Bharti Kher

The artistic career of Bharti Kher, born in London in 1969 and based in New Delhi since the early 1990s, has been marked by displacement and liminality. Her move to India, motivated by her encounter with artist Subodh Gupta, crystallized the paradoxical experience of an intimate strangeness: that of a “return” to a country of origin in which she was not born. This discrepancy fuels a practice that crosses cultural, social, and symbolic boundaries, rejecting any fixed definition of identity. By questioning authenticity and origin as vectors of belonging, Kher explores the possible transformations and metamorphoses of female bodies. These bodies, directly or indirectly present in each of the artist’s works, are figures that reflect the hybrid nature of existence.

Exhibited around the world, her paintings, sculptures, and installations engage in a dialogue that is both inspired by and critical of Western canons (from Duchampian ready-mades to Pistoletto’s mirrors, from Bridget Riley’s Op Art to Robert Ryman’s minimalist monochromes, from pointillism to abstract expressionism, from ancient Greek statuary to images from Ovidian literature), which she diverts and mixes with references to Indian culture, such as Hindu mythologies, tantric traditions, and the textile art of Mrinalini Mukherjee. Through these syncretisms, and with a touch of denunciatory irony, she has created her own visual language based on the ornamental and sartorial emblems worn by Indian women, such as the bindi, the sari, and the bangle.

Bois, bindis, acier doux, sari, résine, quartz vert, fil / Wood, bindis, mild steel, sari, resin, green quartz, thread. 100 × 35 13/16 × 35 13/16 pouces / inches. © Bharti Kher/ ADAGP, Paris 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

The material energies of the bindi

Since 1995, Bharti Kher has made the bindi her material of choice. A symbol of femininity and a mark of the third eye—or ajna chakra—which connects the material to the spiritual, it is used by the artist as both a plastic and conceptual medium. Transformed into a fashion accessory subject to cultural appropriation in Bharti Kher’s work, it retains its power to activate surfaces: it questions how we see the world and reminds us that “the work also looks at us.” In its form of a spermatozoid-snake (a recurring animal in the artist’s bestiary), the bindi embodies the ambiguities between male virility and female fertility.

Depending on her works, the artist diffracts this infinitely plural symbolic charge of the bindi. Used in his famous monumental installations, such as The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own (2006) and An Absence of Assignable Cause (2007), it becomes a vibrant surface, a membrane and skin: an energetic threshold or portal connecting abstraction and narration. By aggregating thousands of them, the artist also questions their function as an indicator of sexual or national identity. On a cartographic scale, it acts as an arrow tracing migratory flows and the drifts of peoples. Thus, in the series Maps (2015) or in Not All Who Wander Are Lost (2015), bindis transform colonial maps into palimpsests inscribed with the shifting memory of borders and exiles. With this symbol, Kher reinvents a social and sensory abstraction, where each point contributes to shifting our perception, allowing us to become aware of dimensions that are often invisible but no less present.

Interior Landscapes

Seeing what usually escapes the eye is one of the major themes of Bharti Kher’s new series, Weather Painting, with which she returns to painting at a time of personal rebirth. These canvases are part of a meditation on both interior and exterior landscapes. The artist explores the idea that what happens in nature—cycles, forces, destruction, regeneration—is echoed in the intimate experience of the body and mind. The Weather Paintings thus show psychic, intimate, and abstract landscapes, traversed by storms, calm, or underground movements, where the pictorial space acts as a mirror of a state of flux and permanent change. This dimension echoes that of Indian cosmology, in which the world is produced by the feminine and dynamic energy of Shakti, goddess of vitality and transformation. The manifestation of this creative power is called Prakriti, the principle of living and diverse nature. Some paintings, such as Mother’s Fury (2023)—in which the voice of Mother Earth expresses her anger with the force of an uncontrollable and purifying element such as fire—seem to echo the ecofeminist warning of Vandana Shiva, for whom “the ecological crisis, at its root, is the death of the feminine principle.”

Some of these works take on a circular form reminiscent of both the bindi and a Petri dish: like magnifying glasses turned toward the infinitely small, these paintings evoke the cellular dimension of the body and the invisible microcosms revealed under the microscope, showing a space of inner transformations where the landscape becomes both cosmic and carnal. Their effectiveness stems from a fundamental gesture in Kher’s art: “Breaking what cannot be opened.” Tearing, splitting, and exposing invisible forces are both plastic and spiritual methods here—a means of revealing, through pictorial material, the invisible dynamics of what constitutes us.

