Lucas Arruda

Lucas Arruda’s small paintings are surprising in that they take the opposite tack to exaggeration and express simplicity as if it were obvious. They are the complete opposite of the flashiness and clickbait of images made for screens, which are ready to resort to any exaggeration to stand out. Yet his paintings are appealing: they awaken an aesthetic pleasure that is not so common today, and perhaps this pleasure is untimely, as suggested by the author of the introduction to the Nîmes catalogue[1]. Or is it sliding towards the outdated? Arruda’s paintings certainly plunge us into a contemplative state, similar to that experienced when looking at Caspar David Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea (1810). But their format is much smaller, generally around thirty centimetres, and there is no monk. They are deserted landscapes, hence the title given to the collection, “Deserto-Modelo”, an expression taken from a writing by the Brazilian poet João Cabral de Melo Neto (1920-1999).

The artist seems happy to embrace the reference to the 19th century. During his art studies in São Paulo, where he was born in 1983 and where he lives and works, he took a trip to Italy, much like the American artists depicted through the character of Roderick Hudson in Henry James’ 1875 novel, or like J. M. W. Turner’s Italian Tours in the 1820s, a painter who inevitably comes to mind here. One cannot help but wonder whether Arruda saw the Italian landscapes that Camille Corot painted in 1827. Turner in the 1820s, a painter who inevitably comes to mind here. One cannot help but think that Arruda saw the Italian landscapes that Camille Corot saw and the resulting paintings by the Barbizon master. His relationship with the 19th century was the subject of an exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, where his paintings were juxtaposed with those of Courbet, Théodore Rousseau and, above all, Monet, because he also works in series, seeking to paint light rather than objects.

Huile sur toile / Oil on canvas, 20 × 20 cm. © DR

As part of the France-Brazil season, two major exhibitions of the artist’s work (the first monographic exhibitions of his work in France outside of a gallery) were organised: ‘Qu’importe le paysage’ at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and ‘Deserto-Modelo’ at the Carré d’Art in Nîmes. In both exhibitions, his small paintings are soberly aligned, making us understand that they must be understood in their own temporality. But what is that temporality? This is where the two exhibitions diverge. Hanging the paintings near Monet’s works is very judicious in terms of form and art history, and also excellent for raising their value on the art market, but it obscures the fact that they were painted in a completely different context. In particular, they are contemporary with the baroque productions of AI. In short, they are caught up in a relationship with the image that is very different from that of the 19th century… The Carré d’Art exhibition, which shows the paintings, but also a ready-made object, a slide show, an installation and a video, invites us to put this into perspective, including questioning what it means today to devote time to contemplation.

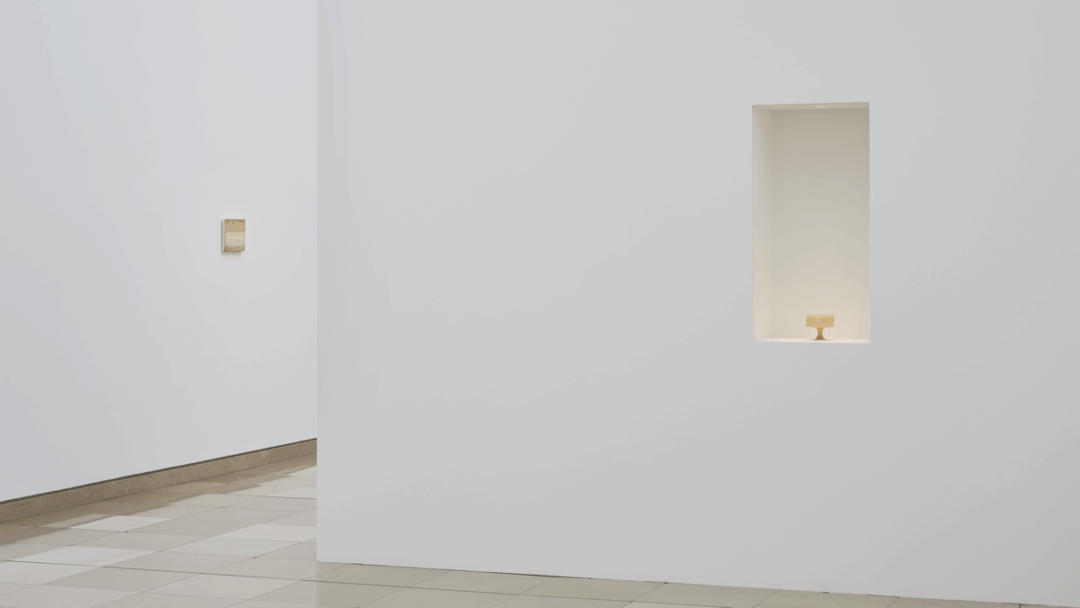

In Norman Foster’s sleek architecture, hung very sparingly, with sometimes only one painting per picture rail, the whole acquires a minimalist dimension, and in many ways, one might think one was discovering the spiritual heir of Robert Ryman. The paintings are not all white, far from it, but there are still a number of them, and those that are coloured are done so in pastel or faded colours. It should also be said that, inspired by seashores, gardens and forests, these paintings convey the humidity, mists and atmospheric heat of the tropical landscapes that the artist encounters. Another point to note is that he does not paint from life, but in his studio, from memory; details fade away in favour of memories of sensations and reconstructions by the imagination. Take, for example, the seascapes he has been painting since the early 2010s: with similar compositions, a slightly agitated sky in shades of beige or grey, or dark in the case of nocturnes, occupying most of the time more than three-quarters of the pictorial surface, a sea reduced to a thin horizontal strip without waves, echoed below by another thin strip for the shore, the canvases are on the borderline between figuration and abstraction. No clouds stand out, no waves animate the water, no living beings walk about; everything has been removed to retain only the bare minimum. From a material point of view, the same is true: in the layer of paint, we can see the gestures that have removed the surplus to retain only the essential. More precisely, the paintings are covered with encaustic and then scraped, on a background previously painted in a carefully chosen colour that reappears through transparency and, above all, appears at the edges of the surface, like a frame. For example, the paintings devoted to the rainforest have a dark background that disturbs their luminosity and reveals this manufacturing secret right at the edge. This way of leaving a barely visible border at the corner of the frame fully inscribes Arruda’s work in contemporary painting.

The impression of a work that is not only contemplative and timeless, but also contributes to a reflection on the different media of images today – according to the distinction emphasised by W. J. T. Mitchell between image and picture[2] – is confirmed by the presence of pieces using media other than painting. Firstly, a small alabaster vase, commissioned by the artist from a craftsman based on an archaeological model, displayed in the middle of the paintings, is a plea for the beauty of the material, its nuances and its ability to capture light. Further on, a slide show presented in a completely darkened space, with only two large armchairs in which to sink comfortably, presents us with the dark side of the small, soothing paintings. Composed of 81 slides painted, hatched, even scribbled with agitation on the plastic material of the film, it strikes us like a storm that has been brewing and has finally broken. Its title, Three Days and Three Nights from the Deserto-Modelo Series (2023), clearly indicates that it is linked to the series, as a supplement, clarification, or focus, in the manner of a spin-off. Then, an installation on the scale of an entire room pushes the exploration of luminous painting to its radical extreme. On the walls are diptychs composed of a rectangle painted in white, very slightly tinted with colour, and another rectangle formed purely and simply by a projection of white light. You have to stay in the room for a while to clearly perceive all their contours – an experience that makes you want to go back and observe the nuances of whites and colours in the small paintings.

The same is true of the last work that closes the exhibition in Nîmes, a video from 2018, the only one in the artist’s body of work to date. Through its atmosphere, framing and subject matter, it provides a new, powerful and embodied interpretation. Composed of excerpts from a 1962 film found on social media, it is entitled Neutral Corner, in reference to the corner where a boxer must stand during a knockout. This is precisely what the American fighter in the filmed match did not do, striking his opponent, the Cuban champion, to death. The artist has retained many of the original images’ abstract framing, especially the surface of the floor crossed by one or two ropes from the ring, echoing the composition of his paintings, which cast a shadow of mourning over the exhibition.

1. Germano Dusha, Deserto-Modelo, Nîmes, Carré d’Art, 2025. To describe this pleasure, he speaks of a ‘state of suspension in which vision oscillates between presence and absence’ when faced with paintings ‘imbued with a mystical aura’.

2. W. J. T. Mitchell, What do Pictures Want?, The Lives and Loves of Images, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005; French translation: Que veulent les images ? Une critique de la culture visuelle, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2014. He distinguishes between the ‘image’ (image), an immaterial figure that needs a medium to reveal itself, and the ‘image’ as it is associated with a defined material medium (picture).

Head image : Vues de l’expostion / Exhibition views of Lucas Arruda, « Deserto-Modelo », Carré d’Art – musée d’art contemporain de Nîmes, 2025. © DR

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Alicja Kwade, Lou Masduraud, Diego Bianchi, Sean Scully, Peter Friedl,

Related articles

Julie Béna

by Anna Kerekes

David Claerbout

by Guillaume Lasserre

Jean-Charles de Quillacq

by Anne Bonnin