Teresa Margolles

“You fall in line or they put you in line”, BPS22, Charleroi, 28.09.2019 – 05.01.2020

The voices of ghosts rustle in the world’s antechamber. This is the persistent feeling one has when looking at the works of Teresa Margolles, with whom forms of violence are expressed between the lines. Born in Culiacán in 1963, where the network of narco-traffickers rules the roost, the artist has turned her work into a denunciation of common-or-garden violence in Mexico—disappearances and deaths, murders, and threats issued by the drug cartels— echoing the title of her show at the BPS22: “You fall in line or they put you in line”. She has seen her fill of dead bodies. With a degree in communications, and as a medical examiner in a morgue in Mexico City in the 1990s, she takes her material from bodies she is responsible for. The performances produced within the SEMEFO1 collective directly exercise those watching macabre presentations: organs removed from deceased persons, photographs of rotting corpses, and mummified animals… Since the start of the “war on the drug cartels” declared in 2006 by then president Felipe Calderón, there have been 275,000 victims.2 Organized crime attacks both rival gangs and people on the sidelines: migrants, the homeless, drug addicts, and people too poor to be given a burial, or to be identified, for fear of reprisals. Stray bullets are common currency. This is one of the reasons why Margolles decided to set up home in Madrid, abandoned by the Mexican government after representing her country at the Venice Biennial, ten years ago now (Sangre recuperada, 2009). Instead of the flood of images making death something banal, the artist chooses to show the traces of victims. Water that has been used to wash the dead, impacts of bullets and bodily fluids all end up playing the role of silent witnesses. The minimal language used condenses things even more: matter, the historical content, and the emotional impact. The boundary of this posture involves an almost indiscernible criticism which conditions the meaning of the works to their exegesis.

Invited for the first time to Belgium by the BPS22, the Provincial Art Museum in Hainaut, Margolles has made three visits to walk around the city since last February. Tracking alternative economies and apparent signs of poverty, she has reacted to the social inequalities of this region, Belgium’s poorest, by re-galvanizing the procedures that are dear to her. This is what makes this exhibition so valuable, half made up of in situ works. In the wing that has been turned into a ‘white cube’, spatially disconnected from the Charleroi works, a selection of works produced since 2016 describes the precarious situation of women of South America: kidnappings, rapes, and femicides are on the increase in Ciudad Juarez, on the US/Mexican border, but also in Bolivia, and Venezuela. Pička (2018) is a ritual of exorcism: in this video, a young woman compulsively repeats, like an animal caught in a trap, the insult that violently assigns her to her sex: “Pička” = “pussy”. She belongs to a group of women whom it is authorized to rape. Previously, she had given the artist the pullover she was wearing during the last assault on her, like a proof whose words seek to unravel the sense, and abstract the meaning. Along the passageway, the alignment of reproductions of posters of disappeared students and working women seems to extend beyond the wall. Lacerated and peeled, on the verge of disappearance, they take us as witnesses (Pesquisas [Enquiries/Search notices], 2016-2019). This year, the Venice Biennale also showed some of these photocopies, posted on large shop windows, vibrating with the sounds of trains, freight trains which migrants illegally cling to, to reach the border (La Busqueda (2) [The Search], 2014).

