« If I can’t dance to it, it’s not my revolution » au Haverford College, Pennsylvanie

Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, Pennsylvania. USA,

du 21 Mars au 2 Mai 2014.

Différentes factions engagées sous différents principes ; des manifestes passionnés qui déclenchent de grandes querelles et le soupçon d’un autoritarisme quelquefois terni par des alliances avec des gouvernements et des sociétés.

Dans une certaine mesure, l’histoire de l’anarchie ressemble à l’histoire de l’avant-garde artistique. Qu’est-ce qui, alors, empêche de catégoriser tout art comme anarchiste ? Dans if I can’t dance to it, it’s not my revolution, la curatrice Natalie Musteata propose « l’horizontalité », « le noir » et « l’amour libre » comme axes pour analyser les relations entre l’anarchie et l’art produit par vingt-sept artistes et collectifs dont l’œuvre s’étend des années soixante à nos jours.

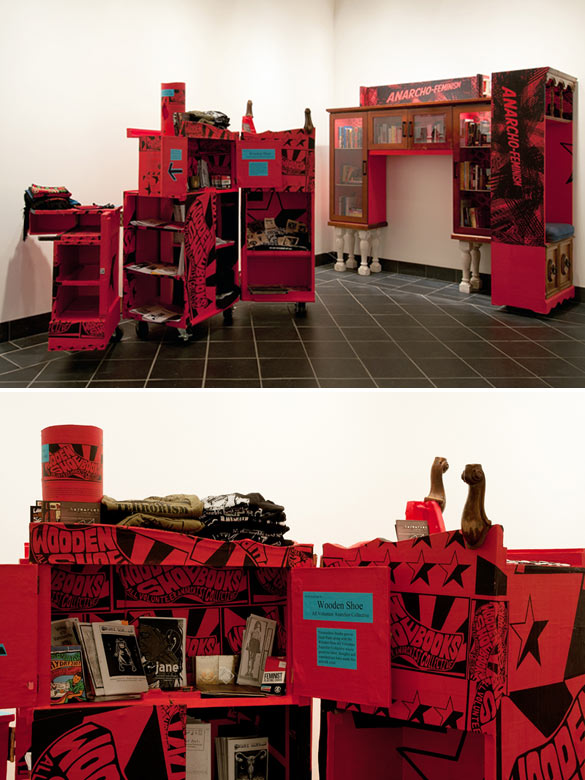

Certain thèmes sont bien définis dans l’espace tandis que d’autres émergent au hasard de l’exposition. Transformer Display for Community Education, Activism and Fundraising: Version 5 (2014) d’Andrea Bowers et Olga Koumoundouros incarne le principe d’horizontalité. Le projet, qui prend la forme de trois kiosques, est une collaboration entre les artistes et la librairie anarchiste de Philadephie, The Wooden Shoe. Chaque kiosque offre différents services. Le premier est situé juste devant la salle d’exposition principale et sert de salle de lecture ; le deuxième est une bibliothèque anarcho-féministe où les visiteurs sont incités à emprunter des livres à aller feuilleter sur Circles describing spheres (2013), la sculpture d’Adrian Blackwell toute proche ; le troisième vend des badges, des affiches et autres banderoles anarchistes.

Andrea Bowers and Olga Koumoundouros, « Transformer Display for Community Education, Activism and Fundraising » © photos Lisa Boughter.

Tandis que les principes horizontaux tels que l’organisation non-hiérarchique, la prise de décision collective et l’usage démocratique des matériaux caractérise le travail d’un certain nombre d’artistes de l’exposition, le concept de noirceur apparaît de manière plus restreinte. Le noir est à la fois la couleur officielle de l’anarchie et l’appellation raciale de nombreux activistes qui ont utilisé les tactiques anarchistes dans le Mouvement des droits civiques. Cette catégorie regroupe les œuvres les plus occupées à proposer de nouvelles connections entre l’anarchie et l’art comme vecteur de changement social. Par exemple, les impressions sur papier journal de Gayle “Asali” Dickson sont de puissants témoignages des mauvais traitements infligés aux femmes afro-américaines. Elles ont régulièrement été publiées dans journal du Black Panther Party mais ont depuis été oubliées. Sur un tract politique réalisé à l’occasion des élections municipales à Oakland (Californie) en 1972, l’on peut voir une femme, bigoudis sur la tête, se détacher sur un fond jaune qui en intensifie les traits, tandis qu’au-dessus d’un photo-montage de gens qui semblent la suivre résonnent les mots : « Survival, survival, survival! ». L’on retrouve le ton militant de l’œuvre de Dickson dans les journaux publiés par le collectif anarchiste Black Mask (1965-68) et dans les séquences palpitantes d’émeutes raciales, de manifestations et d’assassinats rassemblées dans le film d’Aldo Tambellini Black TV (1968).

