Guy de Cointet

M Museum, Leuven, September 17 2015 to January 10 2016

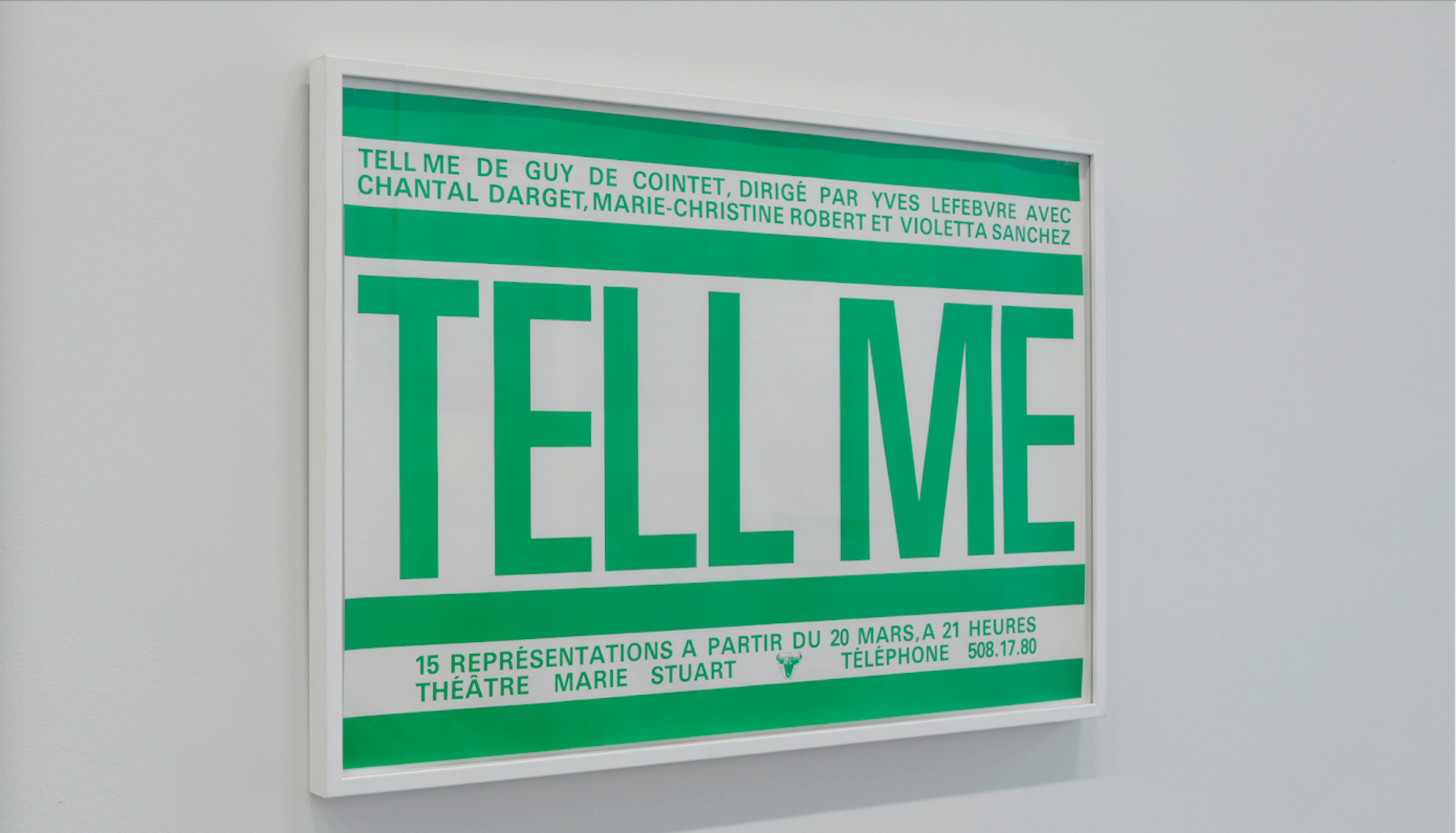

People tend to be acquainted with Guy de Cointet’s performances, which have been the subject of many reenactments since his death in 1983, in particular the famous Tell Me of 1979, whose set, with all the props/sculptures, is on view in this exhibition, and was used as a framework for the reading of a text by the artist (Esphador Ledet Ko Uluner!,1973—2015 interpretation) at the Playground Festival.1 When she was the festival’s director, Eva Wittocx had scheduled many pieces by the Franco-American artist, before being appointed to the M Museum, where she was then in a position to organize this sort of retrospective. De Cointet was intrigued by the status of language and the ways it appeared—even though he was not really a linguistic theoretician but rather a French emigrant immersed in the very cosmopolitan city of Los Angeles, in the midst of a population speaking every possible language. Anecdote has it that he hung not so much on the words of his new compatriots as on their body language, trying to guess the meaning of exchanges through vocal intonations and arm movements rather than through words which he could not understand. Was he perhaps a forerunner of non-verbal communication? In one sense, yes, because what emerges from his performances is the discrepancy between the meaning of the words exchanged in the short scenes and the actors’ actions on the set (actresses in the case of Tell Me), a discrepancy underscoring the “gestural discourse” in the intellection process, rather than the statements. So his performances have the merit of making these phenomena much more “eloquent” than lengthy linguistic digressions.

Needless to say, it is also the significance of objects which is still powerfully addressing a whole generation of young artists, because, with de Cointet, the status of the object is quintessential, evolving somewhere between the “role” of prop for the performances and the role of sculpture with variable dimensions. These objects/sculptures have their place in a process of global signification, like a kind of syntagm in the middle of a sentence, before returning to their status of inert object, once de-activated.