Huile et pastel gras sur panneau / Oil and oil pastel on board. 6.12 × 10.12 pieds / ft. © Bharti Kher/ ADAGP, Paris 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Breaking and repairing

To detect what remains invisible in its original form, Bharti Kher also opens up the material itself: “I break things to know them,” she says. Her broken mirrors defy the superstitions attached to their shattering. Breaking the reflection is to break with the illusion of the unity of the body or the self, and reveal its multiplicity. In this act of breaking, Kher liberates the powers contained in the mirror, which ceases to be a mimetic tool and becomes a divinatory surface, open to possibilities. To the fault lines thus revealed, she patiently applies bindis, which, like colorful sutures, cover and hold the shards together, transforming the fracture into a new skin. Repairing is not about restoring lost unity, but inventing another body, traversed by the memory of its fractures. Kher’s mirrors thus become transitional surfaces where identity fragments, reassembles, and reinvents itself.

Like fractured mirrors, the Intermediaries proceed from a gesture of rupture followed by recomposition. Bharti Kher collects golus—clay figurines representing gods, animals, and humans, displayed in homes during the Navaratri festival—which she breaks and reassembles into hybrid creatures. Whether monumental bronze or recomposed statuette, each piece becomes a new avatar, born of the fracture. These sculptures act as mediators, passages where repair and metamorphosis merge.

Mythologies of the female body

Always engaged in a reinvention of mythology, Bharti Kher’s work has given rise to a feminine teratology, where the body becomes the privileged site of mutations and hybridizations. Her “mythical urban goddesses” are in turn ancestors, mothers, lovers, warriors, sex workers, or models, but also chimeras, half-human, half-animal. Inspired by Indian mythology and surrealism, Kher has revitalized the language of hybridity, investing it with political significance: making the female body an instrument of resistance to social and patriarchal norms. The photographic collages The Hybrid Series (2004), in which women and animals mingle with domestic objects, transform familiar spaces into a theater of metamorphosis. Machines, gods, flesh, and chimeras compose a repertoire of liminal figures, between the everyday and the marvelous, beauty and terror.

Like the bindi, Bharti Kher uses the sari as a material imbued with its own narrative. An emblematic garment of South Asia, passed down from mother to daughter and bearing the regional traditions of weaving, the sari condenses an intimate and collective memory. In the series Sari Women (since 2018), she freezes these supple fabrics in resin, draping them over silhouettes and exchanging their lightness for vitrified, almost mineral masses. This gesture transforms the garment into a monument, revealing its ritual and funerary dimension as well as its domestic heritage. Draped and solidified, the sari becomes a substitute for an absent or transfigured body. Between a tribute to female lineages and a diversion from the classic codes of draped statuary, Kher turns it into a plastic and symbolic medium where memory and spiritual transformations intertwine.

The technique of casting from real bodies occupies a central place in Bharti Kher’s work. The artist sees it as much more than a formal process: she casts bodies to capture their memories. Direct contact with the skin establishes a sensory intimacy where warmth, smells, folds, and pores become vectors of transmission. In this transition from skin to plaster, from living being to sculpture, an alchemical transubstantiation takes place: the body loses its individual identity and acquires a hybrid, almost mythical presence. Kher speaks of a practice of transfer, where the energies accumulated in a lifetime are imprinted in the material. Thus, the casts of Six Women (2012-2014), made from female sex workers in Kolkata, freeze real bodies—neither idealized nor sexualized, aging and marked by their experiences—while giving the figures another skin, another life.

After a long period of creating urban goddesses, Kher created her first papier-mâché sculpture, The Alchemist (2024), which presents itself as a kind of self-portrait. This female figure, framed by an upward-pointing triangle (the alchemical symbol of the masculine), plays the role of a shaman or mistress of ceremonies, capable of orchestrating the synergies of exhibition spaces. The artist emphasizes this dimension of animation: her works are imbued with personality, subjectivity, and agency. The Alchemist thus embodies the artist’s very gesture, that ritual of faith in which the energy invested in matter is transformed into an active presence capable of balancing opposites.

Argile, résine, cuivre, bois, cire / Clay, resin, copper, wood, wax, 141 × 29 × 29 cm (piédestal inclus) | 55 1/2 × 11 7/16 × 11 7/16 in (including pedestal). Photo : Kei Okano. © Bharti Kher/ ADAGP, Paris 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Questions of balance

In her abstract sculptures, Bharti Kher brings into play a “poetics of opposites” in which each element finds its center of gravity in a state of fragile tension. Works such as East of the Sun and West of the Moon (2015-2023) and A Frailty of Heart (2017) are based on a meticulous search for equal and opposite forces, where positive and negative, order and chaos, construction and destruction neutralize each other in unlikely but graceful configurations. The objects seem close to falling, but hold together, as if held in a kind of magical suspension. For Kher, this plastic research reflects a deeply physical experience: “Each sculpture has a tipping point, as if it were about to collapse, but my job is to balance its energies in order to hold it back.” Here, the creative gesture echoes the human condition itself, in a state of constant readjustment. Like the body, which constantly regulates its own internal balance to navigate the world, these sculptures embody a quest for equilibrium in which the materials seem to act beyond what they would normally accomplish.