Black Mask, various broadsheets and publications / Gayle « Asali » Dickson, numerous prints © photos Lisa Boughter.

Si la catégorie « noir » rassemble un grand nombre d’artistes méconnus, « l’amour libre », au contraire, en réunit de plus connus. Meat Joy (1964-2010), le film de Carolee Schneemann, exhale l’anarchie sous forme d’entrailles de poissons, de membres agités et de cous de poulets brisés. Sur le même mur, sont projetées deux autres œuvres vidéo du collectif danois Kanonklubben et, en face, des films de Sherry Millner et Ernest Larsen sont présentés sur moniteur. Aucun ne peut bien sûr égaler l’extrême exubérance de l’ode orgiaque de Schneemann.

Les tas de viande dans Meat Joy et les abstractions brouillées de Black TV sont un véritable antidote au début trop textuel de l’exposition. En effet, l’œuvre résolument littéraire qui donne son cadre à l’exposition suggère que l’anarchie, paradoxalement, repose sur l’un des systèmes les plus structuré au monde : celui du langage. Un tel système pourra-t-il jamais rompre un ordre ancien ? Seuls John Cage et Jackson Mac Low explorent cette question de manière formelle. Cage et Mac Low ont utilisé le hasard pour ordonner le langage dans leurs poèmes. D’autres artistes présentés ici conservent au contraire les règles grammaticales pour transmettre un contenu révolutionnaire. Une telle accumulation de choses à lire au début d’une exposition postule des prérequis : l’anarchie requiert des lectures, des méthologies à maîtriser, et des manuels pour initiés. De ce fait, l’exposition est tout à fait à sa place dans la galerie d’une institution universitaire tel que le Haverford College.

Est-ce une contradiction ? Peut-être. Mais, ainsi que The Wooden Shoe le déclare dans l’énoncé de sa mission, nous fonctionnons tous « à l’intérieur d’un système auquel nous nous opposons » quand nous prenons la peine de le faire. Ce qui est intéressant dans la conception de Musteata, c’est son désir d’avoir une opinion politique à identifier et à discuter. Que cela nous mène à penser notre place au sein des structures de pouvoir est une bonne chose, même si cela signifie nécessairement la prolifération des contradictions et que les images simples cèderont sous la pression des politiques réelles.

Various factions committed to various principles; passionate manifestos sparking bitter quarrels; and a suspicion of authoritarianism occasionally tarnished by alliances with governments, corporations, or other entities of power. To some extent, the history of anarchy reads like the history of the artistic avant-garde. What, then, prevents all art from being categorized as anarchist? In, if I can’t dance to it, it’s not my revolution curator Natalie Musteata suggests Horizontality, Black, and Free Love as lenses to focus the relationship between anarchy and the art of 27 artists and collectives whose work spans 1960 to the present.

Certain of these themes are spatially delineated while others surface randomly throughout the show. Andrea Bowers and Olga Koumoundouros’ Transformer Display for Community Education, Activism and Fundraising: Version 5 (2014) embodies the principle of horizontality. The project—in the form of three different kiosks— is a collaboration between the artists and Philadelphia-based anarchist bookstore, The Wooden Shoe. Each kiosk offers different services. The first sits directly outside the main gallery and functions as a ‘take a book/leave a book’ reading room; the second is an anarcha-feminist library, where visitors are encouraged to borrow books to peruse on Adrian Blackwell’s adjacent sculpture-cum-public-bench, Circles describing spheres (2013); the third sells patches, posters, and other anarchist swag.

While horizontal principles such as non-hierarchical organization, collective decision-making, and the democratic use of materials characterize the work of many artists in the show, the concept of Blackness is more restricted. Black is both the official color of anarchy and the racial designation of many activists who used anarchist tactics in the Civil Rights movement. This category works hardest to forge new connections between anarchy and art as an agent for social change. For example, Gayle “Asali” Dickson’s prints are powerful indictments of the mistreatment of African American women. They appeared regularly in the Black Panther Party’s newspaper but have since been forgotten. One political campaign endorsement for a race in Oakland, California, in 1972 features a woman in curlers, dramatically outlined against a yellow ground. A line of photo-montaged people stream behind her while the motto, “Survival, survival, survival!” rings out above her head. The militant tone of Dickson’s work is echoed in the broadsheets published by the based anarchist collective, Black Mask (1965-68), and by the pulsating footage from race riots, demonstrations, and assassinations spliced together in Aldo Tambellini’s film Black TV (1968).

