Jenny Holzer

Thing Indescribable, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, 22.03-9.09.2019

Jenny Holzer is closely bound up with the history of the Bilbao Guggenheim, because the museum has held a monumental work of hers since it opened in 1997: a set of nine columns, more than 12 metres in height, which has pride of place in the museum’s atrium. Back in the Basque country’s capital twenty years later, the artist has been invited to occupy the various rooms and the outside areas. Rubbing shoulders with such an icon as the Guggenheim represents per se a veritable challenge, which only an artist of Holzer’s stature, accustomed to such endeavours, is capable of meeting. Because the Guggenheim is much more than an instantly recognizable building: it is the symbol of a city which has wagered on contemporary art to inject new life into a region that was suffering from the full brunt of de-industrialization. If the American artist’s proposal does manage to rival the spectacular quality of Gehry’s architecture, it does so by adopting the same weapons and the same excess, at the risk, at times, of calling into question the coherence of a work made above all to counter the violence of the ruling class.

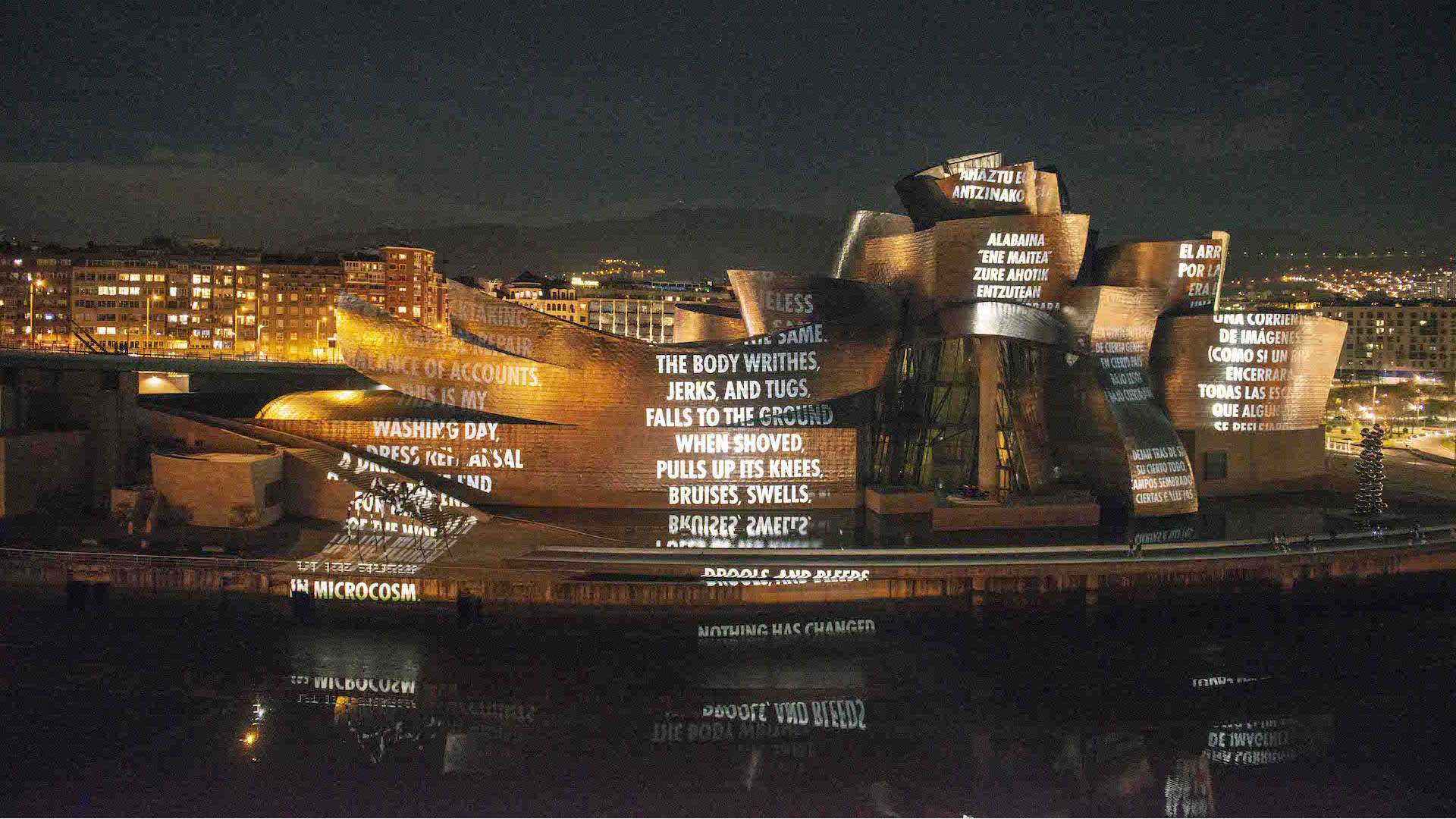

The exhibition, titled “Thing Indescribable”, echoes twice over the architectural wager represented by the museum, both by being lodged in its bowels and by developing across the façade that gives onto the river, with a series of monumental projections which slide and undulate on the building’s reptilian surface. It has to be said that from the viewpoint of visual effectiveness, the arrangement is on a par with the work of an artist who has always managed to make use of the urban setting of places where her ideas have been developed: proof of this are her countless works in the heart of metropolises, the most famous of which is perhaps her Times Square installation, where she managed to have her famous