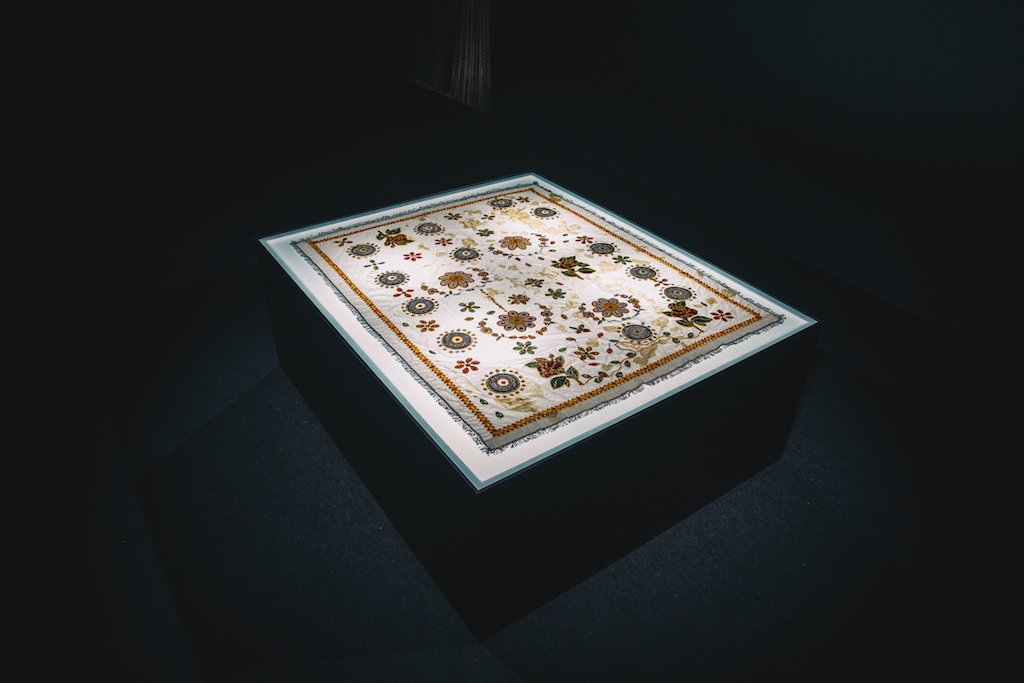

Here we perceive the contained violence of this dull rumbling. The great industrial halls of 1911, in their basilica-like architecture, resound in particular with these works, which draw their strength from religious iconography. The stones loaded by people smuggling goods from Venezuela to Colombia are so many crosses being borne (Trocheras con piedras [stone bearers]). A shroud and relics imagery runs between the lines in these forms which touch the sacred. This is especially the case with the cloth soaked in the blood of a murdered woman in Bolivia, embroidered with traditional motifs by craftswomen as a mark of reparation and re-appropriation (Wila Patjharu/Sobre la sangre [On blood], 2016). Empathy might turn into disgust were it not based on the divine aura of the relics of saints, heightened by the light box on which the object rests, ambiguously fascinating. These material remains turn victims into martyrs and embroidery into a resurrection by the community.