If the category, ‘Black,’ yields the largest number of under-recognized artists then ‘Free Love,’ delivers one of the most familiar standbys. Carolee Schneemann’s film, Meat Joy (1964-2010) oozes anarchy in the form of fish guts, flapping limbs, and snapping chicken necks. The film shares a wall with two other moving image works by the Danish film collective Kanonklubben and faces off with a monitor screening films by Sherry Millner and Ernest Larsen on the opposite wall. Neither can match the sheer exuberance of Schneemann’s orgiastic ode.

Carolee Schneemann’s « Meat Joy » © photos Lisa Boughter.

The piles of flesh in Meat Joy and the blurred abstractions in Black TV provide a antidote to the text-heavy start of the exhibition. Indeed, the decidedly literary work that frames the show suggests that anarchy—paradoxically—relies on one of the most highly structured systems in the world: that of language. Can such a system ever rupture an old order? Of all the tomes, broadsheets, posters, and flyers that populate the atrium and the first few galleries, only the poems by John Cage and Jackson Mac Low explore this question at the level of form. Cage and Mac Low used chance operations to randomly order language. Other artists on view maintain grammatical rules in order to transmit revolutionary content. Such an accumulation of reading materials at the beginning of the exhibition posits pre-requisites: anarchy has required readings, methodologies to master, and handbooks for the initiated. In this way, the show is very much at home in the gallery of an academic institution such as Haverford College.

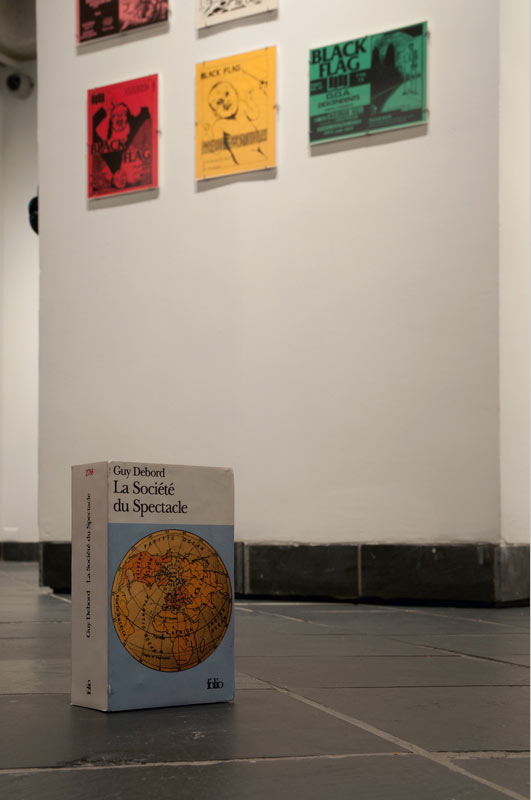

Claire Fontaine, « La société du spectacle » © photos Lisa Boughter.

Is that a contradiction? Maybe. But as The Wooden Shoe acknowledges in its mission statement, we all function “within a system we oppose” whenever we bother to struggle. The exhibition may begin with textual didacticism but it ultimately dissolves into visual abstraction. Bowers and Koumoundouros’ well-lit reading room cedes to a darkened theater; moments of mute static in Tambellini’s film stymie even the most emphatic prescriptions from the preceding posters. Lest I conclude by suggesting some final opposition between form and content in the anarchist aesthetic, let me turn to an artwork that is also an action. Claire Fontaine’s La société du spectacle brickbat (2005) intervenes between text and object with stunning dialectical swiftness. Resting on the floor sits what appears to be a copy of Guy Debord’s foundational Situationist text. In reality, the pages have been replaced by a red clay brick, the cover, by a modified sleeve. Here, content meets form in an object that turns a text into a projectile. The instrumentalized Debord is at once a facile joke and a blunt weapon. It may work better like this, but it could never have worked at all had not the careful labor of theory preceded it.

What I like about Musteata’s vision is the desire to have a politics, to discuss and debate and identify. That we should think about our place in structures of power is a good thing, even if it necessarily means that contradictions proliferate and that simple pictures buckle under the pressure of real politics.

articles liés

Leonor Serrano Rivas

par Mya Finbow

Flux de nos yeux

par Gabriela Anco

Electric Op

par Sandra Doublet