slogans scrolling by in the very hub of one of the planet’s busiest places. Jenny Holzer’s art spontaneously calls for a (re)conquest of the public place: by using the very channels of those she questions with regard to their responsibility for the dysfunctional nature of our world, Holzer puts herself on the same level of visual and media effectiveness as these latter. The merit of the infiltration of these hyper-places1 is that it installs the artist’s disruptive messages within highly exposed and highly connected spaces, with disproportionate concentrations of people in small areas. For this artist, who arrived after the generation of early conceptual artists, it is no longer enough to highlight the importance of language: for Holzer, if art must remain resolutely linguistic, this language must be displayed here, there and everywhere, and must no longer turn its back on the possibility of an extreme visibility, by appropriating all the media and surfaces which may provide it with the highest level of reception. Holzer’s past, with its share of family problems, has also marked her and, in a way, persuaded her that the disembodied formalism of conceptual art has no longer sufficed for describing society’s contradictions and violence: art must clearly express an opposition to the values of consumer society, something which she applies to the heart of New York City by choosing to cause interferences with ‘business as usual’, but at the risk of drowning her message beneath an inflation of every manner of data: the ups and downs of the Dow Jones Index, sports results, infotainment, and so on, which all hallmark the undifferentiated flow of worldwide information. The other problem raised by such “installations” is their ornamental character: in Bilbao, the gigantic scale of the projections competes with Gehry’s architecture, and even cancels it, because the building has to be plunged into half-light in order to make the procession of lit words visible.