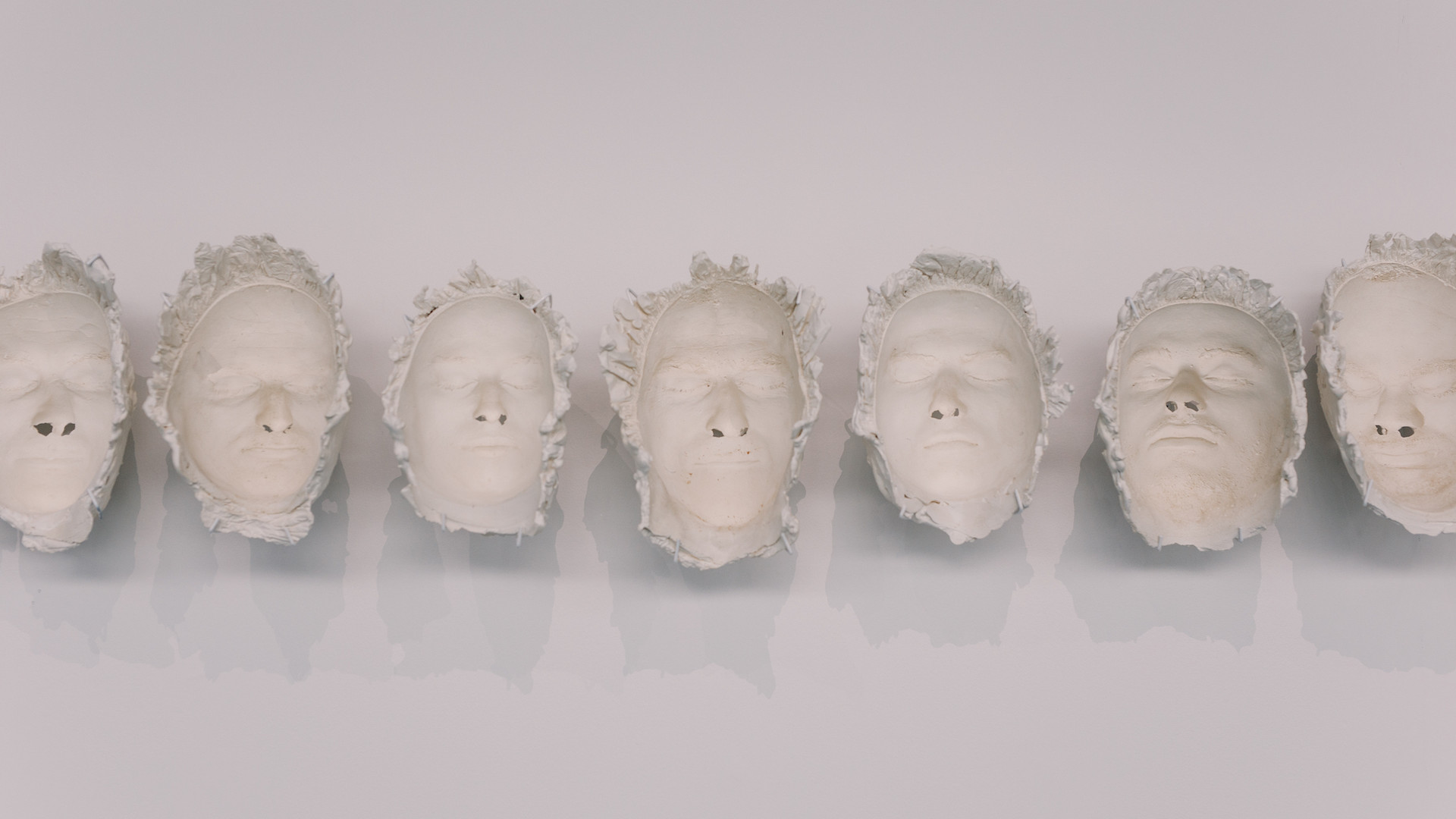

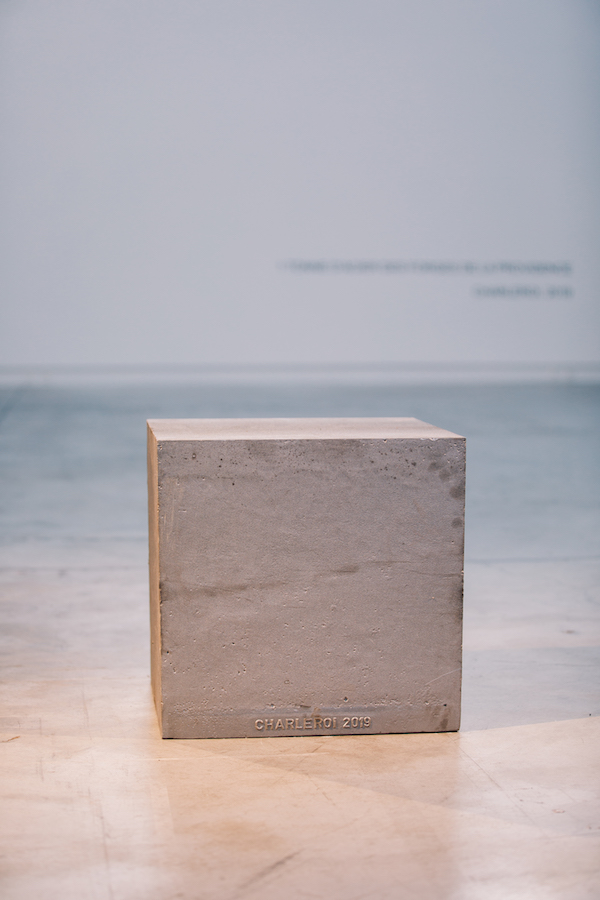

In the large room, where the iron structure is still visible, the new works tend to offset the monumentality. Lined up on the wall, the 38 plaster casts of drug addicts, the “walking dead”, drug dealers and prostitutes, sometimes stained with blood, summon the tradition not only of the death mask, but also of the shroud of Christ (Improntas de la calle [Imprints of the street], 2019). This paradoxical homage suggests the invisibility of the albeit thoroughly alive people left out of the former mining and steel-making area, calling to mind the procedure used in 1997 for Catafalco [Catafalque], using the body of a murdered person. While the whiteness of the material conjures up the ghostly and unique apparition of each acheiropoietic (i.e. made without human hand) image, the hanging, on the other hand, underscores the mass production and suggests a generalized situation. Te alineas o te alineamos [You fall in line or they put you in line] is a threat issued by narco-traffickers in Mexico. The engraved letters shine out ten metres up on the cement wall. The order is violently applied to these marginal people, with the line also conjuring up that of a firing range. In the middle of the space, a steel cube, weighing one ton, recalls American Minimalism (Tonne. Forges de la Providence (Charleroi), 2019). Here the artist re-uses old forms, like the volume of concrete enclosing the body of a newborn in Entierro/Burial (1999). At the time, a mother had in fact begged the artist not to send the corpse of her baby, whose burial she could not afford, in the communal grave. So Margolles made her a moveable funeral chamber, looking like some primary structure, with a hollow for the body in the middle. At Charleroi, the sculpture is solid. The mass of metal has something monumental about it. Composed of vestiges from the Charleroi steelworks, now closed for good for seven years, the object thus expresses a grandeur that has become derisory in this monumental hall. At best, a pedestal for despair. Visitors can sense the density of the piece, they are even invited to push the mass, in vain, with their fingerprints in the porous matter making trails which, for us, take on the hue of blood. The industrial grave is not a box. It is not a block of darkness putting up resistance. The object’s identity is, moreover, cast on one side. Yet while Providence no longer booms, and the machinery is at a standstill, there are ghosts moaning in a deafening silence.

- The SEMEFO collective, Servicio Médico Forense or Legal Medical Service, active from 1990 to1999, was founded by Teresa Margolles, Arturo Angulo Gallardo, Juan Luis García Zavaleta and Carlos López Orozco.

- Thierry Noël, La guerre des cartels : 30 ans de trafic de drogue au Mexique, éditions Vendémiaire, 2019.

Image on top: Teresa Margolles, Improntas de la calle (detail), 2019. BPS22. © Photo : Leslie Artamonow

- From the issue: 92

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Pauline Boudry & Renate Lorenz, Josephine Meckseper,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset