

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Camille Llobet, After the End. Maps for Another Future, Wolfgang Tillmans, Bergen Assembly, Aline Bouvy,

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Thomias Radin

by Caroline Ferreira