Lou Masduraud

During this first quarter of a century, a number of artists have made their mark, unafraid of heavy materials, large-scale projects, and imposing volumes, combining them with finely crafted details. To name a few, Anita Molinero, Stéphanie Cherpin, and Caroline Mesquita on the French scene, Mika Rottenberg and June Crespo on the international scene, and Delphine Reist to establish a Geneva connection, since Lou Masduraud studied and lives in Geneva—each with her own style and way of doing things, but all ready to put on heavy boots and go out to collect scrap metal or don a protective mask at the foundry. No more making themselves small, apologizing for being there, or feeling illegitimate, women artists occupy exhibition spaces with great freedom of spirit, while remaining part of art history movements, particularly assemblage and informal art, and following in the footsteps of great pioneers such as Niki de Saint Phalle, Eva Hesse, and Louise Bourgeois.

Among them, in the current generation of artists in their thirties, Lou Masduraud occupies a very prominent place. She creates fountains, street lamps, and large installations in metal, marble, and ceramics, with the particularity, as she points out, of combining the manipulation of materials with another artistic heritage that may seem distant at first glance, namely institutional critique [1]. To put it bluntly, she reconciles a sensual taste for the plastic qualities of the material—for example, the warm tones and brilliance of copper that evolve into gray-green hues matted by oxidation—with interventions in exhibition spaces to reveal their backstage areas and inner workings. If there is something of Eva Hesse in her work, there is also something of Michael Asher, who, among other things, knocked down the walls of a gallery to show the public the storage rooms and offices. In Lou Masduraud’s work, this reconciliation of the two axes, which has been at the heart of her work for several years, is particularly evident in the exhibition “Ta crème immunitaire” at the Grand Café in Saint-Nazaire. It is worth noting the beautifully written title, which is also the title of one of the works on display: it immediately plunges us into a world of textures and attention.

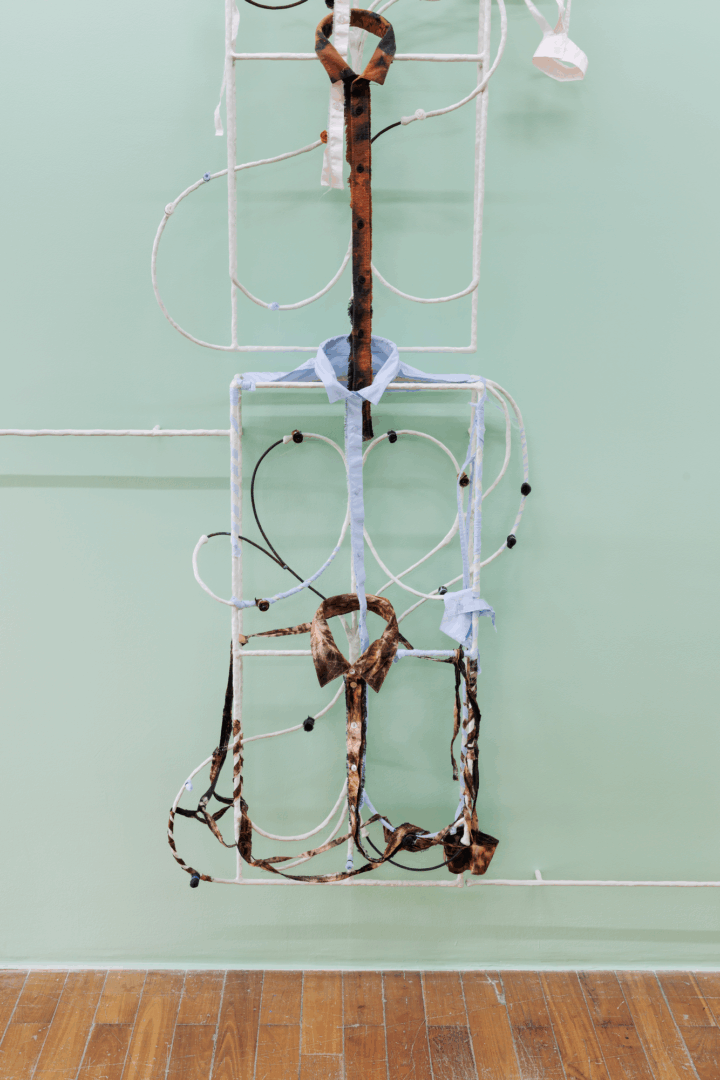

Steel, epoxy paste, paint, feather, textile, coral, shell, mother-of-pearl, quartz, amber, wood, medicine, variable dimensions. Exhibition view of « Ta crème immunitaire » Grand Café – centre d’art contemporain, Saint‐Nazaire, France, 2025. Courtesy of the artist. Photo : © Salim Santa Lucia.

Invited by Sophie Legrandjacques, director and curator of the exhibition, to take over the premises before a future renovation, the young artist has produced and installed works that both dress and undress the space, filling and emptying it. From this point of view, it is interesting to note that, at the same time, Wolfgang Tillmans was invited to undertake a similar project at the Bibliothèque publique d’information, in the deserted Centre Pompidou; his photos cover the architecture of the library to reveal how empty it now is. The same is true of Lou Masduraud’s approach at the Grand Café, which could be described as the opposite of the white cube, or even, as we shall see, the ante-white cube, in the sense that the walls are not seen as a setting that isolates the space from the world, but as interfaces through which art dialogues with its surroundings, in this case the architectural history of the place. The Grand Café, as its name suggests, was a café-restaurant—and in fact, one of the previously invited artists, Francesco Tropa, in 2018, had transformed it into a café with a sign, tables, and bar stools in the middle of the artworks[2]—adapted over the years to its new functions, with the construction of partitions to provide good hanging surfaces, the closure of doors and adjoining spaces to allow for fluid movement—in short, to make this space resemble a white cube : a construction that Lou Masduraud deconstructs both literally and figuratively.