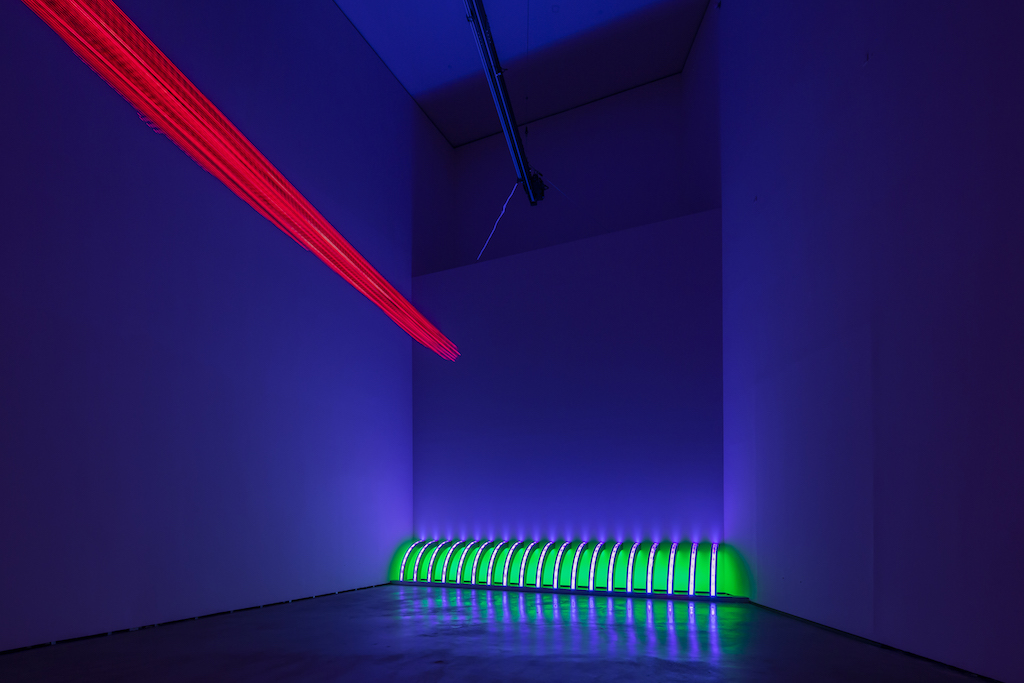

Inside the museum, this contradiction is magnified by the artist’s fascination with high tech tools which seem out of synch with the soberness of the slogan, with the dernier cri scrolling screens making even a reading of the messages difficult, which just about takes the biscuit when you are trying to work on the effectiveness and clarity of the statements. Luckily, some rooms temper this technological drift. Room no. 5 brings together Holzer’s famous Truisms, a mixture of aphorisms and real phony maxims that have gradually invaded T-shirts, caps, public benches, electric panels, and the like, as well as the Inflammatory Essays which represent the core of the artist’s rebellious thinking, and took the same path of proliferation as the Truisms. The walls, completely covered with coloured diagonals, form an ensemble that is as simple as it is effective in its display, tracing a four-coloured box for these sarcophagi in which there are messages from anonymous speakers describing the absurdity of the dead during the Aids epidemic (Laments, 1989); another more recent sarcophagus bears in marble the words of the poetess Anna Swirszincka railing against the brutality of war: this sober quality of the stelae, combined with a straightforward symbolism lends the whole thing a remarkable solemnity which contrasts sharply with the flashy tendency of the other installations. Sometimes the desire to create shocks of awareness takes on extreme forms as in Ram, 2016, where the pile of human bones designed to highlight the absurdity of the war in Afghanistan is disquieting: this installation gives rise to the same questions as before about the awareness strategies used by the artist. Thinking again about room 6 and the artist’s makeshift beginnings, we might almost lament the craft, punk flavour of her early experiments.

1 Michel Lussault, Hyper-lieux. Les nouvelles géographies politiques de la mondialisation, Paris, Seuil, 2018.

Image on top: Jenny Holzer, For Bilbao, 2019. Text : Anna Świrszczyńska, “Lives One More Hour” from Building the Barricade, English translation by Piotr Florczyk, used with permission of Ludmiła Adamska-Orłowska and the translator © 2016 Tavern Books ; Bernardo Atxaga, “Trikuarena” from Six Basque Poets, 2007. © 1990 Bernardo Atxaga, used with permission of Bernardo Atxaga, © 2019 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo : Erika Ede.

- From the issue: 90

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Don't Take It Too Seriously, Hilma af Klint, Playground, Lyon Biennial, Anozero' 24, Coimbra Biennal,

Related articles

Streaming from our eyes

by Gabriela Anco

Don’t Take It Too Seriously

by Patrice Joly

Déborah Bron & Camille Sevez

by Gabriela Anco