After the End. Maps for Another Future

After the End. Maps for Another Future

Curated by Manuel Borja-Villel

Centre Pompidou-Metz

Until 1 September

Manuel Borja-Villel, former director of the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, presents a shifting constellation, an archipelago of artistic thoughts and gestures that challenge the linearity of Western history, in the exhibition After the End. Maps for Another Future at the Centre Pompidou-Metz. Bringing together some forty artists, it tackles the colonial legacy that still permeates our imaginations, our museums and our conceptions of time. A veritable living cartography, it invites us to navigate diasporic narratives, buried memories and possible futures, where modernity cracks open to reveal other worlds.

Here, there is no imposed route, no rigid chronology or thematic chapters. The exhibition ‘is established by relationships and affinities’[1] rather than by a well-ordered succession. This archipelagic structure, inspired by the works of Édouard Glissant and Gloria Anzaldúa, breaks with the Western perception of linear time that dictates history and marginalises non-hegemonic narratives. Instead, it proposes a circular, spiral-shaped time in which past, present and future intertwine. This temporal break is embodied in the diversity of the works on display, which span five centuries, engaging in dialogue through echoes, friction and silences, from the mixed-media ‘enconchados[2]’ by Juan and Miguel González to the incisive photographs of Ahlam Shibli, from the enigmatic collages of Belkis Ayón to the video ‘Teide’ by the Tizintizwa collective[3], which exhumes the massacre of the Canarian populations at the end of the 15th century. Together, these artistic gestures weave a web in which colonial wounds, whether Caribbean, Mediterranean or Palestinian, resonate with the same poetic and political urgency.

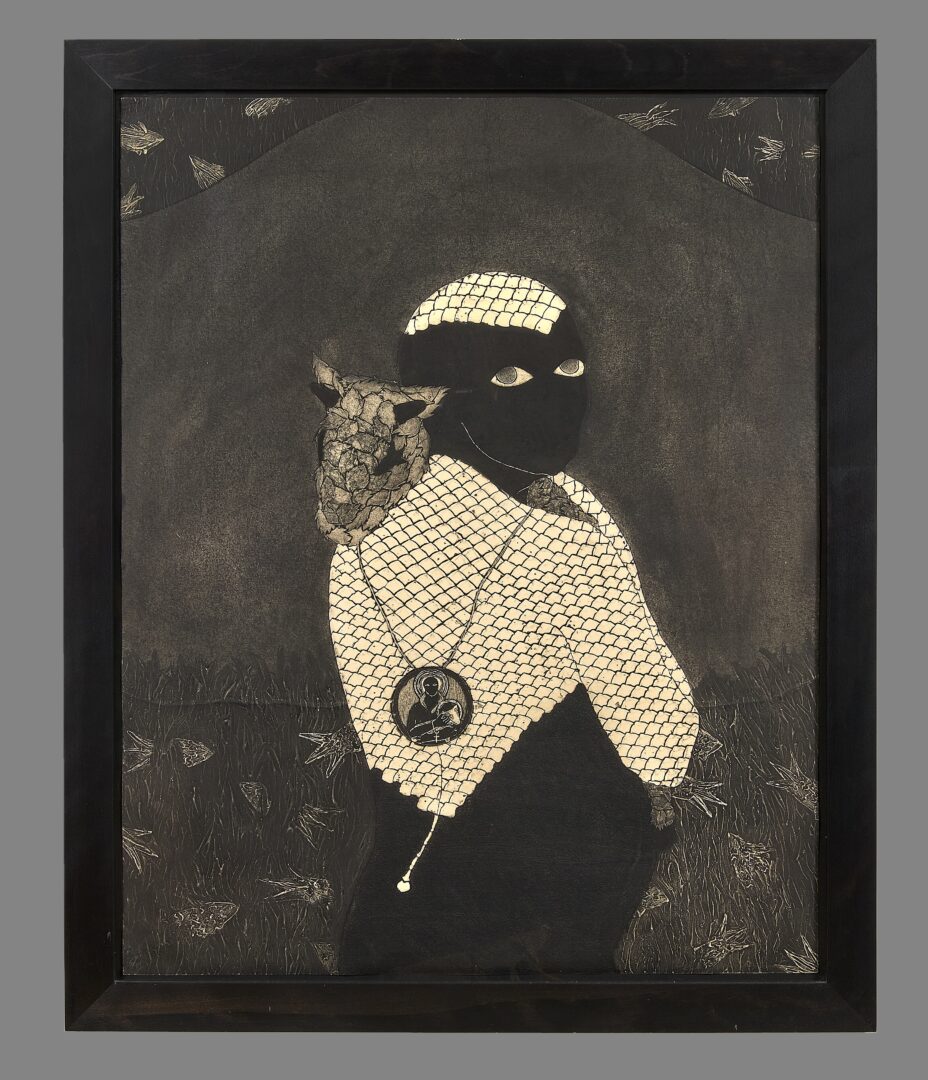

‘After the End’ is an attempt to ‘disenchant the established,’ to deconstruct the Western narrative rooted in a colonial system that imposed its categories, boundaries, and hierarchies. The exhibition questions and challenges. The works raise only open questions, ‘forms of radical imagination’ that sketch out worlds beyond the ‘epistemic closure’ of Western modernity. This decolonial ambition is manifested in the centrality given to the Caribbean and Mediterranean diasporas, territories of encounters and cross-fertilisation, but also of founding violence. Belkis Ayón’s collographs[4] impose themselves with magnetic force. Originating from the Cuban secret society Abakuà, reserved for men, these masked, mouthless figures stare at the visitor with a gaze that is both disturbing and accusatory. Their darkness, both aesthetic and symbolic, embodies the struggle against the invisibility of women and patriarchy, while carrying the memory of an African diaspora torn from its roots. Ahlam Shibli’s photographs, documenting Palestinian dispossession in al-Khalil/Hebron, resonate as a contemporary echo of these traumas, highlighting the persistence of colonial logic in our present. The exhibition brilliantly weaves together these secret correspondences between eras and geographies, as in the paintings of Wifredo Lam, which dialogue with Rubem Valentim’s sculptures from the ‘Templo de Oxala’, which fuse African deities and abstract modernity. The video of the Zapatista ‘March of Silence’ (2012), with its spiral evoking non-linear governance, responds to Yto Barrada’s images, which capture the experience of transit in Tangier, a border town between Africa and Europe. Through their formal diversity, these works draw an alternative cartography in which the margins become the centre and silenced voices speak out.

Borders – geographical, temporal, cultural – are here spaces of creation rather than separation, exploring what Gloria Anzaldúa calls ‘belonging without belonging[5]’, that diasporic condition of “being on the border .” Whether they come from the Caribbean, the Maghreb or the Levant, the artists convey this tension between uprooting and anchoring, between violence and resilience. Ellen Gallagher’s drawings, with their aquatic and organic motifs, evoke the depths of the Atlantic, a place of passage and loss for millions of slaves, which has become a space of ‘underground’ memory in which invisible narratives resurface, notes Olivier Marbœuf. This poetics of borders is also embodied in the scenography, which invites visitors to wander freely, almost organically. Arranged without hierarchy, the works create constellations within which each one can be a starting point or a stopover. This absence of an imposed route reflects the exhibition’s ambition to decolonise not only narratives, but also ways of looking, moving and thinking. Freed from their usual reference points, visitors become explorers of this archipelago, co-authors of the meanings that emerge from encounters between the works.

‘After the End’ is not a comforting exhibition. It does not promise immediate solutions or easy reconciliations. On the contrary, it confronts us with the structural violence of colonialism and its echoes in today’s ecological, migratory and social crises, but it is not without hope, drawing on ‘marginalised philosophies and spiritualities’ to imagine a united earth without fragmented borders. This hope is not naïve; it is rooted in the power of artistic gestures, in their ability to ward off trauma by inventing new forms and new narratives. The exhibition draws its strength from this tension between denunciation and imagination. Ahlam Shibli’s photographs, with their clinical precision, document oppression with blood-curdling acuity, while Kapwani Kiwanga’s banners, vibrant with colour and symbols, celebrate Haitian resistance and its ability to transform pain into spiritual power. Between wound and healing, between memory and becoming, the exhibition becomes a space for reflection as much as an act of collective creation. ‘After the End’ is a world-work, an artistic and political manifesto that challenges Western certainties. Drawing on artists as diverse as Aline Motta, Bouchra Ouizgen and Tizintizwa, the exhibition goes beyond criticism of the colonial past to venture into mapping possible futures, inviting us to rethink our relationship to time, space and others.

[1] Manuel Borja-Villel in his statement of intent.

[2] A popular Baroque art technique in 17th-century New Spain (colonial Mexico), which consists of inserting mother-of-pearl into paintings to create a luminous, iridescent effect.

[3] Nadir Bouhmouch & Soumeya Ait Ahmed.

[4] Guillaume Lasserre, ‘Belkis Ayon au-delà du mythe’ (Belkis Ayon beyond the myth), Un certain regard sur la culture/ Le Club de Mediapart, 9 April 2022, https://blogs.mediapart.fr/guillaume-lasserre/blog/080422/belkis-ayon-au-dela-du-mythe

[5] Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: the New Mestiza, Aunt Lute Books, San Francisco, 1987, 260 p., see also Maya Mihindou, ‘La Nouvelle Métisse: Paroles de Gloria Anzaldúa’ (The New Mestiza: Words of Gloria Anzaldúa), Ballast, 9(1), 2020, pp. 142-155.

Head image : Abdessamad EL MONTASSIR, Al Amakine [Les lieux], 5 caissons lumineux, paysages recto-verso de 108 x 72 x 12 cm, 5 caissons plantes recto-verso de 54 x 81 x 12 cm, installation sonore. Collection de l’artiste. Crédit Photo : Pierre Gondard © Adagp, Paris, 2024

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Camille Llobet, Wolfgang Tillmans, Bergen Assembly, Aline Bouvy, Candice Breitz,

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Thomias Radin

by Caroline Ferreira