She does this first by continuing a work she has already been doing since 2019 in other venues and exhibitions, entitled Plan d’évasion (Escape Plan), which consists of making air vents, like those seen in the street to ventilate underground spaces while protecting them from break-ins. Installed at the bottom of perforated partitions, they allow the public to glimpse unused areas and become aware that the exhibition space that welcomes them is a space built according to codes, modes, and needs. But these ventilation shafts, rectangular objects composed of grilles, are also paintings with holes. Those on display at the Grand Café are made of glazed ceramic (but others in the series are made of brass, bronze, or wood, depending on the artist’s experiments); fabric ribbons have been added, tied like padlocks on bridges, evoking people who have passed by and wanted to leave a trace. The word “soupirail” (basement window) is synonymous with “soupir” (sigh), a breath of melancholy[3]. In the exhibition, and this time produced by the Grand Café, a few larger-format paintings, 168 x 100 cm, amplify the action of the basement windows: they adorn the walls of the ground floor rooms with orange-colored patterns drawn on darker backgrounds which, as we understand when we get closer, are surfaces pierced with holes. Composed of lace cut from copper sheets, these paintings, with their darker or heterogeneous parts, open up onto the architecture of the building. Through one of them, you can even see the restaurant’s old toilets, which have been condemned. The artist has written a very enlightening text, almost a poem, about these holes:

“I made sculptures in the shape of holes […].

It’s difficult to sculpt a hole, because it’s a lack of material.

Instead of sculpting the material, you have to make the void exist.

And a passage through that void.

So I have to form the contours of the hole: a context to cross, to go beyond, to pierce […].”

“Holes play with boundaries, the spaces behind spaces, and, to elaborate on the poetic meaning, they make us feel like Alice when she passes through the looking glass in her living room[4].”

In the center of the large room on the ground floor, a monumental work from 2024, freely reproducing the space of a urinal, provides a counterpoint. Its title, Self-Portrait as a Fountain of You—for those familiar with 20th-century art history, it echoes other well-known works—refers to Bruce Nauman’s self-portrait, Self-Portrait as a Fountain (1966), which itself refers to a certain other, earlier fountain, a urinal, precisely… But what is crazy and refreshing (for a fountain, that’s good!) in this web of famous references is that they are present, but in a minor way; they may come to mind, but without being decisive or legitimizing. Lou Masduraud’s urinal installation operates on another level, not as a modernist provocation of placing an object of low origin in a place of high culture, but rather as a contemporary reflection on public spaces that are not entirely public, at least not for all audiences, as they are clearly gendered. And here we are no longer so much questioning the gallery space as other spaces that are socially determined to direct the movement of bodies according to historical norms. In other words, the work is more about the way spaces affect bodies, even flesh. Several elements in this installation demonstrate this, notably a sculpture in the shape of unbuttoned trousers, whose legs end as if cut off, in a pipe, while on the walls behind them, lines evoke jets of urine. We have the feeling of rubbing up against something taboo.

Another work demonstrates the artist’s interest in pipes and plumbing, while bringing us back to the bridge she builds between the tradition of craft and institutional critique: the Sculptures volantes. These are ten heavy silver rings, more or less figurative in shape, which resemble construction or plumbing elements, at least one of them, entitled Flying Mixer Tap—this is an opportunity to mention Lou Masduraud’s attachment to the work of Robert Gober, from the point of view of plumbing iconography. They are intended to be worn by people who work at the art center, from the director to the technicians, regardless of position or gender, passing from hand to hand during visits or events. Thus, the work is visible-invisible, scattered throughout the building, but above all, it materializes an idea that is always worth remembering: a place such as the Grand Café, a free public cultural space, exists thanks to a dedicated team convinced that art is something to be experienced on a daily basis—and in the case of the rings, right against the skin.

Finally, one work in the exhibition has a special status, as it was co-created with Christine Masduraud, a psychoanalyst, self-taught artist who works with textiles, and mother of the artist. In the back-and-forth between them, an object, a rope, was transformed into a suspended sculpture and given a title, Quel est l’objet (What is the object) (also finely crafted) de la demande ? The piece blends beautifully into the exhibition as a whole, and ultimately into art history: it recalls Eva Hesse’s works collapsing under the weight of their own material. In recent times, several artists have invited their mothers or grandmothers to their exhibitions, for example Stéphanie Cherpin a few years ago in Château-Gontier[5], or more recently Vivian Suter at the Palais de Tokyo, showing their inspiring and encouraging role at the heart of creation, in a very real artistic lineage. The very touching work Quel est l’objet de la demande ? (What is the subject of the request?) can be interpreted as a tribute to artists who are role models and thanks to whom the work can become what it is, artists we discover in books and in schools, but also artists who are close to us, not necessarily stars, such as a mother.

[1] Discussion with the artist, June 2025.

[2] See www.zerodeux.fr/reviews/francisco-tropa-3/

[3] One of his previous exhibitions was entitled “systm soupir” (sigh system), presented at the Maison populaire de Montreuil in 2021.

[4] Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, 1871

[5] See www.zerodeux.fr/reviews/gontierama-2020/

Head image : Lou Masduraud, exhibition view of « Ta crème immunitaire », Grand Café – centre d’art contemporain, Saint‐Nazaire, France, 2025. Courtesy of the artist. Photo : © Salim Santa Lucia.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Alicja Kwade, Lucas Arruda, Diego Bianchi, Sean Scully, Peter Friedl,

Related articles

Julie Béna

by Anna Kerekes

David Claerbout

by Guillaume Lasserre

Jean-Charles de Quillacq

by Anne Bonnin