Whether molded or veiled, seen from the inside or the outside, fragmented or absent, the body remains the center of gravity in Bharti Kher’s works. This diversity of approaches raises a Spinozist question: “What can a body do?” The artist tirelessly explores its magical, sensory, and emotional potential. For Kher, magic does not reside in esoteric doctrines, but in the very depth of bodies, in the energy of their experiences and the sensitivity they convey. Looking at her works therefore means mobilizing one’s entire being, feeling viscerally rather than understanding conceptually. By experiencing her works in this way, we perceive that they offer an interpretation of art as a philosophical practice: not a space where definitive answers are given, but a place where the right questions are asked.

Huile et pastel à l’huile sur placage de teck sur planche / Oil and oil pastel on teak veneer over board,

Ø: 6 pieds / ft. Photo : Tanguy Beurdeley. © Bharti Kher/ ADAGP, Paris 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

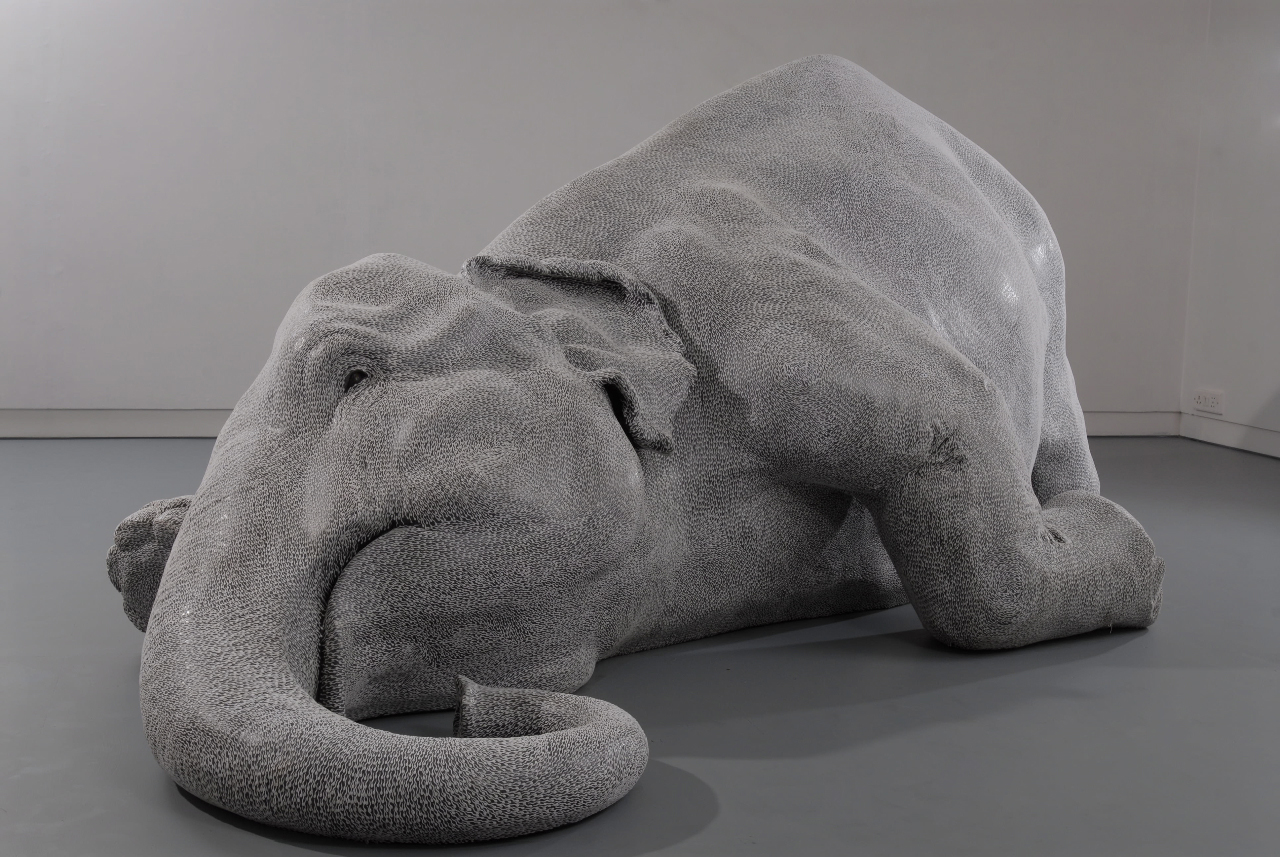

Head image : Bharti Kher, The skin speaks a language not its own, 2006. Fibre de verre, bindis / Fiberglass, bindis, 142 × 456 × 195 cm.

© Bharti Kher/ ADAGP, Paris 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Agnieszka Kurant , Tschabalala Self, Shio Kusaka, Jeanne Vicerial,

Related articles

Lucas Arruda

by Vanessa Morisset

Biennale Son

by Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

by Vanessa Morisset