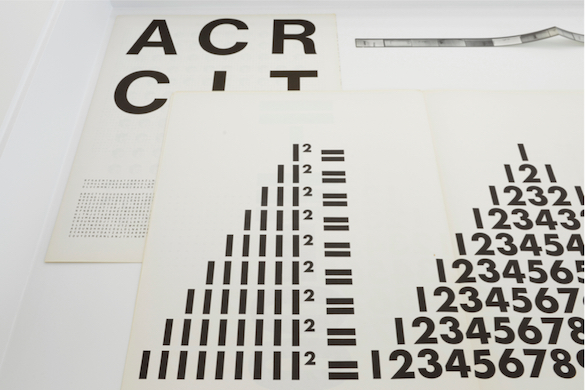

Guy de Cointet, ACRCIT, 1971. Courtesy Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Musée national d’art moderne, Centre de création industrielle. Photo : Isabelle Arthuis.

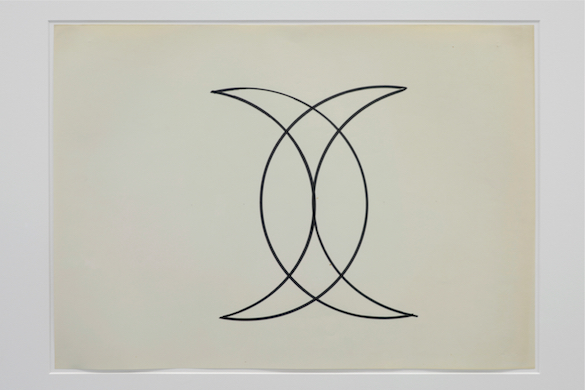

The show at the M Museum enables us to plunge into the genesis of the work of an artist who embarked on his professional life in an advertising agency: the posters produced for the première of Tell Me, and above all the one designed for the spectacle Ethiopia (1976), illustrate his elegance and his mastery of graphic codes. So it is perhaps no coincidence that he was so keenly interested in the function of language and its inner codifications, the fact remaining that he took a very close look at the relations between the form of alphabetical symbols and the aesthetics of writing, which he did his utmost to explore in every direction. Relying on numerous loans from the Centre Pompidou and Les Abattoirs Museum in Toulouse, the exhibition sheds light on the scope of a body of work capable of inventing coding systems worthy of the world of espionage—which must definitely have fascinated him2—while at the same time being capable of “juggling” with numbers and making them produce thoroughly bewildering “totals”. De Cointet did not stop at busily inventorying the combinational possibilities of “alphabetical” writing (also having fun writing with both hands, like any self-respecting, frustrated, left-handed person becoming ambidextrous); he also emphasized the pure aesthetic aspect of this latter, as in the picture Sans titre (1971), where he aligned four columns of excerpts from texts ranging from a medical handbook to a page from a novel. He was also capable of playing indefinitely with fonts of characters which he stretched to the limit of recognition, in an extreme stylization which removed the maximum amount of their “matter” from symbols, comparing them to the Morse alphabet—the most abstract of all—which also greatly fascinated him. It was when he mixed his unravelled writing with small minimal signs, lozenges, squares and rectangles interspersed along or prolonging the line of writing, and causing the meaning of the writings to veer off towards an abstract composition, that de Cointet’s drawings acquired all the power of their delicate affectedness. As far as numbers are concerned, they are not absent from his investigations, being the subject of special treatments, little arithmetical games drifting towards “drawings” that are as simple as they are exhilarating, like these enigmatic columns of numbers and these “magic” additions which produce perfectly aligned series of ‘1’s, an unlikely mixture of the aesthetic and the mathematical. The same goes for this extraordinary “signature of Mahomet”, thus titled by the artist, which surveys the entrance to the show, obviously paying tribute to the Arab civilization—which created the word “cipher” and busily produced graphic and calligraphic abstractions—made up of two intertwined half-moons which we are meant to be able to draw in a single stroke… The show’s organizers had the bright idea, what is more, of re-printing the famous ACRCIT, an outsized publication and nothing less than a “Rosetta stone” of his projects, as he was fond of calling it, which brings together all the artist’s systemic inventions, from his pages of mirror writings to his pyramids of letters lined up in enigmatic arrangements, by way of crosswords and the Morse alphabet, once and for all finding a place for this artist, who defies pigeonholing, on the shores of a playful and prolific esotericism.

Guy de Cointet, Sans Titre (Signature de Mahomet), ca 1971. Courtesy Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Musée national d’art moderne, Centre de création industrielle. Photo : Isabelle Arthuis

1 Playground is one of Europe’s major performance festivals. It is held every year in November at the STUK in Leuven, an art centre dedicated to dance, music and sound. (http://www.stuk.be/en/house-dance-image-and-sound).

2 De Cointet’s very discreet private life gave rise to many rumours, including one that he belonged to the French secret service…

- From the issue: 80

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Lyon Biennial, Anozero' 24, Coimbra Biennal, Signs and Objects. Pop art from the Guggenheim Collection at Guggenheim Museum, Momentum 12 at Moss, Yayoi Kusama : 1945 to Now at Guggenheim Bilbao,

Related articles

Lyon Biennial

by Patrice Joly

Not Everything is Given, Whitney ISP, New York

by Warren Neidich

Rafaela Lopez at Forum Meyrin

by Guillaume Lasserre